Development of a Checklist for Predicting Suicidality Based on Risk and Protective Factors: The Gwangju Checklist for Evaluation of Suicidality

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The aim of the study was to develop a checklist for mental health clinicians to predict and manage suicidality.

Methods

A literature review of the risk and protective factors for suicide was conducted to develop a checklist for evaluating suicidality.

Results

The fixed risk factors included sex (male), age (older individuals), history of childhood adversity, and a family history of suicide. Changeable risk factors included marital status (single), economic status (poverty), physical illness, history of psychiatric hospitalization, and history of suicide attempts. Recent discharge from a mental hospital and a recent history of suicide attempts were also included. Manageable risk factors included depression (history and current), alcohol problems (frequent drinking and alcohol abuse), hopelessness, agitation, impulsivity, impaired reality testing, and command hallucinations. Protective factors included responsibility to family, social support, moral objections to suicide, religiosity, motivation to get treatment, ability to cope with stress, and a healthy lifestyle. A final score was assigned based on the sum of the risk and protective factor scores.

Conclusion

We believe that the development of this checklist will help mental health clinicians to better assess those at risk for suicidal behavior. Further studies are necessary to validate the checklist.

INTRODUCTION

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. The suicide rate for the Republic of Korea is the highest among all Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development countries over the past decade [1]. Suicide is the fifth-leading cause of death in Korea. Thus, suicide is a major public health problem, and its prevention is a public health priority [2].

To prevent suicide, it is important to be able to assess and predict the risk thereof. Numerous studies have attempted to identify suicide risk factors for the prediction and prevention of suicide [3]. Studies have shown that suicide risk is associated with biological, psychological, social, and environmental factors [4]. However, given the complex nature of suicidal behavior, the multitude of factors involved, and the dynamic interactions among them, predicting suicidality can be a difficult undertaking [5]. In addition, a relatively low incidence of suicidal deaths has limited the feasibility of developing a valid scale for assessing suicidal risk, which is further compounded by a lack of specificity.

Suicidality can be managed by reducing the factors that promote or precede suicidal behavior, and enhancing protective factors that inhibit suicidal behavior [6]. Suicidal risk and protective factors are closely associated, and comprehensive assessment of these factors is important for timely intervention. One of the most commonly used instruments is the SAD PERSON scale, which is a 10-item scale designed to have high content validity [7]. However, a systemic review found insufficient evidence to support its use for predicting suicide [8,9]. A well-validated and easily accessible tool to help Korean clinicians evaluate suicidality is necessary. The aim of the current study was to develop a checklist of risk and protective factors for suicide, for use by mental health clinicians, based on evidence from the literature (including studies conducted in Korea).

METHODS

We developed the Gwangju Checklist for Evaluation of Suicidality (G-CES) based on clinical interviews to evaluate suicidality risk. First, we searched the literature to identify factors associated with suicidality. Based on earlier studies, including ones conducted in Korea, we complied a checklist of items for suicidality evaluation. The items of this checklist were broadly classified into two types: risk and protective factors. Risk factors were then classified into subfactors based on whether they were fixed (internal/demographic), variable (changeable over time), or manageable (through intervention). We then evaluated potential protective factors against suicidal behaviors.

