Clinical Characteristics Associated with Suicidal Attempt and Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in Korean Adolescents

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the association between mood and anxiety symptoms and suicidal attempt (SA) and/or non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescents seeking mental health services. We also tested predictors of SA and NSSI.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 220 adolescents who completed psychological assessment in clinical sample. Participants did the Adolescent General Behavior Inventory (A-GBI) and Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI). SA and NSSI were assessed retrospectively by interview. The caregiver of participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) for themselves.

Results

17% of total participants had a history of SA, and 24% experienced NSSI. Both SA and NSSI were more common in girls. The score of depressive subscale on A-GBI was higher in adolescents with SA than those without. The participants with NSSI showed higher scores on CDI and depressive subscale on A-GBI than those without. SA was associated with maternal BDI and history of NSSI; female sex, depressive subscale on A-GBI, and history of SA with NSSI.

Conclusion

Our study found that NSSI and SA are strongly associated in adolescents. Female sex and depressive symptoms of the adolescents were also significantly associated with NSSI in Korean adolescent. Findings are consistent with patterns in other countries.

INTRODUCTION

Suicidal attempt (SA) is a nonfatal self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior [1]. SA in adolescents is assumed as a shared endpoint of chronic problems, like depressive disorder, substance abuse and stressful events [2]. The risk factors for SA known to as male sex, low socioeconomic status, parental separation, divorce or death, parental mental disorders, mental disorder as depression, and substance misuse in adolescence [3]. SA has been used as a clinical marker for risk of completed suicide, because it is well known that prior SA is one of the most effective predictors for suicide completion [4]. In epidemiological samples, 6% of US high school students report recent SA, and 5% of adolescents age 12–18 years in Korea also reported of previous SA at least once [5,6]. Especially in Korea, adolescent SA is an urgent issue as suicide is the leading cause of death in 10–19 years old and the rate of completed suicide has been increasing over the last decade [5,7].

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the direct, intentional destruction of one’s own body tissue using various method (e.g., cutting, hitting, burning) without suicidal intention [8]. Lifetime prevalence of NSSI has been reported as up to 26% in adolescents, which means a quarter of adolescents self-injured of themselves at least once in their lifetime [9]. The risk factors for NSSI were also various: early to mid-adolescence, female sex, social or medial contact with NSSI, dysfunctional relationship as bullying, and adverse event on childhood [10]. Adolescents with NSSI tend to have psychiatric diagnoses, including major depressive disorder, substance use disorder or personality disorders, and are more likely to admit attempting suicide [11]. Even after cessation of NSSI, the risk for long-term mental disorder and suicidality has remained in individuals [10]. NSSI has a crucial impact on families and communities and incurs a substantial societal cost burden [12,13]. Therefore, clinical attention is needed to develop prevention and management strategies.

SA and NSSI have been differentiated in terms of intention, repetition, and lethality [14]. However, these behaviors also have strong association and share common risk factors, including sociodemographic and educational factors, individual negative life events and family adversity, and psychiatric and psychological factors [3]. Several researchers further have concluded that NSSI is a strong risk factors for suicidal attempts [11,15].

Because of these clinical aspects in both SA and NSSI in adolescence, it is important to identify associated factors and predictors of SA and/or NSSI to provide appropriate interventions. However, most previous studies which evaluated the risk factors for suicide attempt or NSSI are from Western cultures. Moreover, most scales assessing the risk of suicide attempt or NSSI are focused on adults and there are only a few scales to assess the risk of suicide attempt and/or NSSI in children and adolescents [16-18]. This is a glaring omission given that the rates of suicide are actually much higher in Korea and Japan than in the USA or Western Europe [19,20], making it imperative to understand whether the risk factors and correlates are similar.

Thus, the primary goals of this study were to examine demographic and clinical aspects of SA and NSSI of Korean youth and to evaluate the predictive factors for SA and/or NSSI, including mood and/or anxiety symptoms of adolescents as well as their caregivers.

