Structural Model Analysis of Discriminatory Behavior Toward People With Severe Mental Illness

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to determine how prejudice and attitude toward people with severe mental illness, formed through exposure to the mass media, affect discriminatory behavior toward them.

Methods

Between September and November 2019, demographic data were collected using an online survey of 622 adults residing in South Korea. The scales used in this study were taken from the 2008 survey by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea. Structural equation modeling was performed for a comparative analysis of the direct and indirect effects.

Results

Virtual experience through mass media exposure had a statistically significant effect on prejudice against people with severe mental illness. Direct experience had a positive influence on reducing prejudice and discriminatory behavior. The direct effects of prejudice on discriminatory behavior were significant. In terms of indirect effects, the full mediating effect of prejudice was significant for the virtual experience through the mass media-prejudice-discriminatory behavior path, and the partial mediating effect of prejudice was significant on the direct experience-prejudice-discrimination behavior path.

Conclusion

This study recommends more careful reporting of mental illness in the media, promoting anti-stigmatization programs that provide opportunities for direct contact between the public and people with severe mental illness.

INTRODUCTION

Prejudice against people with severe mental illness is a complex phenomenon arising from different social, cultural, and historical contexts [1]. In both academia and general debate, there is still controversy regarding the correlation between mental illness and crime [2]. While it is reported that their crime rate in the total number of crimes is lower than that of the general public [3], the risk of violent crime in schizophrenic patients without drug and alcohol abuse is 1.2 times more compared with that of the general population. The crime rate of schizophrenia patients increases 4.4 times in the presence of drug and alcohol abuse [4], and prevalence of murder, arson, and drug-related crimes caused by people with severe mental illness is also known to be high [2].

Mass media has often treated stories of violent crimes caused by people with severe mental illness with sensationalism, but seldom focused on turning the spotlight on the internal lives of such people or their recovery through treatment and rehabilitation [5]. Mass media has a duty to deliver accurate information about mental illness to the public. Nevertheless, depictions of violence or crimes committed by people with severe mental illness and biased reporting are disseminated through TV dramas and news media. This reinforces the prejudicial attitude that most people with severe mental illness should limit their social life, since they are dangerous people who can commit crimes [6,7]. In modern society, people consume information on daily life from mass media such as TV, the Internet, newspapers, and radio. Mass media is also where many people obtain information on health and medicine. Accordingly, the role of mass media is very important for the general public’s perception of mental illness [1].

Unprofessional and provocative reports of criminals with mental disorders deepen the prejudice against people with severe mental illness by reinforcing distorted perceptions of them [8,9]. This leads to people perceived as having a mental illness being stigmatized as objects of fear and disgust, which has a direct effect on discriminatory behavior against them [10,11]. Therefore, mass media needs to play an essential role in overcoming prejudice against them through more balanced reporting.

Prior studies have confirmed that the experience of meeting someone with a mental illness in person is effective in reducing the negative attitudes of the general population toward them [12,13]. Studies have shown that people who had no prior experience with people with severe mental illness maintained a distance from them, showcasing discriminatory behavior, while those who had prior experience showcased a significantly lower degree of discrimination [14,15]. However, as a person’s symptoms worsen, there are fewer opportunities to positively socialize with them in person. Nevertheless, in-person interactions with patients have shown a higher positive effect on improving public awareness about mental illness than public education, thereby bringing about a continued reduction in the stigma attached to it [16]. Thus, it is necessary to increase contact with people with severe mental illness.

