Impact of a Psychiatric Consultation Program on COVID-19 Patients: An Experimental Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Following the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak, the importance of addressing acute stress induced by psychological burdens of diseases became apparent. This study attempted to evaluate the effectiveness of a new mode of psychiatric intervention designed to target similar psychological crises.

Methods

Participants included 32 out of 114 COVID inpatients at a hospital in Daegu, Korea, who were assessed between March 30 and April 7, 2020. Multiple scales for screening psychological difficulties such as depressed mood, anxiety, insomnia, acute stress, and suicidality were done. Psychological problem evaluations and interventions were conducted in the form of consultations to alleviate participants’ psychological challenges via telepsychiatry. The interventions’ effects, as well as clinical improvements before and after the intervention, were analyzed.

Results

As a result of screening, 21 patients were experiencing psychological difficulties beyond clinical thresholds after COVID-19 infection (screening positive group). The remaining 11 were screening negative groups. The two groups differed significantly in past psychiatric histories (p=0.034), with the former having a higher number of diagnoses. The effect of the intervention was analyzed, and clinical improvement before and after the intervention was observed. Our intervention was found to be effective in reducing the overall emotional difficulties.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the usefulness of new interventions required in the context of healthcare following the COVID-19 pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

Korea had reported several confirmed coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) cases before the World Health Organization declared the pandemic [1]. Initially, people with an overseas travel history were infected; however, after the 31st confirmed case, the infection rate in Daegu increased exponentially and spread among the community. Pandemics and other similar events can cause psychological challenges in the form of emotional symptoms and aftereffects. In fact, in the early days of the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak, various psychiatric disorders were reported, such as persistent depression, anxiety, panic attacks, psychomotor excitement, psychotic symptoms, delirium, and even suicidality [2,3]. There are many possible causes for this trend. First, infection symptoms or treatments’ side effects can cause emotional problems. A previous study revealed that seropositivity for influenza and coronavirus was associated with a history of mood disorders and suicide attempts [4]. Moreover, anxiety symptoms and distress may be worsened by infection symptoms and medicines’ adverse effects [5]. Second, the mandatory contact tracing and 14-day quarantine could increase patients’ anxiety and guilt about the disease’s effects and the stigma faced by their families and friends who had been infected [6]. Quarantining also reduces avenues for interpersonal communication, leading to the development or exacerbation of depression or anxiety, and creates difficulties in receiving timely psychological interventions or routine counseling [7]. Third, COVID-19 can worsen existing mental illnesses and mental healthcare. The widespread anxiety regarding the pandemic may worsen existing symptoms, and previously available psychiatric treatment could be delayed or become inaccessible owing to quarantine and social blockages. Additionally, previous research suggests that patients with existing psychiatric issues may be more susceptible to the novel coronavirus infection because they may not be promptly and fully aware of the pandemic; they may have difficulties in accepting and cooperating during self-quarantine; and they may lose their sense of self-protection [8]. Fourth, social factors such as social stigma and criticism can contribute to psychological difficulties. In Korea, criticism of certain religions, such as Shincheonji or the New Heaven and New Earth Church, which were the precursors to community spread, can undermine the psychological conditions of their adherents.

Emotional responses can persist as aftereffects even after the disaster situation has passed. A prior study showed that the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increased in survivors of infectious diseases [9]. Serious levels of PTSD symptoms were reported by medical staff and hemodialysis patients who were quarantined during the Middle East respiratory syndrome epidemic, despite the considerable time between quarantine and research [8]. It also increased awareness about the need for emotional support for infected people, isolators, medical personnel, and the general public [9-11]. Therefore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, psychiatric support is essential to prevent the occurrence of psychiatric morbidity and subsequent mental aftereffects, and crisis intervention must be implemented in the early stages to reduce anxiety, depression, and PTSD [8]. Moreover, it is crucial to proceed with these psychological interventions while also blocking the infection spread. Xiang et al. [6] proposed three important components in terms of mental health management in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: 1) multidisciplinary mental health teams, 2) clear communication with regular and accurate updates about the pandemic, and 3) establishment of secure services to provide psychological counseling. We operate the COVID-19 inpatient ward at a hospital in Daegu, Korea, and observed that patients suffered from psychological difficulties ranging from mild insomnia to suicidal ideation. To alleviate their conditions, we implemented a new mode of psychiatric consultation and assessed its effectiveness.

