Are Tattoos an Indicator of Severity of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Behavior in Adolescents?

Article information

Abstract

Objective

To compare adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury behavior and tattoos [NSSI (T+)] with another group with non-suicidal self-injury behavior without tattoos [NSSI (T-)].

Methods

Adolescents (n=438) 42.6% males from the community (M=12.3, SD=1.3), completed the Self-Injury Schedule.

Results

The lifetime prevalence of tattoos performed with the purpose to feel pain was 1.8%. Compared to the NSSI (T-) group, the NSSI (T+) group was significantly more likely to meet the DSM-5 frequency criteria of 5 self-injury events in 1 year, practice more than one method of self-injury, and topography, more suicidal intentionality, more negative thoughts and affective emotions before, during, and after self-injury and more academic and social dysfunction.

Conclusion

Adolescents from the community who practice tattooing to feel pain, show a distinct phenotype of NSSI. Health professionals and pediatricians should assess tattooing characteristics such as intention (to feel pain), frequency, and presence of non-suicidal self-injury behavior and suicide intentionality.

INTRODUCTION

Prevalence of tattooing in the general population it is between 6% to 24% [1], in clinical samples of adolescents it is between 4.5% and 13.2% [2-5], the highest figures are reported in young adults, and militia-related individuals [5,6].

Recent studies show an association between tattooing and psychiatric disorders, such as depression [7] anxiety, eating disorders [5] and risky behaviors like substance use [5,8-12], promiscuity [11,13], suicidal thinking and attempted suicide [5,7,9,14,15].

Adult tattoo users report self-injury behavior more frequently [16,17], sharing psychological precipitants such as negative thoughts of anxiety, tension, anger, distress or depression and interpersonal difficulties before the act [16,18]. These association has been poorly studied in adolescents, although, research suggests those who acquire permanent tattoos during adolescence, specially at earlier ages (11–16 years), have more risk factors for psychopathology and other negative outcomes and engage more frequently in risky behaviors [4,5,9,19,20].

Tattoos and piercings have been considered as methods of self-harm, but, they may have social acceptance in some cultures [21,22]; this explains why under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5) [23], tattoos were excluded from the non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) condition, specifically mentioned in criterion D: “Behavior (self-injury) is not socially accepted (as an example, piercings, tattoos, part of a religious or cultural ritual...).”

The aim of this study was to compare the characteristics of NSSI behavior with and without tattoos performed with the intention to feel pain in a sample of Mexican adolescents.

The Research and Ethics Committee of the participating institutions approved the study (II1/01/1013).

Hypothesis

If the presence of tattoos is associated with risky behaviors in adolescents, then, adolescents who tattoo themselves with the intention to feel pain and practice NSSI will injure more often, in more anatomical sites, experience more negative feelings and cognitive states and greater dysfunction.

METHODS

A survey with a cross-sectional and comparative design was conducted involving adolescents (n=438) between 11 and 17 years of age, with a mean age of 12.3 years (SD 1.3), 57.2% were female (n=251).

Instruments

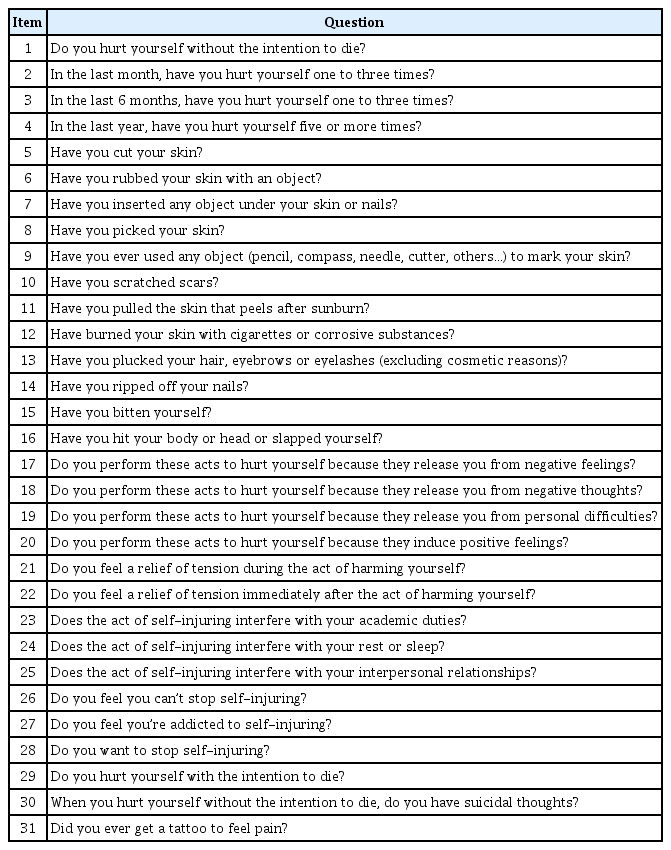

The Non-Suicide Self-Injury Schedule (NSSI-S) [24]