Discrimination against patients with mental illness is a major obstacle to their reentry into the community after hospital treatment. This discrimination, in turn, encourages long-term hospitalization [17,18]. The government amended the Act on the Improvement of Mental Health and the Support for Welfare Services for Mental Health Patients in 2016 and implemented it in May 2017. An effort was made to improve the mental health of people, shorten the hospitalization period for people with severe mental illness, and provide community-centered rehabilitation and welfare services [19,20]. However, efforts at the national level, which emphasize the human rights and well-being of people with severe mental illness, may not bear fruit. This is possible only if the general public’s prejudice, negative attitude, and discriminatory behavior toward mental illness stop. Negative mass media coverage not only leads to discrimination, but also hinders the social adaptation of people with severe mental illness. Similarly, it distorts the general public’s understanding of mental illness and the options for treatment methods. Accordingly, a study on the effect of biased media coverage that leads to discriminatory behavior is needed. Moreover, there is a need for effective measures to reduce the stigmatization of mental illness. Such measures can be formulated by comparing and analyzing the differences in the effect that a virtual (through mass media) experience of mental illness and a direct (physically meeting someone with mental illness) experience has on prejudice and discrimination.

Regarding the effects of mass media on discriminatory behavior toward people with severe mental illness, this study covers new ground. Prior studies have focused on the analysis of mass media content or the analysis of simple correlations and linear relationships with influencing factors. [1,5]. These studies have used multidimensional structural equation modeling (SEM) to verify the relationship between prejudice and attitudes toward people with severe mental illness [7,9]. In this study, virtual experience through mass media, direct experience with people with severe mental illness, and prejudice are set as factors that affect discriminatory behavior, which is the dependent variable, and structural model analysis is conducted through direct and indirect effects analysis. Through this, basic data are provided for developing an intervention strategy to reduce prejudice and discriminatory behavior. Moreover, this study can be used to prepare a plan to implement a recovery paradigm for mental illness.

METHODS

Research subjects

This study forms a part of the “Survey on the actual situation of the implementation status of the national report on mentally challenged” by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea. It is an analysis of an online survey conducted between September 2019 and November 2019 with 622 adults residing across the country. In sampling using the online survey platform, men and women were proportionally allocated, and the distribution of age and region was randomly allocated. In addition, the online survey was conducted in a balanced manner by closing the survey when the number of samples for a specific group was met by periodically checking the distribution of gender, age, and region. This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee (IRB) of Ewha Women’s University (ewha-201908-0027-02). It was conducted after informed consent had been obtained from the subjects following a presentation of the purpose and procedure of the study.

Research tools

Discrimination against patients with mental health problems

Some items in the scale used in this study were first used in a survey on discrimination and prejudice against mental health patients carried out by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea in 2008 [21]. For this study, they were revised to achieve adequate grammar and specificity. This scale consisted of 13 items, including seven items on “avoidance of personal relationships” and six items on “deprivation of basic social rights.” The five-point Likert-type scale consisted of 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree. A high score was associated with a high level of unwillingness to be physically or psychologically close to people with severe mental illness. A high score indicated a belief that basic social rights, such as voting rights or custody of children, should not be given to people with severe mental illness. The reliability of the scale was very high (Cronbach’s α=0.907; 0.902 for the “avoiding personal relationships” factor and 0.787 for the “deprivation of basic social rights” factor).

Virtual experience through mass media

Five items on the scale investigated the causes of prejudice against people with severe mental illness. One of the items that asked where people believed their bias was formed referred to “the influence of mass media.” A five-point Likert-type scale was used: 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree. A high score was associated with a stronger influence of the mass media. Again, this was first used in the 2008 survey by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea [21].

Direct experience with persons with mental illness

Among the 2008 survey by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea, there were four items which were related to people with severe mental illness. The total score of these four items was considered. A high score signified a high degree of direct experience.

Prejudice against people with mental illness

Some of the items used in the 2008 “Survey on Discrimination and Prejudice against Mental Health Patients” by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea were revised for the purposes of this study [21]. Out of a total of 24 items, nine items were concerned with the “incompetence” factor, seven items measured the “risk” factor, five items were concerned with the “unrecoverable” factor, and three items investigated the “identifiable” factor. Participants were asked to respond using a five-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree). A high score indicated a high degree of bias. The scale’s reliability was very high (α=0.941; 0.916 for the “incompetence” factor, 0.877 for the “risk” factor, 0.749 for the “unrecoverable” factor, and 0.740 for the “identifiable” factor).

