Agoraphobia and Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Levels between Tamoxifen and Goserelin versus Tamoxifen Alone in Premenopausal Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: A 12-Month Prospective Randomized Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Tamoxifen is an estrogen receptor antagonist used to prevent recurrence of breast cancer, which may provoke depression and anxiety and increase follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) to patients. We compared anxiety and depression symptoms and FSH levels who received conventional tamoxifen alone and combination treatment of goserelin, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue, with tamoxifen.

Methods

Sixty-four premenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive early-stage breast cancer were included and were assigned randomly to receive either tamoxifen and goserelin combination or tamoxifen alone for 12 months. The participants were evaluated blindly using the Hamilton Depression and Anxiety Rating Scale, the Beck Depression Rating Scale, and the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (APPQ). Blood FSH levels were assessed at baseline, 6 and 12 months.

Results

A significant time×group difference was detected in the agoraphobia trends subscale of the APPQ and in FSH levels. The combination group showed significantly less increases in agoraphobia subscale of APPQ and greater decreases in FSH level than those in the tamoxifen-alone group from baseline to 12 months of treatment. No significant differences for age, tumor grade, body mass index, or family history were found at baseline between the two groups.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the combination treatment of tamoxifen and goserelin resulted in less agoraphobia than tamoxifen alone in premenopausal women with breast cancer, which may associated with FSH suppression of goserelin.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a sex hormone-dependent disease. Approximately 60% of breast cancers in premenopausal women are hormone receptor positive (HR+). Adjuvant endocrine therapy reduces tumor recurrence and mortality in premenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive, progesterone receptor-positive, or both.1 Recently, diverse types of approach for endocrine therapy has developed and been tested under trials.

Tamoxifen is a selective modulator of estrogen and has been the standard care for premenopausal women with HR+ breast cancer for many ayears.234 The anti-cancer effect originates from binding estrogen receptors on tumors. This binding produces a nuclear complex that decreases DNA synthesis and inhibits the effects of estrogen. Tamoxifen increases plasma estradiol concentrations by interfering with the normal negative pituitary feedback mechanisms,56 and the resulting follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) rise drives ovarian steroidogenesis and increased incidence of ovarian cysts.7

Goserelin is a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue acts on the pituitary gland in the brain.8 Administration of goserelin with chemotherapy appeared to protect against ovarian failure, reducing the risk of early menopause and improving prospects for fertility.9 Initially, goserelin causes an increase in the amount of FSH and LH released from the pituitary gland, but chronic administration act by downregulating pituitary GnRH receptors, thereby suppressing the release of luteinising hormone (LH) and FSH.10 Goserelin reduces plasma/serum FSH and circulating sex hormone levels in premenopausal women to postmenopausal levels.1112

The treatment effect of tamoxifen plus goserelin for breast cancer has been controversial. However, the recent study results of the Suppression of Ovarian Function Trial (SOFT) and the Tamoxifen and Exemestane Trial (TEXT) showed that ovarian function suppression with goserelin improved the survivals in premenopausal breast cancer patients after adjuvant chemotherapy.1314

One of the major side effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in young patients with breast cancer is treatment-associated premature menopause.15 Many previous studies have reported that changes of hormone levels are closely related to depression and anxiety disorders.161718 Compared to normal menopause, treatment-associated menopause is more abrupt in onset and more persistent. Treatment-associated menopause has been linked to poor health perception, leading to increased emotional stress and anxiety, particularly in young patients with breast cancer.19 Even in a general population of women without lifetime history of psychiatric diseases, women who enter the menopausal transition earlier have a significant risk for first onset of depression.20 However the adverse effects of goserelin have not been studied well in young patients with breast cancer.

The aim of this study was to compare anxiety and depression symptoms of premenopausal women with HR+ early-stage breast cancer who received either a combination of tamoxifen plus goserelin or tamoxifen therapy alone, using psychological measures, and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels, in a 12-month prospective randomized trial.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 64 patients with breast cancer were recruited from the outpatient clinic of the Breast and Endocrine Surgery Center of Samsung Medical Center between January 2011 and December 2014. Patients were eligible to participate in the study after meeting the following inclusion criteria: age <50 years and premenopausal women with histologically-proven, HR+ (defined as ER ≥10% and/or PgR ≥10%) early invasive breast cancer.