The instrument is based on the DSM-5 criteria for NSSI, it contains 31 dichotomous items with a yes/no response format to explore the DSM-5 dimensions of self-injuring: B1: Psychological precipitants, B2: Concerns, B3: Urgencies, B4: Contingent responses, C1: Interpersonal difficulties, C2: Preoccupation with the behavior, C3: Frequent thoughts about self-injuring, E: Impairment and some explanatory variables. The frequency of self-injuring according to DSM-5 Criteria; the methods and topography; the emotions present before, during and after self-injuring; the associated addictive component; the triggering and mitigating factors for self-injuring; the suicidal intentionality and the age of onset of the behavior.

Cases were assigned to two groups if they gave a positive answer to item 1: “Do you hurt yourself without the intention to die?” and answered yes/no to item 31: “Did you ever get a tattoo to feel pain?” Group 1) students with non-suicidal self-injury and tattoos with the intention to feel pain [NSSI (T+)] and group 2) students with non-suicidal self-injury without tattoos [NSSI (T-)].

Procedure

After obtaining approval from administrators of two public high schools and parents, those who agreed to participate signed an informed consent. Students gave their assent and completed the instrument in their classrooms. All participants received information on how to seek attention in our institution.

Statistical analysis

Categorical demographic variables were analyzed using frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were analyzed using the Student t-test. The chi-square or Fisher test was used for categorical variables and unadjusted odds ratios were calculated to measure the effect size of the association between practicing non-suicidal self-injury behavior and tattoos to feel pain (yes/no) and the rest of the variables of the NSSI-S. A statistical significance level of p=0.05 was established.

An algorithm was used to perform the statistical analysis used in this study as follows: Dimension A explores the methods used for self-injury through items 5–16. The higher the score, the more serious the self-harmful behavior. The 12 items were added, and a new binary variable was created recoding to 0= those who do not injure themselves and 1= those who injured themselves with one or more methods. Items 2–4 inquire about frequency according to DSM-5 criteria.

Dimension B evaluates the contingent response through items 17–22, which were added, and a new binary variable was recoded assigning to 0 those with no feelings or cognitive states and 1 to those presenting one or more negative feeling or cognition.

Dimension C explores if the behavior is associated with at least one of the following: interpersonal difficulties or negative feelings or thoughts.

Criterion D was excluded for the purpose of this research.

Dimension E assesses social, school and daily living impairment in the school area, other activities of daily living (resting, sleeping) and in the social environment, through items 23–25; the items were added, and a new binary variable was recoded assigning a 0 to those who had no social, school and daily living dysfunction and 1 to those who had more than one.

RESULTS

The prevalence of NSSI was 11.5% (n=50), while 1.8% (n=8) reported having a tattoo performed with the intention to feel pain. The frequency of tattooing was larger in males compared to females (2.2% vs. 1.6%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

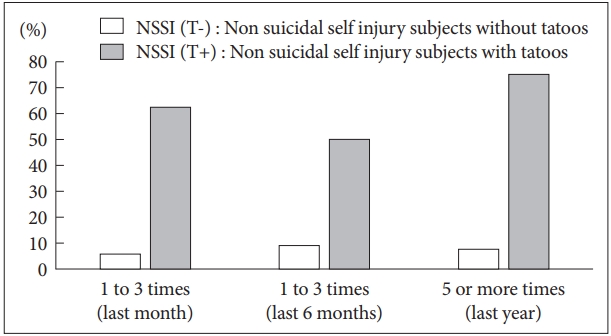

The presence of NSSI behavior was larger in students with tattoos (62.5%) than in adolescents without them (10.6%) (OR:14; 95% CI: 3.2–60.5; p=0.001), Figure 1 shows a comparison of the number of self-injuring events per month, 6 months and 12 months for each group.

