Development of Mental Healthcare Model in Seoul

Article information

Abstract

Objective

To develop an integrated and comprehensive community-based mental healthcare model, opinions were collected on various issues from practitioners in mental health service institutions currently offering mental healthcare services in Seoul through a focus group interview, qualitative research method, and Delphi survey.

Methods

The focus group interview was conducted with six practitioners from mental health welfare centers and six hospital-based psychiatrists. A questionnaire of opinions on the mental healthcare model was filled by these practitioners and psychiatrists. A Delphi survey was additionally conducted with a panel of 20 experts from a community mental health welfare center and hospital-based psychiatrists.

Results

The focus group interview results showed the need for integrated community-based mental healthcare service and the need to establish a system for managing mental and physical health in an integrated manner. Based on the survey results, the current status of community-based mental healthcare services was investigated, and the direction of the revised model was established. The Delphi survey was then conducted to refine the revised model.

Conclusion

The present study presents the Seoul-type community-based mental healthcare model with integrated services between a psychiatric hospital with a mental health welfare center as well as combined mental and physical health services. This is ultimately expected to help people with mental illnesses live healthy lives by meeting their needs as community members.

INTRODUCTION

Mental illness is a condition that imposes considerable medical, economic, and social burden and presently accounts for about 15% of the total disease burden. Currently, mental health services are not fully integrated despite the importance of continuity in mental healthcare, because of which about 110,000 severely mentally ill patients begin their first treatment each year with worsening symptoms [1]. The majority of mentally ill patients in South Korea (up to 85.5%) are found to have one or more chronic diseases and mental illnesses at the same time, and such complex psychiatric conditions often have negative medical consequences, such as low treatment participation, treatment disobedience, and high readmission rates [2].

The mental health services currently available in Seoul include a mental health welfare center, a suicide prevention center, mental care facilities, mental rehabilitation facilities, an integrated addiction management support center, and medical institutions. Case management of most of the severely mentally ill patients is performed by the Basic Mental Health Welfare Center. According to the 2019 National Mental Health Status Report [3], the number of severely mentally ill patients was estimated to be 97,291. In contrast, the number of members registered at the mental health welfare center was only 9,950, meaning that less than 10% of patients were registered and receiving services. This shows that the majority of patients in need of help are not receiving community care and that the center is having difficulty finding such subjects.

The number of professional agents in charge of case management in Seoul was 246 in 2019, and the number of registered members was 9,950, so the number of cases per professional agent was about 40 [3]. To solve this problem, the local government of Seoul has implemented the Seoul-type intensive case service since 2017 that limits the number of people subject to intensive case service per professional agent to five [4]. Although, the community life maintenance rate has improved and hospitalization rate has decreased in the case of those receiving intensive case management services [4], because of the limited availability of resources, it is inevitable that the service provision has diminished for those who are not candidates for intensive case management services.

Despite the importance of continuity of the delivery system in mental healthcare, the current mental health service availability in Seoul is fragmented. Community services for mentally ill patients are primarily centered on case management, but the health and welfare as well as mental health and physical care providers vary and are provided in segments. Currently, the Mental Health and Welfare Act is based on the sending a fact notice such as discharge; however, it is not effective because the consent rate is low, and consent is often withdrawn later. In addition, most of the local workers at the center are social welfare workers and not psychiatrists, so the supervision for medical services is very limited.

To develop an integrated and comprehensive community-centered mental healthcare model, in-depth discussions on the current mental health service delivery system, service providers and manpower, service content, and boundaries between the service delivery systems are needed. In this study, we propose the modified Seoul-type mental healthcare model comprising mental and physical healthcare services; this model integrates a segmented service provision system through connections between medical institutions and the community mental rehabilitation system.

Thus, this study attempted to collect opinions on various issues from practitioners in mental health service institutions currently offering mental healthcare services in Seoul through a focused group interview (FGI) and the qualitative research method. Moreover, based on the results of the study, the qualitative aspects of the community-centered mental healthcare service are intended to be improved through the proposed Seoul-type mental healthcare model. This is expected to enable community-based mental healthcare services to function efficiently in helping patients live healthy lives through a comprehensive healthcare program.

