Adolescents’ Attitudes and Intentions toward Help-Seeking and Computer-Based Treatment for Depression

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Many depressed adolescents do not seek professional help despite there being evidence-based treatments for depression, such as cognitive behavioral therapy or computer-based therapy. To increase professional help-seeking behavior in depressed adolescents, it is necessary to positively change help-seeking attitudes. This study aimed to explore the effect of sub-groups of help-seeking attitudes, gender, and depression level on adolescents’ help-seeking intentions and their perceptions of computer-based psychotherapy.

Methods

Participants were 246 adolescents aged 13–18 years recruited from six middle and high schools in South Korea. Measures were self-administered questionnaires, and included the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale, the Intention to Seek Counseling Inventory, Preferences for Depression Treatment, and the Perceptions of Computerized Therapy Questionnaire.

Results

Help-seeking intentions were positively related with female gender and the recognition of the need for help. A higher level of confidence in therapists was related to high preference for computer-based therapy and face-to-face therapy. Adolescents with more severe depression were more likely to prefer pharmacotherapy. The perceptions of computer-based therapy were more positive in male adolescents, and in adolescents with a higher level of confidence in therapists yet a lower level of interpersonal openness.

Conclusion

To promote adolescents’ help-seeking behavior, improvement of the recognition of the need for help is required, especially among male adolescents. Computer-based therapy provides an alternative for male adolescents with high confidence in therapists yet low interpersonal openness. Consideration of the help-seeking attitudes and gender is needed when providing therapeutic intervention to depressed adolescents.

INTRODUCTION

Depression in adolescence is very prevalent and has negative impacts on the individual, their parents, peers, and society [1]. Well-established treatments have been available but often not accessible to adolescents. Depressed adolescents have shown a reduction in depressive symptoms, and improvements in psychosocial adaptation after receiving cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in many studies [2]. Recently, computer-based therapy has been shown to be effective in the treatment of adolescents with depression [3]. Early identification and treatment of depression could reduce the social cost and adaptation difficulties during adolescence and early adulthood [4]. However, the majority of depressed adolescents do not receive any treatment [5]. One study indicated that only one out of four adolescents with depression received professional help [6]. Adolescents may attempt to resolve their difficulties alone rather than seek professional help [7]. In particular, male adolescents do not tend to seek professional help, such as psychotherapy [8]. In South Korea, the mental health of adolescents is a serious issue, in that suicide is the leading cause of death in young people from their teenage years until their thirties [9]. However, the lifetime rate of mental health service use is very low at 22.2%, despite the presence of public mental health centers in every region, and psychotherapists available in middle or high schools in South Korea [9]. Therefore, it is necessary to encourage adolescents’ professional help-seeking behavior in the early stages of psychological issues such as depression.

Positive help-seeking attitudes can lead to help-seeking behaviors. Previous studies reported that through depression awareness education [10] or public campaigns [11], adolescents developed more positive attitudes towards help-seeking. According to planned behavior theory, the most powerful determinant of actual help-seeking behavior is help-seeking intentions [12]. Many studies have demonstrated that help-seeking attitudes predict help-seeking intentions [13,14]. However, there are few studies that specify which aspects of help-seeking attitudes predicted helpseeking intentions with adolescents.

Previous studies have consistently reported the effect of gender on help-seeking attitudes and intentions. Males have more negative help-seeking attitudes and lower intentions to seek help than females [8]. However, there are no specific studies regarding which aspects of help-seeking attitudes are influenced by gender. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate specific factors of help-seeking attitudes in order to promote professional help-seeking behavior in male adolescents.

It is particularly important in the case of depressed adolescents, to explore which specific factors of help-seeking attitudes lead to promoting help-seeking behaviors. One study investigated how depression level affects specific factors of help-seeking attitudes with undergraduate students [15]. However, to our knowledge, there is almost no study with adolescents. Furthermore, there has been inconsistency regarding the relationship between psychological distress, such as depression, and professional help-seeking intentions. Some studies have suggested that help-seeking attitudes, rather than psychological distress or depression, influenced help-seeking intentions [16,17]. In these studies which controlled for variables such as help-seeking attitudes, the effect of psychological distress on help-seeking intentions became nonsignificant. On the other hand, other studies have reported that help-seeking intentions decreased while psychological distress or depression worsened [18-20]. To develop an effective strategy to promote help-seeking behavior in adolescents with depression, the relationship between depression and help-seeking attitudes or intentions needs to be further investigated.

