1. Association Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edition. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1997.

2. Mataix-Cols D, Rauch SL, Baer L, Eisen JL, Shera DM, Goodman WK, et al. Symptom stability in adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: data from a naturalistic two-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:263-268. PMID:

11823269.

3. Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Tolin DF. Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:572-581. PMID:

17343963.

4. Foa EB. Cognitive behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2010;12:199-207. PMID:

20623924.

5. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Core Interventions in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Body Dysmorphic Disorder. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; 2005.

6. Blanco C, Olfson M, Stein DJ, Simpson HB, Gameroff MJ, Narrow WH. Treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder by U.S. psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:946-951. PMID:

16848654.

7. Torres AR, Prince MJ, Bebbington PE, Bhugra DK, Brugha TS, Farrell M, et al. Treatment seeking by individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder from the british psychiatric morbidity survey of 2000. Psychiatr Serv 2007;58:977-982. PMID:

17602015.

8. Marques L, LeBlanc NJ, Weingarden HM, Timpano KR, Jenike M, Wilhelm S. Barriers to treatment and service utilization in an internet sample of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depress Anxiety 2010;27:470-475. PMID:

20455248.

9. Collins KA, Westra HA, Dozois DJ, Burns DD. Gaps in accessing treatment for anxiety and depression: challenges for the delivery of care. Clin Psychol Rev 2004;24:583-616. PMID:

15325746.

10. Mataix-Cols D, Marks IM. Self-help with minimal therapist contact for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. Eur Psychiatry 2006;21:75-80. PMID:

16360307.

11. Yang JC, Ha TH, Kim W, Kim SJ, Koo MS, Kwon JS, et al. Korean treatment algorithm for obsessive-compulsive disorder 2007 (III): a preliminary study for application of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Korean J Psychopharmacol 2007;18:408-413.

12. Moritz S, Jelinek L, Hauschildt M, Naber D. How to treat the untreated: effectiveness of a self-help metacognitive training program (myMCT) for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2010;12:209-220. PMID:

20623925.

13. Tolin DF, Diefenbach GJ, Gilliam CM. Stepped care versus standard cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a preliminary study of efficacy and costs. Depress Anxiety 2011;28:314-323. PMID:

21381157.

14. Clark A, Kirkby KC, Daniels BA, Marks IM. A pilot study of computer-aided vicarious exposure for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1998;32:268-275. PMID:

9588306.

15. Greist JH, Marks IM, Baer L, Kobak KA, Wenzel KW, Hirsch MJ, et al. Behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder guided by a computer or by a clinician compared with relaxation as a control. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:138-145. PMID:

11874215.

16. Lenhard F, Vigerland S, Andersson E, Ruck C, Mataix-Cols D, Thulin U, et al. Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e100773PMID:

24949622.

17. Wootton BM, Titov N, Dear BF, Spence J, Andrews G, Johnston L, et al. An internet administered treatment program for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a feasibility study. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25:1102-1107. PMID:

21899983.

18. Andersson E, Enander J, Andren P, Hedman E, Ljotsson B, Hursti T, et al. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med 2012;42:2193-2203. PMID:

22348650.

19. Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Mazure C, Fleischmann RL, Hill CL, et al. The Yale-Brown obsessive compulsive scale: I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1989;46:1006-1011. PMID:

2684084.

20. Kenwright M, Marks I, Graham C, Franses A, Mataix-Cols D. Brief scheduled phone support from a clinician to enhance computer-aided self-help for obsessive-compulsive disorder: randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychol 2005;61:1499-1508. PMID:

16173084.

21. Andersson E, Ljotsson B, Hedman E, Kaldo V, Paxling B, Andersson G, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder: a pilot study. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:125PMID:

21812991.

22. Gilliam CM, Diefenbach GJ, Whiting SE, Tolin DF. Stepped care for obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial. Behav Res Ther 2010;48:1144-1149. PMID:

20728075.

23. Cho MJ. The 2011 Epidemiological Survey of Mental Disorders among Korean Adults. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2011.

24. Keeley ML, Stroch EA, Merlo LJ, Geffken GR. Clinical predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 2008;28:118-130. PMID:

17531365.

25. Abramovitch A, Abramowitz JS, Mittelman A. The neuropsychology of adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2013;33:1163-1171. PMID:

24128603.

26. Cavedini P, Riboldi G, D'Annucci A, Belotti P, Cisima M, Bellodi L. Decision-making heterogeneity in obsessive-compulsive disorder: ventromedial prefrontal cortex function predicts different treatment outcomes. Neuropsychologia 2002;40:205-211. PMID:

11640942.

27. Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. User's Guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders [SCID-I]: Clinician Version. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

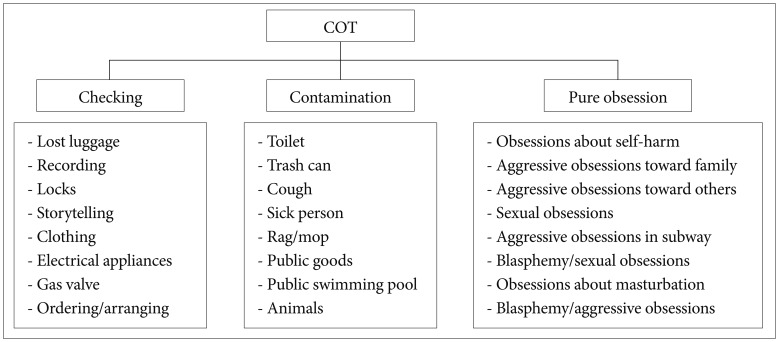

28. Shin MS, Seol SH. Cognitive-behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cogn Behav Ther Korea 2007;7:17-40.

29. Yoon HY, Jeong SH, Shin MS, Kim JS, Kim MS, Kwon JS. Group cognitive behavioral treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Korean J Psychopathol 2000;9:142-156.

30. Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Mastery of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: a Cognitive-Behavioral Approach Therapist Guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004.

31. Salkovskis PM, Kirk J. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. In: Clark DM, Fairburn CG, editor. Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 179-208.

33. Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1988;8:77-100.

34. Beck A, Steer R. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1993.

35. Mundt JC, Marks IM, Shear MK, Greist JH. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. Br J Psychiatry 2002;180:461-464. PMID:

11983645.

36. Olley A, Malhi G, Sachdev P. Memory and executive functioning in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a selective review. J Affect Disord 2007;104:15-23. PMID:

17442402.

37. Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Theory and Clinical Interpretation. Tucson: Neuropsychology Press; 1985.

38. Kim JK, Kang YW. Korean-California Verbal Learning Test. Seoul: The Psychological Company; 1997.

39. Kim HK. Rey-Kim Memory Test. Daegu: Korea Neuropsychology Press; 1999.

40. Kim HK. Kims Frontal-Executive Neuropsychological Test. Daegu: Korea Neuropsychology Press; 2001.

41. Freedman M, Black S, Ebert P, Binns M. Orbitofrontal function, object alternation and perseveration. Cereb Cortex 1998;8:18-27. PMID:

9510382.

42. Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: Computer Version 2. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1993.

43. Yum TH, Park YS, Oh KJ, Kim JG, Lee YH. The manual of Korean-Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Seoul: Korean Guidance Press; 1992.

44. Fisher PL, Wells A. How effective are cognitive and behavioral treatments for obsessive-compulsive disorder? A clinical significance analysis. Behav Res Ther 2005;43:1543-1558. PMID:

16239151.

45. Farris SG, McLean CP, Van Meter PE, Simpson HB, Foa EB. Treatment response, symptom remission, and wellness in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2013;74:685-690. PMID:

23945445.

46. Marks IM, Cavanagh K, Gega L. CP for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. In: Marks IM, Cavanagh K, Gega L, editor. Hands-on Help: Computer-Aided Psychotherapy. Hove and New York: Psychology Press, 2007, p. 61-72.

47. Steketee G, Barlow DH. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. In: Barlow DH, editor. Anxiety and its Disorders: the Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic. New York: The Guilford Press, 2004, p. 516-550.

48. Leyfer OT, Ruberg JL, Woodruff-Borden J. Examination of the utility of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and its factors as a screener for anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord 2006;20:444-458. PMID:

16005177.

49. Novara C, Pastore M, Ghisi M, Sica C, Sanavio E, McKay D. Longitudinal aspects of obsessive compulsive cognitions in a non-clinical sample: a five-year follow-up study. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2011;42:317-324. PMID:

21356173.

50. Han E, Cho Y, Park S, Kim H, Kim S. Factor structure of the Korean version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory: an application of confirmatory factor analysis in psychiatric patients. Korean J Clin Psychol 2003;22:261-270.

51. Lenhard F, Vigerland S, Andersson E, Rück C, Mataix-Cols D, Thulin U, et al. Internet-delivered cognitivie behavior therapy for adolescents with obsessive-copulsive disorder: an open trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e100773PMID:

24949622.

52. Simpson HB, Maher MJ, Wang Y, Bao Y, Foa EB, Franklin M. Patient adherence predicts outcome from cognitive behavioral therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:247-252. PMID:

21355639.

53. Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J Psychiatr Res 2013;47:33-41. PMID:

22999486.

54. Huppert JD, Franklin ME. Cognitive behavioral therapy for obsessivecompulsive disorder: an update. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2005;7:268-273. PMID:

16098280.

55. Mewton L, Sachdev PS, Andrews G. A naturalistic study of the acceptability and effectiveness of internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for psychiatric disorders in older australians. PLoS One 2013;8:e71825PMID:

23951253.

56. Moritz S, Kloss M, Jacobsen D, Fricke S, Carrie C, Brassen S, et al. Neurocognitive impairment does not predict treatment outcome in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther 2005;43:811-819. PMID:

15959930.

57. D'Alcante CC, Diniz JB, Fossaluza V, Batistuzzo MC, Lopes AC, Shavitt RG, et al. Neuropsychological predictors of response to randomized treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2012;39:310-317. PMID:

22789662.