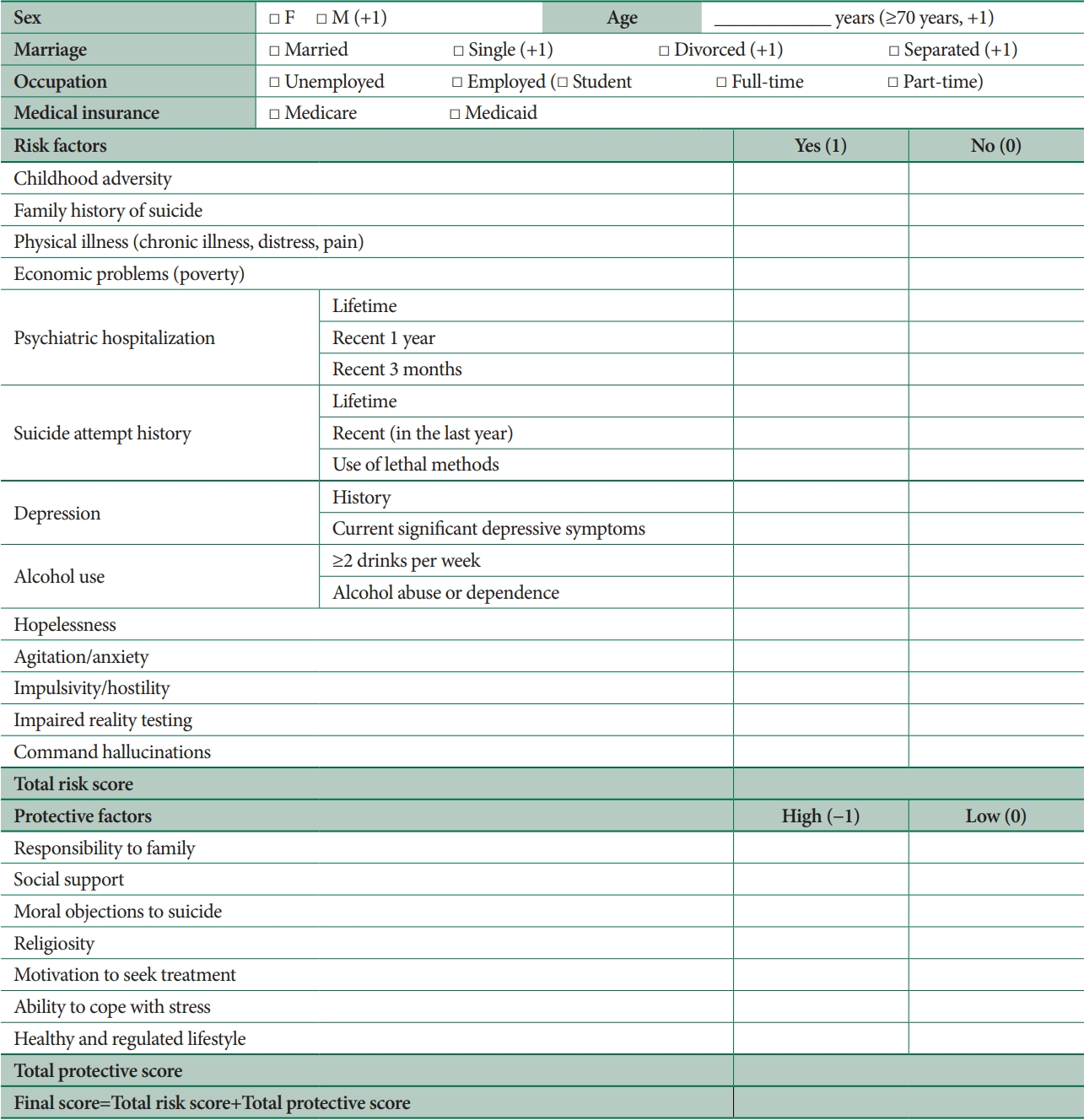

The preliminary version of the G-CES used 2- and 4-point Likert scales [10]. However, after analysis of the initial data and discussions with clinicians and other stakeholders, we simplified the scale into a “yes/no” checklist format. The final checklist score is calculated as the sum of the risk and protective factor scores. The risk factors were assigned a value of “0” (no effect/not applicable) or “1” (yes), depending on whether the risk factor was present. The protective factors were assigned a score of “-1” (high/strong protection) or “0” (low/no effect). The clinical significance of the score is currently under review for validation purposes. Here, we present G-CES version 1.1, which we expect to modify based on the validation analyses and additional studies. However, even before the final validation, we expect that mental health clinicians will find this checklist helpful when interviewing patients at risk for suicidal behavior; the checklist may also be useful for assessing longitudinal changes within individuals. The Institutional Review Board of Chonnam National University Hospital approved this study (no. TMP CNUH-2019-013).

RESULTS

Figure 1 lists the checklist items for the G-CES.

Fixed risk factors

Fixed risk factors included demographics and a clinical history of factor/s associated with an elevated risk of suicide. It is important to identify such factors when assessing suicidality, even though they cannot be changed. Here, the fixed risk factors were sex (male), age (older individuals), childhood adversity history, and family history of suicide.