In addition, this study attempted to identify which aspects of help-seeking attitudes required focus to improve the accessibility of computer-based therapy. Aside from psychological factors such as help-seeking attitudes and intentions, there are structural barriers, such as time, region, and cost that may prevent adolescents from seeking professional psychological help [21]. Recently, computer-based therapies have emerged to overcome these barriers [22], and many studies have reported the effectiveness of computer-based treatment for depressed adolescents [23]. However, little is known about adolescents’ attitudes toward computer-based therapy. Adults have exhibited unfavorable intentions regarding the use of computer-based therapy in the future [24]. In studies investigating treatment preferences for depression, adults overwhelmingly preferred face-to-face therapy over computer-based therapy [25,26]. The main predictor of preference for computer-based therapy was the level of searching skills for health-related information [27]. Considering that adolescents search mental health related information on the internet more often than adults [28], we hypothesized that adolescents might have different preferences regarding computer-based therapy compared to adults. Previous studies on adolescents’ preference of depression treatment reported a comparison only between face-to-face therapy and pharmacotherapy-adolescents had a high preference for face-to face therapy over pharmacotherapy [29,30]. It has been shown that clients’ treatment preference was an important factor in treatment initiation and adherence [31] and was also associated with clinical outcomes [32]. However, there has been no research on adolescents’ preferences for depression treatment where computer-based therapy, face-to-face therapy, and pharmacotherapy are compared.

The aim of our study was to investigate variables that affect professional help-seeking behavior in depressed adolescents. In particular, we explored the effect of gender and depression on sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes, such as recognition of the need for help, stigma tolerance, interpersonal openness, and confidence in therapists. The current study also attempted to identify the effect of gender, depression, and sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes on help-seeking intentions. In addition, we explored the effect of help-seeking related variables on adolescents’ preference and perception toward computerbased therapy.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were 246 adolescents between the ages of 13 to 18 recruited from three middle schools and three high schools located in Seoul and surrounding suburbs (Table 1). After informed consent forms were distributed to adolescents and their parents by their teachers, and returned in enclosed envelopes, surveys were conducted in the classroom. The sample included 144 male and 102 female adolescents, of which 130 were middle school students and 116 were high school students.

Procedure

This study was conducted after permission was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB No. C-1805-163-948). English questionnaires were translated into Korean and then modified to improve understanding for adolescents. In order to verify the validity of translated questionnaires, we examined the content validity of the translated questionnaires with Content Validity Index (CVI) [33]. A CVI was calculated by ten researchers who had master’s degrees in clinical psychology and had completed at least one year of clinical practice. Ten researchers measured the relevance of each items by 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very inadequate) to 5 (very adequate). Questionnaires were also reviewed by two clinical psychologists who had more than ten years of clinical practice. Twenty adolescents participated in the pilot study, where items that were difficult to understand for adolescents were identified. After the pilot study, the final questionnaire was used for the current study.

We recruited participants in collaboration with teachers from local middle and high schools. After receiving informed consent from parents, researchers conducted the survey in classrooms with adolescents who voluntarily participated in the study. The majority of students from two classrooms from each school participated in the study. Researchers explained the study to students and conducted the survey after obtaining consent. The questionnaires took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Measures

Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help

Help-seeking attitudes were measured using the Korean version [34] of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help scale [35]. The scale consists of 29 items using a 4-point Likert-scale. The scale contains four sub-factors, including Recognition of the Need for Help, Stigma Tolerance, Interpersonal Openness, and Confidence in Therapists. Higher scores represent more positive attitudes toward professional helpseeking. Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale was 0.77 and that for the sub-factors ranged from 0.55 to 0.69.