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics included gender, age, educational level, and marital status.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and AMOS 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used for data analysis in this study. Missing values were treated by the expectation-maximization method.

First, to measure the reliability of the scale, Cronbach’s α was calculated. Frequency analysis, mean, standard deviation, and normality analyses were then performed. Second, SEM was performed for comparative analysis of direct and indirect effects. To evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the model, goodnessof-fit indices such as χ2, comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic characteristics of study subjects

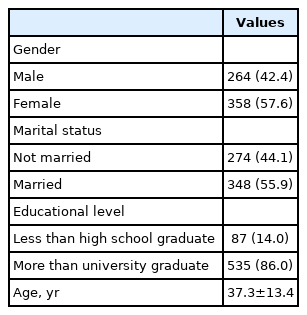

The demographic characteristics of the study subjects are shown in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of measurement variables

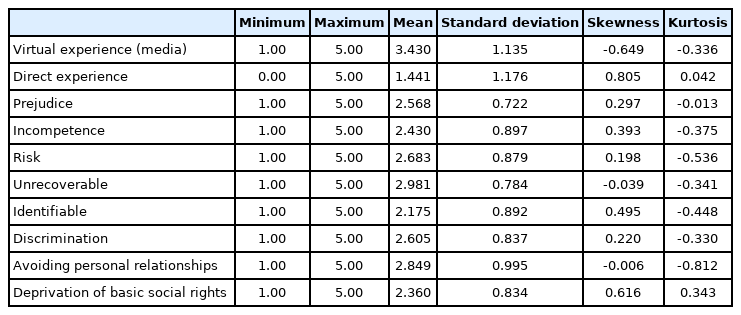

When the measurement variables are not normally distributed in the structural equation model, the assumption of a multivariate normal distribution cannot be satisfied. Consequently, distorted estimates were obtained, and accurate statistical verification was not performed. The skewness and kurtosis of the variables selected for this research model satisfied the conditions necessary for the application of the structural equation model, considering the normal distribution condition (skewness less than 2, kurtosis less than 7) [22] in the structural equation model (Table 2).

