A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Nonpharmacological Interventions for Moderate to Severe Dementia

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Due to limited efficacy of medications, non-pharmacological interventions (NPI) are frequently co-administered to people with moderate to severe dementia (PWMSD). This systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the effects of NPI on activities of daily living (ADL), behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), and cognition and quality of life (QoL) of PWMSD.

Methods

A literature search was conducted in the following databases: Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE, Medline, CIHNAL, PsycINFO, KoreaMED, KMbase, and KISS. We conducted a meta-analysis on randomized controlled trials and used the generic inverse variance method with a fixed-effects model to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD). The protocol had been registered (CRD42017058020).

Results

Ten randomized controlled trials met the inclusion criteria of the current meta-analysis. NPI were effective in improving ADL [SMD=0.28, 95% confidence interval (CI)=0.11–0.45] and reducing depression (SMD=-0.44, 95% CI=-0.70– -0.19). However, NPI were not effective in reducing agitation, anxiety, or overall, or improving cognitive function. In a subgroup analysis, music therapy was effective in reducing overall BPSD (SMD=-0.52, 95% CI=-0.90– -0.13).

Conclusion

Albeit the number of studies was limited, NPI improved ADL and depression in PWMSD.

INTRODUCTION

People with dementia (PWD) experience gradual but progressive loss of cognition, and more than half of them suffer from behavioral and psychological symptoms [1]. However, the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists is limited, particularly in cases of moderate to severe dementia [2-5]. As such, new anti-dementia drugs in clinical trials are targeting prodromal or early-stage dementia [6]. Antipsychotics, which are commonly prescribed for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), are associated with serious adverse effects, including pneumonia, cardiovascular events, stroke, fractures, and kidney failure [7,8]. Above all, pharmacological interventions cannot fulfill the needs of PWD and their caregivers, including relief of pain and discomfort, the need for social contact, and alleviation of boredom [9]. For these reasons, a combination of pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions (NPI) is strongly recommended for PWD [10-13].

Recent systematic reviews have identified the effects of various NPI on cognitive decline [14-16], BPSD [12-17], activities of daily living (ADL) [14,16,18] and quality of life (QoL) [14] of PWD. However, most analyses in previous systematic reviews did not take into account the severity of dementia [17,19-23]. Although there have been several systematic reviews focused on the effects of NPI in people with moderate to severe dementia (PWMSD), they did not conduct meta-analyses [24,25] or conducted a meta-analysis on the effects of NPI in PWMSD as a subgroup analysis only [15,26,27]. In this study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of NPI on the cognitive function, BPSD, and ADL of PWMSD.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement [28] and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [29]. The study protocol was previously published [30], and it is registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, CRD42017058020).

Search strategy

We identified the studies that investigated the efficacy of NPI in PWMSD through bibliographic databases such as the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EBSCO-EMBASE, Proquest-Medline, ProQuest-PsycINFO, EBSCO-CINAHL, KoreaMED, KMbase, and Koreanstudies Information Service System. We also searched the reference lists of previous systematic reviews on the efficacy of NPI in PWD to extract relevant papers.

The search strategy combined several Medical Subject Headings or Emtree terms of population and intervention to identify relevant studies. The search terms were adapted using truncation or Boolean operators with database-specific terms. The population included PWMSD who were identified using the following search terms: [Dementia; Alzheimer Disease; Dementia, Vascular; Lewy Body Disease; Frontotemporal Dementia; Hydrocephalus, Normal Pressure; Huntington Disease; Neurodegenerative Disease; alcohol related dementia; mental disorder*; Parkinson’s disease dementia; moderate; severe; moderate to severe; advanced; profound]. Interventions included any NPI identified using the following search terms: [Psychotherapy; Cognitive Therapy; Behavior Therapy; Aromatherapy; Massage; Music Therapy; Animal Assisted Therapy; Exercise; Art Therapy; Horticultural Therapy; Occupational Therapy; Telerehabilitation; Therapy, Computer-Assisted; Dance Therapy; Play Therapy; Reality Therapy; Recreation Therapy; non pharmacological; non drug; light therap*; snoezelen; multimodality therap*; multisensory; doll therapy; robot therapy; cognitive training]. The literature searches were conducted April 18, 2017.

