Association between the Arylalkylamine N-Acetyltransferase (AANAT) Gene and Seasonality in Patients with Bipolar Disorder

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Bipolar disorder (BD) is complex genetic disorder. Therefore, approaches using clinical phenotypes such as biological rhythm disruption could be an alternative. In this study, we explored the relationship between melatonin pathway genes with circadian and seasonal rhythms of BD.

Methods

We recruited clinically stable patients with BD (n=324). We measured the seasonal variation of mood and behavior (seasonality), and circadian preference, on a lifetime basis. We analyzed 34 variants in four genes (MTNR1a, MTNR1b, AANAT, ASMT) involved in the melatonin pathway.

Results

Four variants were nominally associated with seasonality and circadian preference. After multiple test corrections, the rs116879618 in AANAT remained significantly associated with seasonality (corrected p=0.0151). When analyzing additional variants of AANAT through imputation, the rs117849139, rs77121614 and rs28936679 (corrected p=0.0086, 0.0154, and 0.0092) also showed a significant association with seasonality.

Conclusion

This is the first study reporting the relationship between variants of AANAT and seasonality in patients with BD. Since AANAT controls the level of melatonin production in accordance with light and darkness, this study suggests that melatonin may be involved in the pathogenesis of BD, which frequently shows a seasonality of behaviors and symptom manifestations.

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BD) is chronic psychiatric disorder characterized by episodic changes in mood and energy level [1]. BD has a high heritability, close to 80% [2,3]. However, because of the heterogeneity of the biological basis and complexity of genetic architecture, there have been limited findings in genetic studies [4,5]. Therefore, alternative approaches adopting specific clinical features and biological markers as phenotypes for genetic studies were suggested [6-8].

Organisms have evolved innate biological clocks that oscillate with the environmental cycles of day and night (circadian rhythm) and photoperiod change (seasonal rhythm) for adaptation [9-11]. This process is also important for humans to adjust to external cues [12,13], but abnormally exaggerated or dampened rhythmic behavioral changes have been observed in some mental disorders [14,15]. In BD, the variation of biological rhythms, such as seasonal mood, behavioral changes, or circadian rhythm abnormalities have been suggested as distinctive clinical characteristics [16-18]. Although abnormalities in biological rhythms are more prominent during episodes, they are also identified in euthymic state BD and regarded as lifetime traits. A seasonal pattern is common in BD, even among treated patients whose seasonal fluctuations may have been modified by such treatment. In addition, BD who not experienced either seasonal manic or depressive episodes, also reported to have higher scores for seasonal variation in mood and behavior when compared to the general population or patients with depression [19,20]. Climatic conditions may trigger BD symptoms or episodes [21-23] and antimanic drugs have been known to stabilize circadian rhythms [24,25]. Also, BD with seasonal depressive episodes or evening preference have been reported to be associated with other specific clinical profiles, e.g., bipolar II disorder subtype, comorbid eating disorders and premenstrual syndrome, more relapses and rapid cycling [18,26-29].

Melatonin is a neurohormone secreted from the pineal gland during the hours of darkness. It falls rapidly with light onset. Arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT) is a key regulatory enzyme in the melatonin biosynthesis pathway, which converts serotonin to N-acetylserotonin. N-acetylserotonin is converted to melatonin by acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase (ASMT) [30]. Oscillating levels of activated AANAT result in the rhythmic synthesis and secretion of melatonin [31]. Seasonal photoperiod-induced changes in melatonin secretion have widereaching effects on seasonal animal physiology and behavior, as the MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors (encoded by MTNR1a and MTNR1b) are distributed widely throughout the body, including the central nervous system, heart, endocrine system, and immune system [11,32].

Considering the abnormal biological rhythms and melatonin levels observed in patients with BD [17,18,33] and the role of melatonin in diurnal and seasonal changes [11,32], melatonin seems to be related to the biological mechanisms that develops the clinical characteristics of the subgroup of BD. Genetic studies for BD focusing on genes in the melatonin pathway reported mixed results [33-36]. A genetic heterogeneity of BD may be one reasons for this discrepancy. There have also been association studies using biological rhythm disruption as an alternative phenotype in BD. Geoffroy et al. [37] reported a negative finding in their investigation of the association between seasonal depressive episodes and the circadian genes in the melatonin pathway. Other study regarding sleep patterns of BD and healthy controls showed an association between the ASMT variant and the inter-day stability of sleep [38].