Analysis through verification of structural equation model

Analysis of direct effects

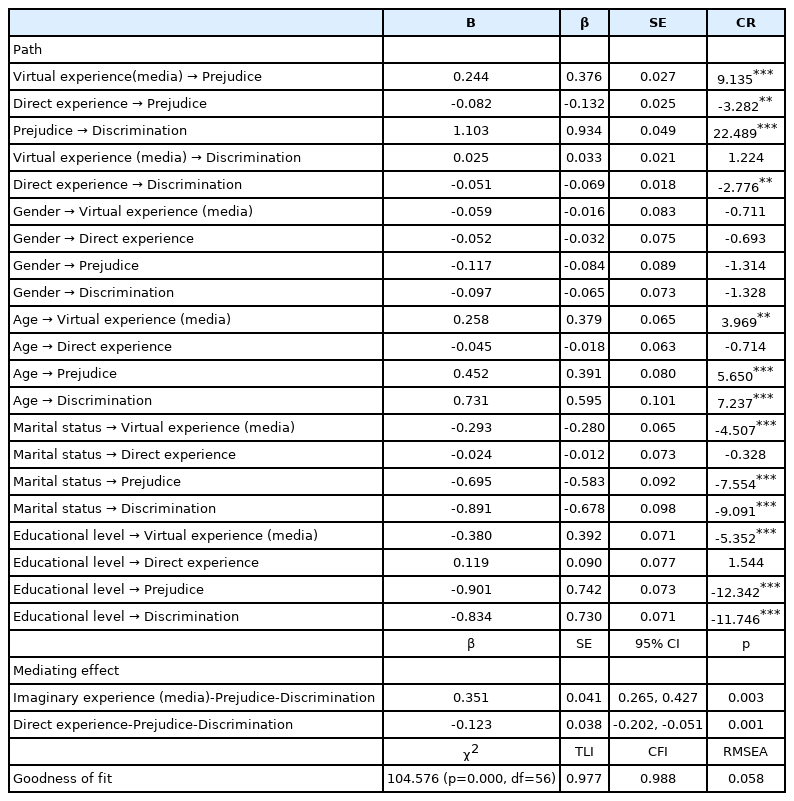

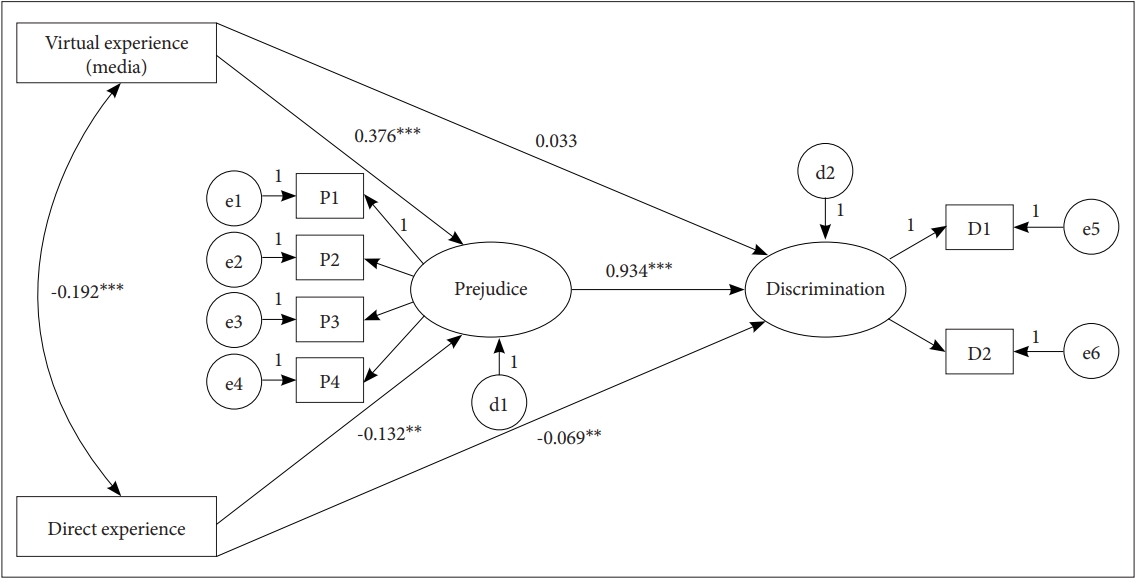

In this study, the goodness-of-fit of the model was verified using CFI, TLI, and RMSEA. None of these factors was sensitive to the sample size. The evaluation criteria for the fit index were established with due consideration to the simplicity of the model [23]. The goodness-of-fit of the research model was found to be satisfactory for all fitness indices except for χ2 (Figure 1, Table 3) [24].

Structural equation model linking virtual experience, direct experience, prejudice (P), and discrimination (D). Research models and estimates on influence relationships between key variables. **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. e, measurement error; d, unexplained error.

The results for the direct effects are as follows. The influence of virtual experience through mass media on prejudice (β=0.376, p<0.001), the influence of direct experience with people with severe mental illness on prejudice (β=-0.132, p<0.01), the influence of prejudice on discriminatory behavior (β=0.934, p<0.001), and the influence of direct experience with people with severe mental illness on discriminatory behavior (β=-0.069, p<0.01) were statistically significant. However, the influence of virtual experience through mass media on discriminatory behavior (β=0.033, p>0.05) was not statistically significant (Table 3). Furthermore, controlling the sociodemographic characteristics of the study subjects showed that these characteristics have a significant effect on the major variables in several pathways (Table 3).