Sex (male)

Suicide rates are higher among males than females in most countries, although suicide attempts are more common in females. Many studies have explained the gender gap in suicidal behavior in terms of lethality. Males are more likely to die when they attempt suicide because their suicide methods are more lethal; they also show a stronger intent to die than females [11]. In Korea, the male suicide rate is more than twice that of females [12].

Age (older individuals)

The suicide rate generally increases with age [13]. Many studies have reported that older people are at a greater risk of suicide [14,15]. Suicide risk is especially high for elderly males in Korea [2]. Predictors of suicide in older individuals include psychiatric disorders, physical illness, economic problems, functional impairment, and stressful life events [16].

Childhood adversities

Exposure to childhood adversity is a strong and independent risk factor for suicidal behavior [17,18]. Adverse childhood experiences can increase the risk of suicide attempts two- to five-fold. Early life trauma significantly increases the likelihood of suicidality throughout the life span [19]. Surveys have demonstrated that exposure to childhood physical or sexual abuse, or the witnessing of domestic violence, accounts for 50% and 33% of suicide attempts among women and men, respectively [20]. Our previous studies of the Korean general population and patients with schizophrenia and depression showed significant associations between childhood adversity and suicidal behavior [21-24]. Abuse in childhood may promote suicidal behavior in adulthood through heightened trait impulsivity, the family dynamics associated with childhood adversity, and psychiatric disorders including substance use disorder and depression [19,25,26]. For these reasons, it is extremely important to thoroughly assess the history of childhood adversity to mitigate suicidal behavior.

Family (first degree relative) history of suicide

Suicide and suicidal behavior often have familial tendencies and appear to be heritable. This may be associated with a family history of psychiatric disorders, impulsive aggression, or environmental factors such as abuse, imitation, or transmission of psychopathology [27]. A family history of suicide is an independent predictor of suicidality, i.e., is independent of mental disorders [28]. Genetic risk factors for suicide have also been examined [4,29].

Changeable risk factors

Changeable/variable risk factors are those that can change in severity over time but are not direct targets for psychiatric intervention and management. They include marital status (single), economic status (poverty), physical illness, history of psychiatric hospitalization, and a history of suicide attempts. While a history of suicide attempts or psychiatric hospitalizations obviously cannot be changed, these factors were classified as changeable herein given the nature of the checklist, which is concerned with the 3-month or 1 year period after the occurrence of an event/discharge).

Marital status (single)

Marital status is associated with the risk of suicide; divorced and separated individuals are the most likely groups to commit suicide in both Western and Eastern countries [30,31]. Living with a spouse can exert a protective effect against suicide [32-34]. Durkheim hypothesized that marriage promotes social integration and a more supportive social network [35]. Single status showed a stronger association with suicidality than being married in our previous study conducted in the Korean general population [36].

Economic problems (poverty)

Low socioeconomic status is directly associated with a higher risk of suicide and suicide attempts [37,38]. In previous Korean studies analyzing suicide mortality data, the hazard ratios of suicide showed an increasing trend with lower socioeconomic status [39], and the suicide rate was higher in areas where more Medicaid recipients lived [40]. In our previous study on the factors associated with suicide attempts in the general population, Medicaid recipients with low poor economic status were six times more likely to attempt suicide than people with Medicare general insurance [36]. Personal financial problems and unemployment have been reported to be associated with suicidality [37,41], similar to economic crises and inequalities [42].

Physical illness

Previous studies have reported that people who suffer from physical illness and pain are at an increased risk for suicidal behavior [43-46]. Clinical depression is a strong predictor of elevated suicide risk among physically ill people [47]. Furthermore, suicide risk is highly elevated in cases of concurrent physical and psychiatric illnesses [44]. Some studies have shown that nearly all physical health conditions are associated with increased suicide risk, even after adjustment for potential confounders [45,48].