We hypothesized that patients with BD with abnormal biological rhythms as a lifetime trait are likely to have a specific genetic underpinning, especially related to the melatonin pathway. This study investigated the association between the melatonin pathway genes, the circadian preferences, and seasonal mood and behavior changes in BD.

METHODS

Subjects

We recruited clinically stable patients who met the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for BD (n=324), including bipolar I disorder (n=182), bipolar II disorder (n=134) and BD not otherwise specified (n=8) between 18 and 60 years of age from the outpatient and inpatient units of the Samsung Medical Center (n=148) and the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (n=176) in South Korea. Board-certified psychiatrists who had at least one year of research experience examined the participants’ psychiatric diagnoses using the DSM-IV criteria with either the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) [39] or the Korean version of the Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS) [40]. SCID was used at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital and DIGS was used at the Samsung Medical Center. No significant difference in terms of demographic characteristics was detected between participants evaluated using SCID and DIGS. We excluded participants if they could not clearly remember their lifetime traits due to illnesses. Moreover, to prevent the effect of current mood state or medication in evaluating their lifetime characteristics, we included participants after their medication had been stabilized. All participants were under the standard pharmacological treatment, including mood stabilizers (lithium, valproate, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine) or atypical antipsychotics (quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone, aripiprazole, and ziprasidone). We excluded those with mental retardation, substance abuse, medical illnesses, or long-term use of hormonal agents known to affect mood. Because sustained social rhythm can deeply affect the biological rhythm [41], we also excluded nightshift workers as participants. We obtained written informed consent from all subjects after a complete explanation of the study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Samsung Medical Center (IRB No. 2012-09-056) and the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-1105/128-008).

Measurements of phenotypes

We measured circadian preference by using the standardized Korean version of the Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM) [42,43], containing 13 questions concerning what time participants preferred to go to bed, wake up, and perform specific activities. The sum of the answers to these questions yielded a single score to represent the level of circadian preference (range, 13–55), with lower scores indicating a stronger evening preference. We measured seasonality with Seasonal Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SPAQ) [44] containing 6 items to measure seasonal variations in sleep, social activity, mood, weight, appetite, and energy level. The Korean version of the SPAQ that was translated into Korean was used with the permission of the original author. The translation and validation process for this scale has been described in our previous study [45]. We used the sum of individual item scores, each on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (no change) to 4 (extremely marked change) to indicate a global seasonality score (GSS). Based on the criteria of Kasper et al. [46,47] for seasonal affective disorder (SAD) and subsyndromal SAD, and a GSS of 9 or greater, we designated scores with a subjective rating of having at least mild difficulty with seasonal changes [on a 6-point scale from 0 point (no difficulty) to 5 points (a disabling difficulty); 1 points=mild] or a GSS of 11 or higher as having significant seasonality. We assigned both seasonality and circadian preference on a lifetime-basis.

SNP selection and genotyping

We isolated a genomic DNA sample from peripheral blood leukocytes by using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We produced the genotype data by using the Korea Biobank Array Chip (K-CHIP), version 1.0 from the K-CHIP consortium. The K-CHIP, consisting of about 833K SNPs for the whole genome, was designed by the Center for Genome Science, Korea National Institute of Health, Korea (4845-301, 3000-3031). According to the Affymetrix Axiom® 2.0 Assay User Guide, the K-CHIP assay was conducted by Axiom® 2.0 Reagent Kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which contains a series of reactions including amplification, fragmentation, hybridization, and ligation. After ligation, we stained the reaction product, imaged and analyzed it for genotype reading by using the Genotyping ConsoleTM Software (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). We produced the genotype data for approximately 790K SNPs after having checked quality control for the samples.

