Pandemic Grief Reaction and Intolerance of Uncertainty on the Cognitive-Behavioral Model of COVID-Related Hypochondriasis Among Firefighters

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to explore the feasibility of cognitive-behavioral model hypochondriasis regarding coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) among firefighters. In addition, we examined the possible role of their grief reaction and intolerance of uncertainty in the model of COVID-related hypochondriasis.

Methods

An anonymous online survey was done on October 27–28, 2022, among firefighters who witnessed people’s death. Demographic characteristics were collected, and their psychological states were assessed using rating scales such as the Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS), Coronavirus Reassurance-Seeking Behaviors Scale (CRBS), Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S), Pandemic Grief Scale (PGS), and Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale–12 (IUS-12).

Results

Their OCS score was expected by the CRBS (β=0.30, p<0.001), FCV-19S (β=0.10, p<0.001), PGS (β=0.29, p<0.001), and IUS-12 (β=0.04, p=0.024) (F=134.5, p<0.001). The COVID-related cognitive-behavioral model of hypochondriasis was feasible among firefighters who witnessed people’s death. Their pandemic grief reaction and intolerance of uncertainty directly influenced their preoccupation with coronavirus, and viral anxiety and coronavirus reassurance-seeking behavior mediated the relationship.

Conclusion

Firefighters’ viral anxiety and coronavirus reassurance-seeking behavior mediated the influence of pandemic grief reaction or intolerance of uncertainty on the preoccupation with coronavirus.

INTRODUCTION

During the pandemic, firefighters play an important role in protecting the community and responding to various emergencies. Simultaneously, they were among the groups most affected by the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic [1,2]. Since firefighters are responsible for transporting suspected COVID-19 patients, they have made great efforts to prevent the spread of the disease. They were required to wear Level D protective clothing, overshoes, gloves, N95 masks, and goggles as part of their protective equipment [3]. Following the transfer of the patient, disinfection was required, and the firefighters who took part in the transfer would be quarantined in their facility if COVID-19 was confirmed. As a result of the overcrowding of hospital isolation facilities and emergency rooms during the pandemic, patients had to travel further to reach the available facilities. The number of firefighters infected or quarantined has increased in recent years, which has resulted in them having to work on holidays or repeat overnight shifts on a more frequent basis. A decrease in available firefighters resulted in a firefighting function crisis due to burnout. Therefore, firefighters may have experienced higher levels of mental and emotional stress, which may have adversely impacted their well-being and quality of work [4].

However, very little attention has been paid to firefighters [1]. Many firefighters have been infected while on duty during the COVID-19 pandemic and may feel anxious or fearful of being infected. Hypochondriasis (illness anxiety disorder) is a state of excessive worry about serious diseases [5]. Based on the cognitive-behavioral model [6], an individual who fears being sick may seek reassurance. This reassurance-seeking behavior can reduce their anxiety, but repeated reassurance-seeking behavior can become preoccupied with the illness. This model was feasible among the general population [7], healthcare workers [8], and medical students [9] during the COVID-19 pandemic when we assessed their viral anxiety using the rating scale of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic-9 (SAVE-9) [10] or SAVE-6 [11]. Their repetitive reassurance-seeking behaviors, such as checking their physical symptoms or body temperatures, washing their hands, and searching for information on the internet paradoxically increases their viral anxiety and are preoccupied with the possibility of viral infection.

While working as a firefighter, they have the potential to witness people’s deaths. Firefighters can suffer depression, anxiety, worry [12], poor sleep quality [13], or post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms while working [14]. Especially during this pandemic, they would have witnessed the death of citizens, colleagues, or even family members [1]. The grief responses of firefighters are an issue that requires attention but has not yet been addressed in this pandemic. Healthcare workers reported that their grief response was higher [15] and associated with their mental health [16]. Like healthcare workers [17], firefighters were witnesses and victims. However, the emphasis was on the victim’s death rather than the firefighters who repeatedly suffered the death of others.

On the other hand, intolerance of uncertainty was considered an important psychological state [18], which can lead to heightened anxiety levels due to the inability to tolerate the aversive reactions that arise from not having sufficient, salient, or pertinent information. A firefighter must work in a risky environment, and he or she should keep an eye out to avoid infection at all times. We can posit that their intolerance of uncertainty can influence psychological distress. Among healthcare workers, intolerance of uncertainty was reported to be related to a high level of burnout [19,20] and adherence to physical distancing [21]. The influence of intolerance of uncertainty on firefighters’ viral anxiety needs to be explored.

