Decreased Health-Seeking Behaviors in People With Depressive Symptoms: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2014, 2016, and 2018

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of depressive symptoms on health-seeking behaviors using the large epidemiological study data of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination (KNHANES).

Methods

Data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), which is a large-scale national survey, were used in this study. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to assess the depressive state of the participants. Specialized self-reported questionnaires that included questions about health-seeking behaviors were also performed. To examine the relationships between depression and health-seeking behaviors, complex sample logistic regression models with control for covariates were used.

Results

There was a significant association between decreased health-seeking behaviors and depressive symptoms in adults (odds ratio [OR]: 3.11, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.44–3.96). The association was found to be especially strong in males (OR: 2.63, 95% CI: 1.69–4.10) versus in females (OR: 2.49, 95% CI: 1.90–3.27). With regard to age group, younger adults (19–44 years of age) showed the highest OR (OR: 3.07, 95% CI: 2.12–4.45).

Conclusion

Our findings support the idea that there is a significant association between health-seeking behaviors and depressive symptoms in the Korean population. These results suggest that individuals with decreased health-seeking behaviors could be evaluated for depressive symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

Health-seeking behaviors refer to acts during which an individual makes decisions and/or takes direct action to ensure or promote a healthy life or prevent or address disease [1]. Demonstrating proper health-seeking behaviors is especially important for patients with illnesses because, if diagnosis of acute disease is delayed due to not visiting the medical facility at the appropriate time, it might adversely affect the course of the disease [2-5]. Chronic diseases such as hypertension, cerebrovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and asthma are specifically known to cause problems throughout the course of the disease if proper health-seeking behaviors are not undertaken [6-8]. Additionally, the existence of these health-seeking behaviors is very important for management of complications that may occur after surgery [9].

The variables reported to affect health-seeking behaviors include environmental factors (e.g., the health care system, the distance between the medical facility and the patient’s residence, the patient’s physical ability to visit medical facilities) [10,11]; socio-economic factors (e.g., patient insurance status, level of household income, level of education, family structure) [11-13]; and cultural factors [14,15].

It is also important to demonstrate proper health-seeking behaviors in the case of depression because visiting the clinic at the appropriate time could help prevent a suicide attempt [16,17]. Depression may also influence health-seeking behaviors [18-21]; however, the results to indicate a definitive connection are still controversial. Ramirez-Avila et al. [22] found that depressed patients with HIV were less likely to visit the hospital and to not participate in follow-up screening tests. Bunde and Martin [23] also concluded that depression in patients with myocardial infarction might aggravate the course of disease by decreasing the health-seeking behaviors of these patients. In addition, other researchers found a correlation between fewer dental check-ups and depression in the elderly [24]. In a study of stroke patients, it was reported that depressive symptoms decreased health-seeking behaviors [25]. In contrast to these, however, Nagai [20] found that depression increased actual health-seeking behaviors, even though it decreased the severity of health-seeking intention.

Despite these investigations, there have been no studies conducted on the effects of depression on health-seeking behaviors based on large-scale demographic data. Thus, the purpose of this current study was to investigate the effects of depression on health-seeking behaviors using the large epidemiological study data of the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES).

METHODS

Study participants

This study analysed the data from the sixth KNHANES (2014, 2016) and seventh KNHANES (2018). The KNHANES is a large-scale national survey conducted for the purposes of comprehensively understanding the health and food consumption status of the Korean population, developing health policies for South Korea, and informing plans for the improvement of quality of life. This survey was performed with the approval of the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Disease Control Division (IRB No. 2013-12EXP-03-5C and 2018-01-03-P-A).