METHODS

The study was designed to identify the current status and future directions of community-based mental healthcare services through a FGI conducted with a group comprising hospital-based psychiatrists and manager-level practitioners at mental health welfare centers. The following questionnaire of opinions on the revised mental healthcare model was filled by these psychiatrists and practitioners. After deriving the Seoul mental healthcare model based on the FGI and expert survey results, a Delphi investigation was conducted to diagnose the model feasibility and effectiveness.

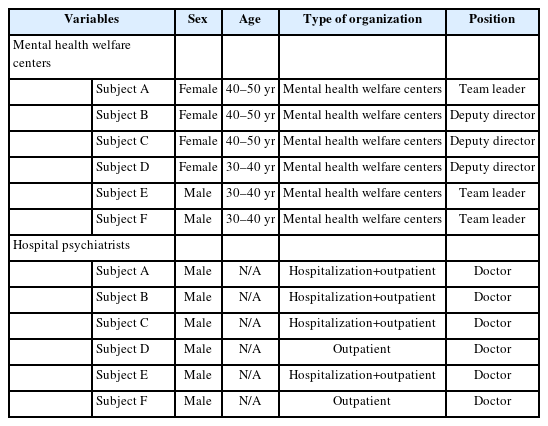

The FGI panel comprised six manager-level practitioners at mental health welfare centers and six hospital-based psychiatrists, and the interview was conducted by one researcher and two research assistants. For the FGI, the subjects were given discussion topics, such as “suggestions on the feasibility and effectiveness of the community-based mental healthcare service model” and “suggestions for modification and supplementation of the model.” The interview lasted approximately 90 minutes, and all responses were recorded and consented to in advance.

The questionnaire responses were collected using an Internet survey of the mental health welfare center practitioners and hospital-based psychiatrists from December 28 to 31, 2020. The questionnaire for the mental health welfare center practitioners consisted of personal information, current status of case management and supervision, and directions pursued for the revised community-based mental healthcare service. The questionnaire for the psychiatrists consisted of personal information, number of patients in need of social rehabilitation in their hospital, and the status of service links and directions pursued for the revised community-based mental healthcare service.

A panel of 20 experts comprising 10 practitioners from the community mental health welfare center and 10 hospitalbased psychiatrists was configured for the Delphi investigations. The manager-level experts from the mental health welfare centers were selected from among deputy center heads and standing team heads who were recommended by the Seoul Mental Health Welfare Center; since this center is not only managed directly but also operated by consignment, 50% of each directly managed and entrusted operating institutions were selected. Psychiatrists from hospitals participating in this survey were the directors of outpatient and inpatient hospitals in Seoul who were recommended by the Seoul Psychiatric Association. The Delphi survey was conducted via email twice in total. The first assessment was conducted from January 28 to 30, 2021, and the second was conducted from February 5 to 7, 2021; all participants responded within the investigation deadlines. Each question in the survey was rated on a scale from completely disagree (1 point) to strongly agree (9 points). The content validity ratio (CVR) suggested by Lawshe [5] was used to verify the validity of the responses. In this study, agreement was judged based on the responses having 7 points or more on the 9-point scale. As the number of panelists in this study was 20, the minimum validity criterion was set at 0.42. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Soonchunhyang Hospital and adhered to the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki and principles of Good Clinical Practice (Approval number: 2020-12-062). Informed consent requirement was waived because only de-identified data were collected. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 28.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

The results of the study are as follows in the order of the FGI analysis, investigation with questionnaires, and Delphi surveys on the efficiency of the community-based mental healthcare model. First, based on the outcomes of the FGI, the current status and future directions of the community-based mental healthcare service were evaluated. The practitioners from the mental health welfare centers and hospital-based psychiatrists for the FGI were selected as shown in Table 1.