Study selection and inclusion criteria

We exported the search results to EndNoteTM X8 (Clarivate Analytics, USA), and three reviewers (RN, JY, and YY) independently assessed the results for inclusion by title, abstract and full text. Other reviewers (YJK, SB, KWK, and KK) resolved any discrepancies among the initial three reviewers regarding the selection of studies.

The systematic review included studies involving people with any type of dementia according to the standardized diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [31-33]; the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision [34]; the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association [35,36]; or other recommended diagnostic criteria. To be considered moderate to severe, dementia had to meet one of the following criteria: a Clinical Dementia Rating score [37] of 2 or more, a Global Deterioration Scale [38] score of 5 or more, a Functional Assessment Staging [39] score of 5 or more, or a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE40) score of 20 or less. If the range of severity score was not reported, the determination of severity was based on the mean and standard deviations score of the MMSE. The intervention criteria had no restrictions regarding category of NPI of practice guidelines [41].

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-RCTs, non-RCTs, cross-sectional studies, interrupted time series, and before-after studies that used the Study Design Algorithm for Medical Literature on Intervention [42]. We limited the publication languages to English and Korean, but did not limit the geography, time of the study, or publication year.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes included ADL and BPSD; secondary outcomes included cognitive function and QoL. These outcomes were evaluated using standardized scales for validity.

Data extraction

Three reviewers (RN, JY, and YY) independently extracted relevant data from articles using a standardized form. The form included details of the participants (e.g., number of patients, characteristics, demographics, and dementia severity), interventions (e.g., type, provider, period of intervention, and setting), and results (e.g., outcome, measurement scales, and result data). Other reviewers (YJK, SB, KWK, and KK) resolved any disagreements among the initial reviewers.

Assessment of methodological quality

Three reviewers (RN, JY, and YY) independently assessed the studies’ methodological quality and risk of bias (RoB) according to standardized tools and criteria. All reviewers discussed the quality of each study if the initial reviewers disagreed. We evaluated the RoB of RCTs using the RoB scale [43], and the quality of evidence for outcomes using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE44). All reviewers conferred regarding the quality of the evidence according to the GRADE guidelines [44].

Data analysis

We conducted meta-analyses on RCTs that reported the efficacy of NPI using valid scales, and attempted to contact the authors of studies with missing data to obtain the relevant information. We synthesized the published data and the data obtained from the authors. We used the generic inverse variance method with a fixed-effects model to calculate the standardized mean difference (SMD), as the included studies assessed the same outcomes but measured them using a variety of scales [29]. We performed subgroup analysis to assess whether differences in treatment affected outcomes. We utilized the fixed-effects model for the following reasons: 1) the population groups of included studies were similar, and 2) there was a limited number of studies to synthesize. The meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager, version 5.3 (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration). We assessed heterogeneity using chi-squared and I-squared tests. We did not evaluate publication biases due to an insufficient number of studies [29].