METHODS

Participants

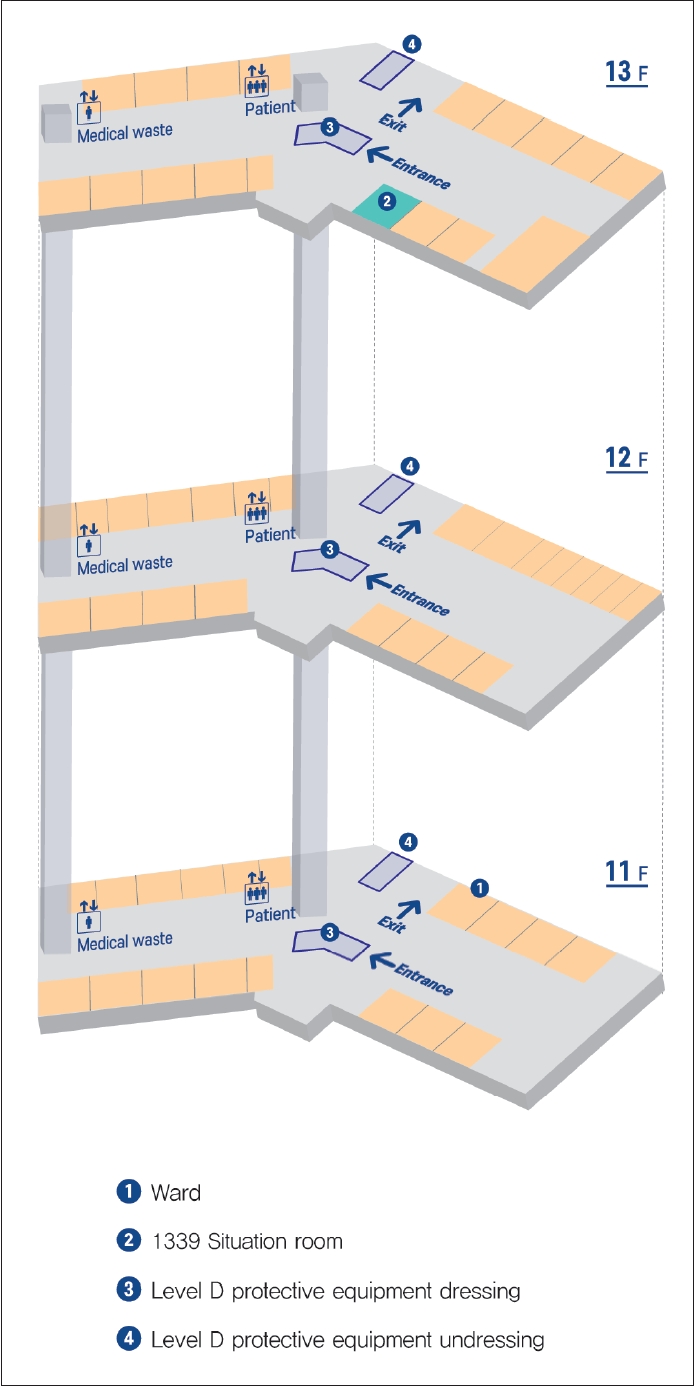

Patients admitted in the COVID-19 inpatient ward of the Catholic University Hospital, Daegu, between March 10 and April 7, 2020, were enrolled in the study. The quarantine ward can accommodate over 100 patients and is designed to meet the community’s medical needs (Figure 1); it also includes bathrooms, internet connection, and patients’ personal electronics. Patients self-reported their vital signs and notified them to the medical staff via phones. The medical team conducted the treatment via phones, and in the event of an emergency, they wore protective clothing for face-to-face treatment. Participants’ hospitalization period was approximately 14 days, and the discharge criteria included testing negative for COVID-19 tests conducted at intervals of 48 hours. Detailed information about the study was provided to all participants and written informed consent was obtained from them. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (DCUMC IRB approval No. CR-20-062) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, 1964).

Procedures

To provide psychological support in the form of a psychiatric consultation program, two trained psychiatrists shared and standardized consulting methods and content, and provided telephone counseling. Assuming that all participants were experiencing acute stress, we included all patients except those who were unconscious, severely ill, or reluctant to participate.