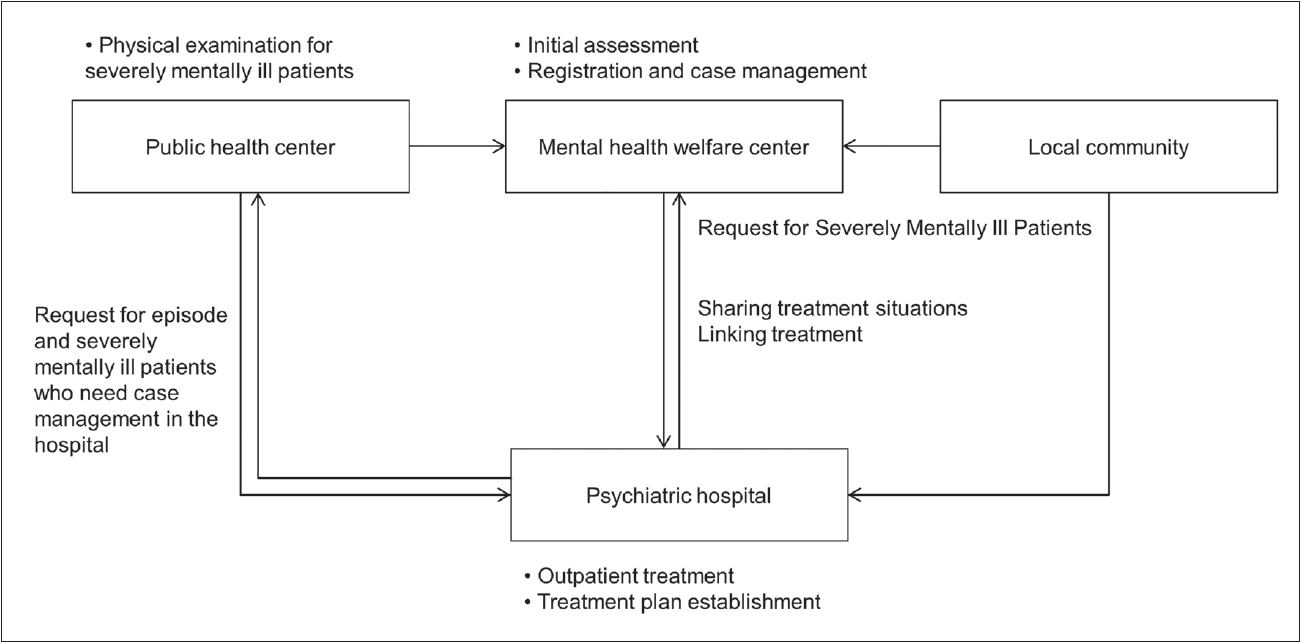

Regarding the current Seoul-type community-based mental care service (Figure 1), the practitioners from the mental health welfare center noted the following issues. Because of social prejudices or negative perceptions, the majority of highrisk mental health groups did not agree to be linked with a psychiatric hospital; they were eventually taken care of by the mental health welfare center, which in turn increased the burden of the center. Moreover, private for-profit institutions often tend to focus only on the symptomatic treatment of patients, so awareness of social rehabilitation through connection with community services is low. As rehabilitation is possible only when the patient has been treated, the importance of sharing information about the patients was emphasized, such as the treatment situation; further, it is important to maintain smooth communication between the hospital and center. The mental healthcare model through hospitals was preferred over the case-sharing model in that the separation between hospitals and centers can become ambiguous. In addition, the respondents were concerned that the high burden of administration in hospitals could be a constraint, so they suggested that a feasible reward system and the competences of the case managers in hospitals could be important. Currently, the basic physical health management for mentally ill patients is supported mainly by the metabolic syndrome center, health examination center of the public health center, and health programs of the public health center. The services for physical diseases that can be used by mentally ill people are also very poor, and the hospitalization of mentally ill patients with physical diseases is very difficult.

The FGI results from the psychiatrists were as follows. When hiring case managers affiliated with hospitals for directly linking patients with hospitals without going through the local mental health centers, there were concerns that the burden of the doctors directly connecting the patients to the case manager and the burden of administrative work would increase. In order for the hospital participation model to be executed successfully, it is necessary to prepare a specific system for the work of the case managers and secure spaces for these case managers in the outpatient bases of the hospitals. To compensate for this, the model was proposed to be used in hospitals focused on inpatients and chronic patients. Furthermore, sufficient budget should be secured, and the medical insurance numbers should be systematized. In the case of hospital-based psychiatrists, the case managers were preferred to be dispatched from local or metropolitan mental health welfare centers rather than directly hiring case managers affiliated with hospitals. A total of 98 practitioners from mental health welfare centers and 102 hospital-based psychiatrists participated in the survey. The demographic characteristics of the participants are displayed in Table 2.

