“Suicide CARE” (Standardized Suicide Prevention Program for Gatekeeper Intervention in Korea): An Update

Article information

Abstract

Objective

In 2011, “Suicide CARE” (Standardized Suicide Prevention Program for Gatekeeper Intervention in Korea) was originally developed for the early detection of warning signs of suicide completion, since there is a tendency to regard emotional suppression as a virtue of Korean traditional culture. A total of 1.2 million individuals completed the training program of “Suicide CARE” in Korea.

Methods

More sophisticated suicide prevention approaches according to age, sex, and occupation have been proposed, demanding for a more detailed revision of “Suicide CARE.” Thus, during the period from August 2019 to February 2020, “Suicide CARE” has been updated to version 2.0. The assessments on domestic gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention, international gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention, psychological autopsy interview reports between 2015 and 2018, and the evaluation of feedback from people who completed “Suicide CARE” version 1.6 training were performed.

Results

We describe the revision process of “Suicide CARE,” revealing that “Suicide CARE” version 2.0 has been developed using an evidence-based methodology.

Conclusion

It is expected that “Suicide CARE” version 2.0 be positioned as the basic framework for many developing gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention in Korea in the near future.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is the most important public mental health issue in Korea [1-4]. From 2003 to 2016, Korea has reported the highest suicide rate among the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. Since Lithuania joined the OECD in 2017, the highest suicide rate among the OECD countries, in just a year, was reported by Lithuania. Thus, Korea reported the second-highest suicide rate among the OECD countries. However, the statistics for suicide have remained troubling, as follows: As of 2018, the death rate due to suicide per 100,000 persons was 26.6 in Korea, which was much higher than the average suicide death rate of 11.6 in the other OECD countries [5]. Recently, the “National Suicide Prevention Action Plan” of Ministry of Health and Welfare of Korea has aimed to reduce suicide death rate to less than 20 per 100,000 persons by 2022 and total completed suicides to less than 10,000 persons per year [6]. A recent systematic review reported that restricting access to lethal means and conducting school-based awareness programs were sufficiently evidenced to prevent suicide. In addition, effective pharmacological and psychological treatments for depression, gatekeeper training, education of physicians, and internet and helpline support have been proposed as evidence-based suicide prevention strategies. However, screening in primary care and general public education and media guidelines are insufficiently evidenced in the prevention of suicide [7]. Most importantly, gatekeeper training has been considered to be an effective suicide prevention strategy for young people by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In terms of gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention, social workers, caregivers, and churchmen should identify people with a high risk of suicidality and connect them with psychosocial support systems [8].

In Korea, evidence-based suicide prevention strategies have been developed as follows: The first suicide prevention program for the members of the Korean Medical Association was held in 2010. In addition, in terms of gatekeeper training, the Standardized Suicide Prevention Program for Gatekeeper Intervention in Korea was originally developed by the Korea Association for Suicide Prevention, under the support of the Life Insurance Philanthropy Foundation in 2011 [9]. Thus, “Suicide CARE” was developed for the early detection of danger signals of suicide completion, since there is a tendency to regard emotional suppression as a virtue of Korean traditional culture. The gatekeeper training program has been popularly referred to as “Bo-Deud-Mal (Bogo Deudgo Malhagi)” in Korean and translated to “Suicide CARE” (“Careful observation,” “Active listening,” and “Risk evaluation and Expert referral”) in English. “Suicide CARE” provides specific guidelines regarding gatekeeper intervention for people with a high risk of suicide. In addition, the gatekeeper training program has been divided into three parts according to the name as follows: “Careful observation” covers the detection of verbal and non-verbal signals for suicidal intents. “Active listening” aims to actively hear the cause of suicidal intention, and “Risk evaluation and Expert referral “ involves referring suicidal persons to psychiatric professionals. After the first demonstration of “Suicide CARE” in January 2013, an executive committee, which consisted of its developing team, was established by the Korea Suicide Prevention Center. Based on the principle that any individual could complete the program free of charge, education was mainly provided through community mental health welfare centers nationwide. The instructors were limited to mental health professionals with more than two years of suicide prevention work experience, and they completed a 2-day course of “Suicide CARE” with faculty supervision. Instructors were provided with instructor manuals with detailed information on contents, and gatekeepers were provided with the contents of workbooks, video clips, and role plays. It was designed to simulate the experience of the activity. The certificates of completion for “Suicide CARE” were downloaded through the website of the Korea Suicide Prevention Center (adapted from http://www.spckorea.or.kr/index.php). By 2019, 1.2 million individuals had completed life-saving education [10].

