Suicidal Thinking Among Patients With Spinal Conditions in South Korea: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Chronic pain increases the risk of suicide because it is often accompanied by depressive symptoms. However, the existing information regarding suicidal thinking in patients with chronic pain such as spinal conditions is insufficient. We aimed to examine the prevalence of suicidal thinking and the factors associated with it among patients with spinal conditions.

Methods

Data from the National Health Insurance Service database in South Korea were used in this population-based, cross-sectional study, and 2.5% of adult patients diagnosed with spinal conditions (low back pain and/or neck pain) between 2018 and 2019 were selected using a stratified random sampling technique. Patient Health Questionnaire–9 was used to determine the presence of suicidal thoughts and depressive symptoms.

Results

33,171 patients with spinal conditions were included in this study. Among them, 5.9% had suicidal thinking and 20.7% had depressive symptoms. In the multivariable logistic regression model, old age, male sex, and employment were associated with a decreased prevalence of suicidal thinking. Current smokers, previous smokers, medical aid program recipients, and patients with mild-to-moderate or severe disability showed increased suicidal thinking. Underlying depression, bipolar disorder, insomnia disorder, and substance abuse were also associated with increased suicidal thinking.

Conclusion

In South Korea, 5.9% and 20.7% of patients with spinal conditions had suicidal thoughts and depressive symptoms, respectively. Some factors were associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts among patients with spinal conditions. Our results suggest that screening for these factors can help prevent suicide in patients with spinal conditions.

INTRODUCTION

Spinal conditions such as low back pain (LBP) and neck pain (NP) are critical public health problems that have been the leading causes of disability for several years [1,2]. Approximately one-third of the adult population in the United States has spinal conditions such as LBP and/or NP [3]. Approximately half of the patients with spinal conditions report disability or pain that requires healthcare consumption [4]. Thus, spinal conditions are an important public health issue.

Suicide is a major public health problem, accounting for 1.3% of all deaths worldwide in 2019 [5]. In South Korea, suicide is a serious public health problem, with a suicide prevalence of 24.6 per 100,000 population in 2019, the highest among Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development countries [6]. Moreover, the mortality due to suicide among the total deaths was 5.26% (84,934 deaths by suicide/1,615,288 total deaths) from 2011 to 2016 in South Korea [7]. Chronic pain increases the risk of suicide [8] because it is often accompanied by depressive symptoms [9]. Cheatle et al. [10] reported a high prevalence of suicidal ideation in a population with chronic pain. For patients with spine conditions, studies reported that suicidal ideation was higher in patients with LBP than in those without [11,12]. However, the previous studies analyzed small samples: 32 patients with LBP[11] and 159 patients with LBP [12]. Thus, more research on this topic is needed with a large sample using a nationwide registration database.

Therefore, we aimed to examine the prevalence and factors associated with suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions in South Korea. We hypothesized that some factors such as age, sex, underlying physical comorbidities, socioeconomic status, smoking, and other underlying psychiatric comorbidities may be associated with suicidal thinking [13].

METHODS

Study design and ethics statement

This cross-sectional study included randomly sampled participants from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database from 2018 to 2019. All procedures contributing to this study complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB approval number: X-2105-685-901). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB because the data were analyzed anonymously after masking the individual and sensitive information of the study population.

Data source

The NHIS database was used as the data source. Since it is the sole public health insurance system in South Korea, all individuals in South Korea, including military personnel, children, and unemployed persons, are required to be registered in the NHIS. Additionally, foreigners are obliged to subscribe to health insurance services if they have stayed in South Korea for more than six months. The NHIS database contains information regarding all disease diagnoses and prescriptions for any drug and/or procedure. The International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Issues, 10th revision (ICD-10) is used to register disease diagnoses in the NHIS database. The medical record technician from the Big Data Center in the NHIS extracted and provided the data for this study after approval of the study protocol by the NHIS Ethics Committee (NHIS approval number: NHIS-2021-1-615).