RESULTS

Study identification and selection

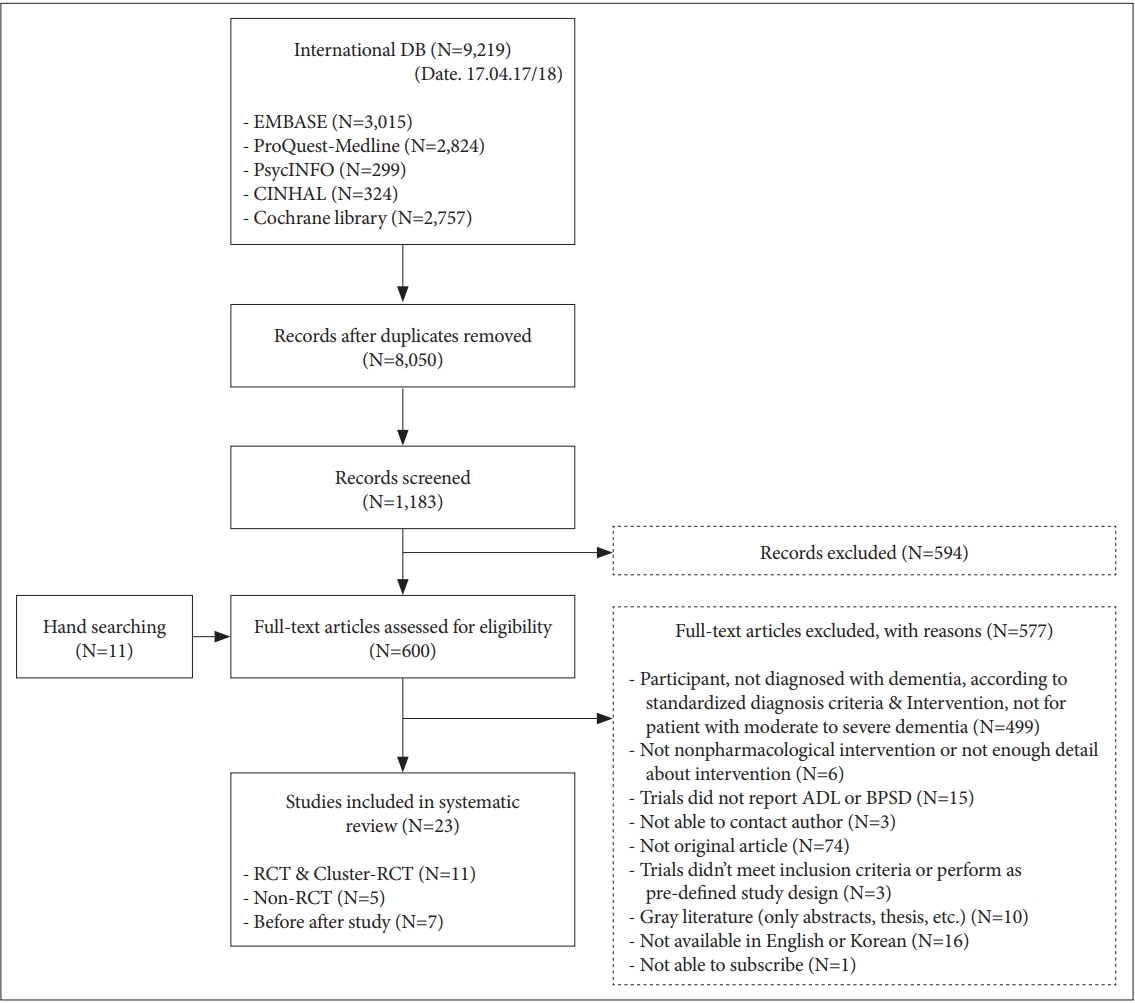

We identified 9,219 references in the selected databases. After removing the duplicates and clearly irrelevant articles, we retrieved 1,183 full-text records. Of these, we excluded another irrelevant 594 references and added 11 additional references identified by the authors, leaving 600 full-text references to be assessed for eligibility. Of these, we excluded 577 studies, as they did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Finally, there were 23 studies eligible for inclusion. Among them, only 10 RCTs [45-54] and one Cluster-RCT [55] met the criteria for meta-analysis (Figure 1).