History of psychiatric hospitalization

Many studies have reported that the risk of suicide is heightened after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care [49-51]. The incidence of post-discharge suicide is higher closer to the time of discharge [52]. Suicide risk is especially high within the 3-month period after psychiatric discharge [49,51,53,54]. Additionally, the suicide rate remains high for many years after discharge [51]. Thus, patients who have recently been discharged from a psychiatric hospital should be closely monitored for suicide risk [55]. Suicide soon after discharge is associated with a more severe psychopathology, poorer functioning, and use of more lethal and easily available methods [56]. In the G-CES, items pertaining to suicide after discharge from a psychiatric hospital are scored based on the time therefrom (3 months, 1 year, or lifetime). Thus, history of psychiatric hospitalization has a weighted score.

Previous suicide attempt

A previous suicide attempt is a strong predictor of future attempts and completed suicides [8,57]. Suicide is more common among previous attempters than non-attempters [58]. Studies of risk factors for suicide consistently suggest that a history of suicide attempts is the most salient risk factor for current suicidality [54,59,60]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition includes a new diagnostic category, i.e., suicidal behavior disorder, which captures the history of suicide attempts [61]. Suicide attempts with a highly lethal method, and recent suicide attempts, are strongly associated with the risk of suicide. Thus, the G-CES includes multiple items pertaining to a history of suicide attempts, including items on lifetime, recent, and use of lethal methods during attempts.

Manageable risk factors

Risk factors that can be managed are state risk factors, in this case for suicide, which should be targeted by clinical interventions. They include depression, alcohol problems, hopelessness, agitation, impulsivity, impaired reality testing, and command hallucinations.

Depression

Major depression is the most common underlying psychiatric condition of people exhibiting suicidal behavior [36,62]. A recent systemic review of psychological autopsy studies of suicide victims showed that major depressive disorder, dysthymia, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia were significantly associated with suicide risk [63]. Suicide attempters with bipolar disorder had experienced more lifetime episodes of major depression; moreover, twice the number of attempters compared to non-attempters were currently experiencing depressive or mixed episode [64]. Multiple mental disorders greatly increases suicidal risk [65,66]. The risk of attempted suicide is particularly high in the first 3 months after the onset of a major depressive episode, and in the first 5 years after the onset of major depressive disorder, independent of the duration of depression [67]. Dysfunction of the serotonin system, which is involved in impulsive and aggressive traits and depressive disorder, is associated with suicidal behavior [68]. Additionally, the risk of suicide increases with the severity of depression [60,67]. Thus, the G-CES includes two items pertaining to depression, i.e., one that focuses on the history thereof and another focusing on current significant depressive symptoms.

Hopelessness

In most empirical investigations of suicide, hopelessness has been identified as the most reliable psychological risk factor and clinical endophenotype [25,68]. Hopelessness mediates the relationship between suicidal ideation and suicidal acts, and reduces the desire to live in the face of distress [69]. Individuals with high levels of hopelessness may isolate themselves and exhibit less help-seeking behaviors [70]. As such, hopelessness is a major predictor of suicidality, especially in patients with psychiatric disorders and the elderly [25,67,71].

Agitation or anxiety

Agitation may be a warning sign and acute risk factor for suicidal behavior [72,73]. Agitation further increases the risk of suicide in patients with depressive symptoms or schizophrenia [74,75]. Anxiety symptoms and disorders have consistently been associated with an elevated risk of suicidal behavior in community cross-sectional and clinical studies [76,77]. Suicide risk is also closely associated with the severity of panic/agoraphobia, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and obsessivecompulsive symptoms.

Alcohol problems

Suicide risk is high in people with alcohol problems; those suffering from alcohol use disorder were 60–120 times more likely to attempt suicide compared to the general population [78]. Moreover, a positive breathalyzer test is common among individuals who completed (up to 69%) or attempted (up to 73%) suicide [79]. Social drinking, i.e., drinking not satisfying the criteria for addiction, can also increase suicidality [80]. Alcohol consumption predisposes individuals to suicidal behavior through its depressogenic effects, impairment of problemsolving skills, and exacerbation of impulsivity, possibly through its effects on serotonergic neurotransmission [81,82]. Comorbid alcohol problems also increase the risk of suicide when cooccurring with other psychiatric disorders such as depression and schizophrenia [66]. In previous studies on the Korean general population, hazardous alcohol consumption was associated with previous suicide attempts and suicide deaths [36,40,83,84]. The G-CES includes two items on alcohol problems: frequency of alcohol consumption and alcohol use disorders.

