Impact of Interpersonal Relationships and Acquired Capability for Suicide on Suicide Attempts: A Cross-Sectional Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study examined the path model predicting suicide attempts (SA) by interpersonal need for suicide desire, acquired capability for suicide, the emotion dysregulation, and depression symptoms in people admitted to hospitals for medical treatment.

Methods

A total of 344 participants (200 depressed patients with attempted suicide, 144 depressed patients with suicidal ideation) were enrolled for this study. Depression, anxiety, emotion regulation, interpersonal needs, and acquired capability for suicide were evaluated. A model with pathways from emotion regulation difficulties and interpersonal needs to SA was proposed. Participants were divided into two groups according to the presence of SA or suicidal ideation.

Results

Acquired capability for suicide mediated the path from depression to SA. In the path model, difficulties in emotion regulation and interpersonal needs predicted depression significantly. Although depression itself was not significantly related to acquired capability for suicide, depression was significantly related to acquired capability for suicide in suicide attempter group.

Conclusion

Interventions with two factors affecting SA will clarify the suicide risk and contribute to finding risk factors.

INTRODUCTION

In South Korea, the suicide rate is remarkably high. According to a report compiled by the Korea National Statistical Office, in 2019, 26.9 persons per 100,000 population were victims of suicides [1]. Suicide is a leading cause of death worldwide with more than 800,000 people committing suicide every year [2]. Most suicide do not happen abruptly or accidentally and is an endpoint of a trajectory called the suicidal process [3].

Notably, all people with suicidal thoughts or ideation do not attempt suicide and only a fraction of those who attempt suicide are died by suicide [4]. Recent studies analyzing the factors affecting suicidal ideation have reported that a lack of social networks and support as interpersonal factors have a significant impact on suicidal ideation [4-6]. The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS) specifically predicts that acquired capability, perceived burdensomeness, and low belongingness are collectively necessary and sufficient proximal causes of serious suicidal behavior [7]. Furthermore, the most dangerous form of suicide desire is caused by the simultaneous presence of two interpersonal constructs: thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness [4].

However, the capability to engage in suicidal behavior is separate from the desire to engage in suicidal behavior. The acquired capability for suicide, or the capability to attempt suicide, leads to actual suicide attempts (SA). It is possible to acquire this capability, characterized by increased physical pain tolerance and reduced fear of death, through repeated exposure to physically painful and/or fear-inducing experiences [8,9]. Thus, through repeated practice and exposure, an individual can habituate to the physically painful and fearful aspects of self-harm/destructive behaviors, enabling them to engage in increasingly painful, physically damaging, and lethal forms of self-harm [4]. This is the hypothesis that the process leads to SA in the interpersonal theory of suicide.

Recent studies reported that self-harm behavior and acquired capability for suicide are not only related to SA [4,9,10], but in fact predict SA [11]. Within the framework of IPTS [4], interaction between suicide desire, influenced by two interpersonal need factors such as thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, and acquired capability for suicide predicts suicide attempt. However, a recent longitudinal study revealed that suicide desire was associated with acquired capability for suicide a year later [12], suggesting that suicide desire could act as a predictor for acquired capability for suicide.

In addition, suicide attempters reported significantly higher levels of affect dysregulation [13] and difficulties in regulating mood seemed to increase the risk of suicide [14]. A recent longitudinal study revealed that emotion dysregulation predicted suicide desire and the capability for suicide over time [12].

Although a recent study reveal the causal relationship between capability to self-harm and SA [15], the causal relationship between acquired capability for suicide and SA has not been fully demonstrated due to the time gap between these two. In fact, most previous studies on suicide have been conducted on clinical groups including suicide ideators with no suicide attempters or including only a few suicide attempters [6,15,16]. Several studies conducted with suicide attempters failed to verify the causal relationship between the acquired capability for suicide and suicide attempts [17] by including both lethal and nonlethal SA [18] or restricting to specific age groups, such as children and the elderly [15,19].