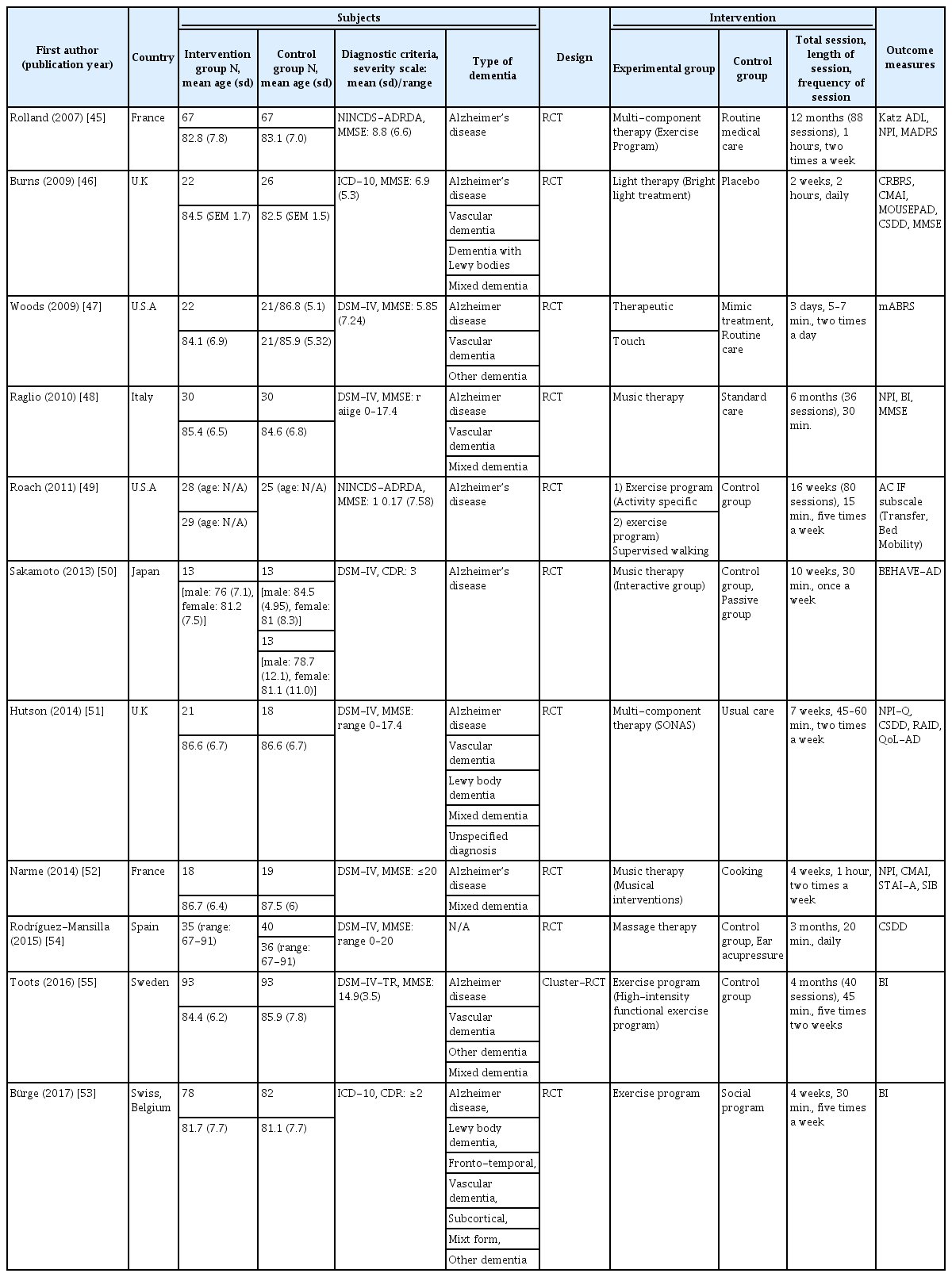

Characteristics of included studies

Characteristics of the ten RCTs [45-54] and one Cluster-RCT [55] are summarized in Table 1. These eleven studies included 960 PWMSD (intervention group: 456; control group: 504). Ten studies included patients with Alzheimer’s disease; six studies included patients with vascular dementia or other types of dementia such as Lewy body dementia or frontal dementia. All interventions provided to PWMSD in these studies utilized stimulation-oriented approaches [41]. Three interventions used music and exercise therapies, two used multi-component therapies, two used massage (including therapeutic touch) therapies, and one used light therapy.

The validity of the instruments employed in the studies to evaluate primary and secondary outcomes depended on the study references: Katz ADL [56], Barthel Index [57,58], and Crichton-Royal Behavioural Rating Scale [59] for ADL; Neuropsychiatric Inventory [60,61], Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire [62], Behavior Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale [63], and Manchester and Oxford Universities Scale for the Psychopathological Assessment of Dementia [64] for overall BPSD; Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia [65], and Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [66,67] for depression; Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory [68], and modified Agitated Behavior Rating Scale [69] for agitation; Rating Anxiety in Dementia [70] and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults [71] for anxiety; and MMSE and Severe Impairment Battery [72] for global cognitive function.