In addition, the gatekeeper training program was revised to provide individually differentiated programs focusing on specific groups, including young people, office workers, and the army, navy, and air forces, under the support of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, in 2014. The revised version number of the gatekeeper training program was marked as 1.6 (not 2.0) because the revisions made were modest. “Suicide CARE” version 1.6 consists of a workbook, transcript of the lecture, and video clips to improve gatekeeper training [11]. As shown in Figure 1, each part named “Careful observation,” “Active listening,” and “Risk evaluation and Expert referral” is represented by an individual image, in “Suicide CARE” versions 1.0 and 1.6, respectively [9,11]. A telephone survey of 800 people who had completed the educational course of the program in 2013 reported that the gatekeeper’s intervention for suicide prevention could be favorably supported by “Suicide CARE” version 1.6 [10]. Owing to the considerable amount of time since its initial creation, it was required that “Suicide CARE” should be revised entirely. It is also necessary that the revised gatekeeper training program should be underpinned by current study findings and empirical knowledge. In addition, the gatekeeper training program must be revised based on psychological autopsy interview findings [12] in the most recent 5 years in Korea. Since suicide has been the most common cause of death among those in their 10s, 20s, and 30s, and the second most common among those in their 40s to 50s in Korea, it has been presumed that the development of age-group-based differentiated suicide prevention approaches is urgently needed. Thus, “Suicide CARE” was revised from version 1.6 to 2.0, between August 2019 and February 2020, by the multidisciplinary team including psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers. The revision has been mainly based on the numerous domestic and international gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention and the recent psychological autopsy findings of Korea. Therefore, in this paper, we aim to present the detailed revision process of “Suicide CARE” from version 1.6 to 2.0.

Image representing “Careful observation,” “Active listening,” and “Risk evaluation and Expert referral” in “Suicide CARE” versions 1.0 and 1.6. Adapted from “Suicide CARE” (Standardized Suicide Prevention Program for Gatekeeper Intervention in Korea) version 1.5 Workbook. Seoul: Korea Association for Suicide Prevention & Korea Suicide Prevention Center, 2014, according to the Creative Commons license. [9,13] From left to right, characterized images symbolize the “Careful observation,” “Active listening,” and “Risk evaluation and Expert referral” parts.

METHODS

Under the support of Korea Suicide Prevention Center, which is a designated agency of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, during the period from August 2019 to March 2020, “Suicide CARE” has been revised from version 1.6 to 2.0. The revision process consisted of: 1) reviews about domestic gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention, 2) reviews about international gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention, 3) reviews about psychological autopsy interview reports, 2018, and 4) reviews about feedback from persons who completed “Suicide CARE” version 1.6.

