4. Orikabe L, Yamasue H, Inoue H, Takayanagi Y, Mozue Y, Sudo Y, et al. Reduced amygdala and hippocampal volumes in patients with methamphetamine psychosis. Schizophr Res 2011;132:183-189.

7. Choi MR, Chun JW, Kwak SM, Bang SH, Jin YB, Lee Y, et al. Effects of acute and chronic methamphetamine administration on cynomolgus monkey hippocampus structure and cellular transcriptome. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2018;355:68-79.

8. Rahimi Borumand M, Motaghinejad M, Motevalian M, Gholami M. Duloxetine by modulating the Akt/GSK3 signaling pathways has neuroprotective effects against methamphetamine-induced neurodegeneration and cognition impairment in rats. Iran J Med Sci 2019;44:146-154.

9. Zimmerman JL. Cocaine intoxication. Crit Care Clin 2012;28:517-526.

10. Castilla-Ortega E, Serrano A, Blanco E, Araos P, Suárez J, Pavón FJ, et al. A place for the hippocampus in the cocaine addiction circuit: potential roles for adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;66:15-32.

14. Verdejo A, Toribio I, Orozco C, Puente KL, Pérez-García M. Neuropsychological functioning in methadone maintenance patients versus abstinent heroin abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2005;78:283-288.

15. Jiang Y, Yang W, Zhou Y, Ma L. Up-regulation of murine double minute clone 2 (MDM2) gene expression in rat brain after morphine, heroin, and cocaine administrations. Neurosci Lett 2003;352:216-220.

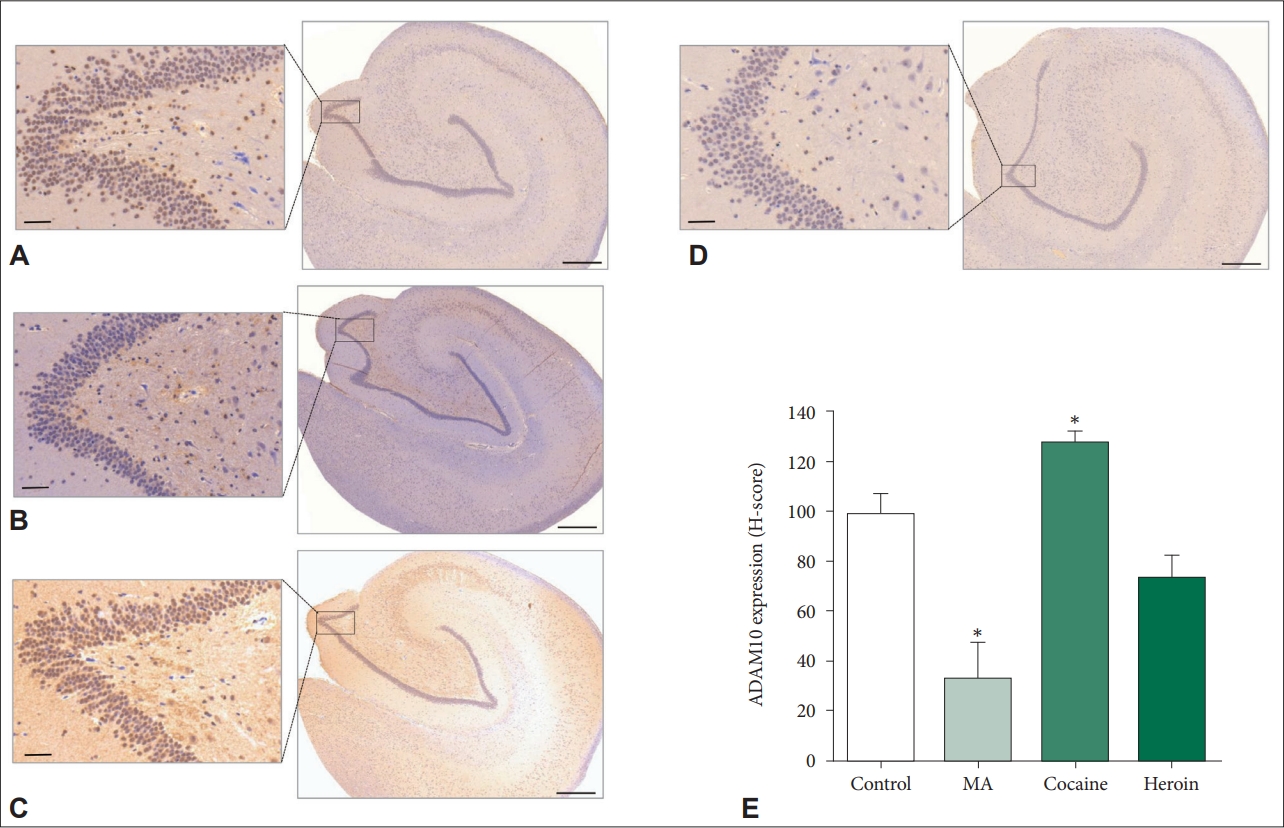

18. Paudel S, Kim YH, Huh MI, Kim SJ, Chang Y, Park YJ, et al. ADAM10 mediates N-cadherin ectodomain shedding during retinal ganglion cell differentiation in primary cultured retinal cells from the developing chick retina. J Cell Biochem 2013;114:942-954.