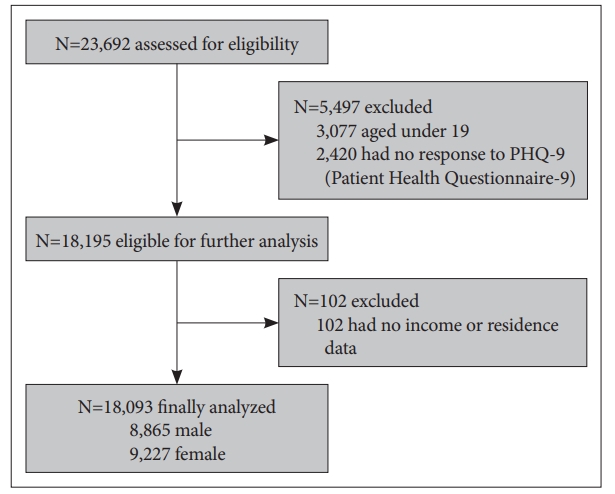

Among the 23,692 participants who enrolled in the KNHANES, 18,093 participated in the survey. Participants who were aged 19 years and older were invited to participate in a health interview that included the administration of a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); in total, participants meeting the age criterion completed the interview. During the survey, PHQ-9 was conducted once every two years, so data were collected on a two-year basis. Figure 1 shows the detailed selection criteria for the participants.

Research data

The KNHANES was performed by stratified, clustered, and systematic sampling, not by simple randomization. Two-level hierarchical clustering was used in KNHANES. Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) were extracted from 303,180 geographically defined PSUs to represent 192 basic administrative areas and housing types in the first phase. Each PSU included an average of 60 households; from each PSU, 20 households were extracted by applying systematic sampling system with intra-stratification of residential area, age, and gender [26]. In addition, for understanding the health and nutrition status of the total population across the whole nation, the sample of KNHANES was weighted to represent the entire Korean population. Therefore, statistical methods should be selected in consideration of the weighted sample.

KNHANES was divided broadly into a health interview, screening tests, and nutrition survey. The nutrition survey was conducted using standardized and validated questionnaires. In order to understand the basic characteristics of the subjects, we used the answers to the items about gender, age, education level, residence area, household income level, number of family members, and medical illness.

The answer to the question of whether the subject had decreased health-seeking behaviors or not was determined according to their response to the item, “Have you ever been unable to go to the clinic (except for dentistry) during the previous year?,” which was included in the health questionnaire. Those individuals who answered “yes” to this item were thought to be displaying decreased use of the medical facilities and were classified as those with decreased health-seeking behaviors. On the other hand, those who answered “no” were regarded to be those without decreased health-seeking behaviors.

In order to investigate whether participants had limitations of mobility, we used the Euro Quality of life-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) questionnaire, a tool developed in Europe that is used for examining the quality of life of an individual [27]. The EQ-5D consists of five items, including questions about mobility. Participants who responded affirmatively to the item “I am comfortable with walking” were classified as those without a limitation of mobility, while those who responded affirmatively to “I have some difficulty walking” and “I want to be lying down all day” were categorized as limitation of mobility.

To assess the presence of depression in the participants, we used the self-administered questionnaire, PHQ-9. This questionnaire is a valid screening tool for depression and also can be used to examine the severity of depression. We defined depression when the PHQ-9 total score was 5 or more, in accordance with the validation study of PHQ-9 conducted on a sample of the Korean population [28].

In addition, participants were classified into three groups based on age: specifically, those aged 19 years to 44 years, those aged 45 years to 64 years, and those aged 65 years or older. Residence area was divided into urban and rural, while the degree of education was divided into four stages: elementary school graduation, junior high school graduation, high school graduation, and university graduation. Household income level was calculated as the square root of monthly household income/number of household members. We designated participants who responded “yes” to the inquiry “I was diagnosed by a doctor” as the medical disease-affected group.

Analysis

Since the data from KNHANES were collected using stratified, clustered, and systematic sampling, analysis methods for complex samples were used while following the guidelines of KNHANES analysis, which were published by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [29].

