Annual Prevalence and Incidence of Schizophrenia and Similar Psychotic Disorders in the Republic of Korea: A National Health Insurance Data-Based Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

We conducted this study to address the incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia and similar psychosis in South Korea with Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) database.

Methods

We used HIRA database, which includes diagnostic information of nearly all Korean nationals to collect number of cases with diagnosis of schizophrenia and schizophrenia-similar disorders (SSP), including schizophreniform, acute/transient psychotic disorders, schizoaffective disorders, and other/unspecific nonorganic psychosis (ICD-10 codes F20/23/25/28/29) between 2010 and 2015. The annual prevalence and incidence were calculated using the population data from the Korean Statistical Office.

Results

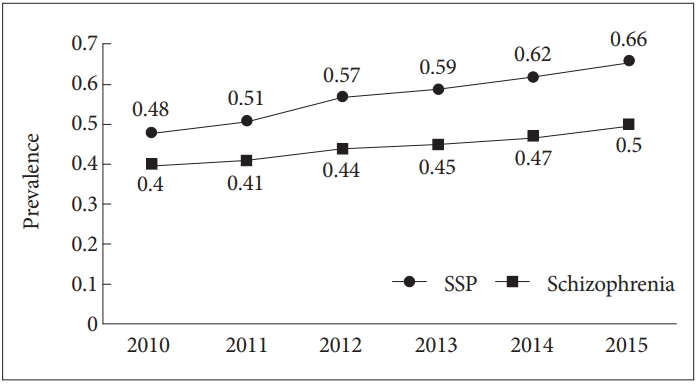

The 12-month prevalence of SSP of Korea between 2010 and 2015 were 0.48–0.66%. The 12-month prevalence of schizophrenia were 0.40–0.52%; The annual incidence rates (IR) of SSP between 2010 and 2015 were 118.8–148.7 per 100,000 person-year (PY). For schizophrenia, IR per 100,000 PY were 77.6–88.5 between 2010 and 2015.

Conclusion

The 12-month prevalence found in the present study was higher than that reported in community-based epidemiologic studies in South Korea but similar to those from other countries. The annual incidence of SSP and schizophrenia was found to steadily increase and was higher than that of other countries. The high incidence rate observed in the current study needs to be studied further.

INTRODUCTION

Psychosis, including schizophrenia and similar psychotic disorders, is representative of severe mental illness and is not uncommon. It places a huge economic burden on both patients and their families. According to a study from 2005, the overall cost of schizophrenia was estimated to exceed 3,000 million USD in the South Korea [1]. Specifically, unemployment was identified as the largest component of the overall cost, while the direct healthcare cost was estimated to exceed 400 million USD.

To properly handle the issue of severe mental illness, it is necessary to accurately understand the situation. Many studies investigating the epidemiology of schizophrenia have been conducted worldwide and have reported a lifetime prevalence of 0.3–0.7% [2-4], with an estimated 23.6 million people being affected globally [5]. In Korea, a series of nation-representing psychiatric epidemiologic studies (Korean Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study) were also performed at 5-year intervals. In a third survey in 2011, the lifetime prevalence of psychotic disorders and schizophrenia were 0.6% and 0.1%, whereas the 12-month prevalence were 0.4% and 0.1%, respectively [6]. The follow up study in 2016 reported a 0.5% lifetime prevalence and 0.2% 12-month prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (including schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder and brief psychotic disorder) [7]. These community studies have limitation that while they are well designed, their sample size of 5,102–6,022 were not sufficient for accurate estimation of rarer disorders like schizophrenia.

Therefore, we analyzed the South Korean database of Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA), which contain the health utilization data of all Korean nationals to estimate the incidence and prevalence of schizophrenia. Two previous studies have reported the prevalence of schizophrenia using this Korean national database; however, they comprised either 1 year of the database1 or 2 years, with a focus on first onset psychosis [8].

METHODS

Data source and study population

We collected diagnostic data from the whole HIRA database of year 2010 to 2015. We defined schizophrenia and similar psychotic disorders as diagnostic codes of schizophrenia, schizophreniform, acute/transient psychotic disorders, schizoaffective disorders, and other/unspecific nonorganic psychosis (ICD-10 F20, F23, F25, F28, and F29). The data of the patients who visited any medical facility with those codes between 2010 and 2015 were collected. To exclude possible diagnostic leniency, we only counted cases having those code as primary diagnosis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review boards of the Seoul National University Hospital with an IRB No of 1705-106-855.