Psychiatric Consultation Program

The program consisted of a first interview, a psychological evaluation, and following psychiatric interviews. A psychiatrist conducted the first telephonic interview, during which future psychiatric interventions were explained to participants. Psychological evaluation was conducted through online surveys via participants’ mobile phones, to assess their condition safely and efficiently. For participants who had difficulty using mobile devices, the researchers read the survey questions over the phone and noted their answers. The basic assessment items were depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, insomnia, and suicidal ideation, chosen based on the common symptoms reported by those who experienced psychological disasters [2,3]. The overall psychopathology was explored to see if any of the assessment items exceeded the cut off score on screening. Psychiatric interviews were also conducted over the telephone to minimize the risk of infection transmission. The intensity and method of interviews differed depending on the severity of participants’ survey scores. We divided the participants into screening positive (SP) and screening negative (SN) groups based on the results of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), Primary Care PTSD Screen for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (PC-PTSD-5), Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS), and P4 suicidality screener. If scores on any of the scales crossed the cut off point, the patients were designated to the SP group; otherwise, they were included in the SN group. If participants were included in the SN group, they were educated about their conditions, and received stress management and relaxation therapy so as to reinforce their healthy coping strategies or reassure them that many resources were available. The average interview time in such cases was 10 to 20 minutes. If participants were included in the SP group, interviews were conducted with an overall mental symptom assessment using the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), and the average interview time was 30 to 40 minutes. In addition, when the participants reported serious suicide/self-harm ideation or attempts, crisis interventions were provided. First, the psychiatrist entered the ward wearing level D protective clothing to interview them directly. During the interview, diagnostic assessment, future disposition plan, and whether medication was needed were determined. Emotional support through statements that illustrate empathy, trust, and care and instrumental support fulfilling practical needs were simultaneously delivered to the patient. Psychiatric interviews were conducted two to three times a week, and the last consultation and psychological evaluation were conducted on the discharge day (Figure 2).

Process of the psychiatric consultation program. CGI, Clinical Global Impression; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7, 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; PC-PTSD-5, Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5; AIS, Athens Insomnia Scale; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; SP, screening positive.

Measurements

Sociodemographic data

Data were collected on the following variables: age, sex, marital status, cohabitation family status, religion, education level, occupation, and type of insurance.

Clinical data

Data were collected on the following variables: quarantine type, quarantine period, infection route, past medical history, past psychiatric history, medication history, infectious disease level (National Early Warning Score [NEWS], presence of pneumonia on chest radiography, and oxygen supply).

NEWS

Determining the degree of illness guides critical care intervention. The NEWS is based on a simple aggregate scoring system in which scores are allocated to physiological measurements and recorded in routine practice. Six simple physiological parameters form the basis of the scoring system: respiration rate, oxygen saturation, systolic blood pressure, pulse rate, level of consciousness or new confusion, and temperature [12,13]. We designated NEWS scores of 1–4 as mild, 5–6 as moderate, and ≥7 as severe.

Assessment of psychological and mental problems

Clinical Global Impression (CGI)

The CGI is a brief clinician-rated instrument that consists of three different global measures [14]. The CGI severity of illness measure (CGI-S) is rated from 1 (normal, not at all ill) to 7 (among the most extremely ill patients); 0 is allocated if the patient was unassessed. It was conducted during admission (CGI-Sadm) and discharge (CGI-Sdis). The CGI global improvement measure (CGI-I) is rated from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse); 0 stands for “unassessed.” It was rated at discharge only.

Depressive symptoms

The Korean version of the PHQ-9 was used to screen depression. PHQ-9 evaluates the severity of the symptoms by summing all items’ scores [15]. The total score ranges from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicative of higher depression severity. This study used the PHQ-9 scale translated into Korean by Han et al. [16], with a cutoff score of 6 points for depression [17].

Anxiety

Anxiety was measured using the GAD-7 [18]. It is self-reported on a 4-point Likert scale. The total score ranges from 0 to 21, with scores of 5–9 as mild, 10–14 as moderate, and ≥15 as severe. We used a cutoff score of 5.

Post-traumatic stress symptom

PC-PTSD is used for trauma assessment in psychological disaster situations owing to its high level of diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility [19,20]. It consists of five questions that reflect the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition diagnostic criteria, each answered with a “yes” or “no.” It was first translated into Korean (K-PC-PTSD-5) by Jung et al. [21], and showed high psychometric properties. Its optimal cutoff score is 3 [22].