Intentions to Seek Counseling Inventory

Professional help-seeking intentions were developed based on the Intentions to Seek Counseling Inventory (ISCI) [36]. Intentions to seek counseling services were measured when adolescents have specific problems such as depression, weight control, interpersonal problems. Considering the characteristics of Korean adolescents in statistical data provided by the Korea Youth Counseling and Welfare Institute [37], some items from the ISCI were modified. The item regarding difficulties with dating was excluded. Additionally, two items regarding relationship difficulties and difficulties with friends were merged into one item. Two items regarding self-understanding and loneliness were merged into one item to represent personality problems. Items for anger control problem and juvenile delinquency were added. The revised version contained 18 items using a 4-point Likert scale, while the original ISCI contained 17 items using a 6-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alpha for this modified version of the ISCI was 0.92.

Perceived positive past experience

Past experiences of help-seeking behavior and the perceived extent of helpfulness were measured using two translated questions from the original version of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire [38]. The first question was rephrased as “Have you ever gone to a mental health professional (counselor, therapist, and psychiatrist) to receive help for a personal problem?” Participants could respond with “yes” (1) or “no” (2). When participants reported “yes,” the second question was given as “How helpful were the experiences with these professionals?.” Participants could then respond on a 5-point Likert scale from “very unhelpful” (1) to “very helpful” (5).

Barriers to Adolescents Seeking Help

Barriers to professional help-seeking were measured with the Korean version of the 37-item Barriers to Adolescents Seeking Help (BASH) scale [39]. The scale included barriers such as confidentiality, stigma, and self-sufficiency on a 4-point Likerttype form. Higher scores indicated there were many barriers to seeking help. The total Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The depression severity of adolescents was measured using the Korean version [40] of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9) [41]. This scale contains nine questions on with 4-point Likert scale from ”not at all” (0) to ”nearly every day” (3). Total scores between 5 and 9 indicated mild depression, whilst scores from 10 to 14 signified moderate depression. The overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89.

Preferences for depression treatment

Preference for depression treatment was assessed after participants read descriptions of three therapies including pharmacotherapy, face-to-face therapy, and computer-based therapy. Based on a previous study of adolescents’ preferences for depression treatment [42], the descriptions were written in a format that would be easy for adolescents to understand, and included less than 70 words for each option about pharmacotherapy, individualized CBT, or a computer-based CBT program. The questionnaire was developed in Korean for this study, and used three items with a 5-point Likert-type scale form after reviewing measures used in previous studies, such as ranking preferences [43] and questions regarding preferences for treatment [44]. In previous study, the preference was assessed with 5 items for each treatment [44]. However, the original item content was not appropriate, considering the lack of psychotherapy experience of Korean adolescents. And in case the preference was measured in ranking method, ranking order cannot be statistically calculated because of its characteristics as nominal data. When assessing the preference of three treatment options in 5-point Likert scale, the ranking of the preference among the three treatments can be identified according to the score assigned to each treatment. Therefore, in this study the preferences of three treatment options were measured by three items in Likert scale. Each preference for the three options was assessed by the degree of preference from “not very preferred” (1) to “very preferred” (5).

Perceptions of Computerized Therapy Questionnaire

The Perceptions of Computerized Therapy Questionnaire (PCTQ) [45] was translated into Korean for adolescents with a 7-point Likert scale without any content modification. It included 30 items containing of five factors: relative advantage (i.e., that computer-based therapy had any advantage compared to traditional psychotherapy), compatibility (i.e., that the computer-based therapy would fit well with the way one would like to receive therapy), complexity (i.e., in using computer-based therapy), observability (i.e., observing that acquaintances have used computer-based therapy), and trialability (i.e., that one can try out computer-based therapy before using it). In this study CVI was calculated in two times. First CVI was 0.74 and second one was 0.84 while 0.80 of CVI is considered acceptable [33]. The overall Cronbach’s alpha was 0.93.

Statistical analyses

SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. A multiple regression was conducted to investigate the effects of the independent variables on help-seeking attitudes and intentions, the treatment preference for depression, and the perceptions of computerized therapy. A repeated-measures ANOVA was used to examine the difference in the preferences in treatment options for pharmacotherapy, face-to-face therapy, or computer-based therapy. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed) in all tests.