Statistical analysis

With regard to 12-month prevalence, we analyzed patients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or similar disorders in a given year, between 2010 and 2015. For a denominator, we used the population figure from resident registry data [9]. To identify incident cases from the pool of prevalent cases, we excluded cases that had a prior diagnosis of psychotic disorders during the observation period. To give at least 1 year of clearance period in obtaining the incident cases, we calculated the annual incidence from year 2011. Annual incidence rate (IR) was calculated as the number of new cases divided by the estimated annual population of each year. However, it is presented as “per-year (PY)” regardless of not applying time in the denominator, since this type of calculation turns out to be comparable to a person-time rate [10]. All the statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software SAS Enterprise Guide, version 6.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Number of patients with schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea, between 2010 and 2015

In total, 598,951 patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders (SSP) during these 5 years, and, of these, 288,233 were males (48.1%) and 310,718 were females (51.9%) (Figure 1). Schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis with 444,480 patients (ICD-10 code F20.0-F20.9), with 217,366 males (48.5%) and 231,114 females (51.5%). The second most common diagnosis was unspecified nonorganic psychotic disorders (ICD-10 F29), followed by acute/transitional psychotic disorders (ICD-10 F23), schizoaffective disorders (ICD-10 F25) and other nonorganic psychotic disorders (ICD-10 F28). The portion of female patients was higher for every diagnosis.

Total number of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea between 2010 and 2015. SSP: Schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders, including Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform disorder, Acute and Transient Psychotic disorder, schizoaffective disorders, and other/unspecific non-organic psychotic disorders.

A 12-month prevalence of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea between 2010 and 2015

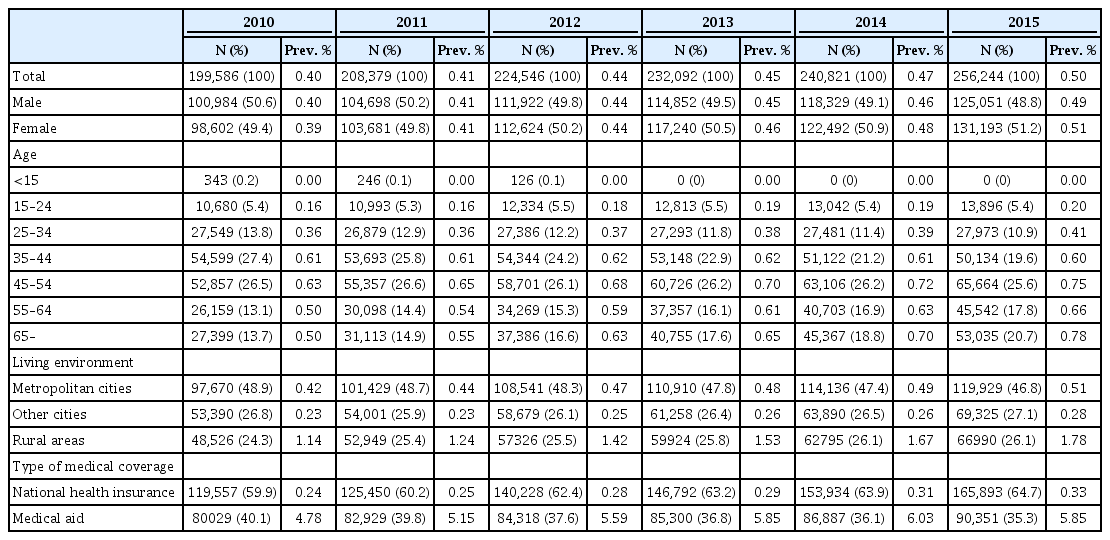

As shown in Table 1, 242,490 patients were diagnosed with SSP in 2010, with 12-month prevalence 0.48%. The numbers have increased annually, up to 340,546 diagnosed patients in 2015, translated into a 12-month prevalence of 0.66%. The 12-month prevalence was highest in the age groups of 35–44 and 45–54 (0.71% and 0.72%) in 2010, and the younger adults, below age of 44 reported a lower prevalence of psychosis than the middle to the older adults (above 45 years of age) throughout the 5 years. This trend became more prominent over the observational period and the age group with the highest prevalence of psychosis in 2015 was the over-65 years of age group, with a prevalence rate of 1.18%.