Therefore, this study aims to examine the comprehensive model predicting the suicide attempt by interpersonal need—thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness—for suicide desire, acquired capability for suicide, the emotion dysregulation, and depression symptoms for in people admitted to the hospital for medical treatment after attempted suicide by conducting path analyses.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 344 participants were enrolled between September 2017 and March 2020. Six individuals were excluded due to insufficient responses, leaving a final sample of 338 participants, which is larger than the standard minimum sample size for multi-group modeling analyses [20]. Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) with SA were recruited from the psychiatry department, and those with SA were also referred by the medical or emergency department of Soonchunhyang Cheonan Hospital after lethal SAs, such as drug intoxication, wrist cutting, hanging, or falling. Depressed patients with suicide ideation (SI) were recruited from the psychiatric outpatient clinic. The MDD patient groups were diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition Axis I Psychiatric Disorders [21]. Additionally, depressed patients with SI were enrolled after a psychiatric interview to confirm their SI and intent using the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation [22]. Diagnosis was confirmed by interview with two psychiatrists (JSK, SHS). None of these patients suffered from severe medical illnesses, mental retardation, or alcohol abuse. This study and all its experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Soonchunhyang University Cheonan Hospital (approval number: 2016-10-021). The study was performed in accordance with approved guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Psychological measures

Depression and anxiety symptoms were evaluated using the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) [23] and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) [24], respectively. The SDS is a validated scale comprising 20 items for measuring the severity of depressive symptoms [25]. Each SDS question is scored from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depressive symptoms. The BAI consists of 21 self-reported items scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, and raw scores range from 0 to 63 [24]. The BAI is an anxiety assessment scale that measures the intensity of cognitive, affective, and somatic anxiety symptoms experienced during the last seven days [24].

Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale (ACSS) was used to assess acquired capability for suicide [26]. ACSS is a 20-item self-report scale designed to assess levels of fearlessness about death, pain tolerance, and painful and provocative events [27]. The Korean version of the ACSS has been adapted and validated [28].

The Korean version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire for measuring difficulties in emotion regulation [29]. Each DERS question is scored from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater difficulties in emotion regulation [29].

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ) is a self-report measure of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, which represent suicide desire five. It consists of 15 items scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, and the Korean version of the INQ has good validity [30].

Statistical analysis

The normality of variables in each group was tested before further analysis. Skewness >2.0 and kurtosis >7.0, were considered to reflect a moderately non-normal distribution [31]. All variables in our study were within the normal distribution range. In all participants, suicide attempters were coded as 1 and suicide ideators were coded as 0 to make an additional variable called “suicide attempt” using dummy coding. Correlation analyses were performed to examine the relationships among demographic and psychological characteristics, including SA.

Based on the correlation results, a model was hypothesized. In the hypothesized model, emotion dysregulation can predict interpersonal needs and depression, interpersonal needs can predict SA through acquired capacity for suicide, and depression can also predict SA. There are two alternative models. In one model, emotion dysregulation can predict interpersonal needs and depression, and depression can predict SA through acquired capacity for suicide. In another model, emotion dysregulation can predict interpersonal needs and depression, and both depression and interpersonal needs predict the acquired capacity for suicide and SA. This study examined the hypothesized relations in the previously mentioned models by generating 1,000 bootstrapped samples for multiple comparison [32] using AMOS 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for path analyses [33]. Other statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM Corp.).

To determine better model fit, path analyses were performed with the maximum likelihood estimator using AMOS 21.0. The chi-square test (χ2), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) indices were used to examine the goodness of fit of the models. The cutoff points of the indices was >0.90 for CFI, NFI, TLI, and <0.08 for RMSEA [34]. For model comparison, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) index was used. The significance level was set at p<0.05.