The number of case management subjects of each of the practitioners at the mental health welfare center being 30 or more and less than 40 was maximum at 24.5%, followed by 20 or more and less than 30 (20.4%), and less than 10 (16.3%). The number of subjects with intensive case management was 3 or more and less than 5 for 34.7% of the scenarios, followed by 5 or more and less than 7 (31.6%), and less than 3 (17.3%). For the method of communication with the doctor or medical institution, 71.4% of the cases were from the outpatient clinic or involved direct communication with the doctor by phone, and 28.6% communicated with the doctor through as the subject or through their guardian. The mean satisfaction level of communication with the doctor or medical institution was 3.07 out of 5 (standard deviation [SD]=1.05), and 29.6% of the total surveyed subjects were satisfied with communication with the doctor or medical institution. The supervision satisfaction level was 3.82 points (SD=1.03) on average out of 5, and 64.2% of subjects were satisfied with the supervision. Regarding the appropriate supervision cycle, 48.0% answered once a month, followed by 21.4% once every 2 months, and 19.4% once every two weeks. The average number of appropriate supervision cases per hour was 2.63 (SD=1.58). About 30.6% of respondents showed willingness to participate in the case management project that integrated case management by medical institutions and mental health welfare centers, and 62.2% of the respondents expected that this model would help the center practitioners to communicate with doctors; the positive evaluation level of the model was an average of 3.57 out of 5 (SD=1.07).

The mean number of patients deemed necessary for case management in the hospital was 8.73 (SD=8.30). When the patients needed social rehabilitation, about 67.6% of the psychiatrists offered introductions to mental health welfare centers or related facilities, while 22.5% of psychiatrists contacted the mental health welfare centers or related institutions, and 9.8% of psychiatrists actively intervened during outpatient hours. Regarding the need to improve patients’ social rehabilitation methods, 84.0% of the respondents said yes, which was very high. Regarding the intention to participate in the case management project, 52.0% of the respondents noted their willingness to participate. On the question of whether hospitals were willing to hire mental health professionals as case managers if they received support for the case management operations, 44.8% expressed negative opinions against the positive opinions expressed by 25.5% of the respondents. On the other hand, for the model that dispatched mental health specialists to hospitals and regularly provided case management to patients, 49.0% positive opinions were received, which was higher than the 19.6% of negative opinions. For the appropriate supervision cycle, 48.0% responded once a month, followed by 32.4% once every two weeks, and 11.8% once every 2 months; the mean number of appropriate supervision cases per hour was 3.97 (SD=2.27). The most appropriate case cost per hour of supervision varied from 100,000 to 150,000 KRW (29.4%), followed by 150,000 to 200,000 KRW (23.5%), and 250,000 to 300,000 KRW (15.7%).

Of the 20 expert panelists who participated in the Delphi survey, 10 were psychiatrists working in hospitals, and the 10 staff from the community mental health welfare centers consisted of five mental health nurses, four mental health social workers, and one mental health clinical psychologist. According to the results of the first Delphi survey, those who frequently visited hospitals and were hospitalized more than twice a year, those with a first episode of mental illness, those with unstable chronic mental illnesses, those at risk of self-harm or suicide due to psychiatric problems but not included under crisis intervention, those who met the criteria for intensive case management among the recipients of discharge orders from the mental health review committee, and those recognized by the attending physicians as suitable for intensive case management by the local community were considered suitable candidates for the service target. For the question on the case management method, the following items showed significant CVRs: “link with mental health welfare center when case management is complete, and if it is rejected, it will be withdrawn;” “method of recognizing a case management subject for hospital registration as the performance of the mental health welfare center;” and “extending case management through evaluation once when an extension is necessary.” Moreover, according to the survey results, mental health education, family intervention, social skills training, early intervention service, and suicide crisis intervention were all suitable for case management services. Sufficient internal validity was confirmed for opinions regarding “supervision on the subject’s physical health management.” In addition, experts participating in the Delphi survey agreed that if a patient undergoing psychiatric treatment needs physical treatment, it would be appropriate to liaise with the healthcare team of the public health center or provide physical health services to the patients according to the care plan developed by the healthcare team.