The DSM-5 frequency criterion (5 events per year) was higher in the NSSI (T+) group compared to the NSSI (T-), 75% vs. 7.7% respectively (OR: 35.7; 95% CI: 6.9–184); in the last month, 62.5% vs. 6.1% (OR: 25.5; 95% CI: 5.7–112.9) and in the previous 6 months, 50% vs 9.4% (OR: 9.6; 95% CI: 2.3–40) (Figure 1).

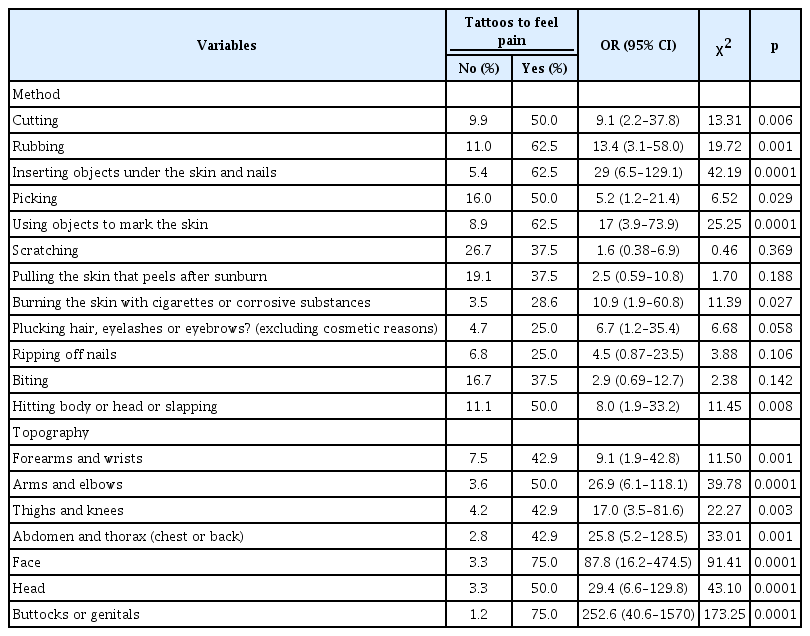

Table 1 shows the results of comparing the NSSI (T-) and NSSI (T+) groups according to the method and topography of self-injury.

Method of self-injury

The NSSI (T+) group was significantly more likely to practice all methods of self-injury, with the top three including sticking objects under the skin (OR: 29; 95% CI: 6.5–129.1), using objects to mark the skin or nails (OR: 17; 95% CI: 3.9–73.9) and rubbing the skin (OR: 13.4; 95% CI: 3.1–58%).

Topography

The NSSI (T+) group was significantly more likely to selfinjure in buttocks and/or genitals (OR: 252.6; 95% CI: 40.6–1570.1), face (OR: 87.8; 95% CI: 16.2–474.5), head (OR: 29.4; 95%CI: 6.6–129.8) and arms and elbows (OR: 26.9; 95% CI: 6.1–118.1).

DSM-5 criteria

Psychological precipitants

The results of the comparison between the NSSI (T-) and NSSI (T+) groups on psychological precipitants are reported in Table 2. Compared to the NSSI (T-) group, the NSSI (T+) group was significantly more likely to have negative emotional and cognitive states before, during, and after the selfinjury. The effect size was higher for feelings of anxiety (OR: 40.1; 95% CI: 7.4–217.0), self-criticism (OR: 38.2; 95% CI: 7.4–197.3) and tension (OR: 29.2; 95% CI: 6.5–129.8) before the behavior.

Addictive component

The NSSI (T+) group reported more addictive features, like feelings of addiction to self-injurious behavior (OR: 55.1; 95% CI: 10.0–303.7), being unable to stop doing the self-injurious act (OR: 8.7; 95% CI: 2.1–36.3) and desire to stop doing the self-injurious act (OR: 7.2; 95% CI: 1.5–33.1) (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the groups comparison between DSM-5 criteria for Dimension A, Dimension B (B1, B2 y B3), Dimension C (C1, C2, C3) and Dimension E.

Dimension A

Compared to the NSSI (T-) group, the NSSI (T+) self-injured more frequently (Dimension A) (OR: 7.9; 95% CI: 1.0–64.8).

Dimension B

The NSSI (T+) reported a larger percentage of contingent responses to self-jury (Dimension B), such as: Releasing negative feelings (B1) (OR: 15.2; 95% CI: 3.5–66), Resolving interpersonal difficulties (B2) (OR: 14.1; 95% CI: 3.3–59.5) and Induction of positive feelings (B3) (OR: 19; 95% CI: 4.1–88.1).