The patient exclusion criteria were: age >50 years, natural menopause, GnRH level ≥40 pg/mL, pregnancy or lactation, and uncontrolled heart failure or coronary heart disease in the previous 6 months. Those with a psychotic disorder (e.g., schizophrenia or delusional disorder), bipolar affective disorder, or neurological illness, including significant cognitive impairment or Parkinson's disease, mental retardation, a significant medical condition, epilepsy, history of alcohol or drug dependence, personality disorder, or brain damage were excluded.

Study procedures

Eligible patients were randomized using a 1:1 allocation to one of the two treatment groups from the date of randomization. One group of patients received a combined treatment of tamoxifen and goserelin (n=32), and the second group received tamoxifen alone (n=32) for 12 months. All patients attended three visits at baseline and at 6 and 12 months after treatment was initiated. Patients who were unable to tolerate the study medications per protocol were withdrawn from the study. This study protocol was approved by the ethics review board of Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. Signed informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Baseline psychological evaluation

Psychiatrists with more than 3 years of clinical experience evaluated the participants' psychiatric and medical histories and confirmed their eligibility. A trained psychologists blinded to the psychiatrists' assessment evaluated the participants' psychiatric diagnoses and current mood states using the Korean version of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).21 The psychiatric evaluations were administered by a single trained rater at baseline and at 6 and 12 months.

Psychological measurements

The primary outcome measures were the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D)22 and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A)23 scores of the participants. The secondary outcome measures were changes in the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score.24 The Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire (APPQ),25 and the Anxiety Sensitivity Index-Revised (ASI-R)26 scores were obtained and FSH levels were measured at each visit. In addition, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ)27 and the Hypomania Checklist (HCL-32) were employed to measure the severity of previous hypomanic episodes.28

The current anxiety sensitivity level of the participants was assessed using the ASI-R. The Korean version of the ASI-R has demonstrated a high internal consistency coefficient (α=0.92) and a good test-retest reliability (r=0.82).29 The APPQ is a 27-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure fear of agoraphobic situations (Agoraphobia, 9 items), fear of social situations (Social phobia, 10 items), and fear of activities that produce somatic sensations (interoceptive fear, 8 items). The Korean version of the APPQ has excellent psychometric properties, which are similar to the original APPQ.30 The BDI is a well-performing, 21-item, self-report questionnaire designed to assess and evaluate the frequency of depressive symptoms over a 1-week period. We administered the Korean version of the BDI,31 which has demonstrated good psychometric properties.

FSH levels

Blood (10 mL) was taken from the cubital vein of each participant into 1) heparinized vacuum containers (plasma), 2) additive-free vacuum containers (serum), and 3) EDTA vacuum containers (for platelet count). FSH was measured using a chemiluminescence immunoassay and an ADVIA Centaur automated analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, New York, NY, USA). The assay detection limit was 0.3 IU/L.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square or Fisher's exact test were used to compare sociodemographic and clinical categorical data between the two groups, and the t-test was used for normally distributed continuous variables. The primary efficacy measures were changes in the HAM-D and HAM-A scores and from baseline to 12 months. The Linear Mixed Model was applied to repeated measurements (after natural log transformation due to non-normality in some cases). Blood FSH levels had skewed distributions and were transformed using the natural log. The Generalized Linear Mixed model was applied to repeated ordinal outcomes. Time, group and time×group were considered fixed effects and subject was considered a random effect.

We performed simple and multiple linear regression analysis for univariable analysis and multivariable analysis, respectively. Variables with a p-value of less than 0.2 in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable analysis.

Two-tailed p-values<0.05 were considered significant and were corrected using Bonferroni's method for multiple testing. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS ver. 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

The demographic and clinical profiles of the patients are shown in Table 1. No differences in the demographic or clinical variables were detected at baseline between the two treatment groups. The mean age of the combined treatment group was 44.75±3.26 years and that in the tamoxifen-alone group was 44.97±3.26 years.