Insomnia

To measure sleep conditions, we used the AIS developed by Soldatos et al. [23]. It consists of eight questions and has proven validity and reliability in the diagnosis of sleep-related problems and insomnia. A 4-point Likert scale was used, with the scores ranging from 0 to 24 points. A total score of more than 6 was determined as clinical insomnia [23].

Suicidality

P4 Suicidality Screener is a simple screening tool for assessing suicide risk [24]. It starts with the question “Have you had thoughts of actually hurting yourself?”; if responded with “yes,” additional four screening questions are asked, namely, past suicide attempt, a suicide plan, probability of completing suicide, and preventive factors. Based on the answers, suicide risk is rated as minimal, low, and high. In this study, patients responding with “yes” to the first question were screened as positive for suicidality.

SCL-90-R

SCL-90-R is a widely used questionnaire to determine several psychological symptoms [25,26]. It includes 90 symptoms and evaluates nine symptomatic dimensions: somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. Participants were instructed to select scores corresponding to symptom prevalence over the previous seven days, including the test day, using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often). In Korea, Kim et al. [27] standardized the questionnaire in 1984.

Statistical Analysis

Independent-samples t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test were used to compare sociodemographic or clinical characteristics depending on whether the subjects were screened positive. Paired samples t-test for parametric data or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-parametric data were performed to compare changes within participants before and after the program. We used IBM SPSS version 25.0 for data analyses (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

RESULTS

Participants

During the intervention period, 114 (39 men, 75 women, and 58.82±19.66 years old) patients were admitted to the COVID-19 inpatient ward. Among them, 73 subjects were excluded; the exclusion criteria included cases with serious physical or neurological conditions at the time of treatment (n=62), brain damage or concussion accompanied by unconsciousness (n=10), and difficulty in understanding psychological interventions due to apparent deterioration of cognitive ability at the time of care (n=1). Cases where additional interviews were denied post the initial one, or appropriate data were not obtained due to insincere responses or unexpected early discharges, were also excluded (n=9). Finally, 32 subjects were included in the analyses (Figure 3).

Sociodemographic and clinical data

The overall sociodemographic data of the participants are presented in Table 1. More than half were aged >40 years (range=50.56±17.42 years). There were more women (n=20, 62%) than men (n=12, 38%), and more than half were married (n=19, 59%). Most followed a religion (n=28, 87%), of which Christianity and New Heaven and New Earth accounted for 28%, respectively. Seventy-five percent had at least a middle school education (n=24), were employed (n=24), and 66% were covered by health insurance (n=21). In most cases, multi-person rooms (n=28, 87%) were used and the quarantine period at the time of assessment was 1–3 weeks (n=29, 91%). Infection pathways varied and were most often unknown (n=13, 41%). A total of 56% (n=18) had past medical histories, and 37% (n=12) had past psychiatric histories. In terms of internal conditions, most cases were classified as mild under NEWS (n= 28, 88%). Many cases of pneumonia (n=24, 75%) were detected on x-rays and chest-computed tomographys; however, in most cases (n=28, 87%), no oxygen supply was required. All 32 subjects took internal medication (e.g., antiviral drugs, Kaletra, antibiotics, hydroxychloroquin) owing to COVID-19.

In the SP group (n=21) (5 men, 16 women, and 55.43±16.52 years old), most participants were in their 40s or older (n=18, 86%), the proportion of women (n=16, 76%) was similar to that in the total subjects, and the proportion of elderly patients in their 60s and above was higher. Sociodemographic factors, quarantine type, and medical conditions also showed similar tendencies. However, more than half (n=11, 52%) had past psychiatric histories. In the SN group (n=11) (7 men, 4 women, and 41.27±15.84 years old), most participants were in their 20s (n=4, 36%), with twice as many men as women. In terms of religion, New Heaven and Earth (n=4, 36%) had the highest number of followers, but had either mild medical histories or no medical or psychiatric histories.