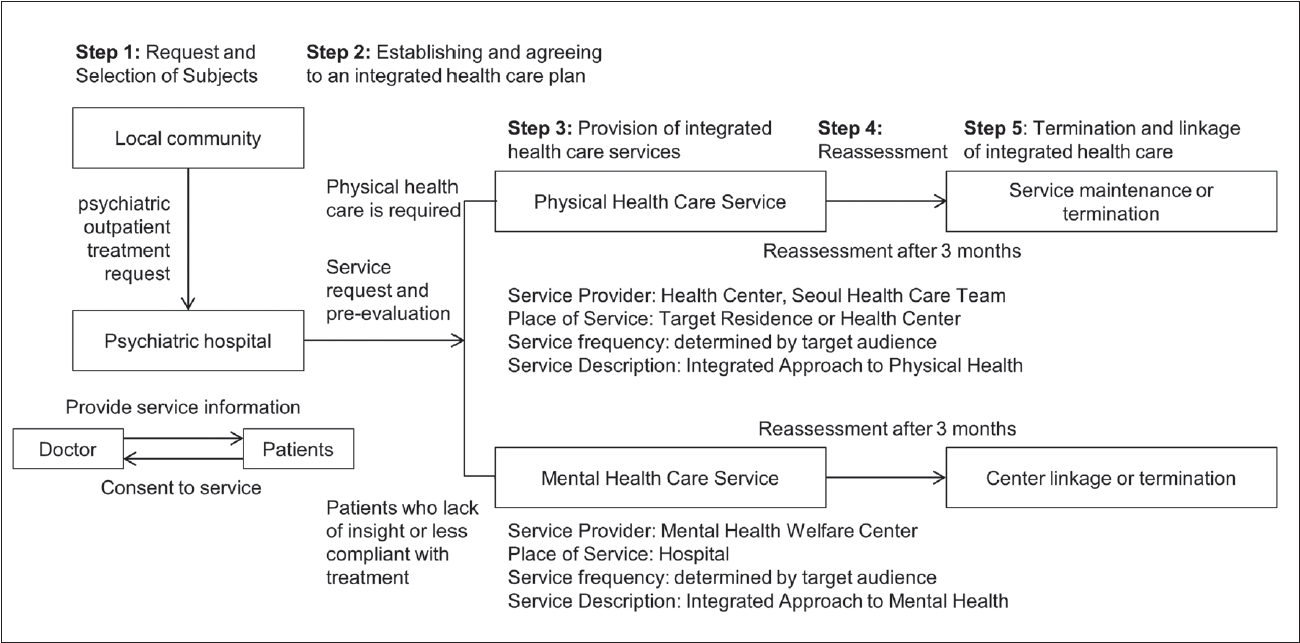

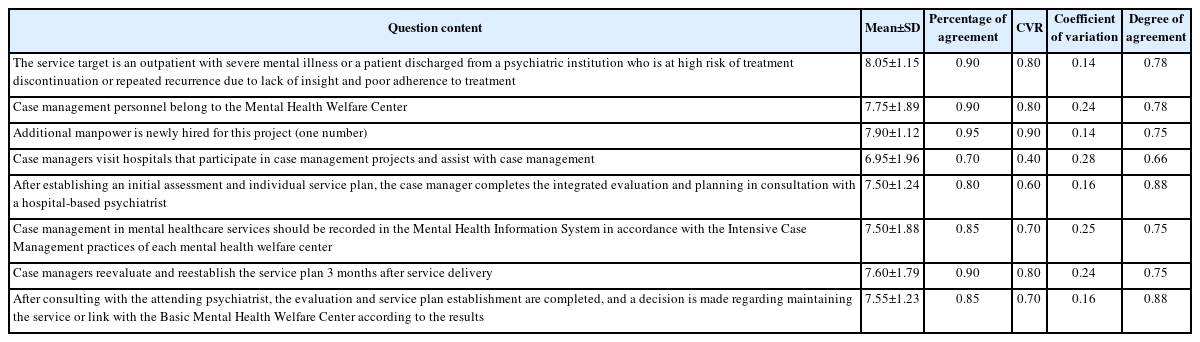

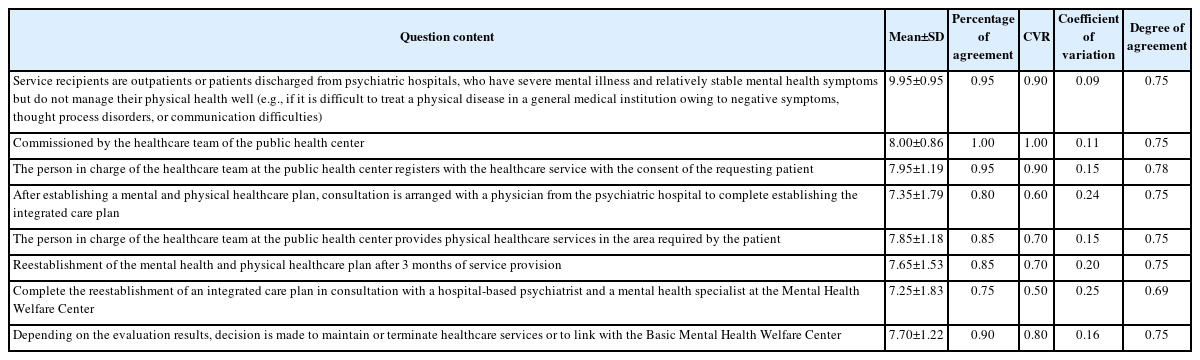

There were many items in the first Delphi survey that the panelists did not agreed upon, and the model was revised based on these items (Figure 2) before the second Delphi survey was conducted. Thus, the model for providing case management through dual physical and mental health services did not achieve a sufficient CVR (0.10). From the results of the second Delphi survey, mental health service subjects were suggested as being considered patients with severe mental illness among the outpatients or as discharged from psychiatric institutions with high risk of treatment discontinuation or repeated recurrence owing to lack of insight and poor adherence to treatment. In addition, it was recommended that the case management personnel be assigned from the mental health welfare center and that additional personnel be newly hired for the project. Sufficient internal validity was confirmed in case of the following items: “after establishing an initial assessment and individual service plan, the case manager completes the integrated evaluation and planning in consultation with a hospital-based psychiatrist;” “case management in mental healthcare services should be recorded in the Mental Health Information System in accordance with the Intensive Case Management practices of each mental health welfare center.” It was also suggested that reevaluations be conducted after 3 months of service to create a new plan. The results additionally suggested that after consulting with the attending psychiatrist, the evaluation and service plan establishment should be completed and a decision must be made to either maintain the service or link with a basic mental health welfare center (Table 3). Combining the survey results on physical health services, persons with severe mental illness treated as outpatients or as patients discharged from psychiatric hospitals and having relatively stable mental health symptoms but managing their physical health poorly should be the subjects of the service. Moreover, physical health services should be provided by the healthcare team of the public health center. After establishing a combined mental and physical healthcare plan, a consultation with a hospital-based psychiatrist was emphasized to complete the establishment of an integrated care plan. The physical healthcare plan also needs to be reevaluated after 3 months