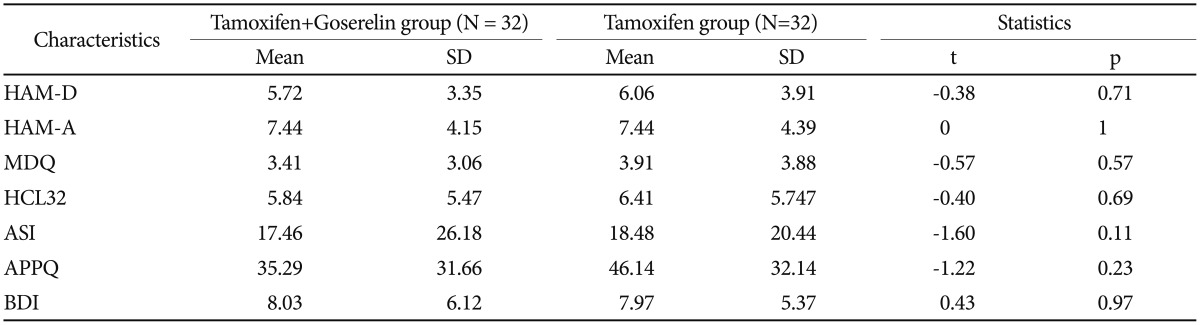

Table 2 presents the baseline psychological characteristics. Mean baseline HAM-D scores were 5.72±3.53 vs. 6.06±3.91 in the combined treatment and tamoxifen-alone groups, respectively. No differences were observed in HAM-D, HAM-A, MDQ, HCL-32, ASI and APPQ scores at baseline (Table 2). No differences in baseline FSH levels were detected between the treatment groups (Table 1 and 2).

