The Effects of Inhumane Treatment in North Korean Detention Facilities on the Posttraumatic-Stress Disorder Symptoms of North Korean Refugees

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The study investigated the effects of severe human rights abuses in North Korean on Posttraumatic-stress disorder (PTSD) in North Korean Refugees (NKRs).

Methods

The study included 300 NKRs (245 females and 55 males) who completed self-report questionnaires that assessed PTSD, experiences of imprisonment, and exposure to inhumane treatment, by authorities in North Korea. A moderation analysis was conducted using a hierarchical multiple regression model to determine whether a moderation effect existed. In the next step, a post-hoc probing procedure of the moderation effect was performed using multiple regression models that included conditional moderator variables.

Results

The influence of the frequency of being imprisoned on PTSD varied as a function of recurrent exposure to inhumane treatment or punishment by authorities. Experiences of imprisonment were associated with PTSD only among those who were exposed to recurrent violence, such as beating or torture, by North Korean authorities.

Conclusion

The present findings highlight the significant effects of human rights violations, such as the inhumane treatment of prisoners in North Korea, on the PTSD of NKRs.

INTRODUCTION

Since 1998, more than 30,000 North Korean refugees (NKRs) have crossed into South Korea and each year there were approximately 1,000 more NKRs than the previous year. Most of the NKRs are women (72%) and most travel approximately 3,000 miles across China before resettling in South Korea. Even if they survive the ordeal of crossing China, they still face grave danger because the Chinese government continues to repatriate North Korean defectors to North Korea despite global concerns about the cruel treatment of defectors upon returning. If sent back, the refugees are at risk of extremely harsh punishments including torture, forced labor, forced abortions, and internment in prison-like facilities, such as labor training camps or holding centers. Most of these returnees are exposed to multiple traumatic events while at North Korean detention facilities. According to previous studies, more than 50% of NKRs have directly witnessed or been exposed to life-threatening events including experiencing starvation, witnessing public executions, and being sent to political prison camps [1]. Many studies of refugees have suggested that the traumatic events they endure are associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [2]. For example, the prevalence of PTSD among NKRs is reported to be as high as 52%. Furthermore, other studies have shown that particular types of trauma in populations with certain sociodemographic characteristics may lead to a greater risk of PTSD [3]. NKRs with more repatriation experiences have a higher likelihood of PTSD symptoms [4] and NKRs who experienced forced repatriation consistently exhibit a greater degree of overall mental health problems, including PTSD and paranoia.

Additionally, NKRs may have multiple experiences of human rights violations in North Korea, including arbitrary arrest, torture, inhumane treatment, and forced witnessing of public executions [5]. Studies investigating the mental health consequences of lifelong human rights abuses have reported increases in symptoms related to anxiety, depression, and PTSD and found that these symptoms might be significantly associated with exposure to brutal and inhumane treatment by authorities [6]. Although an increasing number of studies have examined the mental health consequences of traumatic events in NKRs, few studies have assessed how the experience of being detained in a detention facility in North Korea affects PTSD in NKRs or how human rights violations experienced in North Korea, such as severe violence in detention facilities, might be associated with mental health risk factors in NKRs [6].

Thus, the purpose of the present study was to assess relationships between imprisonment experiences and exposure to inhumane treatment in North Korean detention facilities and PTSD in NKRs who reached South Korea. The hypotheses were: 1) the frequency of imprisonment experiences in North Korea would be positively correlated with PTSD symptoms; and 2) the relationship between imprisonment experiences and PTSD would be moderated by exposure to inhumane treatment, such as beating and torture, inflicted by North Korean authorities. The results may deepen current insights into the mental health risk factors of NKRs and inform the administration of practical interventions for ameliorating PTSD through the development of individually tailored programs. The findings may also contribute to the establishment of policy alternatives regarding the improvement of mental health in NKRs by emphasizing their unique and stressful past experiences and preventing further human rights violations.