RESULTS

Domestic gatekeeper training programs

As shown in Table 1, the Korea Suicide Prevention Center has managed a registration system for domestic gatekeeper training programs to introduce evidence-based suicide prevention interventions [13]. In addition, the Korea Suicide Prevention Center has certified the evidence levels of domestic gatekeeper training programs. Thus, 68 different programs have been certified. The certification criteria are classified into SECTION 1, SECTION 2, and SECTION 3 as follows: SECTION 1 denotes the suicide prevention intervention in which the content and efficacy are evidenced by a structured empirical study (randomized controlled study or non-randomized controlled study). SECTION 2 denotes expert consensus-based interventions or recommendations in the general setting. SECTION 3 denotes interventions or recommendations in special settings (i.e., public awareness and promotion programs, education or training programs, protocols or guidelines, and screening tools). A review of the current domestic gatekeeper training programs reveals the following limitations: First, as shown in Table 1, most of the domestic gatekeeper training programs were certified as low-level. Among 68 different programs, 89.7% (n=61) were defined as SECTION 3, whereas 8.8% (n=6) were defined as SECTION 2. Only 1.5% (n=1) of the programs was defined as SECTION 1, according to the criteria of the Korea Suicide Prevention Center [16]. Second, it has been speculated that the domestic gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention are in a state of contention with many differing views. In addition, more than half of the programs were developed by institutions located in the National Capital region (i.e., Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi-do). Most of the domestic gatekeeper training programs are available only for targeted regional residents and not for non-targeted regional residents. Thus, to overcome these limitations, it has been suggested that a new domestic gatekeeper training program with a high level of evidence and a national range of availability should be developed. Most programs commonly focus on enhancing gatekeepers’ understanding of the risk and protective factors of suicide to connect highrisk suicidal persons with mental professionals early. In addition, all programs are free of charge. Herein, it has been proposed that the revised version of “Suicide CARE” should be supported by high-level evidence available nation-wide and focused on gatekeepers’ early detection and management of suicidal risk.

International gatekeeper training programs

Suicide Prevention Resource Center (SPRC), Resources and Programs (available from: http://www.sprc.org/resources-programs) [78] were searched from inception until October 30th, 2019. As shown in Table 2, we reviewed the international government-initiated suicide prevention programs, including the Office Worker Suicide Prevention Policy (World Health Organization), data from the Bureau of Labor in Quebec (Canada), Montreal police officer’s Together for Life (Canada), suicide prevention model for office workers (Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention), Victorian Work-Related Fatality Database (VWRFD) (Australia), MATES in Construction: construction worker suicide prevention (Australia), and others. In addition, we reviewed the international private corporate-initiated suicide prevention programs, including the Applied Suicide Intervention Skills Training (ASIST), Question, Persuade, Refer (QPR), Working Minds, and others. We extracted common factors, characteristics, and availability in Korean contexts from the international gatekeeper training programs. Reviews of the international gatekeeper training programs presented major considerations as follows: First, each of the international gatekeeper training programs has been developed to be used consistently with each of the special conditions for the countries. It has been concluded that most international gatekeeper training programs may be inconsistent with the particular conditions of suicide in Korea. Second, it has been assumed that the early detection of suicide risk signals should be an essential content of “Suicide CARE” version 2.0. Thus, the “Careful observation” part has been proposed as the most important portion in the revision process of “Suicide CARE” from version 1.6 to 2.0. Third, since most of the international gatekeeper training programs require a range of tuition fees, it is speculated that the fees can contribute to the main obstacles for educating and training gatekeepers. Thus, it was concluded that “Suicide CARE” should be distributed free of charge. Fourth, role play and group simulation are regarded as the main sections in many of the international gatekeeper training programs. Thus, it has been proposed that role-play or group simulation should be included in “Suicide CARE” version 2.0.

Psychological autopsy interview reports 2015–2018

The Korea Psychological Autopsy Center has published psychological autopsy interview reports, which present the clinical characteristics of 391 Korean suicide completers from 2015 to 2018, based on interviews with family survivors [12]. The contents for the psychological autopsy interview reports, 2015–2018, were also included in the revision of the “Suicide CARE.” Among 391 suicide completers, 92.3% (n=361) presented warning signals before suicide completion, whereas 6.1% (n=24) did not present warning signals. In addition, 1.5% (n=6) were not aware of the warning signals. In the 361 suicide completers who presented warning signs before death, alterations in verbal expression, behaviors, and emotions, 77.0% (n=278) were not recognized, whereas only 20.5% (n=74) were recognized. In addition, warning sign recognitions in 2.5% (n=9) was not evaluated.