Study population

Adult patients (aged ≥20 years) who were diagnosed with spinal conditions and visited an outpatient clinic or hospital in South Korea from January 1, 2018 to December 31, 2019 (2 years) were included in this study. Patients who had been diagnosed with LBP and/or NP at least once during the study period were included and considered as patients with spine conditions. We used ICD-10 codes of NP and/or LBP in the Global Burden Disease Study 2013 report, which classified six main categories of musculoskeletal disorders: rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, LBP, NP, gout, and other musculoskeletal disorders [14]. This classification of ICD-10 codes of NP and/or LBP was also used in an epidemiologic study in the Eastern Mediterranean Region [15]. Thus, the ICD-10 codes G54.1, G54.3, G54.4, G57.0–G57.12, M43.2–M43.5, M43.8, M43.9, M45–M49, M49.2–M49.89, M51–M51.9, M53, M53.2–M54, M54.1–M54.18, M54.3–M54.9, M99, and M99.1–M99.9 were used to extract patients with LBP, while the codes G54.2, M50–M50.93, M53.0, M54.0–M54.09, and M54.2 were used to extract patients with NP.

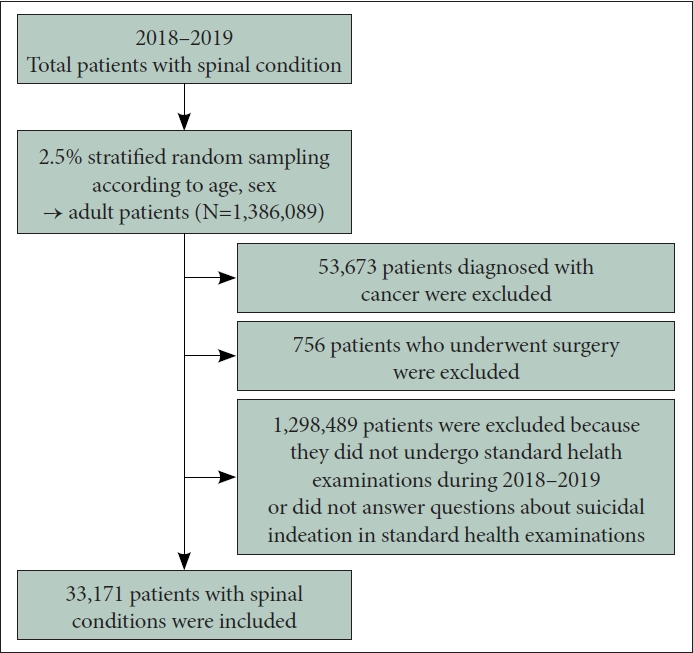

Between 2018 and 2019, over 55,000,000 the number of diagnosis cases visited the outpatient clinic or were admitted to the hospital with spine conditions. The data of 2.5% of adult patients were then extracted using a stratified random sampling technique, considering age and sex as exclusive strata for sampling. Using this sampling strategy, we ensured that the age distribution and sex ratio of the sample of patients with spinal conditions was similar to that of the entire population with spinal conditions. Finally, 1,386,089 patients were sampled using a stratified random sampling method with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) [16]. Next, we excluded 53,673 patients diagnosed with cancer and 756 patients who underwent surgery, because cancer or surgery may affect mood disorders. In addition, 1,298,489 patients were excluded because they did not undergo standard health examinations during 2018–2019 or did not answer questions about suicidal ideation in standard health examinations. In South Korea, people aged ≥40 years are recommended to undergo standardized health examinations every 2 years as a part of national health planning [17]. Finally, 33,171 patients with spinal conditions were included in this study (Figure 1).