The 12-month prevalence of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea between 2010 and 2015

To understand how the socio-economic factors affect prevalence, we examined the data according to both the living environment and the type of medical coverage. The 12-month prevalence of rural areas was approximately 5- or 6-fold higher than that of non-metropolitan city areas. Additionally, during the 5 years, the prevalence increased by 72.8% in rural areas, in contrast to the 37.5% observed in the whole population. With regard to medical coverage, the 12-month prevalence was between 5.38% and 6.92% for medical aid (MA) recipients (e.g., the beneficiaries of basic social protection from the government), in contrast to the 0.31–0.46% for national health insurance (NHI) recipients.

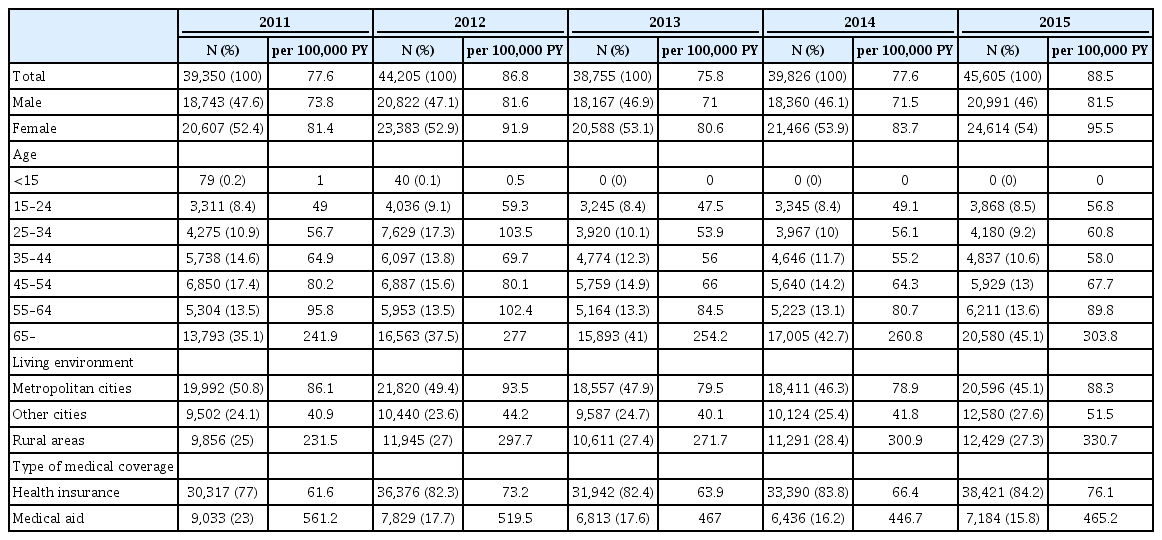

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, although 199,586 patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia in 2010, with a 12-month prevalence of 0.40%, this number increased annually, reaching a prevalence of 0.52% in 2015. The female population reported a more rapid rise in prevalence of schizophrenia than the male population.

The 12-month prevalence of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea between 2010 and 2015. SSP: Schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders, including Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform disorder, Acute and Transient Psychotic disorder, schizoaffective disorders, and other/unspecific nonorganic psychotic disorders.

The characteristics of prevalence of schizophrenia were similar to those of SSP. In fact, the prevalence of schizophrenia was higher between the 35–44 and 45–54 (0.61% and 0.63%) age groups, being relatively higher in the older age group when compared to the younger group. In 2015, the prevalence of psychosis was the highest in the over 65 age group (0.78%). Prevalence was also greater in rural areas when compared to both metropolitan and non-metropolitan city areas. Similarly, the medical aid beneficiaries showed a much higher prevalence of schizophrenia.