To identify the characteristics of the participants and the entire Korean population, complex sample frequency analysis was used. We also used complex sample crosstab analysis with the chi-square test to determine the difference between depressed and normal controls except the comparison for age, which we compared using an unpaired t-test. A complex sample logistic regression model was used to examine the relationship between depression and health-seeking behaviors. Gender and age, which would affect the association between depression and health-seeking behaviors were adjusted for in this analysis. The independent variables also included environmental factors such as residence area and limitation of activity; socioeconomic factors such as household income level, type of family structure (whether he/she lives alone), and education level; and medical illnesses such as arthritis, asthma, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, pulmonary tuberculosis, and thyroid disease. Among the young participants aged between 19 and 44 years, only nine individuals had cerebrovascular disease and coronary artery disease. As such, the number of patients was too small to adjust for these two diseases at this age range, so we excluded these two illnesses from covariates in the analysis for the youngest group.

For the analysis of the frequency of complex sample crossover analysis and complex sample logistic regression analysis, the planning variables were the Kstrata as a stratification variable, the PSU as a cluster variable, and weight (Wt_itvex). The collected data were analysed using Stata MP 16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) program. In order to understand the general characteristics of the group, we used complex sample frequency analysis.

RESULTS

General characteristics of the subjects

Among participants of the KNHANES, were selected for inclusion in the present study after excluding persons aged less than 19 years and persons who did not respond to the PHQ-9 questionnaire. The final adults comprised men and women (Figure 1).