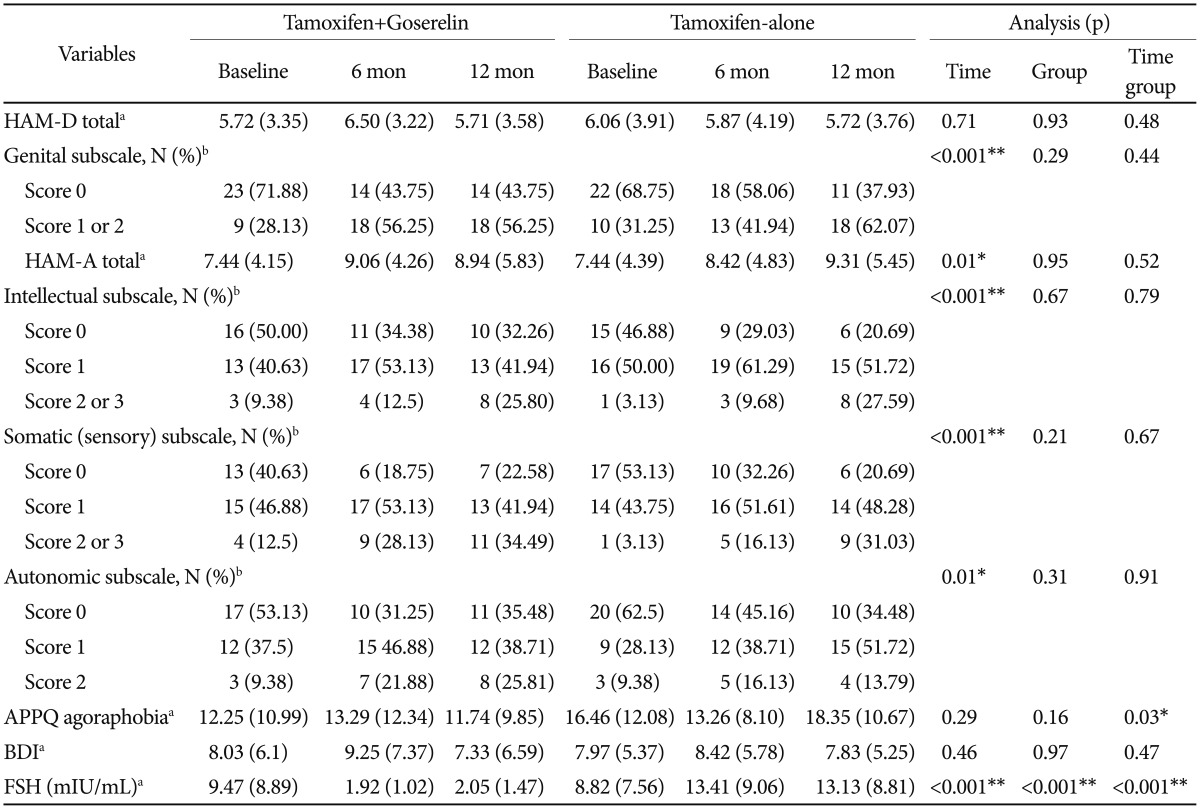

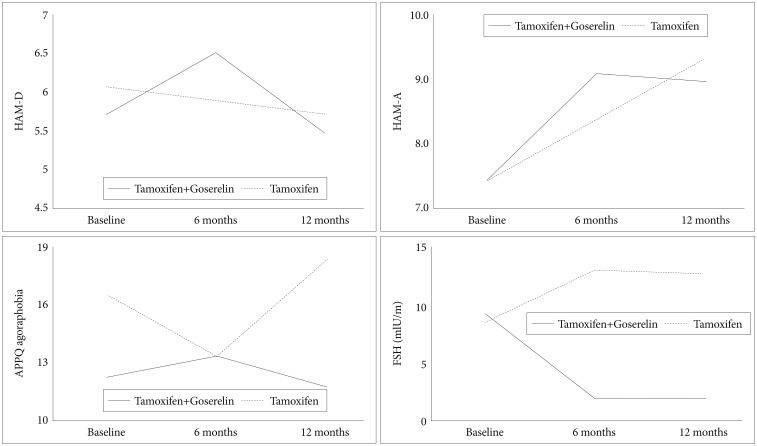

Table 3 shows the psychological characteristics of the patients in the two groups. A significant time×group difference was detected in the agoraphobia trends subscale of the APPQ and in FSH levels (Figure 1) between the two groups after 12 months of treatment. The tamoxifen and goserelin group showed significantly less of an increase in APPQ agoraphobia subscale score but a greater decrease in FSH level than those in the tamoxifen-alone group from baseline to 12 months of treatment. No significant time, group, or time×group differences were observed in the HAM-D and BDI score between the two groups (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Psychological characteristics of the patients with breast cancer assigned randomly to 12 months of treatment with tamoxifen and goserelin or tamoxifen alone

Linear Mixed Model Analysis and mean changes in the psychological scale scores between patients with breast cancer assigned randomly to the tamoxifen and goserelin or the tamoxifen-alone treatment. HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, HAM-A: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, ASI: Anxiety Sensitivity Index, APPQ: Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire, FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone.

A time-dependent ascending trend was detected in the total HAM-A score (β coefficient=1.90, p=0.01) (Table 3 and Figure 1), the HAM-D genital symptom subscale score (β coefficient=4.07, p<0.001), and the HAM-A intellectual (p<0.001), somatosensory (p<0.001), and autonomic symptom (p=0.01) subscales. The total HAM-D scores of all patients after 12 months of treatment were ≤7 points (no depression).32 A total of 41.9% of the combined treatment group and 44.8% of the tamoxifen-alone group showed moderate to severe anxiety.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to compare anxiety and depressive symptoms and FSH levels between premenopausal women with breast cancer who received either a combined tamoxifen and goserelin treatment or a tamoxifen-alone treatment. The tamoxifen and goserelin group showed significantly less of an increase in agoraphobia symptoms but a greater decrease in FSH level than those in the tamoxifen-alone group from baseline to 12 months of treatment, whereas no differences were observed in depressive symptoms between the groups.