METHODS

Subject characteristics

This study was conducted from June–August 2017 and included 300 NKRs over 18 years of age who had resettled in South Korea. Because of the political stigma affecting the families they left behind, NKRs tend to conceal themselves and are difficult to locate. Of the approximately 30,000 NKRs in Korea, 300 were selected using the snowball sampling technique. Briefly, NKR recruiters introduced the researchers to several participants and these participants subsequently referred their acquaintances to the researchers. Recruitment took place through non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that serve NKRs by providing information about adaptation, psychological counseling, and medical consultation. Surveyors included three psychiatrists, three psychiatric residents, and two researchers who were trained for the survey; they met each subject, explained the purpose of the study, and received informed consent from each respondent. Participants then completed the questionnaire with assistance from surveyors. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Medical Center (IRB No.H-1704-077-002).

Measures

The survey consisted of questions that assessed sociodemographic factors (gender, age, education level in North Korea, and marital status), variables related to emigration [duration of stay (in years) in South Korea], variables related to imprisonment experiences, variables related to human rights violations (exposure to inhumane treatment by authorities, such as beating, torture, and exposure to human trafficking during the emigration process), and PTSD symptoms. The dependent variable was the score on the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), which was designed as a screening instrument to assess current PTSD symptoms related to past traumatic events. The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale that indicates how much the participant has been affected by past traumatic events. Preliminary validation work suggests a cutoff score of 38 for PTSD screening; the present study applied the same criteria. The primary independent variable was the experience of imprisonment. The participants were asked whether they had ever been imprisoned in detention facilities such as labor training centers, holding centers, and detention centers in North Korea. The response was coded as “yes” or “no”. The participants were asked whether they had ever been directly or indirectly (witnessed) exposed to human trafficking during the emigration process, to or violence such as beating or torture, by the authorities in North Korea. The responses were coded as “yes” or “no”

Statistical analyses

A descriptive analysis was performed to summarize the demographic variables, including the past traumatic events and PTSD symptoms of NKRs. The frequency and percentage for categorical variables and the mean and standard deviation (SD) for the numerical variables were reported. Two-sample t-tests or analyses of variance (ANOVA) were performed to compare differences in the mean PCL-5 score among the subcategories of the categorical variables, and a bivariate correlation analysis was performed to measure the linear correlation between the PCL-5 score and numeric variables. To evaluate the hypothesis that the effects of imprisonment experiences on PTSD were moderated by exposure to inhumane treatment (such as beating and torture) by North Korean authorities, a two-step modeling approach was employed. In the first step, the moderation analysis was conducted using a hierarchical multiple regression model to determine whether the moderating effect existed. Model 1 included the independent and moderating variables as main effects and the sociodemographic- and emigration-related variables as control variables while Model 2 included all Model 1 variables as well as an interaction term. In the second step, a post hoc probing procedure of the moderation effect was conducted using multiple regression models that included the conditional moderator variable [7]. The Huber-White robust sandwich variance estimation was applied in the regression model to account for heteroscedasticity. To ensure the absence of influential multicollinearity among the variables in the regression model, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was calculated. The threshold for statistical significance was set at 5% (two-tailed) and all statistical analysis was performed using Stata 16.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS

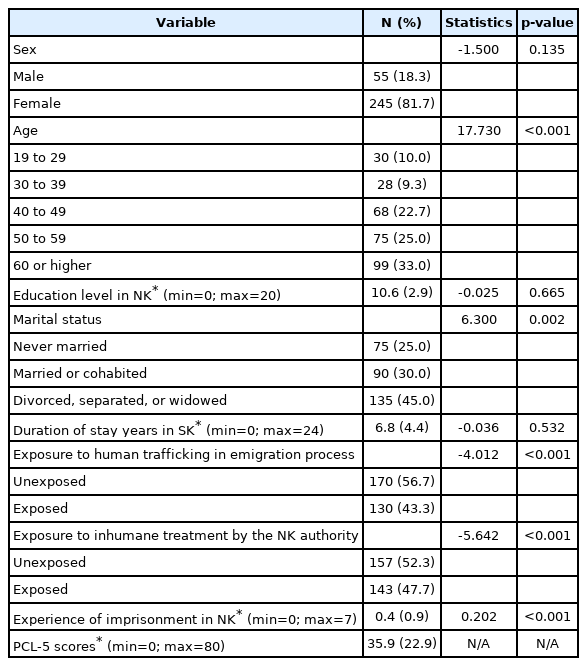

Table 1 lists the descriptive statistics of the demographic variables and traumatic experiences of the NKRs. Approximately half of the participants were 50 years of age or older (58.0%) and 81.7% of the participants were female. Of all the participants, 24.3% had been imprisoned in North Korea, 43.3% had been exposed to human trafficking during the emigration process, 47.7% had been exposed to battering, and 49.3% reported clinically meaningful PTSD symptoms (scores over the cut-off values). The PTSD symptoms differed significantly by age, marital status, exposure to human trafficking during emigration, and exposure to inhumane treatment in North Korean detention facilities (p<0.01). Additionally, the frequency of imprisonment experiences in North Korea was positively correlated with PTSD symptoms (p<0.001).