METHODS

Participants and study design

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years who completed psychological assessment for emotional problems from October 2011 to December 2018 through the Department of Pediatric Psychiatry, Asan Medical Center in Seoul, Korea. Participants were excluded if they met one or more of the following criteria: 1) suspected intellectual disability or an intelligence quotient (IQ) score of lower than 80; 2) diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder; 3) past and/or current history of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorder; 4) presence of seizure or other neurological disorders; 5) omitted more than 10% of each items of Adolescent General Behavior Inventory (A-GBI); and 6) clinical information not available. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective study design (IRB No. 2019-0129).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis was confirmed retrospectively based on the reported symptoms or diagnosis of the medical records. Board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists (n=6) first interviewed youth and their caregivers separately, evaluated, and recorded mood and other psychiatric symptoms. During psychological assessment, clinical psychologists also interviewed youth and their caregivers separately. The psychological assessment took 3–4 hours per each participant. Mood disorders and other disorders were assessed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) [21]. Participants were classified into three groups: 1) Bipolar disorder group, 2) Depressive disorder group and 3) Non-mood disorder group. Bipolar disorder group included bipolar depression, bipolar mania, and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BD-NOS). Depressive disorder group included unipolar depression, dysthymia, and adjustment disorder with depressed mood. Participants without any mood disorders were classified in Nonmood disorder group.

Psychological assessment

The adolescents completed the Korean version of the 76-item A-GBI [22], Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [23], and Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) [24]. The caregivers of the participants completed Korean version of the Parent General Behavior Inventory-10-item Mania Scale (P-GBI-10M) [25] for their children and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [26] for themselves. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the A-GBI, CDI, RCMAS, and BDI were previously determined [27-30]. In one or two sessions of psychological assessment, the psychologist explored symptoms and other psychiatric problems of adolescent and interviewed about family relationships. In addition, the adolescent completed not only previously described self-reported tests and Bender Gestalt Test or Visuo-Motor Integration, House-TreePerson Test, Kinetic Family Drawing, Kinetic School Drawing Rorschach Test, Thematic Apperception Test, and The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory with psychologist.

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Age and gender were noted through medical records. Previous SA and NSSI were assessed reviewing medical records using the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment (C-CASA) [31], a standardized suicidal/non-suicidal behavior rating system. According to C-CASA, self-injurious behaviors can be classified with eight steps, from completed suicide to non-suicidal injuries or accidents, and “not enough information.” The C-CASA category of self-injurious behavior, no suicidal intent” was the operational definition for NSSI.

The number of previous SA and NSSI events was categorized with (a) 0, (b) 1, (c) 2–5 or (d) > 5 for both past year and lifetime history intervals. The method used for SA was categorized as follows: (a) drug intoxication, (b) hanging, (c) falling down, (d) drowning, (e) CO poisoning, or (f) other, and NSSI was categorized as follows: (a) cutting, (b) hitting, (c) scratching, (d) drug intoxication, (e) more than two ways or (f) other.

Statistical analyses

Independent t-test were used for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables to compare demographic and clinical variables by dividing groups according to the presence of previous SA and NSSI histories. Previous SA and NSSI histories were evaluated by lifetime histories of SA and NSSI. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Bonferroni correction compared demographic and clinical characteristics, among Bipolar, Depressive and Non-mood disorder groups. Logistic regression analysis determined the incremental effects of psychological assessments and other clinical characteristics on SA and NSSI. Statistical analyses used SSPS 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined at a p value of less than 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

From October 2011 to December 2018, 392 adolescents completed psychological assessments and 172 were excluded: 62 didn’t answer more than 10% of A-GBI items; 61 with FSIQ below 80; 29 with a history of psychotic disorders; 13 with comorbid neurological disorders; six with comorbid autism spectrum disorder; one with missing clinical information.

Two-hundred and twenty adolescents (age 15.3±1.6 year, 90 males) were finally included with this study. Within those 220 participants, 28 adolescents were diagnosed with bipolar depression, four with bipolar mania, 21 with BD-NOS, 123 with unipolar depression, three with dysthymia, two with both unipolar depression and dysthymia, and six with adjustment disorder with depressive mood. Thirty-three adolescents did not have any mood disorders, as they were diagnosed with anxiety disorders, somatic symptoms disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), tic disorder, eating disorder, conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder. As a result, 53 adolescents were included in the bipolar disorder group (age 14.6±1.8 years, 12 males), 134 in the depressive disorder group (age 15.4±1.5 years, 59 males) and 33 in the non-mood disorder group (age 15.4±1.7 years, 19 males).

Table 1 reports the demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants according to the diagnosis. Adolescents in the depressive disorder group were older than those in the non-mood disorder group (F=3.55, p=0.030). There were more girls in the bipolar disorder group than the depressive disorder and non-mood disorder groups (χ2=11.66, p=0.003).

