Anhedonia and Dysphoria Are Differentially Associated with the Risk of Dementia in the Cognitively Normal Elderly Individuals: A Prospective Cohort Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

We investigated the impact of depressed mood (dysphoria) and loss of interest or pleasure (anhedonia)on the risk of dementia in cognitively-normal elderly individuals.

Methods

This study included 2,685 cognitively-normal elderly individuals who completed the baseline and 4-year follow-up assessments of the Korean Longitudinal Study on Cognitive Aging and Dementia. We ascertained the presence of dysphoria and anhedonia using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory. We defined subjective cognitive decline as the presence of subjective cognitive complaints without objective cognitive impairments. We analyzed the association of dysphoria and anhedonia with the risk of cognitive disorders using multinomial logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, education, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale score, Apolipoprotein E genotype, and neuropsychological test performance.

Results

During the 4-year follow-up period, anhedonia was associated with an approximately twofold higher risk of mild cognitive impairment (OR=2.09, 95% CI=1.20–3.64, p=0.008) and fivefold higher risk of dementia (OR=5.07, 95% CI=1.44–17.92, p=0.012) but was not associated with the risk of subjective cognitive decline. In contrast, dysphoria was associated with an approximately twofold higher risk of subjective cognitive decline (OR=2.06, 95% CI=1.33–3.19, p=0.001) and 1.7-fold higher risk of mild cognitive impairment (OR=1.75, 95% CI=1.00–3.05, p=0.048) but was not associated with the risk of dementia.

Conclusion

Anhedonia, but not dysphoria, is a risk factor of dementia in cognitively-normal elderly individuals.

INTRODUCTION

Although the association between depression and the risk of dementia has been reported in many previous cross-sectional and prospective studies [1], it was not replicated in some studies [2,3] and its underlying mechanisms remain controversial. Depression may represent a risk factor of dementia [4,5], a prodromal symptom of dementia [6-10], a reaction to the symptoms of dementia [11], or a comorbid disorder that shares common pathophysiology with dementia [1,12].

To diagnose major or minor depressive disorders, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) requires one of two core symptoms to be present; being depressed or sad (hereafter dysphoria) and having markedly decreased interest or pleasure (hereafter anhedonia) [13]. Although anhedonia is less recognized than dysphoria and often misunderstood as a part of aging process [14], it is more prevalent than dysphoria [15,16], and plays an increasingly important role in the presentation of depression in older adults [17-21]. Furthermore, anhedonia is a key symptom of apathy [22]. Apathy has been repeatedly identified as an early symptom linked to clinical progression in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [23], and was associated with the hypometabolism of posterior cingulate cortex [24]. In our previous prospective study, anhedonia, but not dysphoria, was associated with the risk of AD conversion in people with MCI [25].

A recent study showed that apathy-anhedonia was associated with the neurodegeneration of brain regions related to AD in cognitively normal older adults [26]. However, to our knowledge, whether dysphoria or anhedonia is associated with future risk of cognitive decline in cognitively-normal elderly individuals has not been investigated. In this community-based prospective cohort study, we investigated the differential impact of dysphoria and anhedonia on the risk of cognitive decline in the older adults with normal cognition.

METHODS

Subjects

This study was conducted as a part of the Korean Longitudinal Study on Cognitive Aging and Dementia (KLOSCAD) [27]. The KLOSCAD is a nationwide population-based prospective cohort study with elderly Koreans launched in November 2009. In the KLOSCAD, 6,818 individuals who were randomly sampled from residential rosters of 13 districts of Korea, were aged 60 or older, and spoke Korean participated in the baseline assessment and have been followed since then every 2 years.