Dimension C

The NSSI (T+), had a larger percentage of negative emotions and cognitive states associated with NSSI, including interpersonal difficulties, negatives feelings or thoughts (OR: 33.8; 95% CI: 4.1–279.3), and preoccupation with the intended behavior that is difficult to control (OR:11.1, 95% CI: 2.6–46.3) (Tables 2 and 4).

Dimension E

The NSSI (T+), had more impairment (Dimension E) on Academic activities (OR: 95.3, 95% CI: 17.5–517.9), Interpersonal relationships (OR: 22.3; 95% CI: 4.7–105.4), and Rest and sleep (OR: 29.2; 95% CI: 6.6–128.9).

Suicidal intention

The NSSI (T+) group was more likely to self-injure without suicidal intent, 62.5% compared to 10.6% of the NSSI (T-) but also reported more suicidal thoughts during the self-injurious behavior, 50% vs 4.9% (OR: 19.2; 95% CI: 4.4–82.3). The majority of the NSSI (T+) had more suicidal intent (87.5%) when self-injuring compared to only 2.1% of the NSSI (T-) (OR: 323.5; 95% CI: 35.9–2911.0) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated differences in the characteristics of self-injury behavior in two groups of adolescents who practice self-harm with and without tattoos: NSSI (T+) and NSSI (T-). The lack of similar studies makes it hard to compare our results.

In our study, the frequency of tattoos with the intention to feel pain in the total sample was 1.8% which is similar to adolescents of the community from Chile (1.7%) and Taiwan (1%) [25,26]. Turkey and Canada reported a higher prevalence (4.8% and 7.9%) [4,10], but these studies assessed how frequently the participants got tattoos but not the motivating factors for getting tattooed.

In our study, the prevalence of tattoos performed to feel pain in adolescents with NSSI in the community was higher (10%); this figure approximates the prevalence in clinical samples, however, most of the studies included adults [2,3,27].

In our study, the frequency of tattoos by sex (male 2.2% vs. girls 1.6%) showed no significant differences, this result is consistent with other studies in the community and in clinical samples [4,10,17,20]. In contrast, other research shows increased frequency in females [9,11,28-32].

DSM-5 criteria

Dimension A

The NSSI (T+) group met the DSM-5 frequency criteria of 5 events per year proposed by Shaffer [33,34] which seems to identify individuals with more severe self-injury phenotypes. For example Dulit et al. [35], studied a large group of patients with borderline personality disorder and those who reported 5 self-injury events in one year were more likely to have another psychiatric disorder, these findings have been confirmed in later studies [36,37], but opposing results have also been reported by Muehlenkamp et al. [38], who, in a clinical study of adolescents, proposed raising the frequency threshold of the DSM-5 criteria arguing that 5 events per year over-pathologize the behavior, an opinion shared by other researchers [39,40]. Further research comparing clinical and community samples is necessary.

We also found that adolescents who performed tattoos to feel pain chose different methods of self-injury (inserting objects under the skin and nails, using objects to mark the skin, burning) compared to adolescents without tattoos who selfinjure (scratching, cutting, rubbing and picking the skin) reported by other researchers [41-44]. Similar results were reported by Iannaccone et al. [45], who found a high correlation between burns and tattoos in women with eating behavior disorder.

Topography

The NSSI (T+) group was more likely to self-injure in all parts of the body involving buttocks/genitals, face, and head. Contrasting with the NSSI(T-) group in which forearms and wrists were preferred body locations, which is consistent with other research [41,43,46,47].

Although research is lacking, clinical experience suggests that self-injuring in face, breasts, eyes, and genitals is of special concern because it implies a higher level of psychological distress [48].

Dimensions B and C

In comparison to the NSSI (T-) adolescents in the NSSI (T+) group met the majority of DSM-5 criteria included in dimension B. B1: Release of negative feelings or cognitions; B2: Resolution of interpersonal difficulties; B3: Induction of positive feelings. Likewise, concerning Dimension C, the NSSI (T+) group reported higher frequencies of negative thoughts and feelings; which is similar to the findings reported by Aizenman and Jensen [16], who found tattooed college students who also self-injure had higher depression, lower self-esteem and mastery/control scores.

Addictive component (Table 3)

Compared to the NSSI (T-) group, the NSSI (T+) showed a higher frequency of addictive component (10.2% vs. 50% respectively) which was investigated through items 26–28 (Table 6). This is congruent with previous clinical research where addictive features are present in 10–97% of adolescents who practice NSSI [49,50]; and also with a review by Bunderla and Gregorič [51], who reported 5 studies showing higher pain threshold and longer pain tolerance in NSSI subjects. These results are consistent with a study of young college students, where 48.5% reported addictive features to tattooing behavior [11].