In this study, we aimed to explore the feasibility of cognitive-behavioral model hypochondriasis regarding COVID-19 among firefighters. In addition, we examined whether their grief reaction from experiencing people’s death during this pandemic and their intolerance of uncertainty can be included in the model of COVID-related hypochondriasis. We hypothesized that 1) coronavirus reassurance-seeking behaviors of firefighters are positively correlated with a preoccupation with coronavirus, 2) viral anxiety of firefighters is positively linked to preoccupation with coronavirus, 3) pandemic grief reaction of firefighters is positively related to a preoccupation with coronavirus, 4) intolerance of uncertainty of firefighters is positively related to a preoccupation with coronavirus among cancer patients, and 5) intolerance of uncertainty at least partially mediates the relationship between pandemic grief reaction of firefighters on the cognitive-behavioral model of COVID-related hypochondriasis among firefighters.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

We conducted an anonymous online survey from October 27–28, 2022, among 317 firefighters affiliated with Gyeonggi-do, South Korea. The e-survey form, developed according to the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys guidelines [22], included questions on participants’ demographic variables such as sex, age, marital status, or year of employment. In addition, their type of work (emergency medical service, rescue activity, office work, or fire suppression) and shift working pattern (3-day or 21-day shift) were also collected. We asked participants about their experience of being quarantined due to infection with COVID-19, the experience of being infected with COVID-19, and receiving the COVID-19 vaccines. We collected 304 responses after excluding incomplete responses from the survey. Among 304 responses collected based on the Central Limit Theorem [23] (30 samples per cell of all 10 cells [sex×five age groups]), we performed subgroup analysis using 212 responses from participants who witnessed people’s death during the last two years. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center (2022-1293), and written informed consent for participation was waived.

Measures

Obsession with COVID-19 Scale

The Obsession with COVID-19 Scale (OCS) is a rating scale measuring an individual’s preoccupation with coronavirus [24]. It consists of four items rated on a 5-point Likert scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (nearly every day over the last two weeks). A higher level of total score reflects a greater level of preoccupation with the coronavirus. In this study, we applied the Korean version of the OCS [25]. Cronbach’s α among this sample was 0.822.

Coronavirus Reassurance-Seeking Behaviors Scale

The Coronavirus Reassurance-Seeking Behaviors Scale (CRBS) is a rating scale measuring an individual’s coronavirus-related reassurance-seeking behavior [26]. It consists of five items that can be rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0: not at all to 4: nearly every day). A higher level total score reflects a higher level of reassurance-seeking tendency. In this study, we applied the Korean version of the scale [27]. Cronbach’s α in this sample was 0.910.

Fear of COVID-19 Scale

The Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) is a self-report questionnaire to measure viral anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic [28]. There are seven items that can be rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher level indicates a higher level of viral anxiety. We applied the Korean version of FCV-19S [29] in this study, and Cronbach’s α among this sample was 0.896.

Pandemic Grief Scale

The Pandemic Grief Scale (PGS) is a rating scale measuring an individual’s dysfunctional grief associated with a COVID-19 death [30]. It consists of five items rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). A higher level of total score reflects a higher level of dysfunctional grief. The PGS scale was also developed to assess healthcare workers’ grief reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, we applied the Korean version of PGS validated among healthcare workers [31] after changing the terms “patient” into “people.” Cronbach’s α among this sample was 0.851.

Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12

The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12 (IUS-12) is a self-reporting scale for assessing one’s tolerance for uncertainty[32]. The questionnaire has 12 items that can be rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1: not at all characteristics of me to 5: completely characteristic of me). Higher total scores indicate a greater intolerance for uncertainty. We applied the Korean version of the IUS-12 in this study [33] Cronbach’s α in this sample was 0.910.