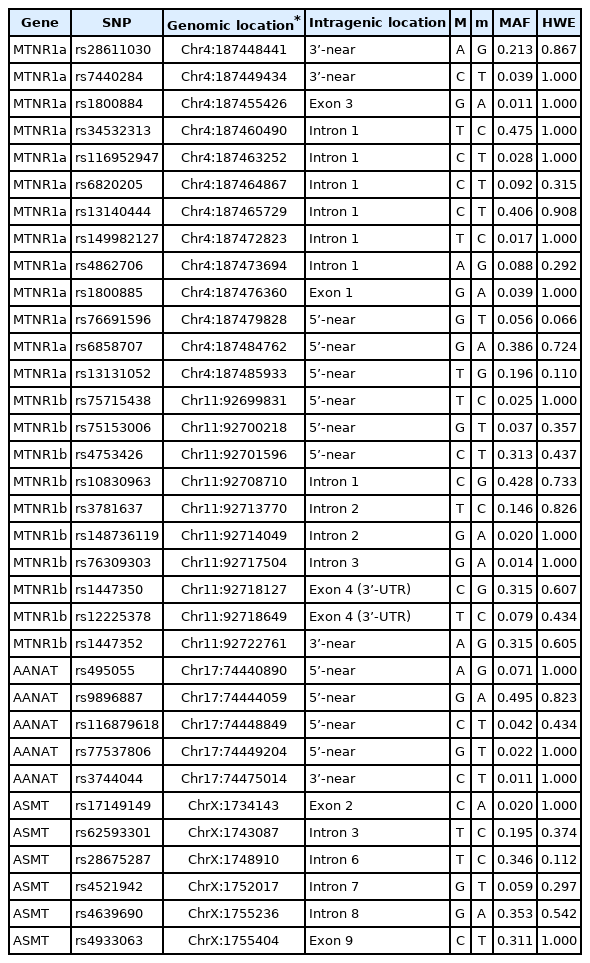

We selected four melatonin related genes (MTNR1a, MTNR1b, AANAT, ASMT). We explored single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within 10 kilobase pairs upstream and downstream from the coding and regulatory region of each of the genes. The former three genes are located in autosomes, and the ASMT is located in the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) of sex chromosomes. It had previously been suggested that these are linked to BD [48]. We included 34 SNPs with minor allele frequencies (MAF) greater than 1%, and genotype call rates >97% with the associated analyses. Table 1 summarizes the localization of the studied SNPs. To confirm the reliability of the genotyping method using the K-CHIP, we analyzed all SNPs with cluster plots. Four selected SNPs (rs34532313 on MTNR1a, rs10830963 on MTNR1b, rs9896887 on AANAT, and rs4639690 on ASMT) that showed the highest MAF for each gene were re-genotyped for 48 random samples by sequencing reaction using ABI PRISM® BigDye Terminator v 3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The concordance rate of genotype data between sequencing and assay using the array Chip was 99.5%.

Statistical analyses

We checked the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium with the Fisher’s exact test for genotype analysis. We observed no significant deviation in any of these SNPs (Table 1). We evaluated the genotype associations between the selected SNPs and each phenotype by logistic and linear regression analysis, with age and sex as covariates. We considered the additive genetic models based on the minor alleles of each SNP. We controlled for experimental type I errors by using Bonferroni correction, covering all included SNPs (corrected p=0.05*SNP number). We did the statistical analyses with the R program, v.3.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and PLINK, v. 1.9 (www.cog-genomics.org/plink/1.9) [49].

We imputed genes that have a significant variant in the above process by using the reference panel of the EAS data from the 1000 Genomes Project Integrated Phase 3 Release. Likewise, we included SNPs within 10 kilobase pairs upstream and downstream from each gene. The data was phased using SHAPEIT (v2.837) [50] and imputed using IMPUTE2 (2.3.0). We selected variants with a high imputation quality (‘info’ score >0.5) [51]. We subsequently analyzed imputed SNPs with minor allele frequencies (MAF) greater than 1%, and genotype call rates >97% for association by using PLINK v.1.9. We used the Haploview software 4.0 [52] to estimate and plot pairwise linkage disequilibrium (LD) measures of SNPs that were included in associated analyses in this study. The LD blocks were defined according to Gabriel criteria [53].