Clinical changes before and after the program

Intervention effects were analyzed by comparing the sum of the pre- and post-tests, the number of tests corresponding to screening positives, CGI, and SCL-90-R results (Table 2). For all the participants, PC-PTSD-5 (p=0.041) and CGI-S (p<0.001) demonstrated statistically significant improvements. The mean CGI-I was 3.25±0.92. For the SP group, the number of scales which crossed the cutoff point (p=0.022) and CGI-S (p=0.001) displayed statistically significant improvements; the mean CGI-I was 3.00±1.00. Further, for this group, in-depth evaluation using SCL-90-R and more intensive intervention were conducted. Global Severity Index (GSI) (p= 0.026), Positive Symptom Distress Index (PSDI) (p=0.046), and Depression (p=0.042) demonstrated statistically significant improvements. The SN group showed no significant differences in the pre-post evaluation (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The novelty and contribution of this study lie in its socioenvironmental context: it focused on an intervention delivered directly by psychiatrists in a hospital setting in an area with a large-scale community outbreak of COVID-19. Based on the results, patients in the COVID-19 ward mostly comprised women in their 60s and older. Among them, many who received psychological support had mild medical conditions; for instance, even if pneumonia was detected, supportive oxygen was rarely needed. This was due to the exclusion of patients with severe physical or neurological conditions. The SP group included older women, whereas the SN group comprised a relatively younger male population. However, no statistically significant differences were found among the two groups in terms of sociodemographic variables, quarantine histories, and severity of medical conditions. However, the SP group had a higher frequency for psychiatric histories (p= 0.034). A review of the results of additional questions was conducted to assess the possibility of deterioration of underlying symptoms due to decreased access to psychiatric treatment during quarantine. A total of 12 participants reported previous psychiatric history, which largely comprised depression (n=5, 16.1%) and anxiety (n=3, 9.7%), while others had sleep disorders, alcohol use disorders, and other mental disorders. Approximately 50% were on medication for psychiatric treatment immediately before the COVID-19 outbreak; but all of them had maintained themselves during quarantine. In the COVID-19 era, it is assumed that individuals with psychiatric histories may be more vulnerable to emotional stress, as opposed to the deterioration of psychiatric symptoms due to limited therapeutic accessibility. This trend has also been shown in several relevant studies: patients with a severe mental illness had only slightly higher risks for severe clinical outcomes of COVID-19, than patients without psychiatric histories [28,29]. Patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and who had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder had a 1.5-fold increased risk of COVID-related death, in comparison with COVID-19 patients who had not received a psychiatric diagnosis [30]. The authors attributed this result to the potentially inflammatory factors and stress responses that the body experiences in consideration of prior psychiatric conditions, existing neurochemical differences, and vulnerability to respond to an acute stressor such as COVID-19 [30]. In fact, a fifth of Australian soldiers dispatched to Somalia had psychiatric morbidity after 15 years, with risk factors for its occurrence being combat exposure and past psychiatric history [31]. In another study, survivors of a devastating earthquake were tracked three years later, and were diagnosed with PTSD and major depressive disorder simultaneously if they had histories of psychiatric disorders and traumatic experiences.32 Hence, psychiatric histories can affect emotional difficulties in stressful situations independent of current symptoms or treatments, which may be further influenced by factors such as individual ability to adapt to stress, ability to deal with emotional difficulties, and genetic vulnerabilities.

In terms of the effect of the psychiatric intervention, all participants from the SP group showed significant clinical improvements, but none from the SN group demonstrated any significant changes. However, all participants reported statistically significant reductions in the sum of the PC-PTSD-5; the SP group showed a significant reduction in positive scores and scores from the SCL-90-R in GSI, PSDI, and depression scale. The CGI-S pre- and post-assessment scores for all participants ranged from 2.25 to 1.53, meaning that, on average, participants went from “borderline mentally ill” to “normal, not at all ill.” The mean CGI-I value was 3.25, which is equivalent to “minimally improved.” The pre- and post- CGI-S value in the SP group was 2.71 and 1.76, respectively, indicating that, on average, there was a decrease to “mildly ill” from “borderline mentally ill.” The mean CGI-I value in the SP group was 3.00, corresponding to “minimally improved.” For the SN group, the pre- and post- CGI-S values were 1.36 and 1.09, respectively, which did not differ significantly.

