Short-Term Psychiatric Rehabilitation in Major Depressive and Bipolar Disorders: Neuropsychological-Psychosocial Outcomes

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Our pilot study aims to investigate the efficacy of a Short-Term (4 weeks) Psychiatric Rehabilitation Program (S-T PsyRP), without specific cognitive remediation trainings, on the neuropsychological performance and psychosocial functioning of inpatients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or Bipolar Disorder (BD). Published studies with similar aims are lacking.

Methods

Fifty-three inpatients with MDD and 27 with BD (type I/II) were included. The S-T PsyRP was usually performed as clinical practice at Villa San Benedetto Menni Hospital and included a variety of activities aimed at promoting personal autonomies, interpersonal/social skills, and self-care. At the beginning and the end of the hospitalization we evaluated: neuropsychological performance (cognitive tests on verbal/visual working memory, attention, visual-constructive ability, language fluency, and comprehension); psychosocial functioning by the Rehabilitation Areas Form (RAF, handbook VADO); illness severity by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Repeated-measure ANOVA and Pearson's linear correlation were used.

Results

We found significant improvement (p<0.01) in all the neuropsychological tests except for one, in 4 out of 6 RAF psychosocial areas (“involvement in ward activities”, “autonomies”, “self-care”, and “self-management of health”) and in clinical symptoms severity. No associations were found between the amelioration of clinical symptoms and neuropsychological or psychosocial improvement.

Conclusion

A S-T PsyRP without specific cognitive remediation trainings may improve several cognitive/functional domains in MDD or BD inpatients, probably by offering opportunities to engage in demanding problem-solving conditions and cognitively stimulating activities.

INTRODUCTION

Psychiatric Rehabilitation (PsyR) is a field of clinical practice promoting the recovery and full integration in the community of persons with serious mental illness, in accordance to their strengths and preferences and with the least amount of professional support.1

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Bipolar Disorder (BD) are often associated with widespread impairment in several domains of life functioning. Poor performance relative to household/work and low quality of familial/social relationships is commonly reported in these populations, with a decline of their subjective quality of life.234 The daily life functioning of subjects with MDD or BD after symptom remission often remains impaired, suggesting that other determinants, such as neuropsychological deficits, may contribute to their functional decline.56 An impairment on a range of cognitive domains is well-documented in patients with MDD or BD, both in acute phases and euthymia.578 In these patients, long-lasting difficulties in daily life functioning has been associated with their long-lasting cognitive impairment,69 and neuropsychological functioning was the single best predictor of later socio-occupational outcome among young patients suffering from MDD or BD.10

Considering the relevance of functional impairment in these populations, a variety of psychosocial interventions in the framework of the PsyR has been applied as adjunctive treatments to pharmacological therapies. Most of them usually lasts several weeks or months and produces significant improvements in clinical and functional outcomes.1112 Recently, some findings have suggested that specific cognitive remediation trainings may improve neuropsychological and occupational/psychosocial functioning of subjects with MDD or BD.131415 No published studies investigated whether brief rehabilitative interventions lasting less than five weeks might be effective in subjects with MDD or BD and whether rehabilitative interventions that do not include specific cognitive remediation trainings might improve neuropsychological functioning in these clinical populations. Previous findings in schizophrenia showed how a psychiatric rehabilitation program without specific cognitive remediation significant improved cognitive functioning,16 as well as how living in group housing rather than in socially isolated housing showed positive effects on neurocognition in a mixed group of seriously mentally ill persons (schizophrenia, MDD, BD).17

Our pilot study aims is to investigate the efficacy of a Short-Term (4 weeks) Psychiatric Rehabilitation Program, without specific cognitive remediation trainings, on both neuropsychological performance and psychosocial functioning in a sample of inpatients suffering from MDD or BD. The PsyRP is performed as hospital clinical practice at Villa San Benedetto Menni Hospital. We hypothesize that it would improve both neuropsychological and psychosocial functioning of these patients.