Study objectives

The primary endpoint of this study was suicidal thinking, which was evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9). Question 9 of the PHQ-9 asks about suicidal thought within the last 2 weeks [18,19]. Response options include “not at all” (Q9=0), “several days” (Q9=1), “more than half the days” (Q9=2), or “nearly every day” (Q9=3). In this scale, Q=1, 2, and 3 were considered to indicate the presence of suicidal thinking. As a secondary endpoint, the scores for the PHQ-9 depressive scale (0–27 points) were also evaluated [20]. Using the depressive scale scores, the patients were divided into four groups: no depressive symptoms (0–4 points), mild depressive symptoms (5–9 points), moderate depressive symptoms (10–19 points), and severe depressive symptoms (20–27 points). The PHQ-9 questionnaire for the depressive scale is presented in Supplementary Table 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement).

Covariates

Data for household income level, residence, disability, and pain medication prescriptions were collected as covariates on the basis of our previous study [21]. In addition, body mass index data were recorded and categorized into five groups (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, 30.0–34.9, and ≥35.0 kg/m2). The patients were divided into three groups based on their smoking status: never, previous, and current smokers. Data for underlying comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, myocardial infarction (MI), angina, and stroke, as well as underlying psychiatric morbidities, such as depression (F32, F33, F34.1), bipolar disorder (F31), insomnia disorder (G47, F51), substance abuse (F10–F19), and schizophrenia (F20), were also collected. For the treatment of spinal conditions, receipts of block procedures were collected, which included all block procedures of the spinal nerve plexus, root, ganglion, and epidural nerve block. However, radiofrequency ablation was not included among these block procedures. Data on patient disability status from 2018 to 2019 were extracted. All individuals with disabilities were registered in the NHIS database to enable them to receive benefits from South Korea’s social welfare system. Patients were initially categorized into six groups based on disability severity, and these groups were subsequently consolidated into two groups: 1) severe disability (patients with grades 1–3 disabilities) and 2) mildto-moderate disability (those with grades 4–6 disabilities). The pain medications used (≥30 days) were classified into opioids, gabapentin or pregabalin, paracetamol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Statistical analyses

The clinicopathological characteristics of patients with spinal conditions are presented as mean values with standard deviation (SD) and numbers with percentages for continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively. For comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between the suicidal thinking group and the nonsuicidal thinking group, the t-test and chi-square test were used for continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively. We constructed a multivariable logistic regression model for the presence of suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions to examine factors independently associated with the presence of suicidal thinking. All covariates were included in the model for multivariable adjustment and results were presented as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Hosmer–Lemeshow statistics were used to confirm that the goodness-of-fit in the multivariable model was appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