Overall, the PC-PTSD-5 decline is believed to be based on the adaptations needed to reduce immediate acute stress. The program was effective in improving participants’ normal adaptation response to acute stress and preventing them from experiencing chronic aftereffects. An example of this acute intervention is psychological first aid (PFA) [33]. It is a globally implemented approach to help people affected by an emergency, disaster, or other adverse events, designed to reduce the initial distress and foster short- and long-term adaptive functioning and coping [34]. Many traumas hence do not escalate to PTSD, empowered by individuals’ natural resiliency. Such findings are embedded in the concept of PFA, which has eight core components: contact and engagement, safety and comfort, stabilization, information gathering, practical assistance, connection with social support systems, coping information, and linkage with collaborative services [35]. The goal is to inform survivors of the services available to them. Our intervention also has all eight core components, with particular emphasis on stabilization and coping information. It can be interpreted as having effects similar to those of the PFA.

For the SP group, which displayed high levels of psychological difficulties, there was a clinical need to target relatively diverse illnesses such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia; however, the number of screening positives decreased after the intervention. This means that experiences of more severe symptoms of certain illnesses were reduced, which is also supported by the GSI reduction in SCL-90-R. Essentially, this primary intervention reduced the severity of clinical problems, while simultaneously reducing stress (as implied by the change in SCL-90-R PSDI value). The PSDI is a measure of participants’ response styles, reflecting overestimation or underestimation of symptoms [36]. Acute adversities distort individuals’ perception, but our intervention improved their perception and sense of self-efficacy.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, interviews and evaluations with psychiatrists were largely conducted without face-to-face contact to prevent the risk of infection. This limits the practice of using tools that allow doctors to observe and evaluate patients directly. Further, the effectivity of nonpersonal/non-contact interviews for forming therapeutic alliances (as compared to conventional interview techniques) is yet to be determined [37]. However, based on a prior study, telepsychiatry was found to be feasible in a wide range of settings, across psychiatric treatments, in different ethnic groups and populations, and all age groups [38,39]. An increasing number of controlled trials are demonstrating its effectiveness in specific treatments and exploring wider benefits, such as cost savings associated with reduced travel, improved care coordination, and cost avoidance through early treatment [40-42]. Previous work has specifically described the potential for using telemedicine in disasters and public health emergencies [43,44]. In other words, it is a useful method worthy of further evaluation, especially as the risk of infection continues to increase. In this regard, our research is valuable as it provides the basis for telephonic psychiatric consultation and proves its utility in disaster situations. Additionally, some of the aforementioned limitations can be overcome if applications that allow video meetings are used.

Secondly, there may be a possibility of selection bias, as the study was conducted with inpatient ward patients of the hospital. Not all confirmed cases are admitted to hospitals, and in the case of usual or minor symptoms, many self-quarantine in their homes or community centers. According to data released in April 2020 by the Korean government, the confirmed cases were 69.6% of the total in their 20s to 50s. In particular, 27.4% in their 20s showed a higher percentage than other age groups [45]. However, in our study, people in their 60s and older accounted for the largest percentage; hence our finding that 66% of participants reported experiencing emotional difficulties may be an overestimation due to participants’ ages. If this program is performed at various agencies in the region, we believe that the impact of these selection biases will be reduced. Despite the above limitations, this study suggests an approach to psychiatric intervention while following safety rules during the pandemic, and promotes healthy adaptation reactions in stressful situations to reduce mental symptom severity and resultant stress. Moreover, since most of the studies conducted during the COVID-19 outbreak have been observational, it is notable that this study conducted direct psychiatric interventions, and that the emerging treatment pathway of teleconsultation has been introduced and assessed for effectiveness.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Daegu Catholic University Hospital but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Geun Hui Won, Tae Young Choi. Data curation: Hye Jeong Lee, Jong Hun Lee, Hyo-Lim Hong, Chi Young Jung. Formal analysis: Geun Hui Won, Hye Jeong Lee. Funding acquisition: Tae Young Choi. Investigation: Jong Hun Lee, Hyo-Lim Hong, Chi Young Jung. Methodology: Geun Hui Won, Jong Hun Lee, Tae Young Choi. Supervision: Jong Hun Lee, Tae Young Choi. Writing—original draft: Geun Hui Won, Hye Jeong Lee. Writing—review & editing: Geun Hui Won, Tae Young Choi, Hyo-Lim Hong, Chi Young Jung.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by a research grant from Daegu Medical Association COVID-19 scientific committee.