Design and Methodology for the Korean Observational and Escitalopram Treatment Studies of Depression in Acute Coronary Syndrome: K-DEPACS and EsDEPACS

Article information

Abstract

Depression is common after acute coronary syndrome (ACS), adversely affecting cardiac course and prognosis. There have been only a few evidence-based treatment options for depression in ACS. Accordingly, we planned the Korean Depression in ACS (K-DEPACS) study, which investigated depressive disorders in patients with ACS using a naturalistic prospective design, and the Escitalopram for DEPACS (EsDEPACS) trial, which assessed the efficacy and safety of escitalopram for treating major or minor depression in patients with ACS. Participants in the K-DEPACS study were consecutively recruited from patients with ACS who were recently hospitalized at Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, South Korea. Diagnoses were confirmed by coronary angiography from 2005. Data on depressive and cardiovascular characteristics were obtained at 2 weeks, 3 months, 12 months, and every 6 months thereafter following the index ACS admission. The K-DEPACS participants who met the DSM-IV criteria for major or minor depressive disorder were randomly assigned to groups in the 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled EsDEPACS trial beginning in 2007. The outcome of treatments for depressive and other psychiatric symptoms, issues related to safety, including general adversity, and cardiovascular factors were assessed. The K-DEPACS study can significantly contribute to research on the complex relationships between depression and ACS. The results of the EsDEPACS trial provide an additional treatment option for clinicians treating these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Relationships between depression and acute coronary syndrome

Depression is common in acute coronary syndrome [ACS; including myocardial infarction (MI) or unstable angina (UA)]. The prevalence of major depression was estimated to range from 15% to 27%.1 Furthermore, the occurrence of depressive symptoms after ACS has been associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates. Major depression was found to be the greatest predictor of the cardiac prognosis of patients with ACS, accounting for more than a twofold risk of developing an adverse cardiac complication.2

Pharmacological trials for depression in ACS

A number of randomized controlled trials, mostly with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have examined the impact of pharmacological interventions on depression in patients with ACS. However, the trials conducted addressing this theory have produced mixed results. Fluoxetine was shown to be effective and safe for treating patients with post-MI depression.3 However, the limitations of this study were the small sample (n=54) and short treatment period (9 weeks) used to draw a conclusion. The Sertraline Antidepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) involved 369 patients with major depression who were hospitalized with ACS and randomly assigned to receive sertraline or placebo for 24 weeks.4 Sertraline was found to be safe in these patients, but the overall efficacy results were less convincing. There was a restricted benefit of sertraline over placebo for the subgroup of patients with recurrent depression and those with a more severe depression. Mirtazapine was studied as a part of larger Myocardial Infarction and Depression-Intervention Trial (MIND-IT) that used a 24-week placebo-controlled design with 91 patients with major and minor depression post-MI.5 Although mirtazapine was shown to be safe and effective for achieving secondary outcomes, the results were complicated by a negative finding about the primary outcome and the small number of patients completing the study trial (n=40). Citalopram was found to be safe and superior to placebo in reducing depressive symptoms in a 12-week Canadian Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy (CREATE) trial.6 However, the outcome of this study was drawn from a different population of patients with moderate-to-severe depression at late stage after hospitalization (ranging from 3 weeks to 31 years) for cardiac reasons.

Limitations of the previous studies

First, previous clinical trials have focused primarily on major depressive disorders.7 However, minor depressive disorders are even more common than major depressive disorders in patients with ACS,1,8 and these have negative effects on cardiac prognosis.9,10 Therefore, clinical trials are needed to evaluate the effect of minor depressive disorders in ACS. Second, previous randomized controlled trials have reported that serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) were safe, but their antidepressant effects on patients with ACS were inconclusive because of small samples, low completion rates, controversial results, or heterogeneous study populations. Clinicians need more effective treatment options for these patients.

The K-DEPACS and EsDEPACS studies

We designed the Korean Depression in Acute Coronary Syndrome (K-DEPACS) to complement previous studies. The present study investigated depressive disorders in patients with ACS using a naturalistic prospective design. Patients with a diagnosis of a major or minor depressive disorder were enrolled in a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy and safety of Escitalopram for Depression in ACS (EsDEPACS). The trial is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov, registry number: NCT00419471. Escitalopram was chosen because of its antiplatelet effects in depressed patients,11 and it was safe and well tolerated in clinically non-depressed patients with a recent ACS diagnosis who were treated for 1 year.12 However, whether this drug is effective for treating depression with ACS remains unproven. Both K-DEPACS and EsDEPACS are investigator-initiated and designed studies.