FSIQ, P-GBI-10M, and maternal BDI were not significantly different between the groups, but scores of RCMAS (F=9.67, p<0.001), CDI (F=10.97, p<0.001) and depressive subscale of A-GBI (F=15.53, p<0.001) were higher in both the depressive and bipolar disorder groups than the non-mood disorder group. In addition, the hypomanic/biphasic subscale of A-GBI were significantly different across all three groups, highest in Bipolar disorder group and lowest in Non-mood disorder group (F=10.56, p<0.001)

Of 220 participants, 17% of adolescents had history of SA (n=37, age 15.7±1.4 year, 7 males) and 24% had experienced NSSI (n=52, age 15.8±1.5 year, 8 males); 9% had a history of both SA and NSSI (n=19, age 15.8±1.4 year, 1 male). One-hundred and fifty adolescents did not have any history of SA or NSSI (age 15.0±1.7 year, 76 males).

SA

Among 37 adolescents with history of SA, the number of attempts was 1 in 27 adolescents, 2–5 in 9, and more than five in one participant. The most favored method of SA was drug intoxication (18 participants), followed by falling (9 participants), hanging (6 participants) and others (4 participants).

We compared demographic characteristics, diagnosis, and psychological assessments between groups with and without SA in Table 2. Gender distribution (χ2=8.90, p=0.003) and diagnosis (χ2=8.28, p=0.016) were significantly different, but there were no more significant differences after correction for multiple comparisons. RCMAS (t=2.03, p=0.044), CDI (t=2.30, p=0.023), depressive (t=4.30, p<0.001) and hypomanic/biphasic subscales (t=2.86, p=0.005) of A-GBI and maternal BDI (t=2.81, p=0.005) were higher in the participants with previous SA. After multiple comparison adjustment, only the depressive subscale of A-GBI remained significant.

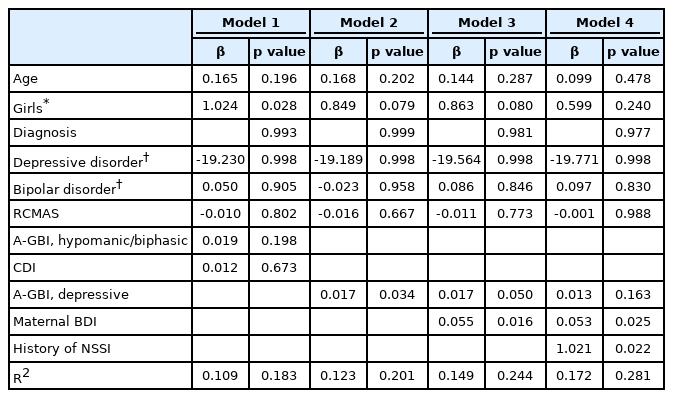

Table 3 presents the logistic regression analyses. Model 1 entered age, gender, diagnosis, RCMAS, A-GBI hypomanic/biphasic subscale and CDI; only gender was significantly associated with SA (β=1.024, p=0.028). In model 2, age, gender, diagnosis, RCMAS and A-GBI depressive subscale were included. In model 3 added maternal BDI and model 4 added history of NSSI were added to model 2, respectively. Maternal BDI (β=0.053, p=0.025) and history of NSSI (β=1.021, p=0.022) were significantly associated with previous SA in final model. A-GBI depressive subscale was statistically significant in model 2 (β=0.017, p=0.034), but not in model 3 and 4.

NSSI

Fifty-two adolescents reported a history of NSSI, while 39 self-mutilated themselves more than five times, 9 only once and 4 with 2–5 times. Participants used cutting most frequently (44 participants), followed by scratching (11 participants), drug intoxication (5 participants) and other methods (4 participants, including banging and using staplers). Twelve adolescents reported they used two or more methods for NSSI.