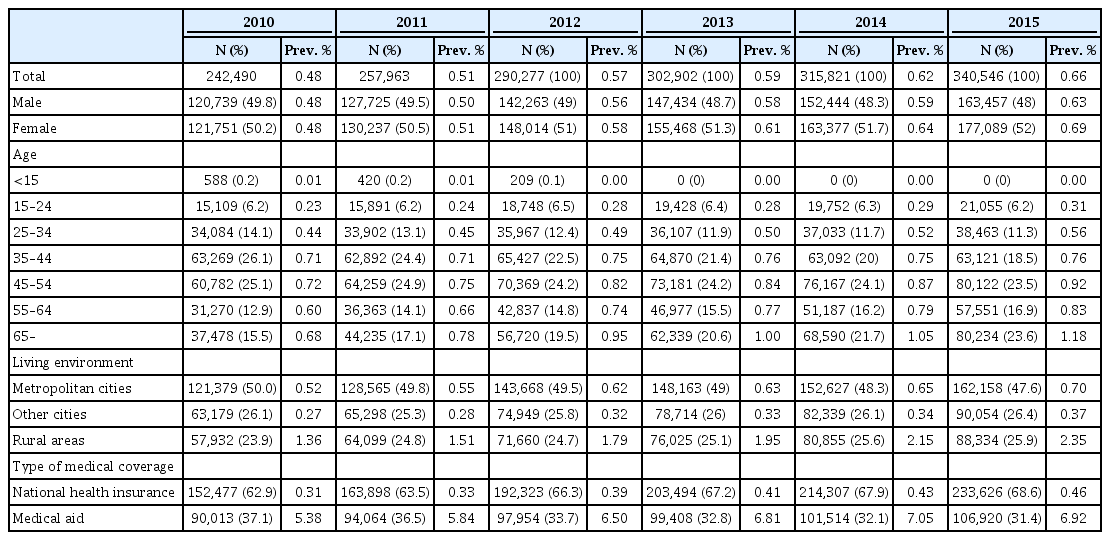

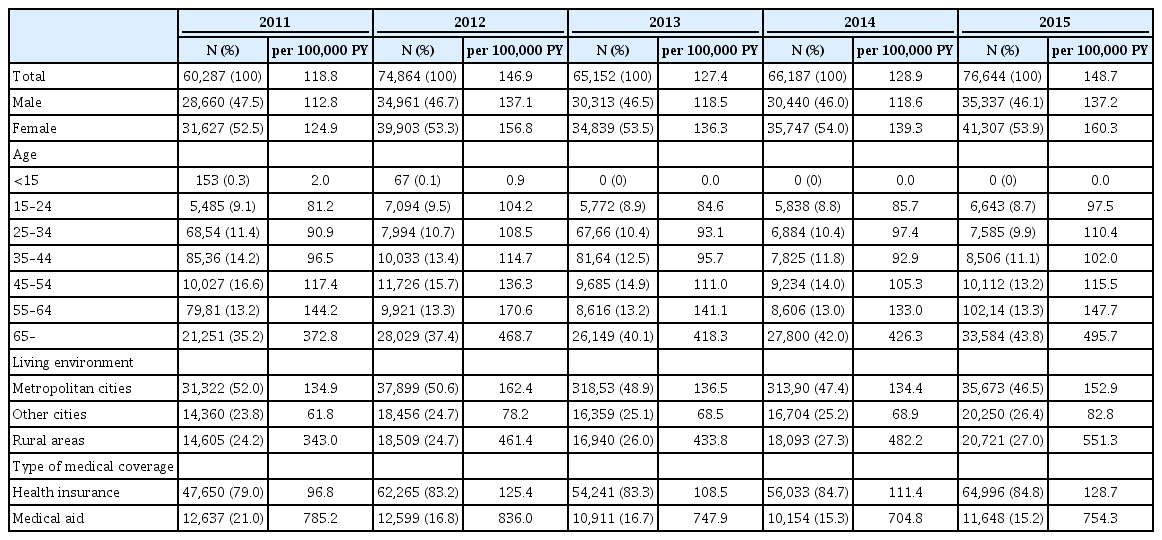

Annual incidence of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea between 2011 and 2015