Dimension E social dysfunction

It is difficult to contrast our results with the few studies that have investigated the DSM-5 criteria in adolescents with NSSI. Increased absenteeism and dropout rates among tattooed adolescents are common [2,3,9,15,51]. These findings support school dysfunction, however, in a Mexican with young adults, Benjet et al. [52] suggested that individuals may not perceive this behavior as dysfunctional because it is used as an effective strategy to deal with unpleasant feelings, cognitions and interpersonal or family difficulties. In our sample, impairment was less frequent among those who self-injure without tattoos (18.3% compared to 39.9 of the Mexican sample of young adults) [52]. These differences could suggest adolescents have less awareness or normalize the behavior due to peer pressure or a desire for group integration. As Benjet et al. [52] points out, low perception of impairment is an obstacle for seeking treatment.

Severity indicators

Compared to the NSSI (T-) group, the NSSI (T+) group presented other indicators of self- injury severity, such as using more than one method, more anatomical sites, more frequent events and a greater propensity to suicide intent (87.5%); this is consistent with other studies that show teens and young adults with tattoos are at increased risk of suicide attempts and unhealthy practices [5,7,9,18,26,32,53,54]. However, the evidence is conflicting because other authors do not report this association [11,55]. Some researchers show tattoos could be a protective or mitigating factor for suicidal ideation and attempts [27]. Moreover, there is evidence of a decline and extinction of self-injurious behavior after tattooing [18] and most tattooed teens do not harm themselves, only 33% show selfinjury practices [8]. More research is needed to better characterize which individuals are more prone to engaging in suicidal behavior and other risk factors.

We also found that a high percentage of tattooed adolescents with NSSI have more suicide intent suggesting that suicide intent and NSSI are overlapping and therefore extremely difficult to differentiate due to its alternating nature, this explains why studies show that adolescents with NSSI are at higher risk of suicide [56].

The significance of our results is that health personnel and adults involved with the care of children and adolescents with tattoos should intentionally inquire about self-injurious behavior, and if present, investigate about risk behavior such as low academic achievement, unprotected sex, substance abuse, promiscuity, eating disorders, accidents and suicidal intent [4,5,9,15,18,45,54].

Limitations

The presence of tattoos was investigated through self- report and no visual confirmation was performed as some studies have done in clinical samples where the context is adequate for a physical examination.

We did not ask if the teenagers had requested permission from their parents prior to the tattooing process. There is evidence that around 83% of adolescents do not have permission from their parents to obtain a tattoo [57].

In Mexico, the practice of tattooing is prohibited in minors under 18 years of age, unless they are accompanied by their parents or guardians; after signing an informed consent letter, and a prior sanitary questionnaire and letter of authorization are completed [38]. Some studies show that more than 60% of adolescents do not ask their parents for permission to get a tattoo [27,57,58], although others report opposite findings [2,51] this is important because adolescents who do not ask for permission could also engage in more risky behavior than their peers who do not get tattoos or do so with proper authorization. Also, our small sample size precludes us from analyzing adolescents who tattoo themselves without the intention to feel pain and who engage in NSSI.

Conclusions

Our results support the idea that tattoos performed for feeling pain are a correlate of non-suicidal self-injury behavior, since they share DSM-5 characteristics, as frequency, and greater severity in most of variables. Hence the importance of asking the purpose behind getting a tattoo, whether they practice self-harm and assessing suicidal intentionality. Our findings also suggest that a group of individuals could engage in tattooing as a form of NSSI and further research could warrant adding a specifier in Diagnostic Criteria.

Acknowledgements

We the authors are grateful to all the families who participated in this study.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Lilia Albores-Gallo. Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology: Marco Antonio Solís-Bravo, Yassel FloresRodríguez, Liliana Guadalupe Tapia-Guillen, Aymara Gatica-Hernández, Miriam Guzmán-Reséndiz, Lilia Albores-Gallo. Project administration: Lilia Albores-Gallo. Writing—original draft: Marco Antonio Solís-Bravo, Yassel Flores-Rodríguez, Liliana Guadalupe Tapia-Guillen. Writing—review & editing: Aymara Gatica-Hernández, Miriam Guzmán-Reséndiz, Luis Alberto Salinas-Torres, Tania Lucila Vargas-Rizo.