The K-DEPACS study investigated the occurrence, risk factors, and longitudinal course of psychological disorders (depression in particular) in survivors of recently developed ACS as well as the effects of depression on cardiac course and prognosis. The EsDEPACS study evaluated the efficacy and safety of escitalopram in the treatment of depressed patients with ACS and determined the effects of escitalopram on other psychiatric outcomes, including social functioning, disability, and quality of life.

METHODS

Study outline and recruitment

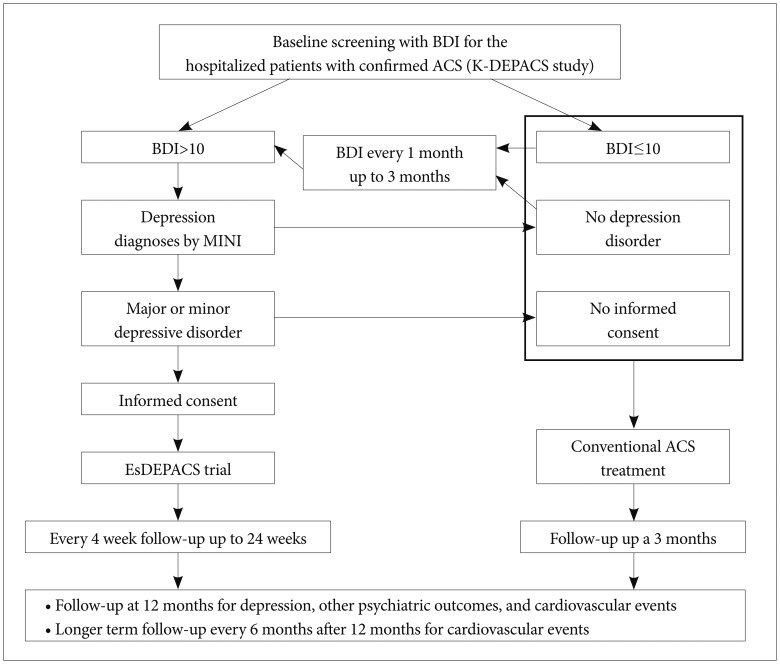

The outlines of the K-DEPACS and EsDEPACS studies are presented in Figure 1. The K-DEPACS study investigated the epidemiology of depressive disorders in patients with ACS using a naturalistic prospective design and has been supported by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare since 2005. Participants were consecutively recruited from patients recently hospitalized with ACS; diagnosis was confirmed by coronary angiography and laboratory examinations performed at the Department of Cardiology of Chonnam National University Hospital, Gwangju, Korea. Among patients who met eligibility criteria and agreed to participate, psychiatric assessments were made at 2 weeks, 3 months, 12 months, and every 6 months thereafter following ACS diagnosis to investigate consequences of ACS at acute, subacute, and chronic stages. Potential participants in the EsDEPACS study were screened for depressive symptoms with the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)13 during hospitalization at 2 weeks after ACS diagnosis and, at an outpatient clinic, every 1 month thereafter up to 3 months. Patients with depressive symptoms (BDI >10) were clinically evaluated by the study psychiatrists using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview using DSM-IV criteria to diagnose major or minor depressive disorder.14 Beginning in 2007, patients with a diagnosis of major or minor depressive disorder who agreed to participate were randomly assigned to the EsDEPACS study, which was, supported by H. Lundbeck A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark). Patients who were not depressed or who were depressed but did not want to participate in the EsDEPACS study received conventional treatment for ACS and were evaluated with the K-DEPACS protocol.