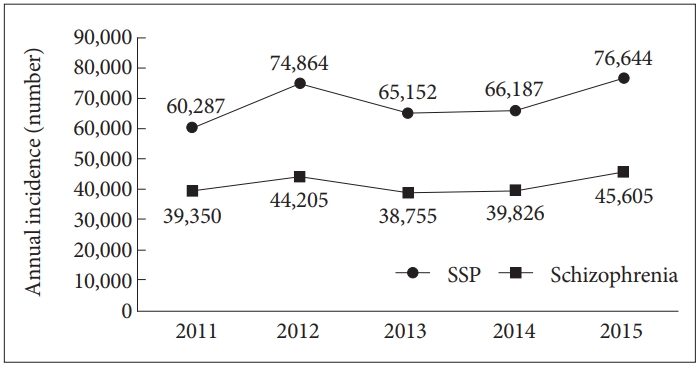

In total, 343,134 patients were newly diagnosed with SSP between 2011 and 2015 (Table 3, Figure 3); of them, 53.5% were female and 46.5% were male. The annual incidence (IR) of SSP was 118.8 per 100,000 person-year (PY) in 2010 and in 2015, and it was increased to 148.7/100,000 PY. Across the 5 years of observation, IR was higher in females, with a female to male ratio of 1.10 (in 2011) and 1.16 (in 2015). Additionally, the IR of SSP was greater in the older age group. Although the IR was 81.2/100,000 PY in the 15–24 year age group in 2010, it rose to 144.2 in the 55–64 age group, and 372.8 in the 65+ age group. In 2015, the IR of SSP was 97.5/100,000 PY in the 15–24 age group and 495.7/100,000 PY in the 65+ age group. The IR of schizophrenia in the republic of Korea was 77.6/100,000 PY in 2011, while it rose to 88.5/100,000 PY in 2015. Furthermore, the 65+ age group showed the highest IR (231.5–303.8/100,000 PY) (Table 4, Figure 3).

Annual incidence of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea between 2011 and 2015

Annual incidence of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in the Republic of Korea between 2011 and 2015. SSP: Schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders, including Schizophrenia, Schizophreniform disorder, Acute and Transient Psychotic disorder, schizoaffective disorders, and other/unspecific non-organic psychotic disorder.

The patterns related to both the living environments and the medical coverage were similar to those associated with prevalence both in schizophrenia and SSP. Rural areas reported a higher IR than both metropolitan and non-metropolitan city areas. Furthermore, the MA beneficiaries presented a 5.8 to 8.1-fold increase in their IR as opposed to the people with the national health insurance.

DISCUSSION

Throughout the 5 years of observation, 598,951 patients were diagnosed with schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders in South Korea. Our investigation is the first to take into consideration multiple years of the HIRA database containing data of almost all Korean nationals to calculate both the prevalence and the incidence of SSP in South Korea. However, it should be noted that the prevalence and incidence mentioned here are from “treated” cases, meaning that the “true” prevalence or incidence must be higher as there would be some cases not under treatment. However, both the 12-month prevalence and the IR are much beyond the expectations of the common clinical wisdom and of the estimates from community studies. Therefore, we suppose the “true” incidence and prevalence rates not to be much different from the numbers reported in this study.

The prevalence of schizophrenia or similar psychotic disorders found in our study was in line with a previous study using the HIRA database from year 2005 [1], or similar studies from other nations [4,3,11]. However, this rate is much higher than that reported in the national-representing KECA series, which reported only 0.1–0.2% 12 month prevalence of schizophrenia [6,7,12,13]. The low prevalence seen in the KECA series might be due to the characteristics of the community samples. Psychosis-like symptoms tend to be underreported, in part due to the stigma associated with the disorder and in part due to the high specificity but low sensitivity of community-surveying instruments of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) [14]. Moreover, considering that schizophrenia is a relatively rare disorder, the sample size was too small to estimate accurate prevalence in CIDI studies. Indeed, with a few exceptions [15], substantial CIDI studies including samples from US, Europe and worldwide [16-18] did not report the prevalence of psychosis in peer-reviewed journals. In another study, Cho et al. [19] investigated the prevalence rates of schizophrenia in the combined populations hospitals, psychiatric nursing facilities and homeless asylums and reported the lifetime and one year prevalences of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders as 1.19% to 1.32% and 0.51% to 0.61%, respectively.

With regard to the incidence of psychotic disorders, a recent study conducted in 2017 showed the number of newly diagnosed psychotic patients in the Republic of Korea in 2006 and 2007 [8], which can be translated into 29.8 per 100,000 PY, a much lower rate than the numbers found in our study. Since the above-mentioned study used the same HIRA dataset, at different time periods, we can assume that the incidence of treated schizophrenia or similar disorders, if not the true incidence, is increasing in Korea.