RESULTS

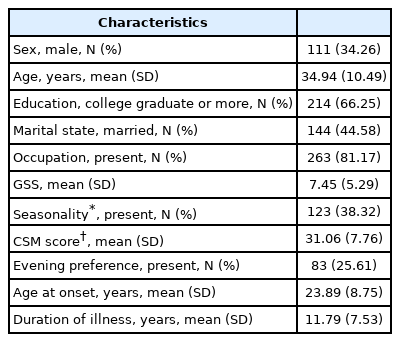

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n=324) were demonstrated in Table 2. About 38% (n=123) of the participants presented with seasonality and 25% (n=83) presented with evening preference based on the cut-off value derived from the Korean general population [43]. Patient with seasonality demonstrated much younger age (p=0.04), earlier age of onset (p=0.02) and no difference in bipolar I or II subtypes. The earlier onset age in BD with seasonality was consistent with other previous studies (Table 3) [26,37].

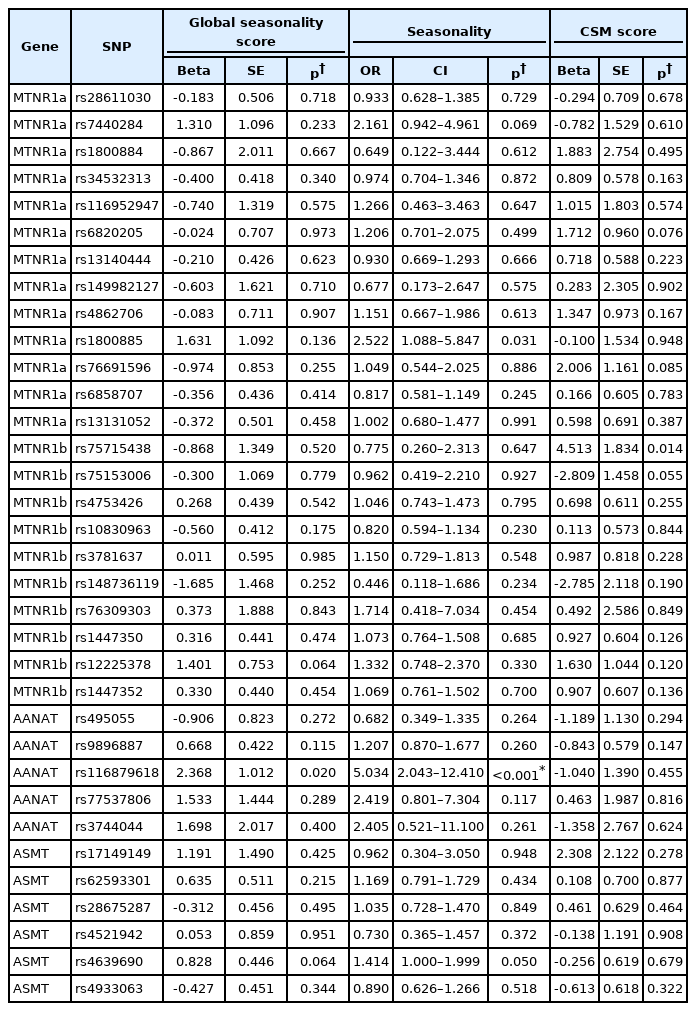

Single marker analysis identified nominal associations (uncorrected p<0.05) between seasonality and three SNPs in melatonin pathway genes. These were rs116879618 located in AANAT (p=0.0004), rs1800885 in MTNR1a (p=0.031), and rs4639690 in ASMT (p=0.0497). After adjusting for multiple testing by using the Bonferroni correction, the association remained significant for rs116879618 in AANAT (corrected p=0.0151). GSS showed nominal associations with rs116879618 located in AANAT (p=0.0199), but it did not remain significant after multiple test corrections. Circadian preference showed a nominal association (uncorrected p<0.05) with rs75715438 in MTNR1b (p=0.0144), but it did not remain significant after adjusting multiple testing (Table 4). All analyses data are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement).