RESULTS

The effects of gender and depression on help-seeking attitudes

The main effects of gender and depression on help-seeking attitudes were significant (F=12.800, p<0.001) (Table 2). Less severe depression was related to a higher score on the scale of help-seeking attitudes (β=-0.321, p<0.001). Female adolescents scored more highly on help-seeking attitudes compared to male adolescents (β=0.142, p<0.05).

An additional analysis was conducted to examine the effect of gender and depression on the sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes. First, with recognition of the need for help as the dependent variable, only the main effect of gender was a significant independent variable (F=12.021, p<0.001). Female adolescents reported greater recognition than male adolescents (β= 0.255, p<0.001). Second, the main effects of gender and depression on stigma tolerance were significant (F=9.277, p<0.001). Less severe depression was related with higher stigma tolerance (β=-0.253, p<0.001). Female adolescents reported higher stigma tolerance than male adolescents (β=0.190, p<0.01). Third, the main effect of depression on interpersonal openness was significant (F=41.525, p<0.001). Less severe depression was related with higher interpersonal openness (β=-0.494, p<0.001). Last, the main effect of depression on confidence in therapists was significant (F=4.877, p<0.01). Less severe depression was related with higher confidence in therapists (β=-0.199, p<0.01).

The effects of gender, depression, and help-seeking attitudes on help-seeking intentions

The main effects of gender and depression on help-seeking intentions were significant (F=9.528, p<0.001) (Table 3). Female adolescents demonstrated more help-seeking intentions than male adolescents (β=0.224, p<0.01). More severe depression was related to higher help-seeking intentions (β=0.163, p<0.05). Positive help-seeking attitudes trended towards higher help-seeking intentions (β=0.125, p=0.051).

Multiple regression for the effects of gender, depression, and help-seeking attitudes on help-seeking intentions (N=246)

Additional analysis was conducted to investigate the relationship between sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes and help-seeking intentions. As a result of multiple regression with gender, depression, and sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes as independent variables, there were significant main effects of gender and recognition of the need for help (F=6.046, p<0.001). Female adolescents had higher help-seeking intentions than male adolescents (β=0.178, p<0.01). A higher level of recognition of the need for help was related to higher help-seeking intentions (β=0.194, p<0.01). However, after adding the sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes as an independent variable, the main effect of depression was not significant (β=0.072, p>0.05).

Comparison of preferences for depression treatment

There was a significant difference among the preferences for the three treatment options: pharmacotherapy, face-to-face therapy, or computer-based therapy (F=122.135, p<0.001). Using the Bonferroni post-hoc test, there were significant differences between each two treatment options (p<0.001). The preference for face-to-face therapy was the highest (M=3.77, SD=0.98), whilst preference for computer-based therapy was second (M=3.02, SD=1.05), and pharmacotherapy was third (M=2.39, SD=1.12).

The effects of gender, depression, and help-seeking attitudes on the preferences for each treatment option

High confidence in therapists was related with preference for computer-based therapy and face-to-face therapy. Severe depression was related to a preference for pharmacotherapy.

First, the main effect of depression on the preference for pharmacotherapy was significant. More severe depression was related to a preference for pharmacotherapy (β=0.271, p<0.001). Three independent variables accounted for 8.2% of the variance (F=8.252, p<0.001).

Second, the main effect of help-seeking attitudes on the preference of face-to-face therapy was significant. Positive helpseeking attitudes were related to a preference for face-to-face therapy (β=0.306, p<0.001). Three independent variables accounted for 8.5% of the variance (F=8.449, p<0.001).

An additional analysis was conducted to investigate the effects of sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes on the preference of face-to-face therapy. Higher level of confidence in therapists was related to a preference for face-to-face therapy (β=0.194, p<0.01). Six independent variables accounted for 7.8% of the variance (F=4.392, p<0.001).

Third, high confidence in therapists was related to a preference for computer-based therapy (β=0.168, p<0.05).