Several explanations related to the observed increase in incidence are possible. First, the constant increase of psychiatric beds, and somewhat lessened stigma to the psychiatric treatment in Korea in recent years might explain the increase [20], since this estimate is of treated cases and not true incidence in itself. If this is the case, this result showing higher treatment incidence rate in older age groups than in younger age groups might indicate severe treatment delays for schizophrenia in Korea.

However, this increase might represent real changes in the true incidence rate of psychosis. Some studies from other countries suggested use of illegal drugs and possible cohort effects as reason of increased incidence [20,21]. In this study, the higher incidence found in the older age group might indicate cohort effects. The generation was born before 1950 and has spent their young age either during World War II or the Korean War, experiencing rapid transitions towards an industrialized economy during their working years, and unprecedented rapid societal changes during their whole adulthood. Therefore, these socio-economic factors may have left them more vulnerable to major psychotic disorders, although this hypothesis needs to be explored further to fully determine what the risk had been.

It is also of note that, although several studies from the 1990s and early 2000s described a decreasing incidence of schizophrenia [3,22-24], more recent studies tend to be reporting increasing incidences [20,21,25]. Nevertheless, the incidence rate of schizophrenia in this study is very high compared to that reported for other countries. There were similar studies based on national/universal health insurance data from Taiwan and Quebec, and these studies reported incidence of schizophrenia as 45–94/100,000 PY [3,26]. Study using GP database of Netherland indicated incidence of 22/100,000 PY over 10 year-period, and a study using the Danish Psychiatric Central Registry reported the incidence of schizophrenia to be 31–40/100,000 PY [25,27]. For a meta-analysis result, a study from England showed a pooled incidence of 31.7/100,000 PY for all psychosis and of 15.2 for schizophrenia [28], and another meta-analysis reported a 23.7/100,000 PY [11].

This high incidence in Korea may be in part due to the methodological limitations of this study. Because the dataset used is from 2010, the cases identified as new cases in 2011 or 2012 only had either 1 or 2 years of clearance ahead of them; therefore, they may include relapse cases. Indeed, the study from Quebec showed that compared to the 10-year clearance period, more than 6 years of clearance is required to achieve an excellent Kappa coefficient value [26]. However, the incidence rate of year 2015 would be reasonable estimate, since data from 2015 contains 5 years of clearance ahead of them, and especially estimate for the younger age groups (15–24 years old) are likely to be accurate. There might be also diagnostic validity issues resulting from the diagnostic leniency required to use medications off-label in South Korea, especially in the older age group, since dataset was from claims data of health insurance. However, we only included cases with primary diagnosis of schizophrenia, it would be less likely. Nevertheless, diagnostic validity for this study would be improved if additional information like prescribed medications, specialty of physicians who made relevant diagnosis and frequency of outpatient visits was available.

Regardless of these limitations, the present study is one of the first to report a reliable incidence rate of schizophrenia in South Korea and to draw attention to the urge of service requirements to address mental health in public. We found the incidence of schizophrenia or similar disorders to be very high, with the possibility of prevailed delayed treatment until the older age. Exploring the possible cohort effects that render the older people more vulnerable and adapting a more rigorous early detection (for younger adults) and treatment programs for psychosis are of extreme importance nation-wide.

Acknowledgements

The idea of study was inspired during the analysis for development of mental health policy of Seoul. We hereby thanks to all staffs of Seoul Mental Health Center and Health Policy Division of Seoul Metropolitan Government for their enthusiasm and contribution for the betterment of mental health in Seoul.

There was no research grant directly associated to this study.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Jin Yong Lee, Jee Hoon Sohn. Data curation: Jungmee Kim. Formal analysis: Jungmee Kim. Investigation: Sung Joon Cho, Yeon Ju Kang, Seung Yeon Lee. Methodology: Jungmee Kim, Jin Yong Lee. Project administration: Jee Hoon Sohn. Supervision: Jin Yong Lee, Jee Hoon Sohn. Validation: Sung Joon cho, Hwo Yeon Seo, Kyoung-Nam Kim, Jee Eun Park. Writing—original draft: Sung Joon Cho, Jungmee Kim, Jee Hoon Sohn, Jin Yong Lee. Writing—review & editing: Hwo Yeon Seo, Yeon Ju Kang, Seung Yeon Lee, Haebin Kim, Kyoung-Nam Kim, Jee Eun Park.