Impact of Resilience and Viral Anxiety on Psychological Well-Being, Intrinsic Motivation, and Academic Stress in Medical Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Article information

Abstract

Objective

We aimed to explore the association between academic stress or motivation and the psychological well-being of medical students during the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. We also explored the effects of their resilience or viral anxiety on this association.

Methods

This online surveyed for medical students was done during October 20–28, 2021. Participants’ age, sex, grades, and COVID-19-related experiences were collected. Their symptoms were measured with Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-6 items, Medical Stress Scale (MSS), intrinsic motivation using Academic Motivation Scale, Connor Davidson Resilience Scale-2 items (CD-RISC2), the 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5), and GRIT scale.

Results

Among 251 medical students, linear regression performed to explore the predicting factors for psychological well-being or medical stress showed that WHO-5 score was predicted by age (β=0.16, p=0.02) and CD-RISC2 (β=0.29, p<0.001) (F=15.5, p<0.001). In addition, the MSS score was predicted by age (β=0.20, p=0.004), intrinsic motivation (β=-0.31, p<0.001), GRIT (β=0.21, p=0.003), and CD-RISC2 (β=-0.31, p<0.001) (F=15.6, p<0.001). The resilience of medical students partially influenced their intrinsic motivation, affecting their psychological well-being or academic stress. However, no significant association was observed in the case of viral anxiety as a mediator, indicating that viral anxiety did not mediate the association.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of resilience in mediating the relationship between intrinsic motivation and psychological well-being or academic stress. However, viral anxiety was not found to be a mediator in this relationship.

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is caused by a novel type of coronavirus and was first reported in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, in November 2019 [1]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, students could not go to school because of the social distancing policy, and most of the classes were replaced by online lectures including Massive Open Online Course [2]. In 2021, the “With Corona” policy was implemented, partially encouraging students to attend school [3].

In general, medical students are under considerable stress owing to academic burden [4]. Hence, they experience deteriorating mental health, lower psychological well-being, and higher depression than students who are not majoring in medicine [5,6]. Ahn et al. [7] demonstrated that the stress and academic motivation perceived by medical students can have an impact on their academic performance and psychological well-being. During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical students experienced psychological distress. Although they are not healthcare workers, they played the healthcare worker’s role in some cases [8]. Hence, despite not being fully prepared, they served as frontline medical personnel. In addition, during their medical clerkship, they were often near healthcare facilities and faced a great possibility of contracting the disease from patients with COVID-19. Online classes also resulted in psychological distress in medical students owing to their nonfamiliarity with the online teaching system.

Furthermore, during the COVID-19 pandemic, psychological distress was associated with low academic motivation and social disengagement [9]. Although the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted medical students’ education, higher academic, intrinsic, and extrinsic motivations were observed in students who received flipped and jigsaw methods than those who received online education only [10]. Another study showed that students in medical school had higher motivation when online and offline learning were combined, and a sense of belonging mediated this process [11]. Hence, transferring education to the online e-learning system might reduce students’ motivation for studies.

Resilience is defined by the American Psychological Association as the ability to adapt to difficult conditions, such as adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant stress. It has been shown that medical students with higher resilience levels tend to have a better overall quality of life and perception of the educational environment. In addition, a positive relationship has been demonstrated between resilience and academic stress in medical students. Furthermore, Yoo and Park [12] found that academic stress was indirectly influenced by egoresilience, and van der Merwe et al. [13] showed that academic stress was associated with low resilience scores.

In a survey conducted in the German population, a significantly higher anxiety, depression, psychological stress, and COVID-19-related fear was observed than that in the time before the COVID-19 pandemic [14]. In addition, high general anxiety and virus-related anxiety symptoms were also observed in healthcare workers [15]. Medical students in Korea have shown virus-related anxiety when they encountered patients with COVID-19. In addition, COVID-19 outbreak-related lifestyle changes also led to stress in medical students [16]. Egyptian medical students also showed high depression, anxiety, and stress during the COVID-19 pandemic [17]. Furthermore, a high prevalence of sleep and mental health disorders was observed among medical students in Greece owing to the COVID-19 pandemic [18].

Resilience plays a protective role against depression, anxiety, and psychological stress [19]. According to Lin et al. [20], resilience allowed medical students with a buffering capacity in the face of physical demand and quality of life during their clerkship. Yu and Chae [21] also confirmed that the psychological well-being of medical students had a negative correlation with academic burnout but had a positive connection with resilience. Similarly, positive attributes of resilience on life satisfaction were confirmed in a study conducted among Chinese medical students [22].