Summary of association analysis of SNPs in melatonin pathway genes and seasonality and circadian preference of patients with bipolar disorder

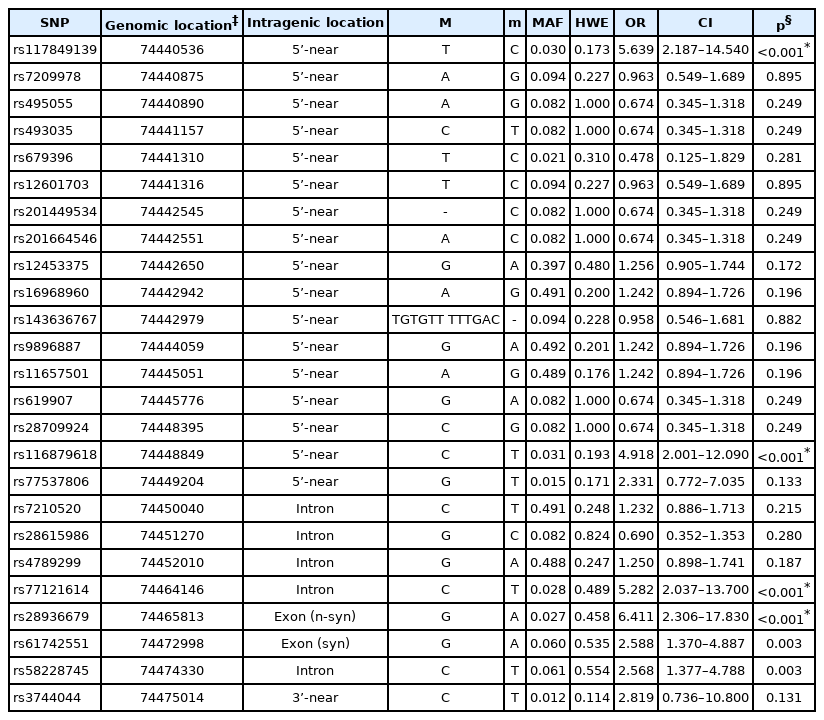

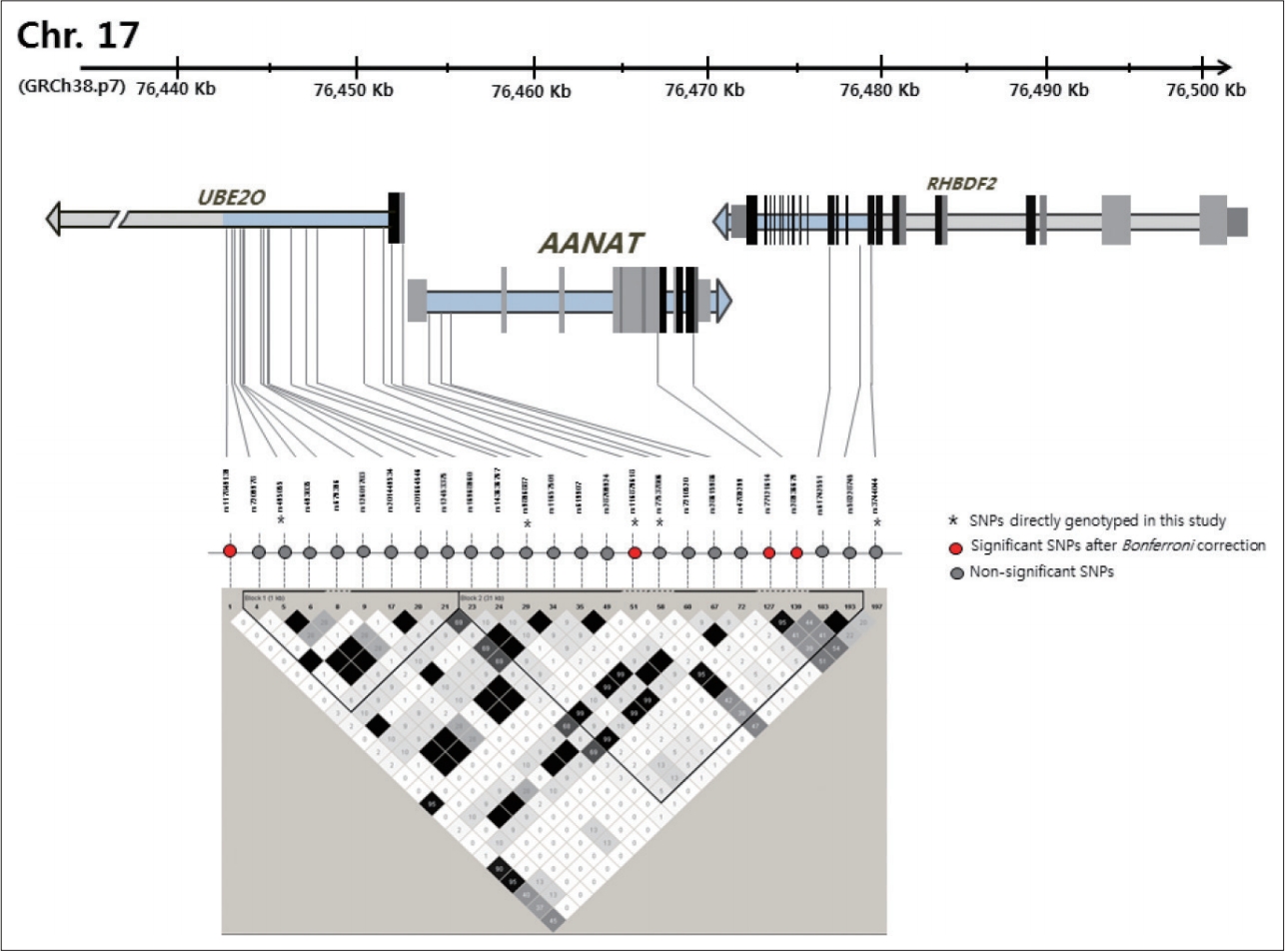

Since AANAT showed significant association with BD, we performed additional imputation analysis. We generated the genotypes of 20 additional SNPs through imputation following quality control, and we conducted an associated analysis for each SNP and seasonality. Figure 1 presents the locations of the AANAT SNPs and their linkage disequilibrium block. An additional five SNPs showed a nominal association, and three SNPs, rs117849139, rs77121614, and rs28936679 (corrected p=0.0086, 0.0154, and 0.0092) showed a significance association following multiple test corrections. Among these SNPs, rs28936679 is a nonsynonymous (missense) variant in exon 1 (Table 5). Supplementary Table 2 (in the online-only Data Supplement) presents detailed information about the imputed SNPs and the statistical data.

Scaled graphical representation of the 10 Kb genomic region surrounding the AANAT including association analysis results. Relative positions of SNPs directly genotyped in this study and imputed SNPs are presented. Coding exons of the genes in the regions are shown in gray, noncoding exons in black. SNPs that showed significant association with seasonality of BD are highlighted in the red circle. Bottom of diagram, there is the LD pattern of the region determined and visualized using the Haploview, and LD blocks were defined according to Gabriel criteria[53]. SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism, BD: bipolar disorder, LD: linkage disequilibrium.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate whether the melatonin pathway genes are associated with biological rhythm changes in patients with BD. Assuming that specific clinical presentations have a more homogeneous genetic underpinning, we evaluated the genetic association of phenotypes reflecting the circadian and seasonal rhythms with the melatonin pathway genes as functional candidate genes.

In a previous study, BD patients demonstrated a hypersensitive pineal response to ocular light exposure when compared to a control, independent of the disease state [54]. Bipolar I disorder showed a lower baseline melatonin level and a lower nadir melatonin level on the light night and a greater amplitude of variation in melatonin secretion than did the controls on the dark night [55]. These studies and the result of the current study support the possibility that the melatonin pathway genes are involved in the exaggerated biological rhythm changes in BD.