RESULTS

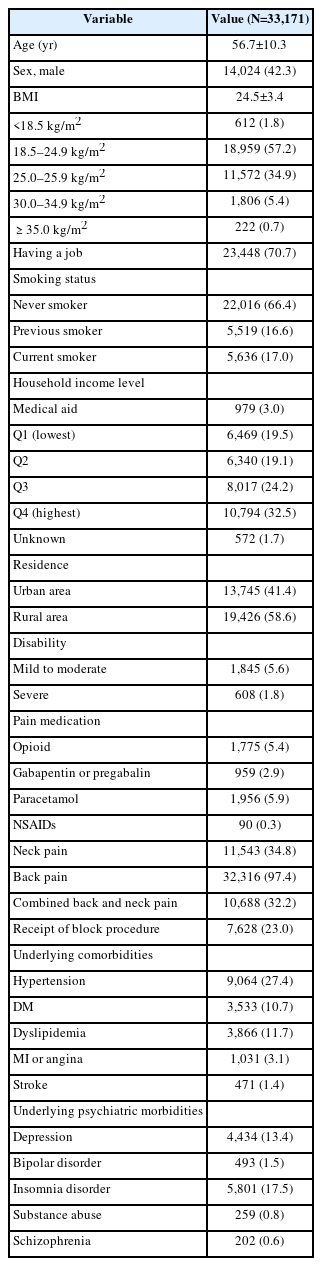

The clinicopathological characteristics of patients with spinal conditions are presented in Table 1. The mean patient age was 56.7 (SD: 10.3) years, and the proportion of male patients was 42.3% (14,024/33,171). Table 2 shows the results of the survey on suicidal thinking and depressive scales using the PHQ-9. Responses to questions on suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions included “not at all” (n=31,228, 94.1%), “several days” (n=1,502, 4.5%), “more than half the days” (n=272, 0.8%), or “nearly every day” (n=169, 0.5%). Responses to the questions of depressive scales among patients with spinal conditions included no depressive symptoms (n=26,304, 79.3%), mild depressive symptoms (n=4,983, 15.0%), moderate depressive symptoms (n=1,673, 5.0%), and severe depressive symptoms (n=211, 0.6%).

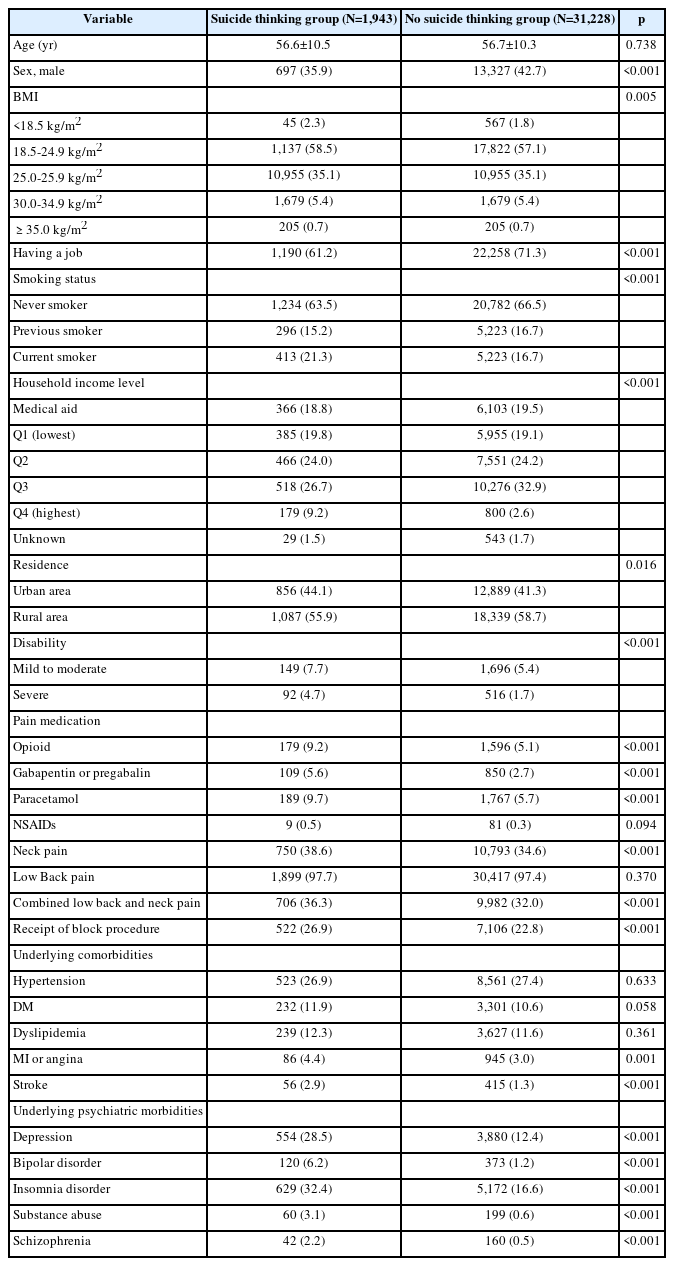

Table 3 shows the results for the comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between the suicidal thinking group (n=1,943) and the no suicidal thinking group (n=31,228). The proportion of male participants was higher in the no suicidal thinking group (42.7%, 13,327/31,228) than in the suicidal thinking group (35.9%, 697/1,943; p<0.001). The proportion of those who had a job was higher in the no suicidal thinking group (71.3%, 22,258/31,228) than in the suicidal thinking group (61.2%, 1,190/1,943; p<0.001). The proportion of current smokers was higher in the suicidal thinking group (21.3%, 413/1,943) than in the no suicidal thinking group (16.7%, 5,223/31,228; p<0.001).