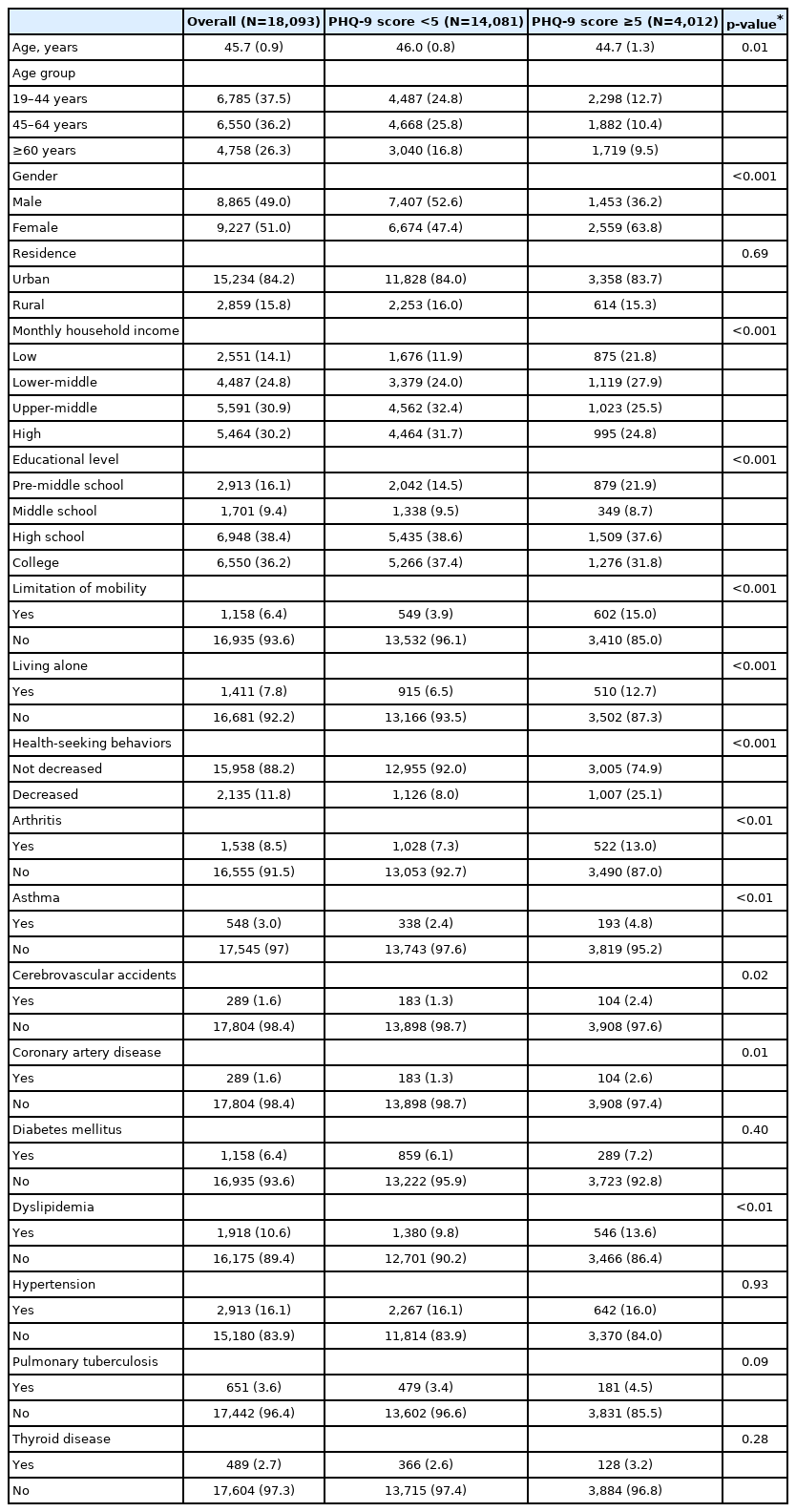

Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the subjects. Their mean age was 45.7 (44.8–46.6) years: 46.0 (45.2–46.9) years in the control group and 44.7 (43.2–46.2) years in the depressed group. Fifty-one percent of the subjects were female, and the proportion of women in the control group was 47.4% versus 63.8% in the depressed group. Among all of the subjects, 11.8% displayed decreased health-seeking behaviors; 8.0% (1,126 persons) in the control group and 25.1% (1,007 persons) in the depressed group.

Furthermore, there were significant differences in the control group and the depressed group in terms of age, gender, monthly household income, educational level, limitation of mobility, living alone, and decreased health-seeking behaviors (p<0.01 for all). Differences were also found with respect to incidence of arthritis (p<0.01), asthma (p<0.01), cardiovascular accidents (p=0.02), coronary artery disease (p=0.01), and dyslipidemia (p<0.01).

Association between depressive symptoms and health-seeking behaviors

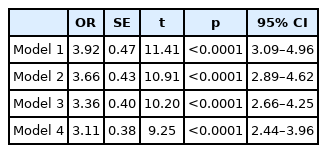

Table 2 shows the relationship between depressive symptoms and decreased health-seeking behaviors by complex sample logistic regression analysis. The analysis was conducted in the following order: 1) unadjusted; 2) adjusted for age and gender; 3) adjusted for age and gender as well as residence, monthly household income level, education level, limitation of mobility, type of family structure (i.e., whether he/she lives alone); and 4) the aforementioned items and the presence of any of nine medical illnesses comprising arthritis, asthma, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, pulmonary tuberculosis, and thyroid disease.

In Model 1, which was unadjusted, the probability of depressed people having decreased health-seeking behaviors was significantly higher than in the control group (odds ratio [OR]: 3.92; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.09–4.96). Model 2 also showed the same tendency (OR: 3.66; 95% CI: 2.89–4.62). In Model 3, which was controlled for socio-economic factors of monthly household income level, education level, and type of family structure as well as environmental factors of residence and limitation of mobility, the results were consistent (OR: 3.36; 95% CI: 2.66–4.25). Finally, Model 4, which was adjusted for all independent variables (i.e., age, gender, residence, monthly household income level, education level, limitation of mobility, type of family structure, and presence of any of nine medical illnesses) showed an OR of 3.11 (95% CI: 2.44–3.96), which was consistent with the other results.

Comparison by gender and agegroup

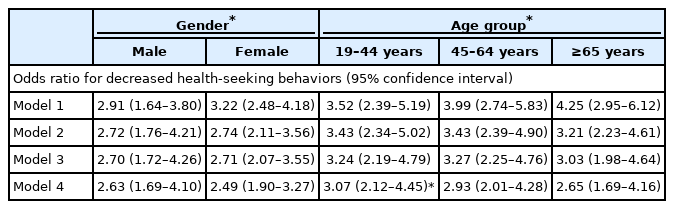

Table 3 shows the results after adjusting for all independent variables according to gender and age, respectively. The results of the analysis by gender showed that both males and females were significantly more likely to demonstrate decreased health-seeking behaviors in the depression group (Table 3). In addition, when all independent variables were controlled (Model 4), the OR was 2.63 for males and 2.49 for females; that is, health-seeking behaviors were more highly reduced in conjunction with depression in men than in women.