It is a unique finding of this study that agoraphobia symptoms are found in premenopausal women with breast cancer during anti-cancer treatment with tamoxifen. Agoraphobia is a type of anxiety symptoms which characterized by anxiety in situations where the sufferer perceives the environment to be dangerous, uncomfortable, or unsafe, which can include wide-open spaces, uncontrollable social situations, unfamiliar places, shopping malls, airports, and bridges. Although agoraphobia became independent of panic disorder in the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5), agoraphobia commonly occurs in patients with panic disorder.33 Although previous preclinical studies revealed that tamoxifen treatment may provoke anxiety symptoms due to antagonize the effects of ovarian hormones in preclinical studies,3435 human studies showed that changes in anxiety, mood, and sexual functioning were not significantly associated with treatment of tamoxifen in placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized, controlled trials that investigated the efficacy of tamoxifen in the prevention of breast cancer in women who are at high familial risk.36

This study showed that tamoxifen and goserelin group showed significantly less of an increase in agoraphobia symptoms than tamoxifen-alone group. Goserelin is a GnRH analogue that increases FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) synthesis, leading to increase levels of circulating sex steroids.37 In this study, FSH levels were suppressed remarkably in the combined treatment group relative to those in the tamoxifen-alone group. Mean FSH level in the tamoxifen-alone group peaked within the first 6 months, and then tended to stabilize at a high level. In contrast, mean FSH level in the combined treatment group decreased and remained stable.

Previous studies have revealed that anxiety is commonly found in women in perimenopause,38 in those with premenstrual dysphoric disorder,39 and in the postpartum,40 indicating fluctuations in hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis activities that may result in anxiety symptoms. A previous study showed that perimenopausal fluctuation of FSH level may interact with the psychosocial environment of midlife stress to contribute to perimenopausal anxiety and depression risk through alterations in regulation of the HPA axis by γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).41 This suggests that suppress FSH fluctuation from combination treatment of goserelin and tamoxifen can reduce anxiety symptoms among breast cancer patients, because breast cancer patients experience high stress due to cancer diagnosis, regular checks for recurrence, and body changes from breast surgery.42

Another possible effects of a decrease in estrogen levels on the serotonin system4344 have been associated with psychiatric symptoms. Women with breast cancer are at higher risk for experiencing hot flushes, which are largely attributable to systemic cancer treatment and their effects on estrogen levels.45 Menopausal symptoms and complications, such as hot flushes, sweating, and heart palpitations, are related to anxiety in breast cancer survivors.46 Hot flush severity is also associated with higher FSH and lower estrogen levels, early menopause, beginning the late menopausal stage at a younger age, and greater anxiety.47

Our results should be considered in light of several limitations. Although the sample size was moderate, a larger sample size could offer more certain conclusions. We did not measure gonadal sex steroid hormone levels, such as estrogen and progesterone; thus, we could not evaluate the direct causal relationship between anxiety and these hormone levels. The relationship between hormonal changes and mood before and after adjuvant endocrine therapy is complex and appears to be influenced by study design and multiple psychiatric and environmental factors. A future study should have a longer treatment period with more frequent follow-up visits to accurately assess changes in hormone levels and mood symptoms. More accurate clinical assessments and use of validated measures would allow menopause-related somatic complaints and psychological symptoms to be distinguished at greater levels for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that the combined tamoxifen and goserelin treatment for premenopausal women with breast cancer resulted in less frequent agoraphobia symptoms than those observed with tamoxifen alone. Both treatment regimens increased somatic anxiety levels. Therefore, agoraphobia and anxiety symptoms should be carefully observed in patients treated for breast cancer with anti-estrogen therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Institute for Information & communications Technology Promotion (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIP) (No. B0132-15-1003, the development of skin adhesive patches for the monitoring and prediction of mental disorders) and the Samsung Medical Center Clinical Research Development Program (CRDP) Grant SMO1131461 and Samsung Medical Center Grant (SMO1161491). This research was also supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI14C3418). The authors declare no potential competing interests with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.