Statistical analysis

Demographic characteristics and rating scale scores are summarized as a mean and standard deviation. We defined the significance level of the analyses as two-tailed with a 0.05 level of significance. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between age and rating scale scores. A linear regression analysis was conducted using enter methods to investigate variables that predict preoccupation with coronavirus. Using mediation analysis, we examined the feasibility of a cognitive-behavioral model of hypochondriasis related to COVID among firefighters. After that, to examine whether pandemic grief or intolerance of uncertainty may mediate the influence of reassurance-seeking behavior or viral anxiety on the preoccupation with coronavirus, the bootstrap method was implemented with 2,000 resamples. The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS version 21.0, AMOS version 27 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and JASP 0.16.4 (JASP team, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

RESULTS

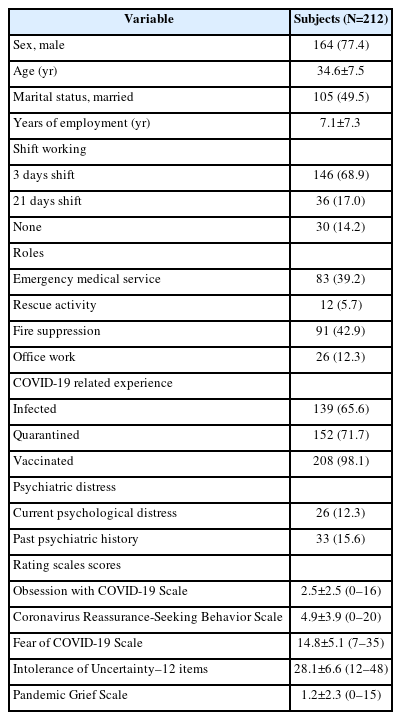

A total of 212 firefighters who witnessed people’s death during the last two years were collected. Their mean age was 34.6± 7.5 years, and their mean years of employment was 7.1±7.3 years. Among them, 164 (77.4%) were male, 105 (49.5%) were married, and 182 (85.9%) were shift workers (3 days shift or 21 days shift) (Table 1). They play a role in fire suppression (n=91, 42.9%), emergency medical service (n=83, 39.2%), office work (n=26, 12.3%), and rescue activity (n=12, 5.7%).

Female firefighters (n=48) showed more higher level in FCV-19S (t(210)=2.940, p=0.004), OCS (t(210)=3.897, p<0.001), CRBS (t(210)=2.360, p=0.019), and IUS-12 (t(210)=2.679, p=0.008) than male firefighters (n=164). However, there was no significant difference in the PGS score among female and male firefighters. Among shift working types and marital status, there was no significant difference in symptoms rating scales score. Among firefighters’ roles, the PGS, OCS, and CRBS scores were significantly higher among those in rescue activity than those in office work or fire suppression. However, the FCV-19S and IUS-12 scores were not significantly different based on their roles.

Their OCS score was significantly correlated with CRBS (r=0.74, p<0.001), FCV-19S (r=0.63, p<0.001), PGS (r=0.65, p<0.001), and IUS-12 scores (r=0.50, p<0.001) (Table 2). The CRBS was significantly correlated with FCV-19S (r=0.53, p<0.001), PGS (r=0.50, p<0.001), and IUS-12 (r=0.38, p<0.001). The FCV-19S was significantly correlated with PGS (r=0.53, p<0.001) and IUS-12 (r=0.47, p<0.001). The PGS was significantly correlated with IUS-12 (r=0.47, p<0.001).

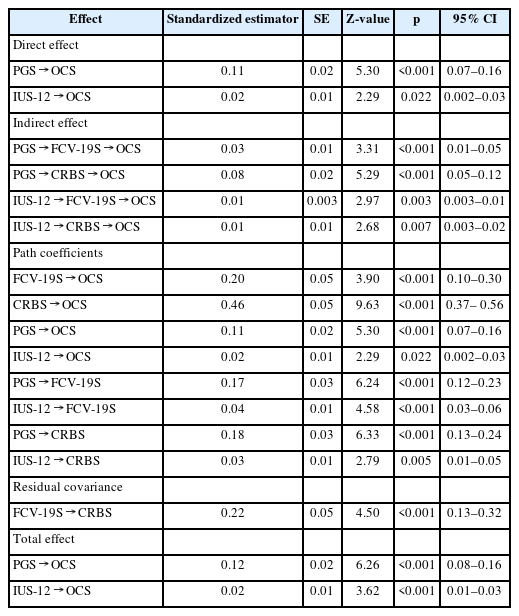

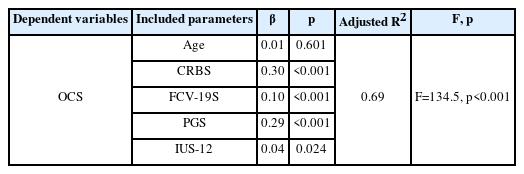

Linear regression analysis with enter methods was done to explore expecting variables for the preoccupation with coronavirus. It revealed that the CRBS (β=0.30, p<0.001), FCV-19S (β=0.10, p<0.001), PGS (β=0.29, p<0.001), and IUS-12 (β=0.04, p=0.024) (F=134.5, p<0.001) expected the OCS (Table 3).