METHODS

Participants

Eighty subjects with DSM-IV-defined18 MDD (n=53) or BD (Type I/II, n=27) who were in a depressive episode, without suicide risk, were included. They were recruited from the inpatients consecutively referring to Villa San Benedetto Menni Hospital to undergo a 4-week hospitalization for a Short-Term Psychiatric Rehabilitation Program (S-T PsyRP).

Inclusion criteria were: impaired (score 0 or 1) or borderline performance (score 2) in at least one neuropsychological test; score less than or equal to 6 (6=moderate difficulties) in at least one among the 19 domains of psychosocial functioning considered in this study, evaluated by the Rehabilitative Areas Form (see section “Assessment”). Exclusion criteria were: relevant modifications of pharmacological treatment within the 4 weeks preceding hospitalization or during the hospitalization, including addition or discontinuation of drugs; any modification of dosage of the drugs in use that might influence the neuropsychological performances, according to the concordant clinical judgment of 2 psychiatrists expert in both psychopharmacology and neuropsychology; other concurrent Axis-I diagnoses (DSM-IV criteria); suspected or diagnosed (QI<70) mental retardation; electroconvulsive therapy in the preceding 6 months; life-time neurological diseases; history of neurological trauma resulting in loss of consciousness; drug or alcohol abuse/dependence within the previous 6 months; hypo- or hyperthyroidism.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Inter-Company Ethics Committee of the Provinces of Lecco, Como and Sondrio, Italy. All the participants voluntarily provided informed consent to participate.

Procedure and measures

Both at the beginning (within the first three days) and at the end (the day before discharge) of the hospitalization, as part of the usual clinical practice, we provided a neuropsychological, a psychosocial functioning and a psychometric assessment.

Neuropsychological assessment

Trained psychologists administered the standardized neuropsychological battery described below both at the beginning and at the end of the hospitalization. The psychologist administering the battery at the end of the hospitalization was blind to the results obtained by each patient at the beginning of the hospitalization.

- Novelli's Story Recall Test:19 short- and long-term verbal memory.

- Attentional Matrices:20 ability to maintain attention over time and spot specific elements among distracters.

- Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Copy Test (ROCF-C):21 ability of disposing and organizing visual elements in the space and maintaining spatial relations among them (visual-constructive ability).

- The Rey-Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Recall Test (ROCF-R):21 long-term visual-constructive memory.

- Phonemic Fluency Test:19 language fluency, such as ability to recall words given a phonemic cue, and frontal executive functions, such as working memory.

- Semantic Fluency Test:19 language fluency, such as ability to recall words given a semantic cue.

- Token Test:20 ability to understand and process semantic information.

The neuropsychological battery took approximately 45 minutes. The results were expressed as scores corrected for age, schooling, and, when appropriate, gender, according to the Italian validation samples.20 The higher the score, the better the performance. In order to select the subjects suitable for this study, according to the inclusion criteria, the results of the battery at the beginning of the hospitalization were also expressed as equivalent scores derived from the corrected scores: 4,3=adequate performance; 2=borderline performance; 1,0=impaired performance.20

Psychosocial functioning assessment

The psychosocial functioning assessment of each subject was performed by trained clinical social workers.

At the beginning of the hospitalization they collected data covering the 28 domains of patients' functioning indicated in the Rehabilitation Areas Form (RAF). RAF is a clinical tool contained in the handbook VADO (Valutazione delle Abilità e Definizione degli Obiettivi–in English: Skills Assessment and Definition of Goals), a short manual for the planning and evaluation of rehabilitative interventions22 widely used in psychiatric facilities.23 The score of each domain ranges on a 7-point scale, from 9=excellent functioning to 3=extremely severe impairment. The RAF is considered a useful tool to assess functional domains where rehabilitation may be desirable and to define the specific goals of each individual rehabilitative program.24

At the end of the hospitalization the clinical social workers re-assigned scores to the 19 domains selected among the 28 of the RAF, namely those suitable to be revaluated after a short-term rehabilitative intervention in a hospital setting.