The psychological autopsy interview reports classified suicide warning signals into three groups: verbal, behavioral, and situational signals. First, the verbal and behavioral signals for a total of 249 people who committed suicide from 2016 to 2018, were analyzed descriptively since the data from the suicide completers in 2015 did not contain specific contents. The specific suicidal signals were as follows: the verbal signals were classified into frequent mentions about suicide, homicide, or death (n=130, 52.2%), somatic complaints (n=120, 48.2%), expression of self-criticism (n=106, 42.6%), questioning on how to commit suicide (n=30, 12.0%), writing about death in letters, notes, etc. (n=40, 16.1%), expression of longing for the afterlife (n=30, 12.0%), and talking about people who committed suicide (n=19, 7.6%). The behavioral signals were classified into alterations in sleep (n=164, 65.9%), alterations in appetite (n=133, 53.4%), decreased concentration or indecisiveness (n=82, 32.9%), indifference to appearance management (n=82, 32.9%), disposing of the belongings (n=75, 30.1%), self-destructive behaviors or substance abuse (n=63, 25.3%), striving to improve interpersonal relationships (n=45, 18.1%), planning suicide (n=43, 17.3%), aggressive or impulsive behaviors (n=43, 17.3%), giving others the things they usually valued (n=19, 7.6%), and excessive collecting of poems, music, and movies related to death (n=12, 4.8%). Second, the situational signals for a total of 103 people who completed suicides in 2018 only were analyzed descriptively. Since situational signals for suicide can be multifactorial and complex, they were simply classified as mental health problems (n=87, 84.5%), occupation-related stress (n=70, 68.0%), economic problems (n=56, 54.4%), family-related stress (n=56, 54.4%), interpersonal relationship-related stress (n=40, 38.8%), spouse-related stress (n=35, 34.0%), physical health problems (n=34, 33.0%), lover-related stress (n=14, 13.6%), and learning-related stress (n=14, 13.6%). In terms of classification of the suicide commitment period, the warning signals three months before the suicide completion were alterations in emotion, alterations in appetite, alterations in sleep, disposing of the belongings, and loss of energy or interest. In addition, the warning signals one week before suicide completion were disposing of belongings, striving to improve interpersonal relationships, and aggressive or impulsive behaviors. Furthermore, in terms of classification of the life cycle, the suicide warning signals of young adults were learning, family and lover-related stress, loneliness, and absence of close relationships. In addition, the signals in middle-aged adults were economic stress and debt problems. Finally, the signals in the elderly were chronic physical diseases, unspecified somatic symptoms, and absence of interpersonal relationships.

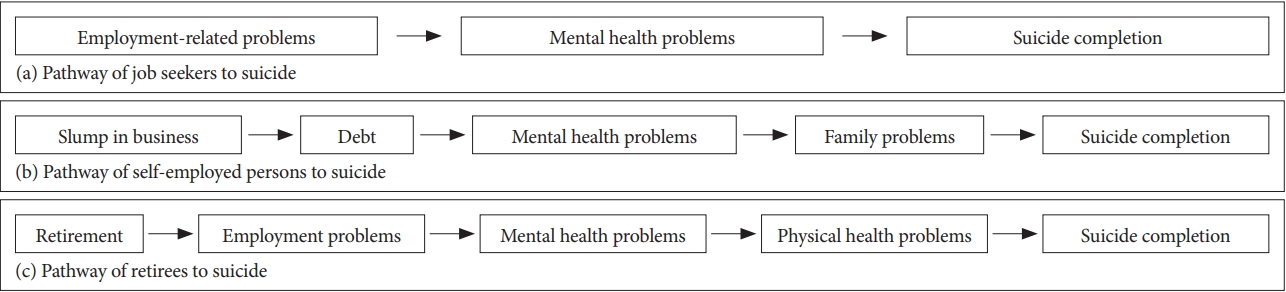

As shown in Figure 2, based on the psychological autopsy interview reports, the chronicled pathways to suicide completion of job seekers, self-employed persons, and retirees were conceptualized to improve the understanding of suicidal cases. Thus, by consensus of the developers for “Suicide CARE” version 2.0, life cycle-based example cases were selected from the conceptualized paths to suicide.