Linear regression analysis to explore variables which expect preoccupation with coronavirus among firefighters who witnessed death (N=212)

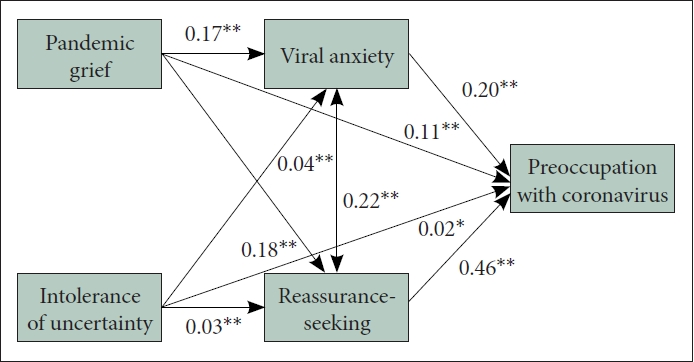

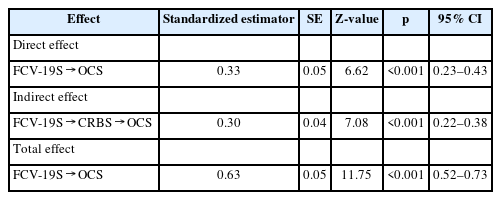

In the mediation model, we observed the COVID-related cognitive-behavioral model of hypochondriasis was feasible among firefighters who witnessed people’s death (Table 4). Pandemic grief reaction and intolerance of uncertainty directly influenced preoccupation with coronavirus (Table 5 and Figure 1). In addition, viral anxiety and coronavirus reassurance-seeking behavior mediated the influence of pandemic grief reaction and intolerance of uncertainty on the preoccupation with coronavirus.

The feasibility of the COVID-related cognitive-behavioral model of hypochondriasis among firefighters who witnessed people’s death (N=212)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we observed that the cognitive-behavioral model of COVID-related hypochondriasis is feasible among firefighters. Pandemic grief of firefighters who witnessed people’s death, and their intolerance of uncertainty directly influenced their preoccupation with the coronavirus. In mediation analysis, firefighters’ viral anxiety and coronavirus reassurance-seeking behavior mediated the influence of pandemic grief reaction or intolerance of uncertainty on the preoccupation with coronavirus.

This study observed that the PGS score was not significantly different between male and female firefighters, despite the significant difference in the FCV-19S, OCS, CRBS, and IUS-12 scores. We can speculate that grief responses to this pandemic can appear regardless of sex, even though the normative data of the PGS is not still available. Based on their roles, firefighters in the rescue activity had significantly higher levels of pandemic grief response, preoccupation with the virus, and coronavirus-related reassurance-seeking behavior than those in office work or fire suppression. In this pandemic, firefighters in the rescue activity had a role in transferring the infected people to the medical center, which might influence these results.

In the linear regression model, preoccupation with COVID-19 was expected by all rating scales, such as the CRBS, FCV-19S, IUS-12, and PGS. According to the cognitive-behavioral model, hypochondriasis is characterized by repetitive reassurance-seeking behavior that aggravates anxiety and increases preoccupation with exposure [6]. In the mediation model, we observed that the vicious cycle of COVID-related hypochondriasis is feasible among firefighters who witnessed people’s death during this pandemic. We can easily understand, using this model, how firefighters behave during the COVID-19 pandemic. They may seek repetitive reassurance (checking their physical symptoms or body temperature, washing hands, or searching the information) due to their high anxiety levels in response to the virus while in their role. Continuing reassurance-seeking behaviors can paradoxically lead to increased viral anxiety, resulting in preoccupation with the virus. They must stay with the infected person in the ambulance for an extended period while searching for a medical center that could provide medical care for the infected individual. If they are infected, they should be excluded from their roles while they are quarantined. As a result, their colleagues worked more due to their absence. We can speculate that it is the main reason for their pattern of hypochondriacal response in this pandemic. We also observed a similar pattern among healthcare workers [8]. Healthcare workers would prepare the infectivity while caring for infected patients, and their absence may influence their colleagues’ work-related stress [10]. They should regularly check their physical symptoms or body temperature and wash their hands. This pattern made them adhere to the physical distancing policy more [21].