Additionally, analysis was also conducted to determine whether the pathway was different between suicide attempters and ideators. An independent t-test was used to compare the psychological data scores between the two groups.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses

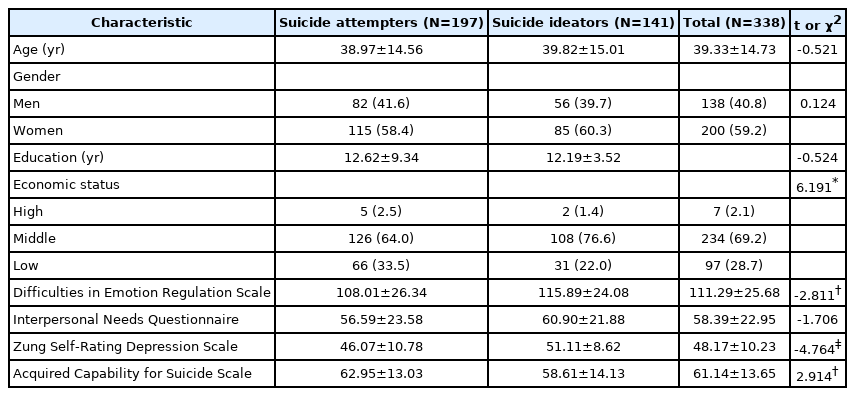

This study’s participants included 197 depressed patients with SA (82 men and 115 women) with a mean age of 38.97±14.56 years and 141 depressed patients with SI (56 men and 85 women) with a mean age of 39.82±15.01 years. The descriptive and psychological characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

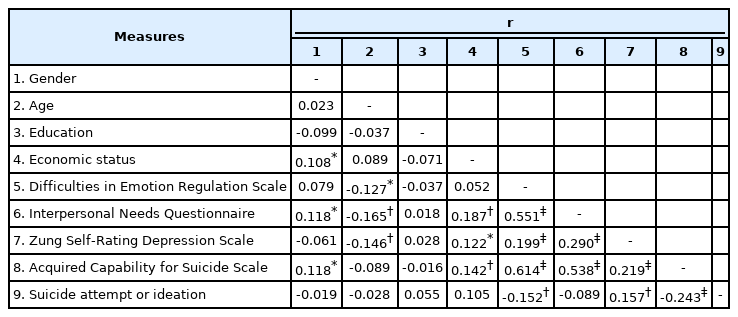

To analyze the relationship among difficulties in emotion regulation, interpersonal needs, and other psychological measures correlation analyses were conducted by each group, since scores of each group were within the range of normal distribution. As shown in Table 2, correlation analyses of all psychological measures and demographic variables were performed. Additionally, the correlation coefficients of psychological measures were significant, and the relationship between the following were also significant: gender and interpersonal need; age and difficulties in emotion regulation, interpersonal need, and depression; economic status and interpersonal need, depression, and acquired capability for suicide. Therefore, gender, age, and economic status were set as covariates, and significant relationships between covariates were also included in the models for further analyses.

The hypothesized model for path analysis was set based on previous studies and our correlation results for all participants. The hypothesized and alternative models comprised a path from emotion regulation, interpersonal needs, and acquired capacity for suicide to SA, in line with previous studies [4,7,35]. The two alternative models also comprised a path from emotion regulation, interpersonal needs, and acquired capacity for suicide to SA; the alternative model 1 suggests a fully mediating effect while the alternative model 2 suggests partial mediating effect of depression on the relationship between interpersonal needs and acquired capability for suicide. All models are shown in Figure 1.

Path analyses

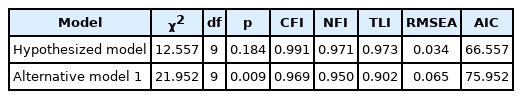

To reveal a better fitting model, the hypothesized model and alternative model 1 were examined and compared with the AIC score of the total participant pool. The AIC score of the first hypothesized model was 66.557, while that of alternative model 1 was 75.952. The first hypothesized model fits the data better than the second alternative model 1 because its AIC is much lower than that of the first model. Thus, the first hypothesized model is accepted. Alternative model 2 had a non-significant path between depression and acquired capacity for suicide (β=0.084, p=0.169), so it turned out to be the same as the hypothesized model. Therefore, only the hypothesized model and alternative model 1 are compared.

As shown in Table 3, the results of the path analyses of the models showed a great fit. To reveal the better fitting model, two models were examined and compared with the AIC score with the total participant pool. The AIC score of the hypothesized model was 66.557, while that of alternative model 1 was 75.952. The hypothesized model fits the data better than alternative model 1 because its AIC is much lower than that of the first model. Therefore, the hypothesized model is accepted.