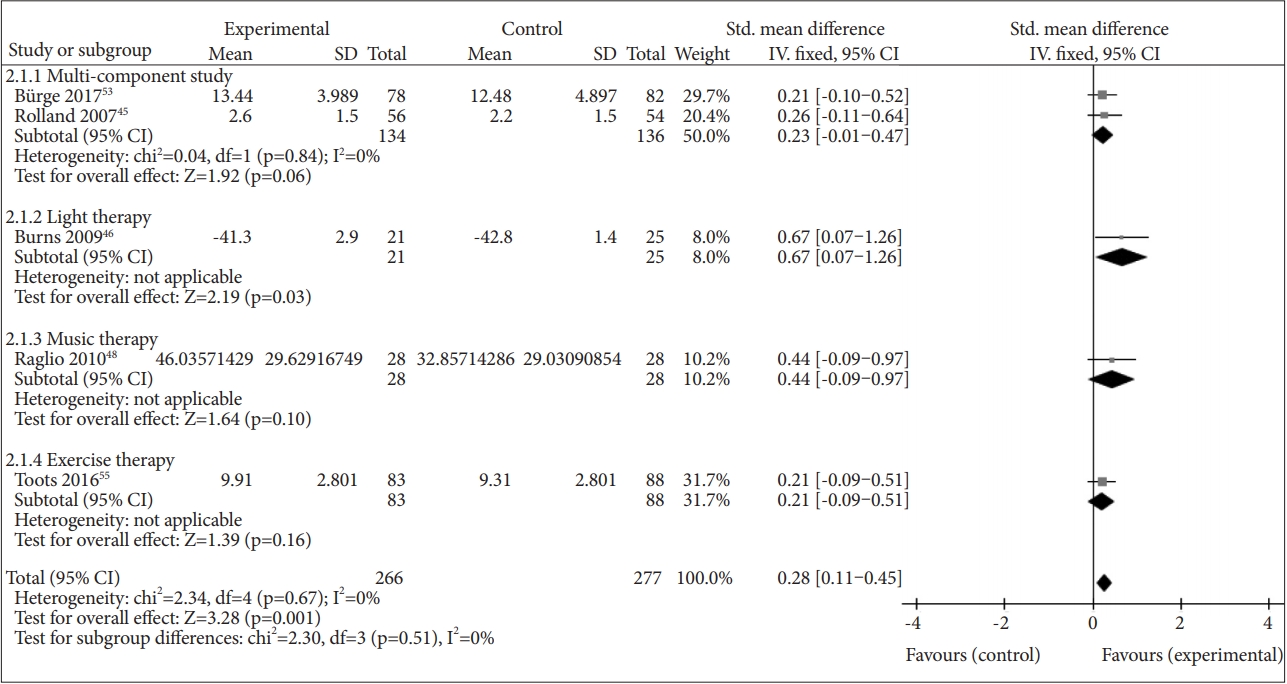

Effects of NPI on ADL

Six studies reported the effect of NPI on ADL: multi-component therapies in two studies [45,53], exercise therapies in two studies [49,55], light therapy in one study [46], and music therapy in one study [48]. We excluded one study [49] from the meta-analysis because it reported only subscale results. NPI had a beneficial effect on ADL when compared to the control [SMD=0.28, 95% confidence interval (CI)=0.11–0.45, p=0.001]. There was no heterogeneity across the trials (I2=0%) (Figure 2).

Effects of NPI on BPSD

Six studies reported the effect of NPI on the overall BPSD: multi-component therapies in two studies [45,51], music therapies in three studies [48,50,52], and light therapy in one study [46]. NPI did not show a beneficial effect on the overall BPSD when compared to the control (SMD=-0.16, 95% CI=-0.39–0.06, p=0.16). The heterogeneity between studies was considerable (I2=81%) [29]. In the subgroup analysis, music therapy showed a beneficial effect on the overall BPSD compared to the control (SMD=-0.52, 95% CI=-0.90– -0.13, p=0.008), but there was high heterogeneity between studies (I2=90%) [29] (Figure 3).

There were four studies that reported the effect of NPI on depression separately: multi-component therapies in two studies [45,51], light therapy in one study [46], and massage therapy in one study [54]. Compared to the control, NPI had a positive effect on depression (SMD=-0.44, 95% CI=-0.70– -0.19, p=0.0007), but the heterogeneity between studies was substantial (I2=93%) (Figure 4).