Comparison of clinicopathological characteristics between the suicidal thinking group and the no suicidal thinking group

Table 4 shows the results of the multivariable logistic regression model for suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions. Older age (aOR=0.99, 95% CI=0.99, 0.99; p<0.001), male sex (vs. female; aOR=0.58, 95% CI=0.50, 0.66; p<0.001), and having a job (vs. unemployment; aOR=0.81, 95% CI=0.73, 0.90; p<0.001) were associated with a decreased prevalence of suicidal thinking. Current smokers (vs. never smokers; aOR=1.77, 95% CI=1.52, 2.06; p<0.001), previous smokers (vs. never smokers; aOR=1.46, 95% CI=1.24, 1.72; p<0.001), medical aid program group (aOR=1.76, 95% CI=1.40, 2.21; p<0.001), mild-to-moderate disability (aOR=1.21, 95% CI=1.01, 1.46; p=0.041), and severe disability (aOR=1.86, 95% CI=1.43, 2.43; p<0.001) were associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts. Underlying depression (aOR=1.79, 95% CI=1.58, 2.02; p<0.001), bipolar disorder (aOR=1.99, 95% CI=1.55, 2.54; p<0.001), insomnia disorder (aOR=1.65, 95% CI=1.47, 1.84; p<0.001), and substance abuse (aOR=1.95, 95% CI=1.41, 2.71; p<0.001) were associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal thinking.

DISCUSSION

This population-based cross-sectional study showed that 5.9% (1,943/33,171) of the patients with spinal conditions had suicidal thoughts. Significantly, 0.8% and 0.5% of the patients with spinal conditions had suicidal thoughts on “more than half the days” and “nearly every day,” respectively. Moreover, 20.7% of the patients with spinal conditions had depressive symptoms. Some factors associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts included female sex, unemployment, current and previous smoking, poor economic status, underlying disability, and coexisting psychiatric morbidities (depression, bipolar disorder, insomnia disorder, and substance abuse). Although some factors such as age and sex were nonmodifiable risk factors, some factors such as socioeconomic status, smoking, and coexisting psychiatric morbidities were modifiable risk factors for suicidal thinking. Therefore, a policy approach to these patients should be determined by focusing on these modifiable factors of suicidal thinking among patients with spine conditions.

The prevalence of suicidal thoughts has been reported in several populations. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was reported to be 10.72% among Chinese college students [22] and 11.1% among medical students from 43 countries [23]. Moreover, the lifetime prevalence estimate of suicidal ideation was reported to be 3.1% in the Chinese population. However, one study assessing 466 patients with chronic non-cancer pain, similar to our study, reported that 28% of patients with chronic non-cancer pain had suicidal ideation [10]. In a white paper on suicide prevention from 2021 [24], the prevalence of suicidal ideation was 4.6% among all adults in South Korea, which was slightly lower than that of suicidal ideation (5.9%) among people with spinal conditions in this study. However, there has not been enough information regarding the prevalence of suicidal ideation among patients with spinal conditions, so more investigation is needed on this topic.

Importantly, the multivariable logistic regression model showed that socioeconomic status-related factors, such as low economic status and unemployment, were potential risk factors for suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions. The medical aid program group in South Korea was considered to include individuals who are too poor to pay their insurance premiums or have difficulty supporting themselves financially [25], and a government program was developed to cover almost all medical expenses and help reduce the burden of medical costs on these individuals. Poor economic status was shown to be a risk factor for suicidal behaviors in a previous study [26], and suicide and economic poverty were important factors associated with suicidal ideation in low-income and middle-income countries [27]. Moreover, economic recession and unemployment are associated with an increased risk of suicidal behavior at both the population and individual level [28]. Thus, these previous studies suggest that low income and unemployment are potential risk factors among patients with spinal conditions.