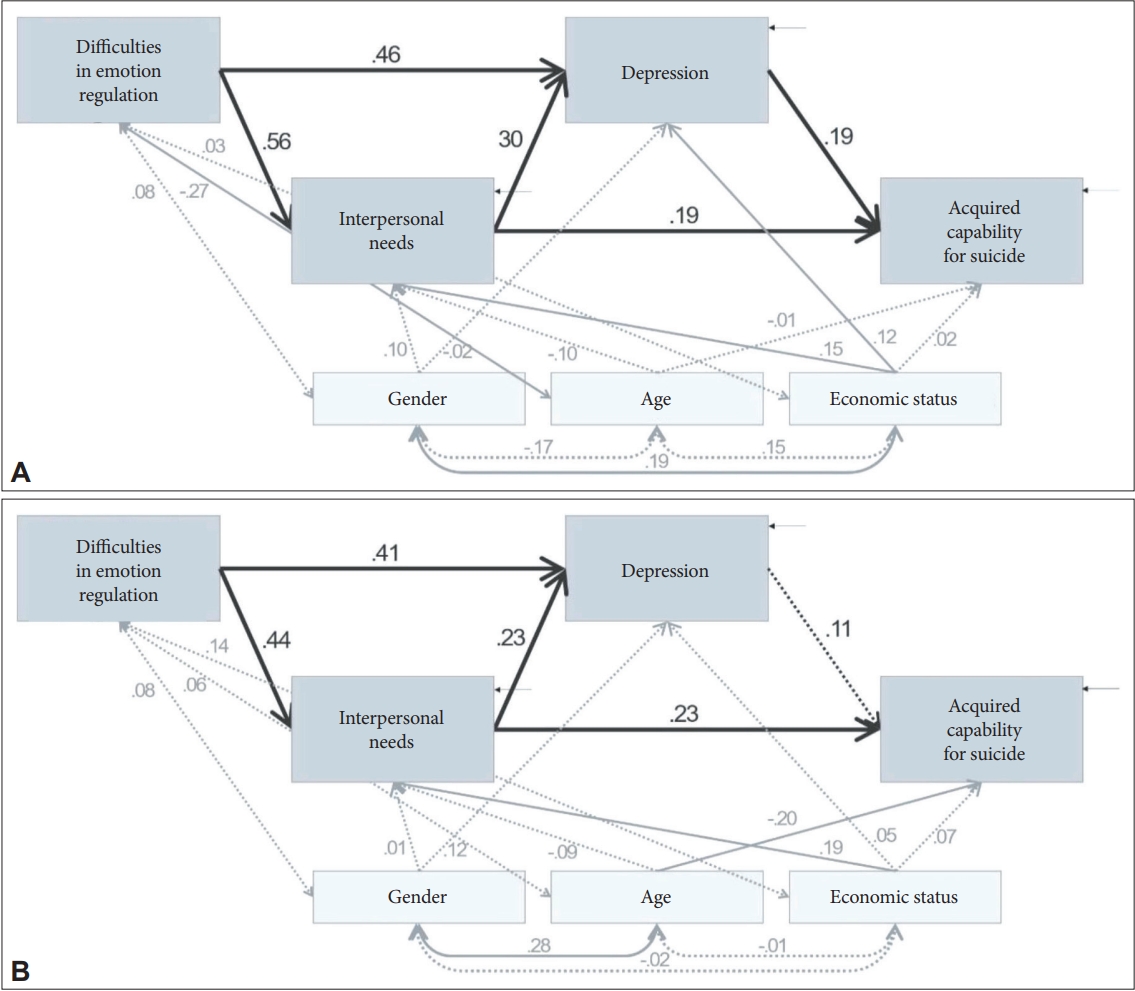

Figure 2 presents the accepted model with significant paths and standardized parameter estimates. Difficulties in emotion regulation significantly predicted interpersonal needs and depression (β=0.52, p<0.001; β=0.46, p<0.001, respectively). Moreover, the score for interpersonal needs significantly predicted depression and acquired capability for suicide (β=0.27, p<0.001; β=0.26, p<0.001, respectively). However, the scores of acquired capability for suicide were not significantly predicted by depression scores in all participants. Depression scores and acquired capability for suicide significantly predicted SA (β=-0.29, p<0.001; β=0.22, p<0.001, respectively). Therefore, a smaller score for depression and a larger score for acquired capability for suicide predicted SA rather than SI. Table 4 shows the regression weights, standard errors, and consistency ratios of the final model.