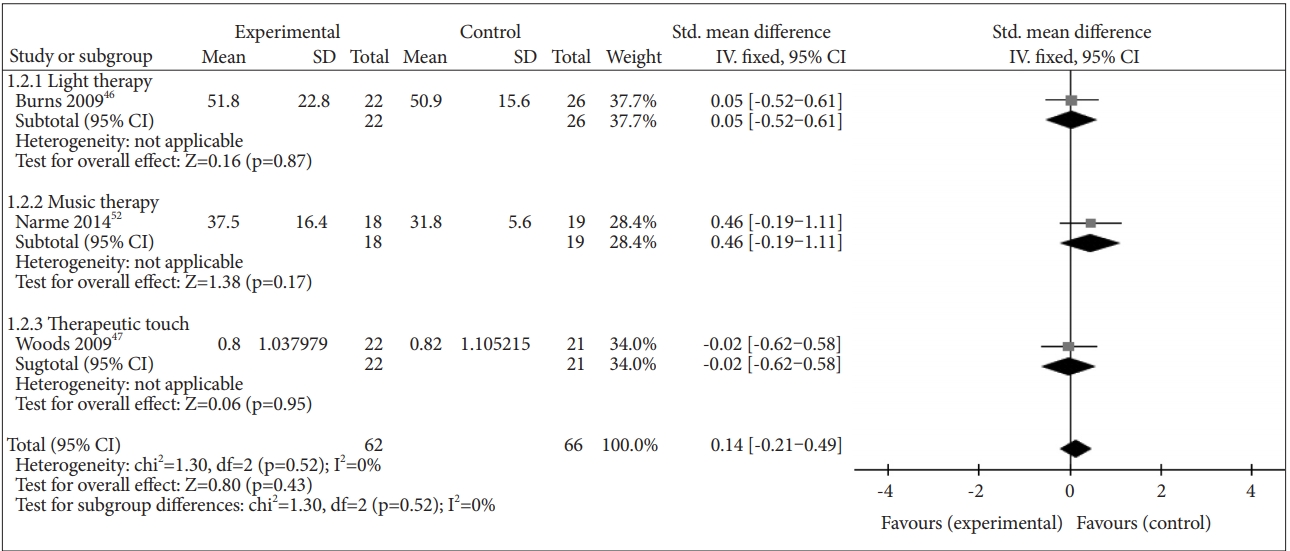

Three studies reported the effect of NPI on agitation separately: [46,47,52] light therapy in one study [46], music therapy in one study [52], and massage therapy in one study [47]. NPI did not have a beneficial effect on agitation (SMD=0.14, 95% CI=-0.21–0.49, p=0.43), and there was no heterogeneity between studies (I2=0%) (Figure 5).

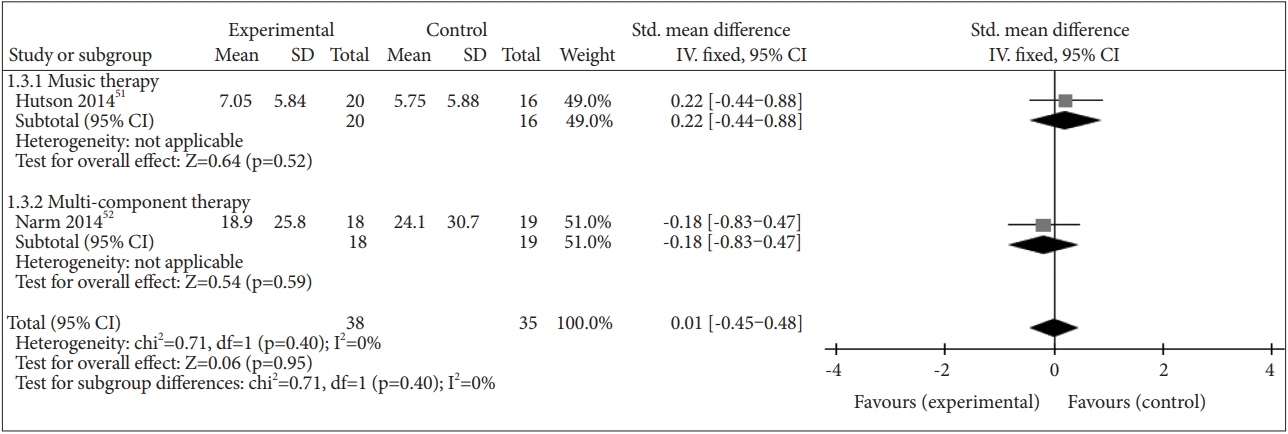

We identified two studies that reported the effect of NPI on anxiety separately: [51,52] multi-component therapy in one study [51] and music therapy in one study [52]. NPI did not have a beneficial effect on anxiety (SMD=0.01, 95% CI=-0.45–0.48, p=0.95), and there was no heterogeneity between studies (I2=0%) (Figure 6).