This study aimed to explore the association between academic stress or motivation and the psychological well-being of medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. We also explored the effects of their resilience or viral anxiety on this association. We hypothesized that academic stress and academic motivation are associated negatively and positively with the psychological well-being of medical students, respectively. We also hypothesized that resilience and viral anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic mediate these associations.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

This study surveyed medical students at the University of Ulsan College of Medicine on October 20–28, 2021. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. The survey form included questions on participants’ age, sex, grades, and COVID-19-related experiences, such as “Did you experience being quarantined due to infection with COVID-19?,” “Did you experience being infected with COVID-19?,” or “Did you get vaccinated?” Past psychiatric history or current psychiatric distress was evaluated by asking “Did you experience or receive treatment for depression, anxiety, or insomnia?” or “Now, do you think you are depressed or anxious or do you need help for your mood state?” The survey forms were prepared using the Google Form service according to the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet e-Surveys guidelines [23]. The usability and technical functionality of this e-survey form were tested by investigators (JH and MP) before implementation. The sample size was estimated based on the number of medical students at the University of Ulsan College of Medicine. Of 251 students, 162 students (64.5%) responded to this survey. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Asan Medical Center (2021-1438), and the requirement of obtaining written informed consent was waived by the IRB.

Measures

Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-6 items

The Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-6 items (SAVE-6) is a validated rating scale developed to measure anxiety responses to viral epidemics [24] and is derived from the SAVE-9 scale [25]. It consists of 6 items, each rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (always). A higher total score indicates a greater degree of anxiety in response to viral epidemics. In this study, we used the Korean version of SAVE-6 and found a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.782 in the sample.

Medical Stress Scale

The Medical Stress Scale (MSS) is a self-rating questionnaire for measuring the stress of medical students [26]. This scale focuses on 5 areas: school curriculum and environment, personal competence/endurance, social/recreational life, financial situation, and future aspirations. Each MSS item can be rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” A higher total score reflects higher levels of stress in medical students. In this study, we applied the 9-item Korean version of MSS [7], and Cronbach’s alpha among this sample was 0.802.

Intrinsic motivation using Academic Motivation Scale

The Academic Motivation Scale (AMS) is a self-rating questionnaire that can measure academic motivation [27], including all 3 subcategories: intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation based on self-determination theory [28]. We applied all 12 items of intrinsic motivation (4 items each of intrinsic motivation to know, to accomplish things, and to experience stimulation). All 12 items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale. In this study, the Korean version of the AMS was used [7], and Cronbach’s alpha of 12 items of intrinsic motivation was 0.872 in the sample.

Connor Davidson Resilience Scale-2 items

The Connor Davidson Resilience Scale-2 items (CD-RISC2) is a self-rating scale that can measure resilience. It is a short version of the original full 25-item CD-RISC [29]. Two items can be rated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true nearly all the time). In this study, we obtained permission to use the Korean version of the CD-RISC2 from the original developer (Dr. J. Davidson).

The 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index

The 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) is a self-report questionnaire that can measure the subjective psychological well-being of individuals. It consists of 5 items that can be rated on the Likert scale ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 5 (all the time). The final score is calculated by multiplying 4 the raw total score [30], and a higher score reflects greater psychological well-being. In this study, the Korean version of the WHO-5 [31] was applied, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.782 in the sample.

GRIT scale

Grit is a term conceptualized by American psychologist Angela Duckworth. It refers to determination or courage that plays a decisive role in eliciting success and achievement [32]. In other words, it is a concept that emphasizes the power of effort rather than talent. The short grit scale (GRIT-S) is an 8-item version of the original full 12-item grit scale used to assess the grit of individuals. The GRIT-S was clustered into the following two factors: 1) perseverance of effort (PE) and 2) consistency of interests (CI). Each item can be scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1=not like me at all to 5=very much like me). The total score is divided by 8 and interpreted. The maximum and minimum scores on this scale are 5 (extremely gritty) and 1 (not at all gritty), respectively. A validated Korean version of GRIT-S was used [33], and Cronbach’s alpha for PE and CI categories was 0.820 and 0.759, respectively, in the sample.

Statistical analysis

Demographic variables and total scores of rating scales are presented as mean±standard deviation. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed p-value of <0.05. Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between age and rating scale scores. Linear regression analysis with enter methods was used to identify the variables that predict psychological well-being and academic stress among medical students. Mediation analysis was done to explore whether medical students’ resilience or viral anxiety may mediate the influence of intrinsic motivation on psychological well-being and academic stress by using the bootstrap method with 2,000 resamples. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 21.0, AMOS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and jamovi ver 1.6.18.0 (https://www.jamovi.org).