Feedback of persons who completed “Suicide CARE” version 1.6

From September 16 to October 4, 2019, a survey questionnaire that included difficulties in teaching, feedback about content and construction of each part, and feedback about instructor training courses was administered by persons who completed training of “Suicide CARE” version 1.6, and 66 persons responded to the survey questionnaire [82]. The responses were as follows: First, since many of the students for “Suicide CARE” version 1.6 felt bored, it has been proposed that a method to relieve boredom should be added in the new version. Thus, “Suicide CARE” version 2.0 is needed to fulfill a diversified demand for education according to age, sex, occupation, and other factors. In addition, the transcript of the lecture needs to be reduced, and the capability of educators needs to be increased in order to guarantee educators’ unconstrained lectures. Furthermore, the education time needs to be reduced to decrease the burden of educators and students. It has been proposed that weighting more important content can improve the efficiency of lectures. Second, it has been proposed that the contents of the adolescent version should be updated and added. Most of all, it is necessary to add the fact that suicide currently is the most common cause of death in adolescence. It is also necessary to add the fact that self-injury is a warning sign for suicide. Moreover, it is necessary to complement a method to improve the concentration of middle school students. Third, it has been proposed that “Suicide CARE” version 2.0, including the transcript of a lecture, should be differentiated according to the life cycle or occupation (i.e., adolescents, elders, office workers, public servants, soldiers, teachers, college students, etc.). It has been proposed that an advanced course should be developed in “Suicide CARE” version 2.0. In addition, it is necessary to diversify the scenarios of role-playing to improve the quality of the practical exercise for educators. Overall, the contents of the survey responses were consistent with the opinions of the developers for “Suicide CARE” version 2.0.

DISCUSSION

The developers of “Suicide CARE” version 2.0 planned to revise more than 70% of “Suicide CARE” version 1.6 based on the troubling suicide-related situation in Korea. Psychological autopsy interview reports showed that suicide completers express self-deprecation and show changes in sleep and appetite. Thus, the findings of the psychological autopsy interview reports were planned to be incorporated into video clip scenarios. It has also been planned that the characters of video clips include a job-seeker (aged 20–30, female), a self-employed person (middle aged, male), and a retired person (over 70 years old, male). Herein, from August 2019 to February 2020, the workbook, manuscript of lecture, and video clips of “Suicide CARE” were revised. Since “Suicide CARE” version 2.0 was developed based on extensive international literature reviews and the psychological characteristics of more than 300,000 Koreans, it is expected to enhance the effectiveness of gatekeeper training. In “Suicide CARE” version 2.0, educational video clips are regarded as an important component because it is a key medium that delivers the main contents of education to the trainee. Herein, as shown in Table 3, “Suicide CARE” has been updated from version 1.6 to 2.0 [114]. In terms of a utilization plan, from now on it is expected that all gatekeeper education programs be conducted using “Suicide CARE” version 2.0. Moreover, it is expected that “Suicide CARE” version 2.0 be positioned as the basic framework for many developing gatekeeper training programs for suicide prevention in Korea in the near future. However, owing to the limited production cost, there has been a limit on capturing visual quality that can convey empathy and emotion along with educational content. In the future, when revising “Suicide CARE” version 2.0 or when creating a specialized program for other special roles, such as firefighters and soldiers, it is necessary to reflect sufficient production costs in the production of the video when forecasting a budget.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Prof. Se-Won Lim for his dedication to the development of “Suicide CARE” versions 1.0 and 1.6. This work was supported by the Standardized Suicide Prevention Program for Gatekeeper Intervention in Korea, version 2.0, development grant from the Korea Suicide Prevention Center. This work was also supported by the Korea Psychological Autopsy Center.

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hwa-Yong Lee, Hong Jin Jeon, Jong Woo Paik, Kang Seob Oh. Funding acquisition: Hwa-Yong Lee. Investigation: all authors. Projected administration: all authors. Writing—original draft: Seon-Cheol Park, Kyoung-Sae Na, Hwa-Young Lee. Writing—review & editing: all authors.