19. Saftig P, Lichtenthaler SF. The alpha secretase ADAM10: a metalloprotease with multiple functions in the brain. Prog Neurobiol 2015;135:1-20.

21. Lammich S, Kojro E, Postina R, Gilbert S, Pfeiffer R, Jasionowski M, et al. Constitutive and regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer’s amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999;96:3922-3927.

22. Yuan XZ, Sun S, Tan CC, Yu JT, Tan L. The role of ADAM10 in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;58:303-322.

23. Choi MR, Bang SH, Jin YB, Lee Y, Kim HN, Chang KT, et al. Effects of methamphetamine in the hippocampus of cynomolgus monkeys according to age. Biochip J 2017;11:272-285.

24. Kofler J, Lopresti B, Janssen C, Trichel AM, Masliah E, Finn OJ, et al. Preventive immunization of aged and juvenile non-human primates to β-amyloid. J Neuroinflammation 2012;9:84

26. Yeo HG, Lee Y, Jeon CY, Jeong KJ, Jin YB, Kang P, et al. Characterization of cerebral damage in a monkey model of Alzheimer’s disease induced by intracerebroventricular injection of streptozotocin. J Alzheimers Dis 2015;46:989-1005.

32. Soussi-Yanicostas N, de Castro F, Julliard AK, Perfettini I, Chédotal A, Petit C. Anosmin-1, defective in the X-linked form of Kallmann syndrome, promotes axonal branch formation from olfactory bulb output neurons. Cell 2002;109:217-228.

33. Dodé C, Hardelin JP. Clinical genetics of Kallmann syndrome. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2010;71:149-157.

36. Suhara T, Magrané J, Rosen K, Christensen R, Kim HS, Zheng B, et al. Abeta42 generation is toxic to endothelial cells and inhibits eNOS function through an Akt/GSK-3beta signaling-dependent mechanism. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24:437-451.

38. Wang WC, Cheng CF, Tsaur ML. Immunohistochemical localization of DPP10 in rat brain supports the existence of a Kv4/KChIP/DPPL ternary complex in neurons. J Comp Neurol 2015;523:608-628.

42. Horng JL, Lin LY, Huang CJ, Katoh F, Kaneko T, Hwang PP. Knockdown of V-ATPase subunit A (atp6v1a) impairs acid secretion and ion balance in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007;292:R2068-R2076.

45. Murase S, Schuman EM. The role of cell adhesion molecules in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr Opin Cell Biol 1999;11:549-553.

49. Gao C, Chen YG. Dishevelled: the hub of Wnt signaling. Cell Signal 2010;22:717-727.

52. Alimohamad H, Sutton L, Mouyal J, Rajakumar N, Rushlow WJ. The effects of antipsychotics on beta-catenin, glycogen synthase kinase-3 and dishevelled in the ventral midbrain of rats. J Neurochem 2005;95:513-525.

55. Yedavalli VS, Neuveut C, Chi YH, Kleiman L, Jeang KT. Requirement of DDX3 DEAD box RNA helicase for HIV-1 Rev-RRE export function. Cell 2004;119:381-392.

60. Martin SJ, Grimwood PD, Morris RG. Synaptic plasticity and memory: an evaluation of the hypothesis. Annu Rev Neurosci 2000;23:649-711.

62. Thompson AM, Gosnell BA, Wagner JJ. Enhancement of long-term potentiation in the rat hippocampus following cocaine exposure. Neuropharmacology 2002;42:1039-1042.

63. Ishikawa A, Kadota T, Kadota K, Matsumura H, Nakamura S. Essential role of D1 but not D2 receptors in methamphetamine-induced impairment of long-term potentiation in hippocampal-prefrontal cortex pathway. Eur J Neurosci 2005;22:1713-1719.

66. Hartmann D, de Strooper B, Serneels L, Craessaerts K, Herreman A, Annaert W, et al. The disintegrin/metalloprotease ADAM 10 is essential for Notch signalling but not for alpha-secretase activity in fibroblasts. Hum Mol Genet 2002;11:2615-2624.

67. Shukla M, Maitra S, Hernandez JF, Govitrapong P, Vincent B. Methamphetamine regulates βAPP processing in human neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci Lett 2019;701:20-25.