Study subjects

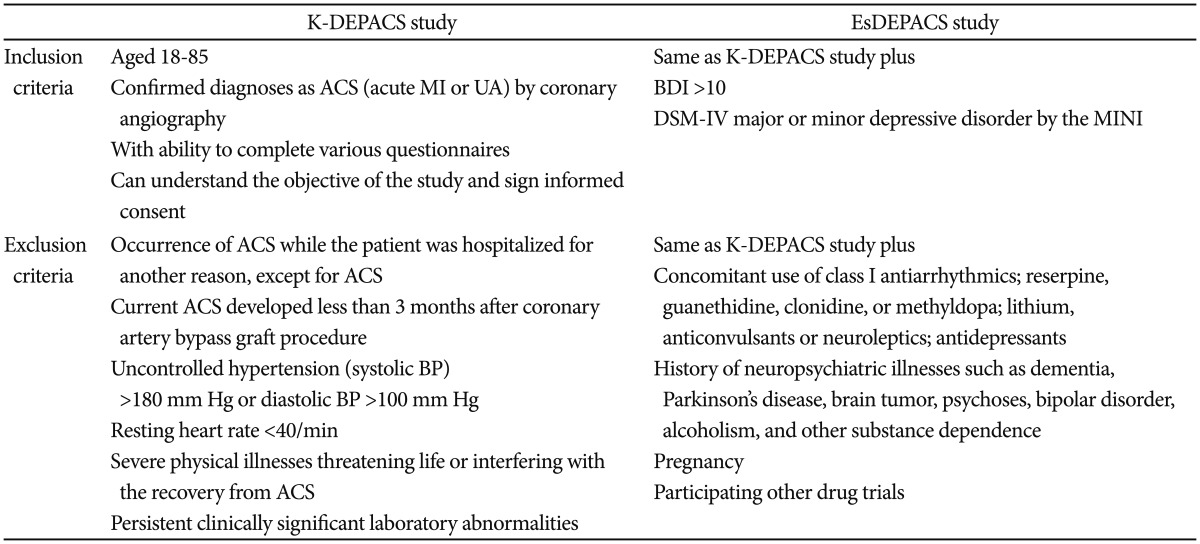

All patients who visited the study site with angina symptoms and were hospitalized were approached for enrollment in the K-DEPACS study at 2 week after the index ACS. Patients who met the depression criteria in that hospitalized setting or at an outpatient setting, every 1 month thereafter up to 3 months were qualified for inclusion in the EsDEPACS study. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for both studies are summarized in Table 1.

Assessment and measurements for the K-DEPACS study

General information on socio-demographic characteristics and health status were obtained. Cardiovascular medications were recorded. Measurements of depressive symptoms included the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD),15 the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),16 the BDI, and the Clinical Global Impression Scale-severity (CGI-s).17 We used four scales because they differed from one another in several ways: the HAMD is the observer-rated scale most widely used in research on depression related to ACS18; the MADRS (another observer-rated scale) does not include items for evaluating the somatic symptoms of depression, which may be difficult to differentiate from the physical consequences of ACS; the BDI is a self-report measure; and the CGI-s assesses global symptomatology and can be used quickly in a busy clinical setting. Scales used to assess other psychiatric symptoms included the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS),19 the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule-12 (WHODAS-12),20 and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale-abbreviated form (WHOQOL-BREF).21 We included these measures given recent recommendations that depression outcome research involve multifaceted evaluation (i.e., more than only the HAMD) to address psychological wellbeing and functioning.22 Additionally, personality was assessed at the 3-month evaluation point using the Big Five Inventory (BFI).23 All assessment scales had been formally translated and standardized in Korean.24-30 Cardiac risk factors included self-reported diagnoses of and treatment histories for hypertension and diabetes mellitus; resting blood pressure (BP); fasting cholesterol levels; body mass index; and current smoking status. Coronary angiography results were used for diagnoses of MI or UA. Echocardiography results included left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and wall motion scores. Electrocardiography (ECG) variables were heart rate (beats/min), PR interval (ms), QRS duration (ms), and QTc duration (ms). Laboratory tests for serum cardiac biomarkers troponin I and creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB) were measured. New cardiovascular events, including angina, heart failure, or death, were recorded.