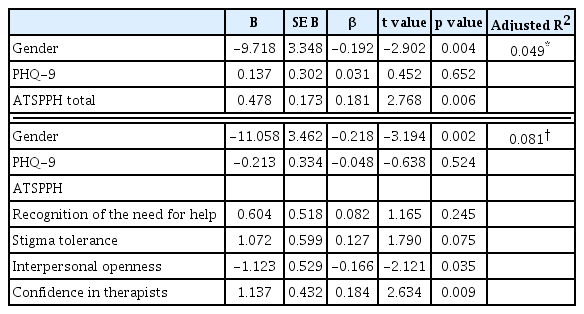

The effects of gender, depression, and help-seeking attitudes on the perceptions of computer-based therapy

Perceptions for computer-based therapy were more positive in male adolescents and adolescents with high confidence in therapists yet low interpersonal openness (Table 4).

Multiple regression for the effects of gender, depression, and help-seeking attitudes on the perceptions of computer-based therapy (N=246)

The main effects of gender and help-seeking attitudes were significant (F=5.217, p<0.01). Male adolescents had more positive perceptions of computer-based therapy than female adolescents (β=-0.192, p<0.01). The level of help-seeking attitudes was positively related with perceptions of computer-based therapy (β=0.181, p<0.01).

An additional analysis was conducted to investigate the effects of gender, depression, and the sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes. The main effects of gender, interpersonal openness, confidence in therapist were significant (F=4.623, p<0.001). Male adolescents had more positive perceptions of computer-based therapy than female adolescents (β=-0.218, p<0.01). High level of confidence in therapists was related to positive perceptions of computer-based therapy (β=0.184, p<0.01). Low level of interpersonal openness was related to more favorable perceptions of computer-based therapy (β=-0.166, p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study found that help-seeking intentions were positively associated with female gender and the recognition of the need for help, one of the sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes. High confidence in therapists was positively related to the preference and the perception of computer-based therapy. In addition, male adolescents and adolescents with low interpersonal openness perceived computer-based therapy more favorably.

Female adolescents or adolescents with higher recognition of the need for help exhibited more favorable help-seeking intentions. In a previous study among undergraduate students, help-seeking intentions were positively associated with the recognition of the need for help and interpersonal openness of help-seeking attitudes [20]. In this study, adolescents’ help-seeking intentions were positively associated only with recognition of the need for help among sub-factors of help-seeking attitudes. In accordance with previous studies, female adolescents reported more favorable help-seeking intentions than male adolescents [13,18,46,47].

In this study, help-seeking intentions were influenced by gender and the recognition of the need for help rather than depression level. However, more severe depression was related to higher help-seeking intentions when we analyzed the results after excluding the help-seeking attitude sub-factors. This result is consistent with that of a previous study [47], suggesting that severe depression was associated with actual help-seeking behavior such as choosing medications or professional psychotherapy. Our results indicated that although depressed adolescents exhibited high help-seeking intentions, adolescents’ helpseeking intentions would vary depending on their help-seeking attitudes, especially regarding recognition of the need for help. This result corresponds with planned behavior theory, in which help-seeking attitudes are posited to have an impact on helpseeking intentions. This is in agreement with the findings of previous studies, indicating that the effect of psychological distress on help-seeking intentions is not significant after considering variables related to help-seeking attitudes [16,17]. On the other hand, other studies have suggested that more severe depression is related to lower help-seeking intentions. However, in these studies, participants were asked only one question about helpseeking intentions after being presented with a vignette of a depressed adolescent [18] or after supposing that participants were experiencing depressive symptoms [13]. This could raise the issue of psychometric validity when measuring professional helpseeking intentions with only one item [48]. In a study conducted by Dardas et al. [46], more severe depression was positively associated with higher scores on the two items from the help-seeking intentions scale, which included conflicting intentions; the first item was “I would be willing to seek a therapy” and the second item was “I would not seek treatment from a professional.” This result indicates that depressed adolescents demonstrate inconsistent responding depending on how researchers measure help-seeking intentions. Therefore, future studies will be required to investigate which method can best predict actual help-seeking behavior.