Impulsivity and aggression

Impulsivity and aggression are highly correlated with suicidal behavior in psychiatric and general populations [85]. Impulsivity may mediate suicidal behavior in younger people, and in patients with alcohol use, personality, or psychotic disorder. Individuals with high levels of impulsivity cannot manage their behavior or make appropriate decisions [86]. Greater impulsivity and impaired decision-making may underlie the tendency toward suicidal and aggressive acts [87]. Impulsivity is an important predictor of suicidal behavior, as it may precipitate suicide ideation and suicidal action [69].

Impaired reality testing

Impaired reality testing, sometimes in the form of delusions, in various psychiatric illnesses (including psychotic disorders) may promote suicidality [88-90]. Approximately 2%–12% of all suicides are attributable to schizophrenia [91]. Suicide is a cause of early mortality in nearly 5% of patients with schizophrenia, and 25%–50% of patients with schizophrenia attempt suicide in their lifetime [92]. In addition, when reality testing is impaired, various conditions can reduce the ability to manage risky behavior and lead to suicidal behavior.

Command hallucinations

Auditory hallucinations are seen in various psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and alcohol withdrawal. Command hallucinations to kill oneself are common and can lead to suicidal behavior [89,93]. Thus, mental health clinicians should be aware of this type of hallucination [93].

Protective factors

There are also some protective factors against suicidality. In the G-CES, there are seven such factors: responsibility to family, social support, moral objections to suicide, religiosity, motivation to seek treatment, ability to cope with stress, and a regulated and healthy lifestyle.

Responsibility to family

Responsibility to family can reduce suicidality in patients with psychiatric disorders [94,67]. It enhances the motivation to live and degree of control over suicidal urges. In our previous study on the Korean general population, family cohesion was significantly negatively associated with a history of suicide attempts [83].

Social support

Many studies have reported that social support is associated with a decreased likelihood of a lifetime suicide attempt, while controlling for a variety of related predictors [95]. Strong connections with family and community support may protect against suicidal behavior [68,96]. In contrast, loneliness and living alone increase suicidality [97]. Another Korean study showed that low social support, and low frequency of family contact and leisure activities were associated with suicide attempts [36,37]. Our previous study on hospitalized patients with schizophrenia showed that the frequency of family visits to the hospital was inversely associated with suicidality [98].

Moral objections to suicide

Many view suicide as an immoral act. People who have a permissive attitude toward suicide or few moral objections thereto are more likely to have a history of suicide attempts and cite fewer reasons for living [99,100]. Meanwhile, people who have significant moral objections to suicide are more likely to have a religious affiliation and express less hopelessness [67,99,101].

Religiosity

The results of previous studies investigating the association between religious affiliation and suicide have been inconsistent. However, several studies have shown that high religiosity is associated with a substantially lower suicide risk, especially in clinical populations [102]. In recent longitudinal prospective studies, frequent attendance of religious services was an important protective factor against completed suicide over the long term [103,104]. Religious affiliation may lower aggression levels and promote moral objections to suicide, thus reducing suicidal behavior. In addition, religious commitments also promote social integration, meaningfulness, and healthier behaviors, and also reduce alienation [102,105]. However, this effect appears to be more significant in Western cultures that are religiously homogeneous [106]. In our previous study, religiosity was associated with fewer suicidal thoughts in psychiatric inpatients [10]. and less severe depression in patients with breast cancer [107]. Therefore, it is necessary to further investigate the potential protective role of religiosity against suicide.

Motivation to seek treatment

Because psychiatric disorders increase the risk of suicide, people experiencing these disorders must be treated appropriately to prevent suicide death. Poor adherence to psychiatric treatment is associated with increased suicidality [108], while motivation to seek psychiatric treatment may decrease suicidal behavior, as it provides a means of controlling psychiatric problems [93]. Therefore, when assessing suicidality in clinical populations, the patient’s motivation to seek treatment should be evaluated.