and reestablished in consultation with a hospital-based psychiatrist as well as a mental health specialist at the mental health welfare center. Based on the evaluation result, it is proposed that a decision be made on whether to maintain or terminate healthcare services or to link with a basic mental health welfare center (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

With the revision of the Mental Health Welfare Act in 2017, the standards for forced hospitalization have become stricter in Korea, and the demand for community-based mental healthcare is increasing. However, community-based mental health services are currently underprepared, and quality improvement has become a critical need. Therefore, this study attempted to establish a new integrated care model to solve the problems of community-based mental health services, which often have high case management burden and service segmentation. Therefore, based on an FGI, questionnaires, and two Delphi surveys targeting mental health welfare center practitioners and hospital-based psychiatrists, a community-based integrated care model is proposed.

The future directions for the community-based mental healthcare service is as follows. First, the service delivery system must be strengthened. Mental health services should be offered for continuity of prevention, early intervention, treatment, protection, rehabilitation, and social integration. Mental healthcare focuses on continuity of treatment, rehabilitation, and social integration, which necessarily require a linkage model utilizing community resources, particularly linkage and integration with medical institutions in the community. Second, mental healthcare should improve the quality of service so that the needs of the subjects are met. Owing to the nature of mental health services, the quality of service is closely related to manpower quality, so supervision of highquality manpower maintenance and high intensity are required. Third, a high level of accessibility is necessary for the use of anyone needing mental healthcare; for this, both physical accessibility and high recognition rate for services are required. In addition, prejudices against mental health services are obstacles to accessibility, so efforts are needed to lower prejudice. Fourth, even in the case of severely mentally ill patients with physical health problems, an integrated healthcare model is needed so as to provide necessary care services in an integrated manner.