For the aim of this study, we considered only these 19 domains, both at the beginning and at the end of the hospitalization, and subdivided them into 6 areas evaluating different functions, on the basis of the instructions supplied in the VADO manual: degree of involvement in the ward activities (free-access activities and meals attendance); Socio-affective area (affective behaviors, supportive relationships, friendship); Aggressiveness (observance of the cohabitation rules, anger control); Autonomies (quantity and quality of daily activities, psychomotor speed, interests, level of general information, money management, use of transportation, phone use); Self-care (care of personal hygiene, clothing); Self-management of health (active interest towards personal physical and mental health).

Finally, at the end of the 4-weeks of hospitalization, the clinical social workers evaluated for each subject the degree of participation in the rehabilitation activities (VADO, Observational Form, 4-point scale: 0=insufficient, 1=sufficient, 2=good, 3=not assessable).

The Short-Term Psychiatric Rehabilitation Program

Each subject was involved in a personalized S-T (4 weeks) PsyRP, according to the usual clinical practice of Villa San Benedetto Menni Hospital. The S-T PsyRP was aimed at promoting personal autonomies, interpersonal/social skills, awareness and self-care of mental and physical health.27

At the beginning of the hospitalization, a team consisting of a psychiatrist, a psychologist and clinical social workers defined a personalized program for each subject on the basis of the clinical symptom severity, the psychosocial functioning and the neuropsychological performance highlighted by the assessment battery, considering both disabilities and residual strengths. The personalized program included daily group rehabilitation activities managed by clinical social workers and, twice a week, an individual psychological intervention carried out by a trained psychologist, including psycho-educational and structured behavioral interventions. Each subject received an agenda of daily activities, with the aim to increase the sense of responsibility for the planned activity and to facilitate the compliance to the program. Finally, at the beginning of the program, patients were individually instructed on the importance of participation to the activities in order to improve efficacy of the S-T PsyRP.

The group rehabilitative activities included: training on daily activities (self-care, room management); social activities (group discussions, reading newspapers with comments, training on listening and communication group, outdoor experiences and brief trips); puzzle solving; art, pottery and singing workshops; stretching and relaxation activities.

Data analyses

Differences between continuous or nominal variables between the two groups at the beginning of hospitalization were respectively investigated by t-test or χ2 analysis.

Changes between the beginning and the end of the hospitalization were investigated by different factorial repeated-measure ANOVA's (time of assessment (admission/discharge)=within-subjects factor; diagnosis (MDD/BD)=between-subjects factor). The dependent variables were: 1) the corrected scores of the seven neuropsychological tests; in each of the seven ANOVA analyses we included only those subjects that, at the beginning of the hospitalization, had shown an equivalent score=0 or 1 or 2 in the neuropsychological test inserted in that model as dependent variable; 2) the scores of the six VADO areas; in each of the six ANOVA analyses we included only those subjects that, at the beginning of the hospitalization, had shown a score less-than or equal to 6 in the VADO area inserted in that model as dependent variable; 3) the BPRS scores.

Associations between the changes of the variables were investigated by Pearson's linear correlations with the delta scores (scores at discharge–scores at admission) of the BPRS, the seven neuropsychological tests and the six VADO areas. The level of statistical significance considered in the analysis was α=0.01. The Statistical Package for Windows (Statistica 10.0, Statsoft Inc, Tulsa, Oklahoma) was used.