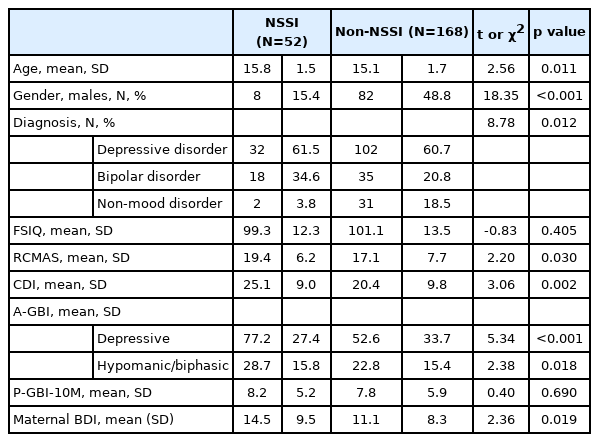

Table 4 shows the comparison of demographic characteristics, diagnosis and psychological assessments between participants who had a history of NSSI versus those who did not. Age (t=2.56, p=0.011), gender (χ2=18.35, p<0.001) and diagnosis (χ2=8.78, p=0.012) were significantly different, but after multiple comparison adjusted only gender was significantly different, with more girls in the NSSI group. Adolescents who self-mutilated themselves tended to have higher RCMAS (t=2.20, p=0.030), CDI (t=3.06, p=0.002), depressive (t=5.34, p<0.001) and hypomanic/biphasic subscale (t=2.38, p=0.018) of A-GBI and maternal BDI scores (t=2.36, p=0.019). The CDI and depressive subscale of A-GBI remained significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with and without Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (NSSI)

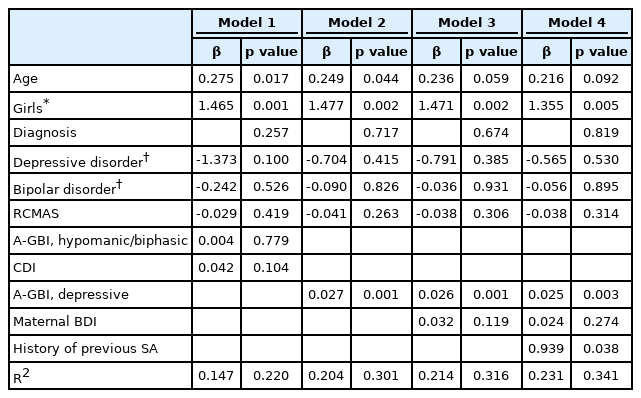

Table 5 displays the results of logistic regression analysis. Model 1 entered age, gender, diagnosis, RCMAS, A-GBI hypomanic/biphasic subscale, and only gender was significantly associated with NSSI (B=1.465, p=0.001). Model 2 included age, gender, diagnosis, RCMAS and A-GBI depressive subscale, and model 3 added maternal BDI, and model 4 added history of SA (i.e., matching the models for SA). Gender (B=1.355, p=0.005), A-GBI depressive subscale (B=0.025, p=0.003) and history of SA (B=0.939, p=0.038) were significantly associated with NSSI history in the final model.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that about 17% of participants reported a history of SA and 24% with NSSI. Both SA and NSSI were more common in girls and adolescents who had higher scores on depressive symptom severity scales. Maternal depression and youth history of NSSI were significant correlates of SA. Female sex, A-GBI depression scores, and history of SA were significantly associated with NSSI.

In this study, higher maternal BDI was associated with SA, not with NSSI. Previous longitudinal study reported that young adult offspring of depressed mothers are at higher suicidal risk than with non-depressed mothers [32]. Depressive symptoms of parents are known to relate to hostile and neglectful parenting [33]; in contrast, parental support appears to be a protective factor against the later development of suicidal behavior even in young adults [34]. Therefore, early detection and management of maternal depression could help reduce risk of SA in adolescents. However, with our study design, it is not certain whether maternal depression affect youth’s suicidality or is a results of youth’s suicidal attempt [13].

We found strong association between SA and NSSI in adolescents, consistent with prior work. SA and NSSI are known to share common risk factors such as low socioeconomic status, negative life events, family adversity, mood disorders and substance use disorders [3]. Several studies with adolescents reported that NSSI strongly predicted SA [35,36], and higher number of NSSI incidents predicted higher numbers of suicide attempts [37,38]. Other studies suggest a third variable linking NSSI and SA, rather than one being directly related [39]. However, NSSI and SA are frequently overlapping [11], consistent with present findings. In addition, most studies examining association between NSSI and SA were designed as cross-sectional [14]. It is not easy to make any conclusion about the directionality of the link between NSSI and SA [14,39]. In only a few longitudinal studies, baseline NSSI predicted of SA at 6 months follow-up, however, the reverse was not observed [40,41]. Those studies suggested that NSSI might be a stronger predictor of future SA than is SA a predictor of NSSI [40]. However, the causal relationship between NSSI and SA is not clear in present study design. Further prospective longitudinal study is needed to test any causal relationship between NSSI and SA.