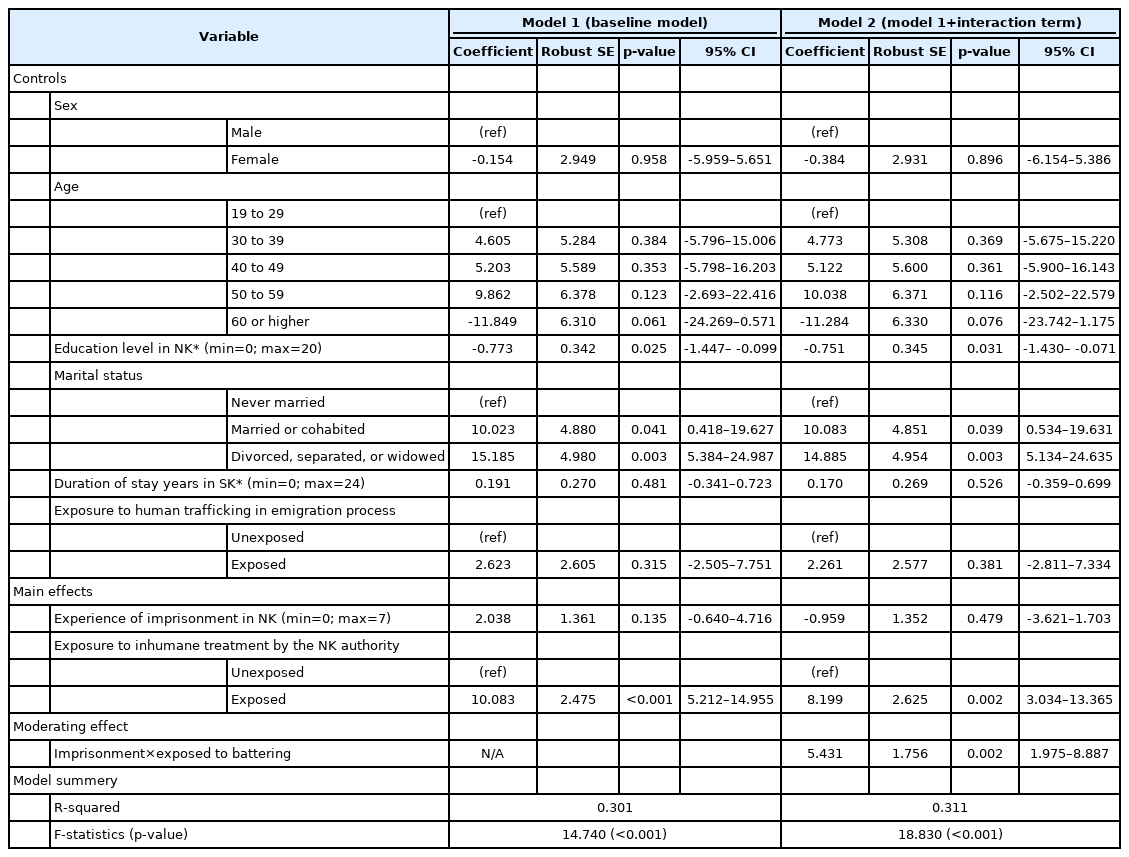

After controlling for sociodemographic- and emigration-related variables, the experiences of imprisonment, exposure to inhumane treatment in North Korean detention facilities, and the interaction of these variables were used to predict PTSD. The analysis revealed that the inclusion of the product term (coefficient=5.431; p=0.002) in the baseline model resulted in a significant increase in variance, accounted for by the predictor variables (ΔR2=0.010, p=0.004). This finding indicates that exposure to inhumane treatment, such as beating and torture, in North Korean detention facilities significantly moderated the relationship between the number of imprisonment experiences and PTSD (Table 2).

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis predicting PTSD (PCL-5) and interactive associations between frequency of experiences of imprisonment and exposure to inhumane treatment such as beating by the NK authority in North Korean Refugees

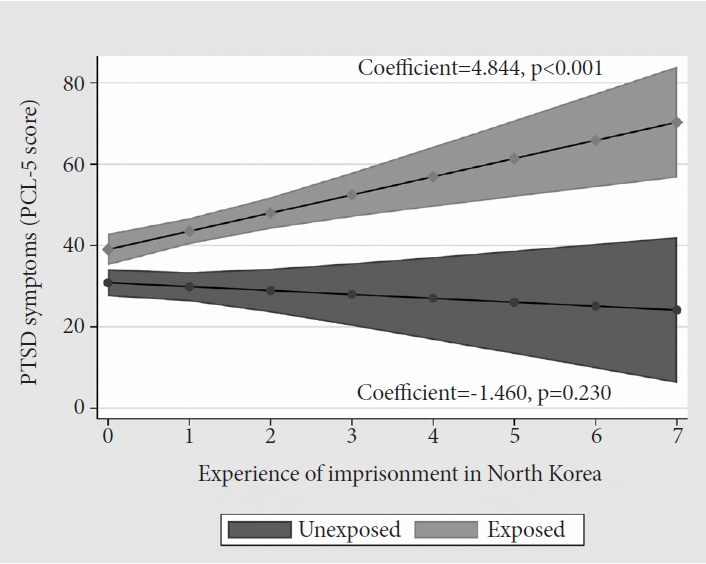

The post-hoc probing analysis revealed a moderating effect of exposure to inhumane treatment, such as beating and torture, in North Korean detention facilities such that there was a significant positive relationship between the frequency of imprisonment experiences and PTSD only in those NKRs with exposure to inhumane treatment in North Korean detention facilities (coefficient=4.844; p<0.001) (Table 3). The moderator effect is visualized as a simple slope comparison plot form in Figure 1.

Post-hoc probing regression analysis of moderating effect of exposure to inhumane treatment such as beating by the NK authority between frequency of experiences of imprisonment and PTSD

DISCUSSION

The present study found that the frequency of imprisonment experiences in North Korea was positively correlated with PTSD symptoms and that exposure to inhumane treatment, such as beating and torture, in North Korean detention facilities moderated this relationship. Of the 300 participants in this study, 24.3% had been imprisoned in North Korea and 47.7% had been directly or indirectly (witnessed) exposed to inhumane treatment, such as beating and torture, in North Korean detention facilities. These findings are similar to those of previous studies. For example, one study found that 49.3% of adult NKRs have either experienced or witnessed life-threatening events [8]. Similarly, a survey conducted at Hanawon, a government-sponsored educational facility for the resettlement of NKRs, revealed that the percentage of respondents who ‘were severely beaten in North Korea’ was 17.7–28.1% and that the percentage of respondents who ‘were sent to a corrective facility or a prison’ was 17.3–25.8% [2]. Other studies have reported that approximately 20% of NKRs have directly experienced extreme violence, such as torture [9].