RESULTS

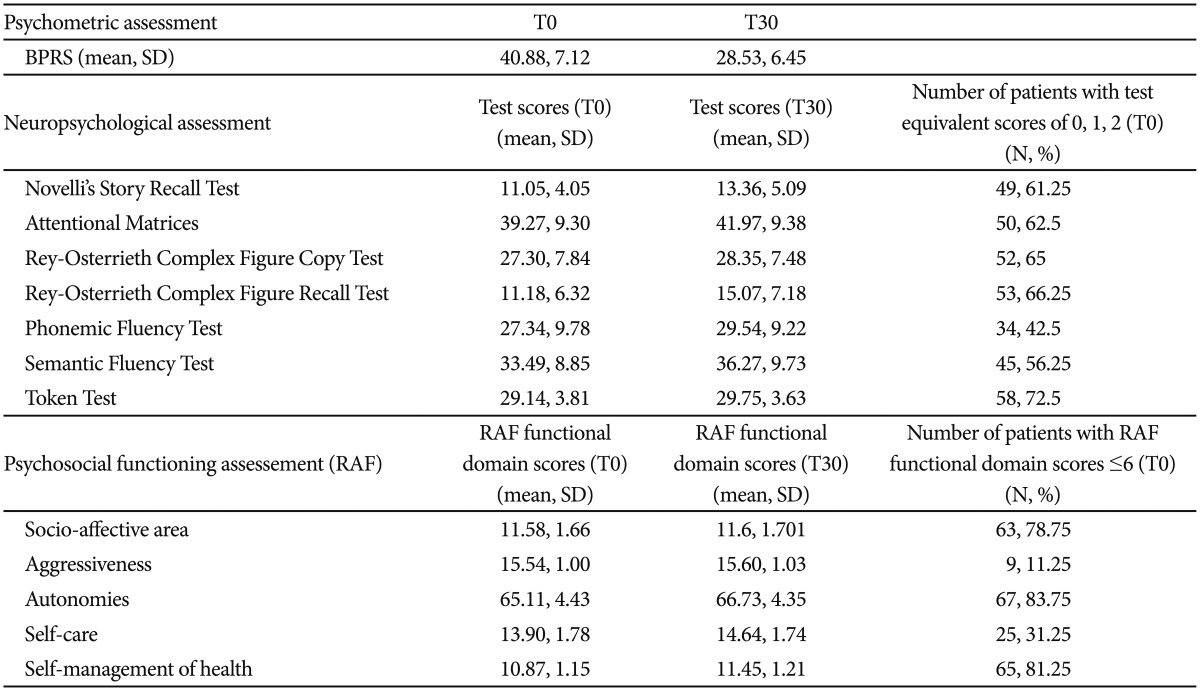

The sample included 80 subjects (60 female and 20 male), 53 out of them with MDD and 27 with BD. The mean age of the sample was 58.32±12.10 years (range: 32–77 years) and the mean years of education were 9.53±4.01 years. Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1. The subjects with MDD did not significantly differ from those with BD in gender distribution, age, education, or clinical severity, neuropsychological and psychosocial functioning at the beginning of the hospitalization (data not shown). All subjects showed a sufficient or good degree of participation in the rehabilitation activities.

Between the beginning and the end of the hospitalization, we found significant improvement in all the neuropsychological tests, except the Token Test, in 4 areas of the RAF and in severity of clinical symptoms (Table 2). No effects of interaction “time” X “diagnosis” were found in all these analyses (Table 2).