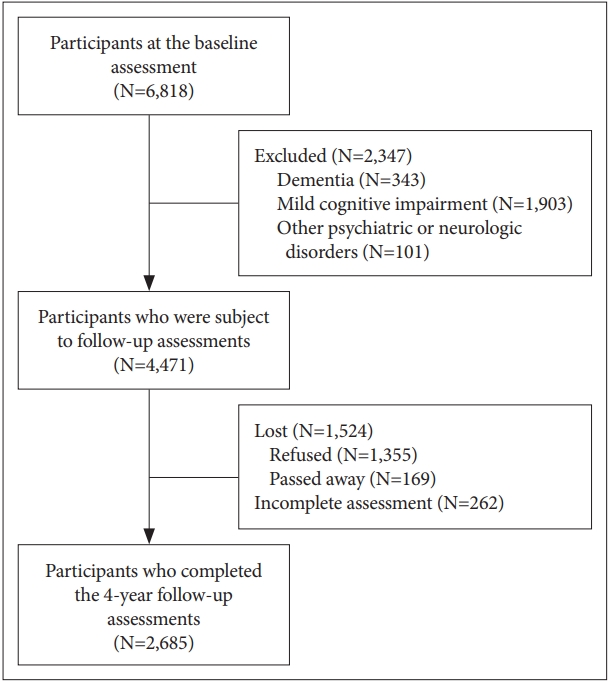

In the current study, we included 4,471 cognitively-normal elderly individuals after excluding 101 participants with Axis I disorders listed in the DSM-IV [13] or neurologic disorders that could affect their cognitive function. Of them, 2,685 completed the 4-year follow-up assessments (Figure 1). The non-responders to the follow-up assessment were older (p<0.001) and less educated (p<0.001), had higher Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score (p=0.028) and lower Korean version of Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD-K) Neuropsychological Assessment Battery total score (CERAD-TS, p<0.001), and showed more dysphoria (p<0.001) and anhedonia (p<0.001) than the responders. However, sex and the presence of the APOE e4 allele were not significantly different between the two groups.

Study flowchart. At the baseline assessment, 6,818 individuals participated. We excluded participants who were diagnosed with dementia (N=343), mild cognitive impairment (N=1,903), and 101 participants with other psychiatric or neurologic disorders (N=2,347). Among them 1,355 participants refused follow up assessment, 169 passed away before follow up, and 262 had incomplete assessment. A total of 2,685 participants completed the 4-year follow-up assessment.

All participants provided written informed consent. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (B-0912-089-010).

Assessments

Geriatric neuropsychiatrists with expertise in dementia research administered a face-to-face standardized diagnostic interview, neurological and physical examinations, and laboratory tests using the CERAD-K Clinical Assessment Battery [28] and the Korean version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI-K) [29]. They also evaluated comorbid medical conditions using the CIRS [30,31]. Research neuropsychologists administered the CERAD-K Neuropsychological Assessment Battery, Lexical Fluency Test [32], and Digit Span Test [33] to the subjects, to collect baseline and follow-up data. The CERADK-N consists of nine neuropsychological subtests, including the Categorical Fluency Test, the modified Boston Naming Test, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), the Word List Memory Test, the Constructional Praxis Test, the Word List Recall Test, the Word List Recognition Test, the Constructional Recall Test, and the Trail Making Test A. We obtained the CERAD-TS by summing the scores of the subtests of the CERAD-K Neuropsychological Assessment Battery except for the MMSE, Constructional Praxis Test, and Constructional Recall Test [34].

We defined the presence of subjective cognitive complaints based on the clinical judgement of research geropsychiatrists. We ascertained the presence of objective cognitive impairment if a subject scored worse than -1.5 standard deviations (SD) on the age-, sex-, and education-adjusted norms for Korean elderly individuals on any of the 11 neuropsychological tests. We diagnosed dementia according to the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria [13] and MCI according to the consensus criteria proposed by the International Working Group on MCI [35,36]. We categorized the subjects who had subjective cognitive complaints but no objective cognitive impairment as subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and those who did not have both subjective cognitive complaints and objective cognitive impairments as cognitively normal (CN). We diagnosed major and minor depressive disorders according to the DSM-IV criteria. We defined dysphoria as the presence of depressed mood and anhedonia as lack of interest or pleasure for more than a half of day or more than seven days during the past two weeks.

Statistical analysis

To compare demographic characteristics between groups, we used Pearson’s chi-square test for categorical variables and independent samples t-test for continuous ones. We used multinomial logistic regression analysis to examine the influence of baseline dysphoria and anhedonia on future cognitive decline in the CN group. In this analysis, the dependent variable was categorized into four groups; 1) remained as CN, 2) progressed to SCD, 3) progressed to MCI, and 4) progressed to dementia. This model was adjusted for age, sex, education, CIRS score, CERAD-TS, and the presence of the apolipoprotein ε4 allele. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Dysphoria and anhedonia were more prevalent in women at the baseline assessment (p<0.001). The participants with anhedonia at the baseline assessment were less educated than those without anhedonia (p=0.028). However other baseline demographic and clinical characteristics did not differ based on the presence of dysphoria or anhedonia (Table 1).