In present findings, SA [42-45] and NSSI [46,47] both were more frequent in girls, again consistent with previous reports about adolescents. In 2019, the SA rate of Korean adolescents were reported 4.0% in females and 1.9% in males with national data [42]. The trend was similar in both population [42,45] or clinical samples [43,44]. Previous studies reported higher rates of NSSI and more cutting and scratching among female than male adolescents [46,47]. However, female sex was only associated with NSSI, not SA, in this study. The logistic regression model included sex and NSSI in the same blocks, so the shared covariance between them and SA was not awarded to either predictor. Further studies need to disentangle the relationship between SA, NSSI, and female sex.

Mood disorders such as depressive disorder and bipolar disorder were related with SA [48-51] and NSSI [52-54] in adolescents. SA [51] and NSSI [54] were known to be highly common and associate with more severe illness characteristics and mixed episode in youth with bipolar disorder. In addition, depressive disorder was the one of strongest predictors of future SA in previous studies [55,56]. In this study, higher A-GBI depressive scores were significantly associated with both SA and NSSI. However, higher score of CDI did not correlate with previous SA. CDI is thought to be limited in evaluating depressive symptoms during adolescence, a period characterized by mood fluctuation and irritability [57]. On the other hand, irritability and mood swings are known to be well evaluated by A-GBI [58]. The pattern of findings suggests that A-GBI could be more effective tool for detecting clinically significant and severe depressive disorder than CDI and other tools for adolescents. The “mixed” items on the A-GBI juxtapose depressive and hypomanic symptoms and rapid changes in mood and energy, and mixed states are well-established as a risk factor for self-harm [59].

There were several limitations to our analyses. First, this study was designed as a retrospective chart review. Thus, we relied on the electronic medical records for data. For the same reason, we could not administer structured interviews for the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. Third, we obtained data from a single institution, so caution would be warranted in generalizing present findings. This concern is mitigated to some degree by the consistency of present findings with prior published work. Fourth, data were cross-sectional, so the order of occurrence with these variables was not identified. Thus, we should be careful to interpret our findings as indicative of association, but not causality or sequencing. Lastly, we classified participants into three groups: Depressive disorder group, Bipolar disorder group, and Non-mood disorder group. The other psychiatric disorders than mood disorders were included into “Non-mood disorder group” only. Although functioning as a clinical control, the grouping heterogeneous disorders into one could have influenced the study results.

Our study suggests that NSSI and SA in adolescents are strongly associated with each other. Female sex and depressive symptoms of the adolescents were also significantly associated with NSSI in Korean adolescents. The patterns are consistent with findings in other countries, offering some hope that interventions addressing NSSI and SA may generalize as well.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2020R1A 5A8017671).

Notes

Dr. Kim received support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant number NRF-2020R1A5A8017671). Dr. Youngstrom has consulted with Pearson, Lundbeck, Janssen, Supernus, and Western Psychological Services about psychological assessment, received royalties from the American Psychological Association and Guilford Press, and is co-founder and president of Helping Give Away Psychological Science, a charitable organization recognized as a 501c3 charity by the Internal Revenue Service of the United States of America. Other authors have no potential competing financial interests to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyo-Won Kim, Han-Sung Lee, Kee Jeong Park. Data curation: Hyo-Won Kim, Han-Sung Lee, Kee Jeong Park. Formal analysis: Hyo-Won Kim, Han-Sung Lee, Kee Jeong Park. Funding acquisition: HyoWon Kim. Investigation: Yejin Kwon, Seung-Hyun Shon. Methodology: Hyo-Won Kim, Eric A. Youngstrom. Project administration: Hyo-Won Kim. Resources: Hyo-Won Kim. Software: Han-Sung Lee, Kee Jeong Park. Supervision: Hyo-Won Kim, Eric A. Youngstrom. Validation: Hyo-Won Kim, Eric A. Youngstrom. Visualization: Han-Sung Lee, Kee Jeong Park. Writing—original draft: Hyo-Won Kim, Han-Sung Lee, Kee Jeong Park. Writing—review & editing: Hyo-Won Kim, Eric A. Youngstrom.