RESULTS

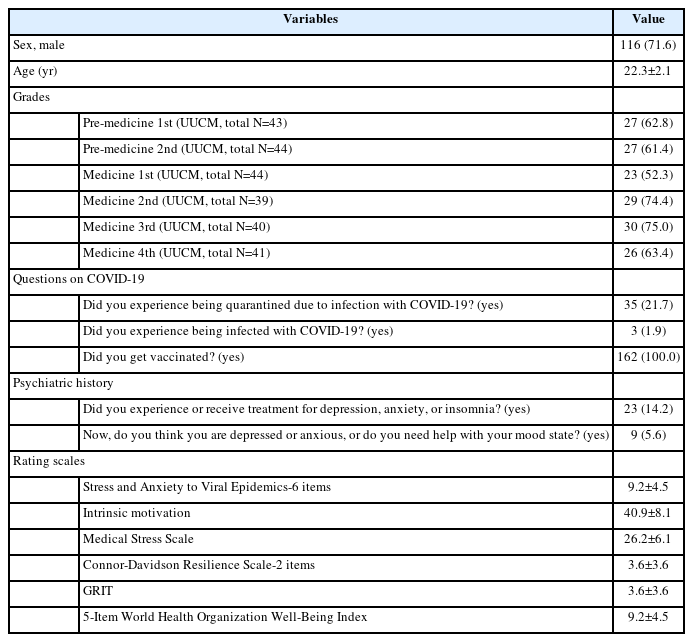

Of 251 medical students of the University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 162 (64.5%) participated in this study (Table 1); 116 (71.6%) were male, 35 (21.7%) experienced being quarantined, 3 (1.9%) experienced being infected, and all were vaccinated.

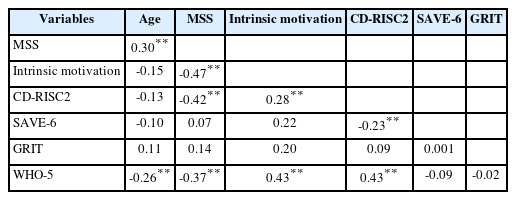

Table 2 shows the results of Pearson’s correlation analysis. Age was significantly and positively correlated with MSS (r=0.30, p<0.01) and significantly and negatively with WHO-5 (r=-0.26, p<0.01). The MSS score was negatively correlated with intrinsic motivation (r=-0.47, p<0.01), CD-RISC2 (r=-0.42, p<0.01), and WHO-5 (r=-0.37, p<0.01). Intrinsic motivation was significantly correlated with CD-RISC2 (r=0.28, p<0.01) and WHO-5 (r=0.43, p<0.01). CD-RISC2 was negatively correlated with SAVE-6 (r=-0.23, p<0.01) and positively correlated with WHO-5 (r=0.43, p<0.01).

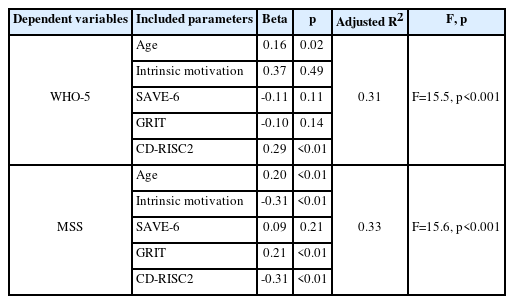

Linear regression analysis was performed to explore the predicting factors for psychological well-being or medical stress (Table 3). WHO-5 score was predicted by age (β=0.16, p=0.02) and CD-RISC2 (β=0.29, p<0.001) (F=15.5, p<0.001). In addition, the MSS score was predicted by age (β=0.20, p=0.004), intrinsic motivation (β=-0.31, p<0.001), GRIT (β=0.21, p=0.003), and CD-RISC2 (β=-0.31 p<0.001) (F=15.6, p<0.001).

Linear regression analysis expecting psychological well-being and academic stress among medical students

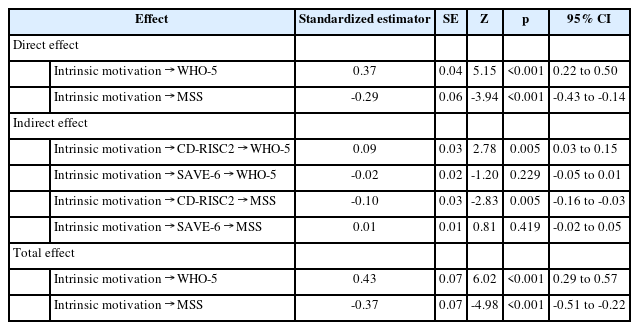

A significant association of intrinsic motivation (independent variable) to resilience (mediator) to psychological wellbeing or academic stress (dependent variable) (Table 4) was observed, indicating that the resilience of medical students partially influenced their intrinsic motivation, affecting their psychological well-being or academic stress. However, no significant association was observed in the case of viral anxiety as a mediator, indicating that viral anxiety did not mediate this association (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

We observed that medical students’ psychological well-being was predicted by age and a high level of resilience, and academic stress of medical students was predicted by age and a low level of intrinsic motivation and resilience or a high level of grit. Students’ intrinsic motivation directly influenced their psychological well-being positively and academic stress negatively. Resilience of medical students partially mediated the influence of intrinsic motivation on their psychological wellbeing or academic stress. However, their viral anxiety did not mediate this association.