Adjusted associations between decreased health-seeking behaviors and depressive symptoms by gender and agegroup

As part of this study, the study subjects were divided into three groups according to age; 19 years to 44 years, 45 years to 64 years, and 65 years or older. After that, all independent variables were controlled (Model 4), and the results indicated that all three age groups were significantly more likely to have decreased health-seeking behaviors when depressed.

The OR was 3.07 for the youngest group and 2.93 and 2.65 for the middle-aged group and the elderly group, respectively. It was suggested that depressive symptoms were most likely to be associated with decreased health-seeking behaviors in the youngest group and least associated in the old-aged group.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of depressive symptoms on health-seeking behaviors using the large epidemiologic data of the KNHANES. We aimed to clarify whether depressive symptoms could affect health-seeking behaviors as well as environmental factors, socioeconomic factors, and cultural factors, which are previously known to have effects on health-seeking behaviors in patients who have medical illnesses [1]. We also aimed to examine the effects of depressive symptoms on the health-seeking behaviors of patients as well as the effects on the progression and prognosis of illnesses affecting the patients.

According to the results of this study, people with a PHQ-9 total score of 5 or higher were more likely to display decreased health-seeking behaviors. That is, there was a high possibility that people with depressive symptoms were not as likely to visit the clinic for one year. The same tendency was observed when controlling for socioeconomic and environmental factors, as well as gender and age. That is, depressive symptoms would still negatively impact health-seeking behaviors even if adjusting for environmental factors, socioeconomic factors, and medical illnesses as covariates.

Depression is characterized by the following symptoms: psychomotor retardation and fatigue, loss of volition, and loss of interest. Therefore, people with depressive symptoms may neglect to take care of themselves, visit the hospital, or receive appropriate treatment when needed [22,24]. It is also known that depression causes cognitive distortion and negative problem orientation, which can affect patients’ awareness of their medical problems and their demonstration of health-seeking behaviors [30-32].

When we examined the relationship between decreased health-seeking behaviors and depression by gender, it was found that males were more likely to have decreased health-seeking behaviors than females.

Males and females differ in their symptoms and coping styles when they have depression; for example, males are more likely to be impulsive and show risk-taking behaviors like alcohol and drug use when they are depressed [33]. In the Confucian culture of Korea, which values masculinity, depressed males are also less likely to seek help or to visit doctors than females because they may think that it is not masculine [34,35]. Depressed females, in contrast, tend to be more agitated than males and to avoid problems [33]. In other words, when a woman is aware of her health problems, she tries to solve them more actively. These gender differences in depressive symptoms and coping strategies could help explain the results of this study, which showed that males with depressive symptoms were more likely to show decreased health-seeking behaviors than females.

We also examined the relationship between depression and health-seeking behaviors by dividing the study cohort into three groups according to age. In this study, it was less likely that the middle-aged group (aged 45–64 years) would show decreased health-seeking behaviors in comparison with the younger age groups (aged 19–44 years) when they were depressed. It was also found that the youngest group (aged 19–44 years) would be more likely to have decreased health-seeking behaviors than the other age groups when they have depression. It is known that middle-aged people have less somatic symptoms than other age groups such as adolescents and early adults [36].

Previous study has also shown that younger individuals with depression mainly suffer from cognitive distortion and negative problem orientation [32]. Therefore, the middle-aged group would show weaker associations with decreased health-seeking behaviors and depression versus the youngest age groups. In other words, even when there is depression in middle-aged groups, the behavior of visiting hospitals when recognizing pain is higher than that of other subgroups. However, the youngest group could be hypothesized to be more likely to have distorted cognition about their health status and to demonstrate decreased health-seeking behaviors; that is, the youngest group would be more likely to not visit doctors despite their needs versus older groups.