Analysis of indirect effects

The direct effects of each variable are an independent part of the total effect, which does not have a relationship with the other variables in the model. The indirect effects of each variable are part of the total effect mediated by the other variables in the model. The bootstrapping method was used to analyze the significance of mediating effects. In the path of virtual experience through mass media-prejudice-discriminatory behavior, the full mediating effect of prejudice (β=0.351, p=0.003) was found to be statistically significant. In addition, in the path of direct experience with people with severe mental illness-prejudice-discriminatory behavior, the partial mediating effect of prejudice (β=-0.123, p=0.001) was found to be statistically significant (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study carried out a structural model analysis on how prejudice and attitude toward people with severe mental illness that are formed through consuming mass media affect discriminatory behavior towards such patients. It attempted to provide basic data for developing an intervention strategy to reduce prejudice and discriminatory behavior toward people with severe mental illness. Moreover, this study also aimed to prepare a plan to implement a recovery paradigm for mental illness. The main research results are as follows.

First, the results as related to the direct effects of major variables are discussed. This study found that virtual experience through mass media exposure had a statistically significant effect on prejudice against those with severe mental illness. The public developed a prejudicial attitude toward people with severe mental illness as a result of biased media content, viewing them as incompetent, dangerous, and unrecoverable. These results are in line with the results of previous studies that found that the public develops a negative perception of those with severe mental illness owing to unverified media coverage and perceived increased risk to themselves or loved ones [25-27]. Thus, efforts to reduce prejudice against those with mental illness by using the mass media and revising the “mental health media rules” to improve inappropriate and negative media coverage of people with severe mental illness are needed. The Advocates for Public Interest Law (https://swlc.welfare.seoul.kr/swlc/index.action) claimed that the media creates a threatening image of those who have mental illness by using various editing methods such as sound, lighting, wallpaper, and camera angles. They also pointed out that the media focuses on finding dramatic headlines that contain terms such as “murder” and “violence” rather than worrying about whether the contents of the broadcast will cause prejudice against mental illness [28]. In fact, reports claim that the prevalence of murder, arson, and drug-related crimes caused by people with severe mental illness is high. [2,4]. However, the broadcast of and emphasis on only negative and threatening reports of people with severe mental illness may lead to a vicious social cycle wherein hatred toward them and their family among public increases, and as a result, might miss the golden hour to treat them. This has detrimental effects on both the persons suffering from severe mental illness and their caregivers. Therefore, the media needs to exercise caution and broadcast/publish more balanced reports on the quality of life of such people, including their social integration and recovery in the community [29]. Monitoring of mass media that reports on mental illness based on interest rather than accurate knowledge is extremely necessary. This includes coverage of people with severe mental illness that depicts them as inherently violent and dangerous. The media urgently needs a system to be established that allows them to receive feedback from concerned experts when they report stories related to mental illness. This study also showed that direct experience had a positive influence on reducing prejudice and discriminatory behavior. This corresponds with previous research that found that the experience of meeting patients with schizophrenia in person helped overcome prejudice rather than enable it [14-16]. This also corresponds with studies that indicated that personal interactions between ordinary people and the mentally challenged reduced the social distance between them and encouraged a more receptive attitude toward the latter [30,31]. Therefore, it is necessary to formulate and promote various anti-stigmatization programs that provide opportunities for people with severe mental illness and the general population to meet physically while receiving treatment and rehabilitation.

Next, the direct effects of prejudice against those with severe mental illness on discriminatory behavior were found to be significant. These results imply that prejudice toward those with severe mental illness strengthens stigmatization. Indeed, many who are exposed to this rhetoric refuse to form personal relationships with people they perceive to have mental illness and are driven to deprive them of their basic social rights. This supports the results of previous studies that addressed the relationship between prejudice and discriminatory behavior [32,33]. In particular, the link between mental illness and crime increases public fear and promotes prejudice. As a result, the stigma is reinforced, and the basic rights of the person concerned are restricted, denying them protection. Accordingly, the media should refrain from making presumptuous reports of a link between mental illness and crime.