Previous and current smoking habits have also been associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts among patients with spinal conditions. A previous study reported an association between cigarette smoking and suicide among psychiatric inpatients [29]. Another recent cohort study reported a dose-response relationship between smoking and suicidal ideation, such that the higher the daily smoking rate, the greater the suicidal ideation, even after controlling for depression, alcohol use, and drug use [30]. Moreover, heavy daily smoking in 18-year-old psychiatric inpatients was associated with an increased risk of suicide attempts [31]. We showed that both current and previous smoking may be potential risk factors for suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions, suggesting that patients with spinal conditions who have a history of smoking need to be screened as a high-risk population for suicide.

Coexisting psychiatric morbidities, such as depression, bipolar disorder, insomnia disorder, and substance abuse, were associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions. Both depression and bipolar disorder are well-known risk factors for suicidal thinking [32,33]. Substance abuse has been commonly reported to coexist with suicidal ideation [34]. Insomnia symptoms were also uniquely associated with the frequency of suicidal ideation in a previous study [35], consistent with our findings. Thus, screening for these psychiatric morbidities and smoking in patients with spinal conditions may help identify a high-risk population for suicide.

Female sex, underlying disability, and MI or angina were also risk factor for suicidal thinking among patients with spinal conditions. Female individuals are a high-risk population for both depression and suicidal thinking [36]. Patients who had disability had chronic medical conditions that were related to impaired physical function. Moreover, they might have difficulty in maintaining daily life, which led to an increased prevalence of suicidal thinking. There was close relationship between underlying disability and increased risk of suicide [37]. A previous study reported that at least 14% of patients with coronary heart disease and hypertension indicated suicidal ideations within the last 2 weeks [38]. The current study’s results also suggested that patients with spine conditions and coronary heart disease should be carefully monitored as a high-risk group regarding suicidal risk.

This study had several limitations. First, for data extraction, a 2.5% stratified random sampling technique was used considering the age distribution and sex ratio. Thus, there may have been differences between the sampled patients with spinal conditions and those in the population in South Korea. Second, we did not assess the severity of spinal conditions in this study. The duration, stage, and severity of pain in patients with spine conditions (LBP and/or NP) may influence their mood and suicidal thinking. Third, the generalizability of the results of this study may be limited because the health insurance systems in many countries are different. Fourth, we only assessed suicidal thinking and did not evaluate the completion of suicide because the NHIS database did not provide the relevant data. Fifth, we used the PHQ-9 to evaluate suicidal thinking. However, there have been some criticisms about the limitation of the PHQ-9 as screening tool [39]. The questions in the PHQ-9 are closed questions, and some patients who had suicidal thinking currently could not be detected using this tool. Lastly, as this study had a cross-sectional design, it is not possible to suggest a causal relationships because it is not possible to know the temporal relationship between factors associated with suicidal ideation and suicidal ideation.

In conclusion, in South Korea, 5.9% and 20.7% of patients with spinal conditions had suicidal thoughts and depressive symptoms, respectively. Some factors associated with an increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts included female sex, unemployment, current and previous smoking, poor economic status, underlying disability, and coexisting psychiatric morbidities (depression, bipolar disorder, insomnia disorder, and substance abuse).

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2023.0072.

Patient Health Questionnaire‒9

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Tak Kyu Oh, In-Ae Song. Data curation: Hye Yoon Park. Formal analysis: Tak Kyu Oh. Investigation: Tak Kyu Oh. Methodology: In-Ae Song. Project administration: Tak Kyu Oh, In-Ae Song. Writing—original draft: Tak Kyu Oh. Writing—review & editing: Hye Yoon Park, In-Ae Song.

Funding Statement

None