The present study found that 49.3% of participants reported clinically meaningful PTSD symptoms. There are huge variations in the previously reported prevalence rates of PTSD, which range from 4–52% [1]. It is possible that the prevalence of PTSD was higher in the present study due to the use of a self-administered scale to assess PTSD symptoms, rather than the clinical criteria used in previous studies to diagnose PTSD, Additionally, different studies may have included different diagnostic methods and criteria, various age ranges of participants, and various sampling methods; this could partially explain the heterogeneity of results seen in refugee studies. Nevertheless, a case-control study found that NKRs have a higher than average level of PTSD symptoms when compared to the general South Korean population. The prevalence rates of anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms among NKRs are notably higher than the rates of anxiety (6.8%), depression (3.1%), and PTSD (0.6%) in South Koreans. However, they are similar or even higher than the symptoms reported by those involved in major complex humanitarian emergencies such as natural disasters or conflicts [10,11].

The traumatic experiences of NKRs in North Korea could be a mental health risk factor that hinders their successful resettlement in South Korea. Therefore, it will be necessary to develop individually tailored programs to improve PTSD in NKRs, given that their traumatic experiences negatively affect life satisfaction, especially economic satisfaction, in South Korea. Furthermore, neuropsychological studies have consistently identified impairments in declarative memory and verbal memory in patients with PTSD [12,13], and NKRs may have attention deficits that could be related to their psychiatric symptoms, particularly dissociation [14]. In the present study, analyses of the relationships between trauma exposure and comorbid mental health problems as well as the mediation effects of PTSD on trauma and mental health variables revealed that interpersonal trauma significantly contributed to comorbid mental health problems through PTSD [15]. Because the negative effects of trauma were primarily mediated by psychiatric symptoms, strategies aimed at relieving the psychiatric symptoms of traumatized refugees may aid with their successful adaptation into South Korea.

This study had several limitations that should be noted. First, the study findings are based on retrospective data from an NKR population who were recruited by snowball sampling and may not be generalizable to the entire NKR population. For example, the crude sex ratio distribution was 81.67% (female) to 18.33% (male), so more women than men were included in this study relative to the estimated population of resettled NKRs since 1999 (72% women and 28% men) [16]. Second, the mental health instrument used in the present study, the PCL-5, has not been specifically validated in the context of NKRs in South Korea. However, this scale has been validated in various other countries and the Korean version of the PTSD Checklist-civilian version (PCL-C), which was developed based on the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD, is a reliable and valid measure of PTSD symptoms among NKRs [17]. Third, we could not perform qualitative analyses because we used quantitative self-reported questionnaires to assess the traumatic experiences and mental status of the NKRs. Future studies using indepth interviews would provide further insights into the relationship between exposure to inhumane treatment in North Korea and PTSD in NKRs.

The present study is the first to report the moderating effect of human rights violations on the relationship between imprisonment in North Korea and PTSD in NKRs in South Korea. More rigorous studies will be needed to investigate the longterm interactions between PTSD in NKRs and their pre- and post-migration experiences as well as their personal characteristics. More work is required to develop and implement psychiatric interventions targeting this specific population through adequate policies. The findings of the present study suggest that collaborative social work between mental health care communities and human rights activists could be useful in assisting the successful resettlement of NKRs with PTSD symptoms in South Korea. Additionally, the findings suggest the need for enhanced awareness about human rights issues in North Korea.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Mental Health R&D Project, funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HL19C0007).

Notes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authors’ contribution

Conceptualization: So Hee Lee, Won Woong Lee. Data curation: So Hee Lee, Haewoo Lee, Jin Yong Jun. Formal analysis: Jin-Won Noh, Kyoung-Beom Kim. Funding acquisition: So Hee Lee. Investigation: So Hee Lee, Hae-Woo Lee, Jin Yong Jun. Writing—original draft: So Hee Lee, Jin-Won Noh. Writing—review & editing: Won Woong Lee.