This study also observed that firefighters’ pandemic grief response and intolerance of uncertainty could distribute COVID-related hypochondriacal responses. Pandemic grief response influenced their viral anxiety, reassurance-seeking behavior, and preoccupation with the virus. It is important to note that not all the deaths witnessed were caused by the virus. We could not collect the cause of death since it might not be easy for firefighters to know the exact reasons. However, we can observe that the grief response they experienced during this pandemic led to viral anxiety. We also observed similar results among healthcare workers who witnessed the death of the patients they cared for (unpublished, An, 2022). Among 267 healthcare workers who witnessed patients’ death, 61.4% reported that their experienced deaths were not related to COVID-19, but their grief rumination contributed to the hypochondriacal responses. Regardless of the cause of death of the individual, grief responses following their death in this pandemic may result in hypochondriacal responses to COVID-19.

Intolerance of uncertainty also contributes to the hypochondriacal response of firefighters, as a cognitive predisposition described as fear of the unknown, intolerance of uncertainty firefighters have might influence their viral anxiety, reassurance-seeking behavior, and preoccupation with the virus. During the COVID-19 pandemic, intolerance of uncertainty was reported to be a predictor for depression and anxiety among the general population[18]. It moderated the relationship between COVID-19 threat estimation and COVID-fear and safety behavior [34]. Phobia of social closeness among the general population was also reported to be related to intolerance of uncertainty [35]. Among healthcare workers, it was reported that intolerance of uncertainty was one of the factors for psychological stress, contributing to adherence to the physical distancing policy [21]. Firefighters’ intolerance of uncertainty influences their hypochondriacal responses to coronavirus, and resultantly it may act as a double-edged sword. Preoccupation with coronavirus makes them adhere to physical distancing and is a preventive measure for their health status and those they care for. However, their job roles during the pandemic stressed them. It is necessary to conduct further research to better understand how to manage their hypochondriacal responses to reduce their work-related stress and enhance the preventive component.

The study has some limitations. First, this survey was conducted among 212 firefighters affiliated with Gyeonggi-do, South Korea. In 2021, 1,227 of 64,768 all firefighters in South Korea were affiliated with Gyeonggi-do [36]. Participants in this study were 17.3% of them in Gyeonggi-do and 0.3% of them in South Korea. The interpretation of these results needs to be done with caution. Second, this survey was conducted anonymously online, and the responses from the participants can be biased due to misunderstanding. Third, the study was conducted October 27–28, 2022, approximately three years after the pandemic’s start. It is possible that participants have already adjusted to this pandemic, and the results might have been affected. However, during this period in South Korea, the third peak of the infection rate began to emerge [37], and participants were not free from infection risks. Finally, about 77.4% of the participants were male. We have reported that female participants had a high level of viral anxiety [38], and the predominance of male participants might influence the results.

In conclusion, the cognitive-behavioral model of COVID-related hypochondriasis is feasible among firefighters who witnessed people’s death during this pandemic. In addition, their pandemic grief response and intolerance of uncertainty contributed to the model. The study suggests that firefighters may require targeted interventions and support to manage their psychological distress, particularly female firefighters and firefighters engaged in rescue activity. Moreover, the study’s results demonstrate the importance of addressing pandemic grief reactions and intolerance of uncertainty, which could drive firefighter stress and anxiety related to COVID-19.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Seockhoon Chung, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: all authors. Data curation: Seockhoon Chung, Han-Sung Lee, Soomin Jang, Jeong-Hyun Kim. Formal analysis: Seockhoon Chung, Han-Sung Lee, Soomin Jang, Yong-Wook Shin, Jeong-Hyun Kim. Funding acquisition: Seockhoon Chung. Investigation: Seockhoon Chung. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: Seockhoon Chung. Visualization: Seockhoon Chung. Writing—original draft: Seockhoon Chung, Han-Sung Lee, Jin Yong Jun. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

None

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the firefighters in Gyeonggi-do who volunteered to participate in the survey and all those who are fighting against COVID-19 in Korea.