Based on the above results, the Seoul-type integrated healthcare model consists of five stages, whose first step is requesting and selecting subjects. Among outpatients or discharged patients, if there is high risk of treatment discontinuation or recurrence due to lack of insight and poor adherence to treatment, mental healthcare services are requested; if the psychiatric symptoms are relatively stable but physical health management is inadequate, physical healthcare services are requested. In addition, subjects registering for case management services in their local community are referred to psychiatric institutions for service linkage.

In the case of mental healthcare services, the following steps are taken. Step 2 involves service registration, integrated evaluation, and planning. A case manager from the mental health welfare center visits the relevant psychiatric hospital on a designated day and registers the requesting patient at the basic mental health welfare center. Once the case manager establishes an initial assessment and individual service plan, they complete the integrated evaluation and planning with advice from the hospital-based psychiatrist. In step 3, a case manager from the mental health welfare center visits the relevant psychiatric hospital once a week on a designated day to provide 40 minutes of intensive case management, including mental health education. In step 4, a psychiatrist supervises the case management for the patient once a month through the case manager dispatched to the hospital. In step 5, the case manager reestablishes the evaluation and service plan after 3 months of service provision, consults with the psychiatrist, completes the integrated evaluation and service plan, and decides to maintain the service or link the patient with the basic mental health welfare center.

The physical healthcare service is implemented as follows. In step 2, the healthcare team registers the requesting patient for the healthcare service with their consent, establishes mental and physical healthcare plans, and consults a hospital-based psychiatrist to establish an integrated care plan. In step 3, the healthcare team provides healthcare services in the physical health area required by the patient. In step 4, after 3 months of service provision the mental and physical healthcare plans are reestablished along with the integrated care plan in consultation with a hospital-based psychiatrist and the mental healthcare center. In step 5, the healthcare service is maintained, terminated, or linked with a basic mental health welfare center according to the case evaluation results.

The discussion in the current study is limited to community-based mental healthcare services located in the city of Seoul. The welfare service for each municipality differs from the others. Moreover, there are some limitations to this study in that it does not reflect the opinions of the service recipients and that only psychiatrists and mental health welfare center employees providing service are included. Nevertheless, this study is significant as it considers qualitatively providing integrated community-based mental healthcare services to mentally affected people based on a direct questionnaire as well as the FGI of mental health professionals, which could allow such needs to be reflected in the field in the future.

Considering these together, the Seoul-type mental healthcare model is intended to allow community medical institutions to provide medical treatment as well as cooperate with mental health welfare institutions to provide optimal mental health services to promote effective treatment and return to community. In addition, it is expected to contribute to the establishment of services by multidisciplinary mental health experts and the expansion of new jobs in mental medical institutions. The multidisciplinary integrated management is expected to contribute considerably to securing a safety net for high-risk subjects and society, in addition to reducing their medical and socioeconomic burden.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Jong Woo Paik, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Data curation: Soo Bong Jung, Eun Jin Na, Jee Hye Bae, Jong Woo Paik, Hwo Yeon Seo, Jee Hoon Sohn, Hae Woo Lee, Jeung Suk Lim, Mi Jang, Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Formal analysis: Soo Bong Jung, Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Funding acquisition: Hwa Young Lee. Methodology: Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Project administration: Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Resources: Soo Bong Jung, Eun Jin Na, Jee Hye Bae, Jong Woo Paik, Hwo Yeon Seo, Jee Hoon Sohn, Hae Woo Lee, Jeung Suk Lim, Mi Jang, Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Software: Sra Jung, Soo Bong Jung, Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Supervision: Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Validation: Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee. Visualization: Sra Jung. Writing— original draft: Sra Jung. Writing—review & editing: Sra Jung, Soo Bong Jung, Sung Joon Cho, Hwa Young Lee.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Seoul Health Foundation.