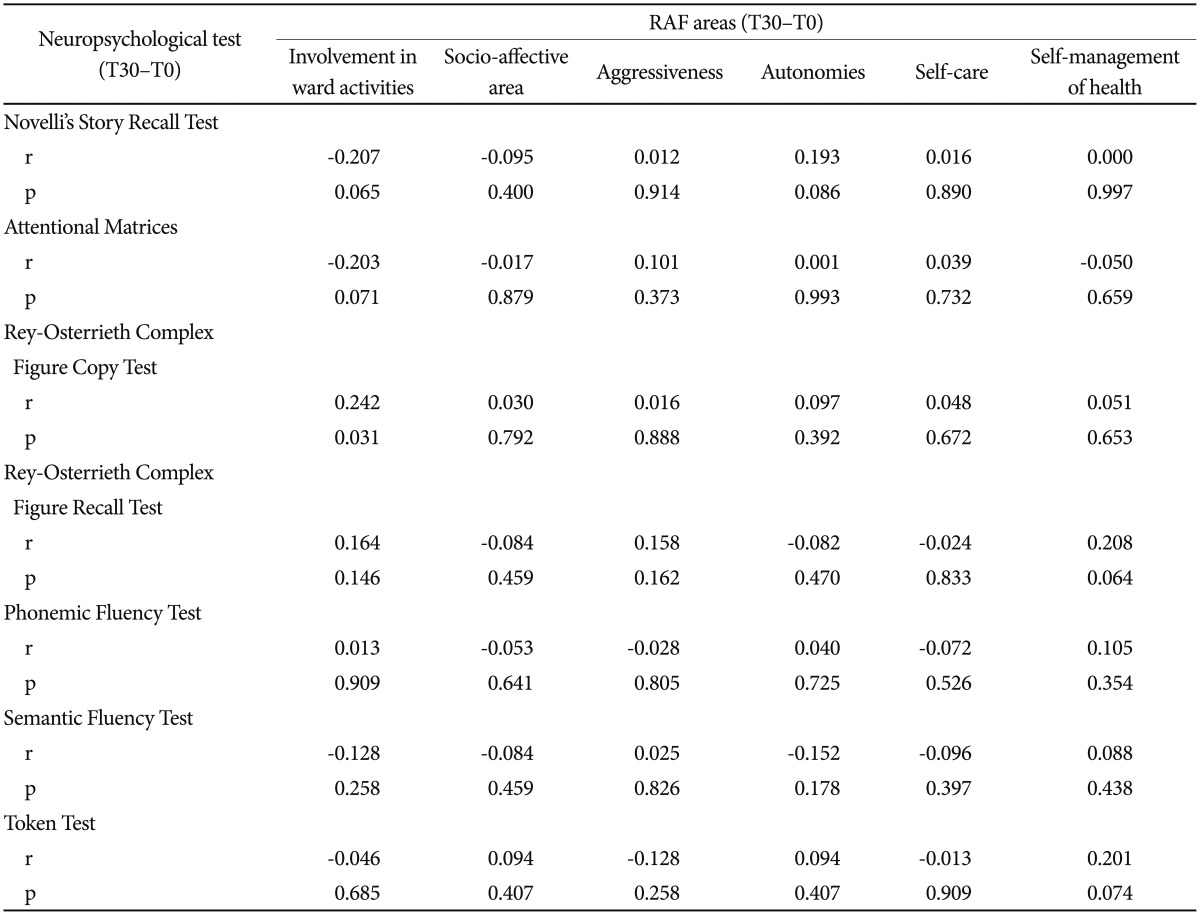

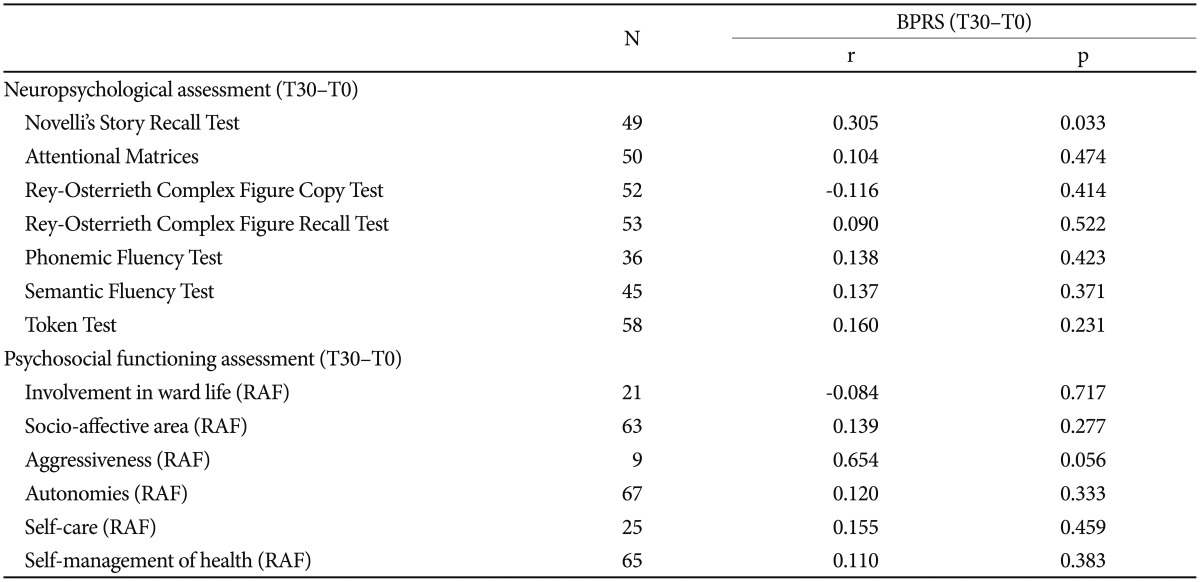

No correlations were found between the changes of the BPRS during the hospitalization and the changes of the neuropsychological tests or the RAF areas scores (Table 3). No correlations were found between the changes of the neuropsychological tests scores and the changes of the RAF areas scores (Table 4).

Association between changes of clinical symptoms and changes of neuropsychological or psychosocial functioning

DISCUSSION

In line with our hypothesis, we found that the S-T (4 weeks) PsyRP without specific cognitive remediation trainings usually performed as clinical practice at Villa San Benedetto Menni Hospital significantly improved both neuropsychological performance and psychosocial functioning in a sample of inpatients suffering from MDD or BD. A significant decrease of symptom severity was also found, but without significant associations with the improvement of neuropsychological performance or psychosocial functioning. This suggested that the amelioration of clinical symptoms did not explain the neuropsychological or psychosocial improvement. Our results should be considered preliminary since the sample size is small and, to the best of our knowledge, published studies with similar aims in MDD or BD are lacking. The main limitation of our study is the observational design without a comparison group that did not receive psychiatric rehabilitation. Without this, it cannot be excluded that the observed cognitive improvement may be related to other factors, such as spontaneous recovery, passage of time, other aspects of the hospital environment, medication effects, increased socialization. Thus, our results should be interpreted with caution and future randomized controlled studies with larger samples are needed to draw reliable conclusions.

Neuropsychological outcome

At the beginning of the hospitalization, our sample showed impairment in several neuropsychological domains, including verbal memory, attention, visual-constructive ability and memory, language fluency, working memory, and ability to process semantic information, as previously found.578 At the end of the hospitalization, a significant improvement was found in all the neuropsychological domains, except the