A comprehensive model from difficulties in emotion regulation to interpersonal needs, depression, acquired capability for suicide and suicide attempts in the participants.

Subsequently, additional path analyses were performed on two groups, suicide attempters and ideators, separately. As stated above, the depression score was negatively related to SA and not related to acquired capability for suicide. These relationships between depression and other variables could be different among suicide attempters and ideators, since those two groups showed significantly different depression scores (46.07±10.78, 51.11±8.62, respectively). Therefore, path analyses was conducted separately for the two groups to determine whether the model was different between the groups with SA and SI, using the final model but without the suicide attempt variable. Although the path between depression and capability for suicide was not significant in the final model for all participants, we decided to include this path to determine possible differences related to depression between the two groups. Figure 3 presents the model with significant paths and standardized parameter estimates for the two groups separately. Table 5 shows the regression weights, standard errors, and consistency ratios of the two models for the two groups. Focusing on the difference between the two groups, the depression score significantly predicted acquired capability for suicide (β=0.189, p<0.050) in the group with SA. However, depression scores did not significantly predict acquired capability for suicide (β=0.114, p=0.190) in the group with suicide ideators.

A comprehensive model from difficulties in emotion regulation to interpersonal needs, depression, acquired capability for suicide and SA in groups with SA and suicide ideators. A: Suicide attempts (SA). B: Suicide ideators.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the current study was to explore two interpersonal need factors—thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness—and acquired capability for suicide by using the path model analysis in depressed patients admitted to the hospital requiring medical treatment after a lethal suicide attempt and those with only SI. A path analysis was conducted to identify the impact of emotion regulation, mood symptoms, interpersonal state, and acquired capability for suicide on suicide attempt and ideation. Importantly, the “IPTS-a functional model of the acquired capability for suicide,” developed by Joiner [4,36] as an integrated model for SA, was supported with an optimal level of model fit through a questionnaire survey following the SA.

To the best our knowledge, this is the first study to prospectively test IPTS with a sample immediately after a lethal suicide attempt. In the study, we tested the link between emotion regulation, interpersonal needs, depression, acquired capability for suicide, SI and SA.

According to previous studies [37,38], suicidal ideation may be higher in individuals with depression, but SA may be related not only to depression but also to other psychological factors, including impulsiveness. Consistent with the current study’s findings that the difficulties in emotion regulation significantly predicted interpersonal needs and depression, Higgins and Pittman [39] state that emotion regulation is critical for human socialization; similarly, Eisenberg et al. [40] posit that emotion regulation is a social process by which people are influenced by others’ reactions.

In the present study, the score for interpersonal needs significantly predicted depression and acquired capability for suicide. Consistent with these findings and according to Joiner’s theory [36], interpersonal needs (perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness) appear to be more proximal predictors of suicidal ideation than depression. Additionally, both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness have been shown to be strongly related to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation [9,41-43]. Although beliefs about thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness may contribute to suicidal ideation beyond the effects of depression, it seems likely that depression may be related to an increase in such beliefs. Consequently, these negative interpersonal beliefs may serve as intermediary proximal factors that indirectly predict the effects of depressive symptoms on suicidal ideation.

We identified that the scores of acquired capability for suicide were not significantly predicted by depression scores in all participants. Unlike our results, Smith et al. [17] suggested that an individual can develop the capability for suicide in the heat of the moment via intoxication, psychosis, and so forth. Consistent with this result, depressive symptoms were not significant predictors of acquired capability scores [9].