Four variants in AANAT, ASMT, MTNR1a, and MTNR1b have been nominally associated with seasonality and circadian preference. Following correction for multiple testing, the rs116879618 in the AANAT remained significantly associated with the seasonality of BD. In past studies, genomewide linkage analyses with bipolar families have shown that the 17q25 region, including the AANAT, is linked to BD [56-58], and associated analyses with the bipolar population shows polymorphism of AANAT being associated with BD [34]. But some studies failed to find a significant result [35,36]. The rs116879618, which appeared to be significantly associated with the seasonality of BD in the current study, has not been reported to be significantly associated with BD or any other psychiatric disorders. Its clinical significance was not well defined, but it is located in 5’-UTR of the AANAT and may influence the regulatory function of this region. The AANAT has been labeled the “timezyme” [59] because of its role in the timing of melatonin production by the pineal gland along with light and darkness. Activity increases 10 to 100 fold at night, causing an increase in the production and the release of melatonin, and in response to light, it shows rapid degradation, thereby reducing the synthesis of melatonin [60,61]. The AANAT regulatory regions enabled the cAMP to control rapid activation and degradation switching by phosphorylating the Ser/Thr residues in the PKA/14-3-3 motifs [59].

Following imputation, the rs28936679 in the exon of AANAT also showed an association with the seasonality of BD. The rs28936679 is a nonsynonymous (missense) variant in the AANAT exon1, which participates in an amino acid substitution from alanine to threonine. Because of different chemical characteristics, such as the structure and polarity between these amino acids, the activity of AANAT might be affected by this substitution [62]. This SNP was also reported to be related to delayed sleep phase syndrome [62].

Notably in current study, the variant of AANAT was related to seasonality rather than circadian preference. A previous study based on the general population suggested that genetic variants may also contribute to the seasonality phenotype that is similar to the current study in some instances [63]. The suprachiasmatic nuclei regulate seasonal rhythmicity by perceiving and encoding changes in day length and transmitting them to the pineal gland, where they regulate melatonin production [11,64]. In animal studies, when entrained to a long photoperiod, the light-induced decrease in AANAT is advanced by an earlier dawn, whereas the dark-induced increase in AANAT is delayed by a later dusk. As a result, daily melatonin secretion is compressed during the summer and prolonged during the winter [65,66]. Therefore, the variants of AANAT can cause change in the normal seasonal rhythm, and could affect the seasonality of BD.

This study has several limitations. First, since it did not include normal control subjects, we are not sure if the current study’s findings are confined to BD or if they could be generalized in the normal population. Second, we included only four genes that directly participate in melatonin synthesis and action. Some other genes that may indirectly affect melatonergic function were not evaluated. Further studies that include more related genes and that cover genetic interactions are needed. Third, although night-shift workers were excluded from these subjects, we could not completely adjust for the effect of other social environments that could affect the individual’s lifestyle and sleep–wake cycle. Finally, current study showed an association between subgroup of BD patient and a melatonin pathway gene, but it is unclear whether this gene causes BD. In order to reveal this causality, future studies using methods such as Mendelian randomization are needed.

This study demonstrated an association between a genetic variation in AANAT and seasonality in BD. Further studies on the biological mechanisms of melatonin on the seasonality of BD are needed.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2020.0436.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Original Technology Research Program for Brain Science through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) [No. 2019M3C7A1030624].

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: So Yung Yang, Kyung Sue Hong, Ji Hyun Baek. Data curation: Kyung Sue Hong, Youngah Cho, Yujin Choi, Kyooseob Ha, Ji Hyun Baek. Formal analysis: So Yung Yang, Yongkang Kim, Taesung Park. Funding acquisition: Kyung Sue Hong. Investigation: Eun-Young Cho. Methodology: So Yung Yang, Kyung Sue Hong. Project administration: Kyung Sue Hong. Software: Yongkang Kim, Taesung Park. Supervision: Kyung Sue Hong. Validation: Kyung Sue Hong, Ji Hyun Baek. Visualization: So Yung Yang, Eun-Yung Cho. Writing—original draft: So Yung Yang, Kyung Sue Hong. Writing—review & editing: So Yung Yang, Kyung Sue Hong, Ji Hyun Baek.