With respect to the treatment preference for depression, we found that adolescents ranked their preferences in the following order: face-to-face therapy, computer-based therapy, and pharmacotherapy. As with previous studies with adults [25], adolescents preferred face-to-face therapy to computer-based therapy. However, adolescents preferred computer-based therapy to pharmacotherapy, suggesting that adolescents hold a relatively positive attitude toward computer-based therapy. Computer-based therapy may be an attractive alternative therapy to adolescents who were reluctant to pharmacotherapy. In addition, more severe depression was associated with a preference for pharmacotherapy. Adolescents’ preference is consistent with the clinical guideline for depressed adolescents, that pharmacotherapy should be considered for severe depression [49]. Evidence-based treatment, such as combined pharmacotherapy and CBT is recommended for adolescents with moderate to severe depression.

Our results regarding adolescents’ attitudes toward computer-based therapy showed that a higher level of confidence in therapists was associated with a favorable perception and preference for computer-based therapy. Male gender and a lower level of interpersonal openness were related to a positive perception of computer-based therapy. Regarding confidence in therapists, it is interesting that this was a significant variable of the perception of computer-based therapy. In a previous study [50] undergraduate students with a higher level of stigma held a positive attitude toward online psychotherapy. However, in the case of adolescents, factors influencing the attitudes toward computer-based therapy were confidence in therapists, interpersonal openness, gender rather than the stigma among helpseeking attitudes.

This study demonstrates important clinical implications in the treatment adolescents’ depression. In accordance with a previous study [16], strategies focusing on psycho-social factors such as help-seeking attitudes could be effective in promoting helpseeking behavior in regards to depression treatment. Especially for male adolescents, it is necessary to focus on recognition of the need of help. We propose that professionals need to consider adolescents’ contradictory attitudes toward psychotherapy when educating universal depression awareness programs or recommending therapy to adolescents. Adolescents may hesitate to seek professional help, although they recognize the necessity of external help in cases of severe psychological distress or depression. There should be a process of demonstrating the recognition of psychotherapy to depressed adolescents while exploring their barriers to professional help-seeking. It is essential to educate adolescents that psychological distress cannot be solved by one’s own efforts and can be overcome with professional help before symptoms worsen. We also expect that computer-based therapy can be an alternative therapy to depressed adolescents who are isolated from professional help, especially male adolescents who have difficulties being open with other people. And the confidence in therapists needs to be considered when recommending computer-based therapy. For adolescents, it could be important whether therapists who recommend computer-based therapy are reliable, or whether a computer-based therapy program was developed by trustworthy professionals.

This study has several limitations. There were limitations on the generalizability of our results, in that the region of participants was restrictive to Seoul, the capital of South Korea, and its surrounding suburbs. Among measures used in our study, a validation study is needed for the Korean version of the questionnaires, especially for PCTQ. The cross-sectional results in our studies should not be interpreted as a causal relationship, because adolescents may report dishonestly about their attitudes or behaviors in self-reported questionnaires. It is essential to measure actual professional help-seeking behavior through longitudinal studies to investigate the predictors of actual helpseeking behaviors. Although in this study we measured helpseeking intentions and previous help-seeking experience, it is important to assess actual help-seeking experiences after a certain period in order to confirm which help-seeking attitudes can predict actual help-seeking behaviors.

In conclusion, this study suggested the need to focus on enhancing professional help-seeking attitudes to promote helpseeking or to recommend a therapy for depressed adolescents. It demonstrated the importance of recognition of professional help in order to promote adolescents’ help-seeking, especially for male adolescents. When recommending computer-based therapy to adolescents, professionals need to consider adolescents’ confidence in therapists. This study also indicated that computer-based therapy can be an alternative therapy to male adolescents, or adolescents with low interpersonal openness. In order to prevent mental health issues among adolescents, consideration of help-seeking attitudes is required for improving accessibility of depression treatment including computerbased therapy, whilst carefully considering the influence of gender.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant of Ministry of Science and ICT, Republic of Korea (Grant No. 2017R1A2B4011725).

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Min-Sup Shin, Ryemi Do. Data curation & Formal analysis: All authors. Funding acquisition: Min-Sup Shin. Investigation & Methodology & Resources & Software & Project administration: All authors. Supervision & Validation: Min-Sup Shin. Visualization & Writing— original draft & review & editing: All authors.