Age, educational level, and marital status were all found to have effects on virtual experience through mass media, prejudice, and discriminatory behavior. These results imply that strategies intended to reduce negative beliefs against people with severe mental illness should target older people, less-educated populations (groups with less than a university degree), and married people. These groups are key to the successful implementation of a mental health promotion strategy, such as awareness improvement education at a metropolitan or basic mental health welfare center. In addition, the “educational program on the prevention, treatment and recovery of mental illness” for the general public needs to be expanded so that knowledge about mental illness can be improved and prejudiced attitudes toward people with severe mental illness can be reduced.

Second, results related to the indirect effects are discussed. The full mediating effect of prejudice was found to be significant for the virtual experience through the mass media-prejudice-discriminatory behavior path. This suggests that discriminatory behavior is not directly expressed under the influence of mass media. Rather, discriminatory behavior is expressed because of prejudice formed by the negative influence of mass media. Additionally, it was noted that the partial mediating effect of prejudice was significant on the direct experience-prejudice-discrimination behavior path. This implies that the level varies depending on the prejudice toward those with severe mental illness, since direct experience reduced the likelihood of discriminatory behavior. Consistent with previous studies that emphasize the importance of direct experience [14-16], the results of this study suggest a need for measures that will reduce prejudice and social distance. These indirect effect results are consistent with the results of previous studies that indicated the severity of prejudice formed through exposure to mass media coverage [7-9]. These results imply the need for measures to reduce prejudice. For this, a strategy of benchmarking research based on the effectiveness of a program or campaign in a developed country in which direct encounters with people with severe mental illness took place will be helpful. An example of an effective campaign is the “Time to Change” campaign launched in the United Kingdom, which uses mass media and promotes encounters between people with severe mental illness and the general public within the community. Another example is the “Crazy? So What!” project conducted in Germany, a program that allowed students to meet with people with schizophrenia [34]. Moreover, efforts to change the perception that emphasizes the paradigm of recovery are needed. The public should be made aware of the fact that social problems related to mental illness are not all crime-related. Indeed, there are many problems related to the scope of community rehabilitation services, economic problems faced by the person and their family, and discrimination and alienation at the national level. Facts about treatment and prevention management, and an understanding that mental illness is a recoverable disease that anyone can get, should be emphasized.

Limitations and conclusion

The limitations of this study and suggestions for future research are as follows. First, in this study, direct effect analysis and mediating effect analysis were carried out by focusing on the influence of mass media, prejudice, and attitude as factors affecting discriminatory behavior toward people with severe mental illness. However, there is a limitation in measuring the influence of mass media with fragmentary items. Thus, it is necessary to expand the types of mass media examined in this study to include social networking sites and analyze their relevance to prejudice or discriminatory behavior in the future. Second, an empirical experimental study needs to be carried out to examine whether there has been any actual reduction of prejudice or discriminatory behavior regarding the effectiveness of the public perception improvement program presented in this study. Despite these limitations, this study is significant in that it provides the theoretical basis for intervention strategies to establish a recovery paradigm.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Sung-Wan Kim and Jong-Woo Paik, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ok Kyung Yang, Sung-Wan Kim, Yu-Ri Lee. Data curation: Jinhee Hyun, KiYeon Lee, Jong-Woo Paik, Yu-Ri Lee. Formal analysis: Yu-Ri Lee. Funding acquisition: Ok Kyung Yang. Investigation: Ok Kyung Yang, Jinhee Hyun. Methodology: Yu-Ri Lee, Sung-Wan Kim. Project administration: Ok Kyung Yang, KiYeon Lee, Yu-Ri Lee. Supervision: Ok Kyung Yang, Jong-Woo Paik. Writing—original draft: Ok Kyung Yang, Sung-Wan Kim, Yu-Ri Lee. Writing—review and editing: Yu-Ri Lee.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea [Grant No.: 11-1620000-000763-01].