In addition, in contrast to the trend of a decrease in OR with an increase in the number of adjusted covariates observed in other age groups, the OR was found to be increased in the elderly when medical illnesses were controlled, as compared with when they were not controlled. This could be explained by the characteristics of the elderly, as they are more likely to have medical problems than other age groups [37]. The elderly are more likely to visit the hospital due to their medical conditions and thus have a lower possibility of having decreased health-seeking behaviors [38]. Also, it is known that when patients are depressed, older age groups complain of more anxiety and hypochondriasis [39]. Therefore, it seemed that decreased health seeking behaviors were less strongly associated with depressive symptoms when the presence of medical illness.

If the patient demonstrates decreased health-seeking behaviors despite the need for medical attention, environmental factors, socio-economic factors, and cultural factors are often considered. However, according to our study, it is also necessary to consider whether a psychiatric disorder such as depression is causing patients not to visit their doctors. Especially in males or in 19- to 44-year-old adults, if the person did not visit the clinic despite the need (i.e., shows decreased health-seeking behaviors) then the clinician would suspect whether he/she might be depressed and consider performing simple screening tests such as the PHQ-9.

However, it is important to note that this study had several limitations. First, since it has a cross-sectional design, it was hard to investigate causation between depression and health-seeking behaviors. Second, the validity of the questionnaire for health-seeking behaviors was not fully verified, and there was only one related question in this study; therefore, while it was possible to determine decreased health-seeking behaviors, it was difficult to determine increased health-seeking behaviors. In addition, those individuals who answered “yes” to the item, “Have you ever been unable to go to the clinic (except for dentistry) during the previous year?” were classified as those with decreased health-seeking behaviors. However, to clarify those who answered “yes” to this item actually displaying health-seeking behaviors, additional items might be needed. This item of the questionnaire did not distinguish between actual health-seeking behaviors, health information-seeking behaviors, and health-seeking intentions. Third, to determine the impact of accessibility on health-seeking behaviors, the distance between the medical facility and the residence of the participant should be treated as an independent variable. In this study, however, there was no corresponding item among the questionnaires that was used for KHNAHES, and the residences of the participants were simply divided into urban and rural. Fourth, although the characteristics of different diseases could affect health-seeking behaviors in various ways, the diseases of the participants were not considered. Fifth, although it was suspected that various psychiatric disorders besides depression may affect health-seeking behaviors, they could not be included in the study because there was no questionnaire about other diseases such as anxiety disorder or somatization disorder.

Nevertheless, this study used the large-scale epidemiological study data of the sixth and seventh KNHANES, which could represent South Korea’s whole population, and has the advantage of controlling medical illnesses as well as environmental factors and socio-cultural factors. Notably, South Korea’s health systems are the same across the country [40.41]. South Korea is also composed of a single ethnic group, and there are no significant cultural differences between regions and races. Therefore, it could be assumed that all participants share similar cultural taboos, preferences, and stigma. That is, the effects of cultural and systemic factors known to affect health-seeking behaviors would be minimized in South Korea. These are the strengths of this study.

In conclusion, we found a significant association between health-seeking behaviors and depressive symptoms in a large Korean population. These results suggest that individuals with decreased health-seeking behaviors would be encouraged to evaluated for depressive symptoms. Future prospective studies are needed to clarify the causal relationship between depressive symptoms and health-seeking behaviors with a questionnaire consisting of more validated and detailed items.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) repository, https://knhanes.kdca.go.kr/knhanes/main.do.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyungsook Hong, Tae-Suk Kim. Data curation: Jihye Oh, Hyungsook Hong. Formal analysis: Jihye Oh, Hyungsook Hong. Funding acquisition: Tae-Suk Kim. Investigation: Jihoon Oh, Tae-Suk Kim. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: Jihoon Oh. Resources: Jihoon Oh. Software: Jihoon Oh. Supervision: Tae-Suk Kim. Validation: Jihye Oh, Hyungsook Hong. Visualization: Jihye Oh, Hyungsook Hong. Writing—original draft: Jihye Oh, Hyungsook Hong. Writing—review & editing: Jihye Oh.

Funding Statement

None