ability to understand and process semantic information (Token Test), without differences between subjects with MDD or BD. Our findings suggested that also a rehabilitative program without specific cognitive remediation trainings may contribute to the improvement of neuropsychological functioning, probably by offering opportunities to engage in demanding problem-solving conditions and cognitively stimulating activities. Indeed, our results are in line with previous studies in different populations, showing that common leisure and social activities may enhance a variety of cognitive functions, likely by stimulating brain regions involved in information processing, memory, attention, learning, planning and visual-constructive processes. The frequency of participation in leisure activities in old age has been previously associated with improvement of verbal and working memory, perceptual speed and cognitive reserve,2829 and with reduced risk of incident Alzheimer Disease28 or Mild Cognitive Impairment.30 Musical activities, that involve a wide bilateral network of brain areas related to attention, semantic processing, memory and learning,31 are proved to enhance cognitive functions both in healthy subjects32 and in dyslexia,33 dementia34 and recovery from stroke.31 Group reading activities have been reported to improve cognitive and psychosocial functioning in hospitalized patients with psychosis35 and group conversation, art/drama sessions and recreational activities have been shown to ameliorate the neuropsychological performance in schizophrenic patients.36

We found no effects of rehabilitation on the understanding and processing of semantic information. Since the Token Test requires also efficient attentional shifting and executive functions to be efficiently performed, we cannot exclude that deficits in these abilities, not assessed by our neuropsychological battery, might have masked potential effects of the rehabilitative activities on the comprehension ability tout-court. We cannot also exclude that, if compared to the other neuropsychological measures, the Token Test may have lower discriminating power and it would be less sensitive to change. Further studies with more comprehensive batteries will be useful to better disentangle the different cognitive domains.