In a comprehensive model including both suicide attempters and ideators, the present study identified several surprising findings. The interpersonal needs increase the acquired capability for suicide, thereby leading to SA. The acquired capability for suicide significantly predicted SA. Taken together, interpersonal needs significantly predicted SA. However, this is explained implicitly, and the acquired capability for suicide and depression are mediators. On the contrary, interpersonal needs increased depression, and depression decreased SA, but increased suicidal ideation. Despite being surprising and contrary to our knowledge, the current results showed that the severity of depressive symptoms in suicide attempters was significantly lower than that in suicide ideators. The cathartic effect of suicide is traditionally defined as the existence of a rapid, significant, and spontaneous decrease in the depressive symptoms of suicide attempters after the act. Patients hospitalized for less than 24 hours after a deliberated overdose revealed a significant reduction in depression [44].

In fact, the IPTS variables have been found to contribute to the prediction of suicidal ideation above and beyond the effects of other risk factors such as hopelessness [6] and depressive symptoms [9]. In the present study, the severity of depressive symptoms in suicide attempters were significantly lower than that in suicide ideators. Depression did not predict the acquired capability for suicide significantly. However, it predicted only SI, not suicide attempt.

As depression severity between depressed patients with SA and SI was significantly different, and the scores of acquired capability for suicide were not significantly predicted by scores of depression in all participants, we tried to separate the two groups for further analysis. Consequently, in the group with SA, the depression score significantly predicted the acquired capability for suicide. However, in the group with suicidal ideation, the depression score did not significantly predict the acquired capability for suicide. Taken together, suicidal ideation increases when depression worsens, and SA increase with acquired capability for suicide. In suicide attempters, even if depression is less severe, the acquired capability for suicide affects SA. In suicide ideators, depression did not significantly predict acquired capacity for suicide. In such cases, even if the depression was severe, it was predicted to be suicidal ideation, rather than a suicide attempt.

This study has some limitations. First, cross-sectional design of this study limits the conclusions regarding the causal relationships of the model. Further studies with longitudinal design should be done to support our findings. In addition, the participants in this study were recruited from a single hospital, which may limit the generalizability and applicability to other populations. Finally, participants with other disorders beside MDD were excluded due to improve the internal validity. More studies on SA in people with other disorders including bipolar disorder should be done to generalize these findings.

In conclusion, the current study examined a comprehensive model explaining relationships among interpersonal need for suicide desire, acquired capability for suicide, the emotion dysregulation and depressive symptoms related to suicide attempt by conducting path analyses. Initially, difficulties in emotion regulation predicted both interpersonal needs and depression, and both depression and acquired capability for suicide act as mediators between interpersonal needs and SA/SI; acquired capability for suicide predicted SA, while depression predicted SI. In addition, depression significantly predicted acquired capability for suicide only in suicide attempter group, but not suicide ideator group. These results suggests that interventions with difficulties in emotion regulation and interpersonal needs affecting SA will clarify the suicide risk and contribute to finding risk factors. It will also help reduce suicide rates through interventions in the processes leading to SA by identifying variables to predict the attempts through the path to SA.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Se-Hoon Shim, Ji Sun Kim. Data curation: Ji Sun Kim. Formal analysis: Min Jin Jin. Funding acquisition: Se-Hoon Shim. Investigation: Ji Sun Kim. Methodology: Min Jin Jin. Project administration: Se-Hoon Shim, Ji Sun Kim. Resources: Se-Hoon Shim, Ji Sun Kim. Software: Ji Sun Kim, Min Jin Jin. Supervision: Se-Hoon Shim, Young Joon Kwon, Dongwook Lee, Ho Sung Lee. Validation: Se-Hoon Shim, Young Joon Kwon, Dongwook Lee, Ho Sung Lee, Ji Sun Kim, Min Jin Jin. Visualization: Min Jin Jin. Writing—original draft: Se-Hoon Shim. Writing—review & editing: Ji Sun Kim, Min Jin Jin.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Jisan Cultural Psychiatry Research Fund and a grant (2020R1I1A3A04036435) awarded by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and funded by the Ministry of Education. This study was also supported by Soonchunhyang University.