Effects of NPI on cognitive function

Three studies evaluated the effect of NPI on cognitive function: music therapy in two studies [48,52] and light therapy in one study [46]. NPI did not have a beneficial effect on cognitive function (SMD=0.30, 95% CI=-0.04–0.64, p=0.08), and there was no heterogeneity between studies (Figure 7).

Effects of NPI on QoL

Since there was only one study that reported the effect of multi-component study on QoL, we did not conduct a meta-analysis on the effect of NPI on QoL [51]. In that study, NPI were not beneficial to QoL when compared to the control (SMD=-0.65, 95% CI=-4.79–3.49, p=0.76).

DISCUSSION

Results of the current study are summarized in Table 2. NPI were shown to improve ADL of PWMSD. Although the current meta-analysis encompassed a wide range of NPI such as exercise therapy, light therapy, music therapy, and multi-component therapy, there was no heterogeneity between studies and subgroups. Light therapy had a strong beneficial effect on ADL when compared to the control. Although the efficacies were not statistically significant, other therapies also improved ADL. In previous systematic reviews on the effect of NPI on ADL of people with dementia of any severity, exercise therapy and light therapy were beneficial in improving ADL [14,23]. Since the study on light therapy was weighted as low as 8% in the meta-analysis, we cannot conclude the differential efficacy of NPI on ADL by intervention type (Table 2).

In the current study, NPI were not effective in reducing the overall BPSD, agitation, or anxiety. However, in the subgroup analyses, music therapy was effective in reducing the overall BPSD with a medium effect size. Two previous meta-analyses reported small to moderate effects of music therapy on BPSD in people with dementia of any severity [17,22], while one meta-analysis by Chang et al. [26] reported no benefits of music therapy on BPSD in PWMSD [26]. However, 4 out of 6 studies included in their meta-analysis did not meet the inclusion criteria for the current meta-analysis; one was not a RCT [73], one did not use formal criteria to diagnose dementia [74,75], and the other included mild dementia in the analysis [76].

Although NPI had a medium-size effect on depression in PWMSD, this result should be interpreted with caution due to high heterogeneity and low certainty of the evidence. The subgroup analyses showed that massage therapy, though weighted only 18.1%, was effective in reducing depression in PWMSD. Previous systematic reviews on the effects of NPI on depression in people with dementia of any severity [15,16,77-80] also showed that massage therapy was effective in reducing depression.

NPI were not shown to be beneficial to cognitive function of PWMSD; this is consistent with the findings of previous systematic reviews [15-17,23].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the efficacy of NPI only in PWMSD. However, the current study had several limitations. First, the certainty of evidence drawn from the current study was medium to very low, and publication bias could not be tested due to the limited number of studies included in the meta-analyses. We included the studies that diagnosed dementia using formal diagnostic criteria and provided the severity of dementia using validated measures in the current meta-analysis. Many studies did not specify the diagnostic criteria for dementia and/or the severity of dementia. Second, we employed fixed-effect models [29] for the following reasons: 1) the number of studies integrated into the analysis was too small to estimate the between-study variance, 2) study populations included in the current study were more homogenous than those included in previous meta-analyses, because we included populations with moderate to severe dementia only, and 3) the aim of the current study was to examine the overall effect of NPI. However, the heterogeneity between studies was still high in the current analysis.

CONCLUSION

Although the certainty of evidence was moderate or low, the current systematic review found that NPI had a beneficial effect on ADL and depression in PWMSD.

Acknowledgements

This systematic review was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Dementia of Korea [grant no. NIDR-1703-0018], and the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea [grant no. HI09C1379 (A092077)]. Also, this work was supported by KyungPook National University IACT grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Humancare Contents Dvelopment).

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

RN, YJK, and KWK created the search strategy and performed the search. RN, JY, and YY independently extracted relevant data from articles and assessed the methodological quality and RoB of the studies. YJK, SB, KWK and KK interpreted the data and judged included studies and theirs RoB. RN and KK drafted the manuscript, and KWK revised the manuscript content. KK supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.