Among the 2,685 CN participants who completed the 4-year follow-up assessment, 193 (7.2%) and 183 (6.8%) had dysphoria and anhedonia respectively at the baseline assessment. Among the 193 participants with dysphoria, 59 (30.6%) progressed to SCD, 39 (20.2%) to MCI, and eight (4.1%) to dementia during the 4-year follow-up period. Among the 183 participants with anhedonia, 51 (27.9%) progressed to SCD, 40 (21.9%) to MCI, and nine (4.9%) to dementia during the same follow-up period. In the multinomial logistic regression analysis, anhedonia was associated with an approximately two-fold higher risk of MCI (OR=2.089, 95% CI=1.198–3.641, p=0.008) and approximately five-fold higher risk of dementia (OR=5.073, 95% CI=1.436–17.922, p=0.012) but was not associated with the risk of SCD (OR=1.462, 95% CI=0.921–2.319, p=0.107). In contrast, dysphoria was associated with an approximately twofold higher risk of SCD (OR=2.058, 95% CI=1.329–3.186, p=0.001) and approximately 1.7-fold higher risk MCI (OR=1.748, 95% CI=1.004–3.045, p=0.048) but was not associated with the risk of dementia (OR=2.235, 95% CI=0.603–8.288, p=0.229) (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

In this study, dysphoria and anhedonia had differential impact on the future risk of cognitive decline in cognitively normal elderly individuals. Anhedonia was associated with the future risks of MCI and dementia but not with the risk of SCD while dysphoria was associated with the future risks of SCD and MCI but not with the risk of dementia.

Bäckman et al. [37] reported that motivation-related, but not mood-related, symptoms of depression were associated with cognitive performance in clinically non-depressed and nondemented elderly individuals. Recently, Donovan et al. [26] reported that subthreshold symptoms of depression were associated with AD biomarkers of neurodegeneration in older adults without overt cognitive impairment. In their study, higher apathy-anhedonia score, but not dysphoria score, was associated with lower cerebral glucose metabolism AD-related cortical regions. Marshall et al. [38] reported that greater apathy was associated with higher amyloid burden in MCI. In a prospective study with non-demented older adults, the patients with incident AD had more depressive symptoms than the participants without dementia at baseline, and motivation-related symptoms such as lack of interest, loss of energy, and concentration difficulties were dominant at the preclinical stage of AD [39].

Older adults who have dysphoria without anhedonia may be better adapting to depression. Loss of interest in usual activities may lead to less physical activity and greater social isolation, both of which increase the risk for dementia. Anhedonia may lead to a self-reinforcing cascade of events resulting in continually worsening cognition and functioning [40-42]. In addition, depression is commonly induced by cerebrovascular diseases in late life [43,44], and cerebrovascular diseases were more strongly associated with anhedonia than dysphoria [45]. To sum up, anhedonia, even when present at a subclinical level, may increase the future risk of dementia possibly via both amyloiddependent and amyloid-independent processes.

In contrast to anhedonia, dysphoria was associated with the future risk of SCD and MCI but not with the risk of dementia, indicating that dysphoria may increase the risk of subjective cognitive complaints but not with that of objective cognitive impairments. The determinants of subjective cognitive complaints are complex. In elderly individuals, subjective memory complaints can be either realistic self-observations on cognitive decline or secondary symptoms to depression [46]. Subjective cognitive complaints were found to be inconsistently related to current cognitive impairment but consistently related to depression and personality traits such as neuroticism [47]. In a large cross-sectional study on community-dwelling adults without dementia, subjective cognitive complaints were more likely related to symptoms of depression than concurrent cognitive impairment [48]. The subjects who most emphatically complained of memory disturbance had greater tendency toward somatic complaining, higher feelings of anxiety about their physical health, and more negative feelings of their own competence and capabilities than those who did not complain of memory deterioration associated with aging [49].

This study has several limitations. First, demographic and clinical characteristics of the responders to the follow-up evaluation were different from those of the non-responders. Second, apathy was not evaluated. Third, we evaluated the presence of dysphoria and anhedonia for only 2 weeks prior to the assessment despite that these symptoms are episodic in nature. Despite these limitations, however, anhedonia is more likely to increase future risk of dementia than dysphoria in cognitively normal elderly individuals.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Haesong Geriatric Psychiatry Research Fund from the Korean Mental Health Foundation.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptulization: Ki Woong Kim. Data curation: Ju Ri Lee, Ji Won Han. Formal Analysis & Software & Visualization & Writing—original draft: Ju Ri Lee, Ki Woong Kim. Funding acquisition: Ki Woong Kim. Investigation & Methodology & Resources & Writing—review & editing: Ju Ri Lee, Seung Wan Suh, Ji Won Han, Seonjeong Byun, Soon Jai Kwon, Kyoung Hwan Lee, Kyung Phil Kwak, Bong Jo Kim, Shin Gyeom Kim, Jeong Lan Kim, Tae Hui Kim, Seung-Ho Ryu, Seok Woo Moon, Joon Hyuk Park, Dong-Woo Lee, Jong Chul Youn, Dong Young Lee, Seok Bum Lee, Jung Jae Lee, Jin Hyeong Jhoo, Ki Woong Kim. Project administration & Supervision & Validation: Ki Woong Kim. Ji Won Han.