The EsDEPACS trial

Randomization and intervention

The efficacy and safety of flexible doses of escitalopram (5 mg, 10 mg, 15 mg, or 20 mg) were investigated using a double-blind, placebo-controlled design. The escitalopram and placebo were provided by H. Lundbeck A/S (Copenhagen, Denmark). Patients were randomized in a 1 : 1 ratio for assignment into the ecsitalopram or placebo group according to computer-generated randomization codes. Patient visits were scheduled at baseline and at 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 24 weeks (±7-day visit window was allowed) thereafter. Patients received one tablet of escitalopram 5 mg, 10 mg, or 20 mg or two tablets of escitalopram (5 mg plus 10 mg) for a 15-mg dose per day or a matched placebo. The initial dose at baseline evaluation was typically 10 mg/day, but subjects aged 65 years or over and those with hepatic dysfunction received 5 mg/day. After the second evaluation (week 4), the medication doses could be changed and were determined by the investigators' clinical judgment based on the response to and tolerability of treatment. Medications were taken orally once daily within 30 min after supper. Adherence to the medication regimen was confirmed by pill counts at every visit and was defined as acceptable when at least 75% of the medication was taken. At the end of 24 weeks of double-blind treatment, the study was completed, and study medication was tapered. To ensure patient safety, follow-up treatment was provided at the outpatient clinic of the psychiatric department when the clinician determined a need for further treatment. Concomitant medications, such as any other antidepressants, psychostimulants, antipsychotics, and anticholinergics, were not permitted. However, transient use of analgesics, antipyretics, and cold medicines, as well as hypnotics such as zolpidem, triazolam, and benzodiazepines, was allowed.

Outcome measures

The primary efficacy outcome measure was the HAMD. The secondary depression outcome measures were the MADRS, BDI, and CGI-s. Other psychiatric outcome measures included the SOFAS, WHODAS-12, WHOQOL-BREF, and Chonnam National University Hospital-Leeds Sleep Evaluation Questionnaire (CNUH-LSEQ).31 The HAMD, MADRS, BDI, CGI-s, and CNUH-LSEQ were administered at baseline and every follow-up visit; the SOFAS, WHODAS-12, and WHOQOL-BREF were assessed at baseline and at follow-up weeks 4, 12, and 24. The BFI was administered at follow-up week 12. In terms of general safety outcomes, adverse events during the study period were recorded at all visits. Serious clinical and laboratory adverse events were assessed. Discontinuation of participation in the study due to adverse events was recorded. In terms of cardiovascular safety outcomes, results on echocardiography (LVEF and wall motion), ECG (heart rate, PR interval, QRS duration, and QTc duration), laboratory tests (troponin I, CK-MB, and total cholesterol), and body weight were measured at baseline and at last follow-up visit. Resting BP was measured at baseline and every follow-up visit. After finishing the EsDEPACS trial, all participants, regardless of completion status, were approached regarding participation in the K-DEPACS long-term follow-up evaluations scheduled at 12 months and every 6 months thereafter (Figure 1).

Sample size

The overall sample size was estimated from the number of subjects needed for the EsDEPACS trial. The ESDEPACS trial was designed to produce 80% power to detect small to medium effect sizes (0.35) on the primary efficacy outcome for both treatments (i.e., a mean score difference of 2 on the HAMD assuming a SD of 5-6) in the ITT analyses for all randomized participants when performing two-sided tests at α=0.05. These assumptions yielded a sample size of 106 patients per group. As a previous study reported that a considerable proportion of Korean patients who were depressed (30%) discontinued the study after the baseline evaluation,32 we decided to enroll a total of 300 patients with ACS who were also depressed (150 subjects per group) for the EsDEPACS trial. We predicted that two-thirds of these patients would participate in the EsDEPACS study and that one-third may not want to participate. Therefore, approximately 450 depressed patients were needed for the EsDEPACS study. The prevalence of major depression reportedly ranges from 15% to 27% (approximately 20%), and at least a comparable proportion of patients with ACS have minor depression.1 Based on these estimates, we predicted that 40% of the sample would meet criteria for major or minor depressive disorders. Accordingly, approximately 1125 patients with ACS were needed to provide a pool of 450 depressed patients and to enroll 300 in the EsDEP

CONCLUSION

The K-DEPACS study is a meaningful and significant contribution to the research on the complex relationships between depression and ACS. The particular prospective naturalistic study design might facilitate other related studies and enhance the understanding on this issue.33 The EsDEPACS trial is the first to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of escitalopram for treating depression in ACS patients. Despite the high prevalence and negative effects of depression in ACS patients, only a few evidence-based options are currently available for the treatment of depression in these patients. We believe that the results of the EsDEPACS trial provide an additional treatment choice for clinicians who treat these patients.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health 21 R&D, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HI10C2020) and an unrestricted research grant from H. Lundbeck A/S. The funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.