Psychosocial outcome

At the beginning of the hospitalization, our sample showed impairment in several psychosocial areas, as reported in other studies.23

At the end of the hospitalization, a significant improvement was found in the degree of involvement in the ward activities, autonomy, self-care and self-management of health, consistently with the global purpose of our rehabilitative program. No differences were found between subjects with MDD or BD. The improvement of psychosocial functioning was not associated to the amelioration of clinical symptoms, although we cannot exclude that an increase of patients' well-being may have positively influenced their general psychosocial functioning. Our findings are similar to those previously found with long lasting rehabilitative programs in subjects with MDD or BD,1237 suggesting that also short-term rehabilitative interventions may be considered valuable tools to improve psychosocial functioning in these populations.

We found no significant effects of rehabilitation on aggressiveness and socio-affective areas. Some reasons may explain these results. The number of subjects showing difficulties in managing aggressiveness at the beginning of the hospitalization was very small, thus masking potential beneficial effects of rehabilitation that should be investigated in larger samples. On the other hand, this result may suggest the need of including adjunctive interventions specifically targeted at patients with difficulties in managing aggressiveness. The socio-affective area encompasses aspects that may be only partially evaluable in a hospital setting. Indeed, although social and supportive relationships may be displayed also in a hospital setting, affective behaviors or friendship are fully expressed only in real daily life, thus hiding potential effects of our rehabilitation program on this area. Further studies evaluating socio-affective behaviors in the real life after the discharge from hospital may provide more reliable results.

Finally, we did not find associations between improvement of psychosocial functioning and amelioration of neuropsychological performance. Some factors may explain this result. The sample size might be too small to find this association. The improvement of cognitive functioning may require more than 4 weeks to be generalized to psychosocial functioning, thus additional follow-up evaluations after discharge are needed to clarify this relationship. On the other hand, in previous studies the strongest associations between cognitive and psychosocial abilities were found when objective indicators of real world functioning were used, such as employment, independent living, marriage/equivalent long-term relationships.691013 Since these outcomes were not evaluable in our study, future longitudinal studies with more specific indicators of real world functioning are needed.

Our study has several limitations in addition to those previously discussed. The psychosocial functioning assessment at the beginning and the end of the hospitalization was performed by the same clinical social workers, thus biases cannot be excluded. Since the program encompassed a variety of activities, we cannot disentangle their potential different effects or test whether some activities may be more suitable for certain patients than for others, according to their individual/clinical characteristics. All the patients were in depressive phase and hospitalized to undergo the rehabilitation program, thus our results may be not generalizable to patients in different clinical conditions/severity. Although we excluded from the study patients who underwent relevant modifications of their pharmacologic treatments, we cannot exclude an influence of pharmacotherapy on our results, related to the potential effects of psychotropic medications on cognitive performance or general well-being of the patients.3839 Finally, the lack of follow up after the discharge did not allow us to investigate whether the neuropsychological and/or psychosocial improvements were maintained over time.

In conclusion, our preliminary study found that our S-T PsyRP may promote a significant amelioration of both neuropsychological and psychosocial functioning in inpatients with MDD or BD in depressive phase. This suggested that also a general rehabilitative intervention lasting a few weeks and without specific cognitive remediation trainings may exert relevant effects on several cognitive and functional domains. This intervention may be a valuable tool in hospital clinical practice for these psychiatric populations. Randomized controlled studies are needed to confirm our preliminary results.