Ability to cope with stress

Life stress is associated with the onset of depression and suicide ideation; however, the ability to cope plays a mediating role [109,110]. People who have attempted suicide tend to have less useful coping strategies, such as avoidance. [111,112]. Problemfocused active coping strategies, in contrast, may protect against suicidality.

Regulated and healthy lifestyle

Lifestyle behaviors impact mental health and suicidal behavior by influencing emotions and judgement [113]. A sedentary lifestyle and addictive behaviors are associated with poorer mental health and suicidality [113,114], whereas increased physical activity and balanced life routines decrease suicidality [115]. Earlier studies of the Korean population showed that regular activity is a protective factor against depression and suicidal ideation [116,117].

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provide a rationale for the development of the G-CES, based on a literature review of the factors associated with suicidal behavior. The basic function of the G-CES is to predict and prevent suicidal behavior through comprehensive assessment of risk and protective factors. Risk and protective factors for suicide were derived from individual studies of variable quality and size. While some studies have shown that specific risk factors are important, others have provided equivocal results. These inconsistencies can be explained by the interactive effects of risk and protective factors for suicide. The G-CES includes the most replicable risk and protective factors.

The strengths of the G-CES are as follows: First, using this checklist during clinical interviews can help mental health clinicians obtain comprehensive data on people with suicidality, although clinicians must have the medical understanding necessary to appreciate the dynamic interactions among factors. Second, the G-CES includes not only risk factors for suicidality determined based on sociodemographic characteristics and clinical history, but also factors that can be changed or managed to mitigate behavior, as well as protective factors. Third, a score for the G-CES checklist can be calculated to aid prediction of suicidal behavior. Although validation is needed, the G-CES is expected to facilitate clinical decision-making regarding treatment and psychiatric hospitalization.

The limitations of the G-CES checklist are as follows: First, the definition of individual items may not be sufficiently clear. For example, social and clinical variables, such as economic problems, agitation, and impulsivity, are difficult to objectively define in terms of severity. However, given that the checklist was developed for mental health clinicians and screening interviews, clinical judgement could be exercised to assess severity. In addition, the items will be scored based on whether they are clinically significant or distressful to patients. Finally, at present there is insufficient clinical evidence to support the use of the G-CES scoring system, and some factors should have a weighted score if their associations with suicidality prove particularly strong. Therefore, the G-CES should be validated sufficiently before being applied for the prediction of suicidality; it may require further modification depending on the results of validation studies. We hope to publish the results of our retrospective review of medical records obtained from community mental health centers and psychiatric hospitals soon, for initial validation of the G-CES. We will then conduct a prospective longitudinal study of suicidality to further test it, in which algorithms will also be developed to aid clinical decision-making.

As well as risk and protective factors, suicidal ideation, plans, and intent are critical to suicidal behavior; even if a patient has few risk factors, if suicidal ideation or planning are present the risk of suicidality may be high. Thus, risk and protective factors should be considered together with suicidal ideation during clinical decision-making. After validating the G-CES, we will develop a clinical decision tree or algorithm taking account of the present level of suicidal ideation. In the future, the aim is to develop a scoring system through machine learning of extensive datasets, based on the G-CES.

In conclusion, it is important to investigate risk and protective factors for suicidal behavior. Suicide is highly complex and thus difficult to predict. Currently, the clinical tools available to mental health professionals in Korea are not sufficient for identifying those at risk for suicidal behavior. We believe that the G-CES will be helpful for clinicians in community mental health centers and hospitals, although validation studies are needed.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

Sung-Wan Kim, Jae-Min Kim, contributing editors of the Psychiatry Investigation, were not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Sung-Wan Kim. Funding acquisition: Sung-Wan Kim. Investigation: Woo-Young Park. Project administration: Min Jhon, Ju-Wan Kim, Hee-Ju Kang, Seon-Young Kim, Seunghyong Ryu. Supervision: Ju-Yeon Lee, Il-Seon Shin, Jae-Min Kim. Writing—original draft: Woo-Young Park, Sung-Wan Kim. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by a grant of Patient-Centered Clinical Research Coordinating Center (PACEN) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI19C0481, HC19C0316).