Intrinsic motivation, academic stress, and psychological well-being of medical students

According to our study, medical students’ psychological well-being was negatively related to age. Although the study that showed a relationship between psychological well-being and age in medical students was rare, several studies targeted nursing students. Interestingly, similar to the present study, those studies found that the students’ psychological well-being was negatively associated with higher age. Ríos-Risquez et al. [34] found that the older the participants, the worse their perceived psychological health, and He et al. [35] showed that older students had weaker abilities to manage their lives and maintain quality relationships.

Conversely, medical students’ psychological well-being was positively related to resilience. Many previous studies showed the relationship between psychological well-being and resilience. A systematic review [36] revealed that resilience works as a predictor of psychological well-being in nursing students, and similar results were found in other studies [37] targeting medical students. The results obtained in the present study were consistent with those of previous studies.

Our study proved that high level of academic stress in medical students is associated with higher age, higher grit scale scores, lower resilience, and lower intrinsic motivation. Interestingly, medical students who had higher grit scale scores were found to have more academic stress. Grit scale score, which is a concept that emphasizes effort rather than talent in eliciting success and achievement, is calculated using two factors: PE and CI. Students who work hard with perseverance and consistently have an interest in a particular field will have higher grit scale scores, and in the present study, it was found that such students were under more academic stress at baseline while continuing to work hard. Many previous studies [38,39] have shown that people with high grit scale scores have the power to overcome stress and burnout, but ironically, from a different perspective, it is thought that such students usually live under more academic stress.

Mediation effect of resilience or viral anxiety

We found that medical students’ resilience mediated the influence of intrinsic motivation on psychological well-being and academic stress. Several previous studies have shown the mediating effect of resilience on the relationship among various life-related factors of medical students. In a study performed in Korea, resilience was revealed to mediate the relationship between academic burnout and the psychological well-being of medical students [21]. Furthermore, a study of Chinese medical students showed the relationship between academic burnout and life satisfaction, and resilience mediated this relationship [40]. Another study proved that resilience mediates the effect of stress on life satisfaction [22].

In the present study, we could not observe the mediating effect of viral anxiety on the influence of intrinsic motivation on psychological well-being and academic stress. The SAVE-6 score in this study was not significantly correlated with the intrinsic motivation score and MSS score. We speculated that viral anxiety decreases the intrinsic motivation of medical students, since fear of infection and uncertainty about the future may also lead to a decrease in focus and concentration, making it more difficult to sustain motivation for studying. Furthermore, the clerkship of medical students may be related to viral anxiety, as it may involve exposure to a high-risk environment and risk of infection. However, in the present study, it was found that their motivation for studies may not be directly related to viral anxiety. By contrast, medical students may already have adapted to the reality of the pandemic and its potential impact on their lives, explaining the no significant correlation between viral anxiety and academic motivation observed in the present study. It is also possible that the rigorous training and discipline required to become a medical professional may have helped the medical students to develop coping mechanisms and resilience that allow them to manage their viral anxiety and focus on their studies.

This study had a few limitations. First, this study was based on a cross-sectional design; hence, causal effects cannot be inferred. Second, the results may not apply to other populations of medical students since we collected samples from one medical school. Third, self-report measures were used to assess psychological well-being, academic stress, intrinsic motivation, resilience, and viral anxiety; hence, the results may be subject to bias. Finally, this study did not capture the longterm effect of intrinsic motivation, viral anxiety, and resilience on the psychological well-being and academic stress of medical students. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the trajectory of the psychological well-being and academic stress of medical students over time.

In conclusion, this study provides insight into the factors that predict psychological well-being and academic stress among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Age, intrinsic motivation, resilience, and grit were found to be important predictors of psychological well-being and academic stress. Medical students with high levels of resilience and intrinsic motivation were found to have better psychological well-being and lower levels of academic stress. Additionally, this study highlights the importance of resilience in mediating the relationship between intrinsic motivation and psychological well-being or academic stress. However, viral anxiety was not found to be a mediator in this relationship. The results of this study can be used to develop interventions that promote resilience and intrinsic motivation among medical students to improve their psychological well-being and reduce academic stress.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Seockhoon Chung, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Jangho Park, Seockhoon Chung. Data curation: Mingeol Park, Jihoon Hong. Formal analysis: Mingeol Park, Seockhoon Chung. Investigation: Seockhoon Chung. Methodology: Jangho Park, Seockhoon Chung. Project administration: Mingeol Park, Jihoon Hong. Writing—original draft: Mingeol Park, Jihoon Hong. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

None