Development of a Korean Version of the Child Mania Rating Scale: Korean Validity and Reliability Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Clinical rating scales are essential in psychiatry. The Young Mania Rating Scale is the gold standard for assessing mania. However, increased attention to pediatric bipolar disorder has led to the development of the Child Mania Rating Scale (CMRS), which is a parent-reported rating scale designed to assess mania in children and adolescents. This study aimed to translate the CMRS into Korean and assess the validity and reliability of the Korean version of the CMRS (K-CMRS).

Methods

The original English version of the CMRS has been translated into Korean. We enrolled 33 patients with bipolar disorder and 26 patients with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). All participants were evaluated using the translated K-CMRS, Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), and ADHD Rating Scale.

Results

The Cronbach’s α was 0.907. Correlation analyses between K-CMRS and MDQ scores yielded significant positive correlations (r=0.529, p=0.009). However, the factor analysis was unsuccessful. The total K-CMRS scores of bipolar disorder and ADHD patients were compared. However, the differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

The K-CMRS showed good internal consistency and reliability. The correlation between the K-CMRS and MDQ scores verifies its validity. The K-CMRS was designed to assess and score manic symptoms in children and adolescents but had difficulties in differentiating between bipolar disorder and ADHD. It is a valuable tool for evaluating the presence and severity of manic symptoms in pediatric patients with bipolar disorder.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical rating scales are essential tools in psychiatry. They help clinicians to systematically evaluate and quantify symptoms, behaviors, and other relevant factors related to various psychiatric disorders. Rating scales provide a standardized method for measuring symptoms, allowing clinicians to monitor symptom progression and treatment effects over time. They also facilitate communication between clinicians and patients by providing a common language to describe the symptoms and their severity. This common language is also necessary for academic research as a rating scale that aids in diagnosing psychiatric disorders with more objective information than pure clinical judgment.

Many rating scales have been developed for the diagnosis and evaluation of bipolar disorder patients [1-5]. The Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) is currently considered the gold standard owing to its high reliability and validity [6]. It has been translated and tested for reliability and validity in multiple languages [7-11]. YMRS has been extensively used in multiple studies and clinical trials; however, it has some limitations. The YMRS was designed to be used by a trained clinician and, therefore, has limitations in its use for screening purposes or large groups. Additionally, the items were designed to target adult patients with mania, which makes it relatively difficult to apply to children and adolescents. The number of pediatric bipolar disorder patients although has been growing. Previous research stated that in the US, office-based visits of bipolar disorder patients under 20 years increased from 25 (1994–1995) to 1,003 (2002–2003) per 100,000 population [12]. Naturally the need for an instrument for assessing pediatric bipolar disorder has also risen. Previous ratting scales like the Bech-Rafaelsen Mania Scale or the Manic State Rating Scale were already proven to be valid and reliable but were not targeted and tested for younger patients [3,13]. The Child Behavior Checklist–Mania Scale is another scale for the assessment of pediatric mania but was only validated for children over 11 years [14]. The Child Mania Rating Scale (CMRS) on the other hand was developed for children between the ages of 5 and 17, and is a modified version of the YMRS, which is the current gold standard for rating manic symptoms [15].

The CMRS is a parent-reported rating scale designed for assessing mania in children and adolescents and has been proven to be reliable and valid. Unlike the YMRS, the CMRS has not yet been translated into many languages, despite its high value. The increasing demand for international standardized research on pediatric bipolar disorder calls for valid and reliable rating scales that can be used in non-English speaking countries [16,17]. Using this tool with proven reliability and validity, clinicians can quantify and observe changes in the degree of mania symptoms in children and receive help in clinical judgment. According to data from the National Health Insurance Service, bipolar disorder is increasing in patients of all age groups in Korea; however, younger patients show the largest increase. The average annual increase in prevalence rate by age group was 8.48% for those aged 0–29 years from 2008 to 2017 [18]. The continuous growth of bipolar disorder populations calls for additional attention to this topic.

This study aimed to aid clinicians and researchers by translating the original English version of the CMRS into Korean and developing and assessing the Korean version of the CMRS (K-CMRS).

METHODS

CMRS translation and adaptation

Two researchers independently translated the original English version of the CMRS into Korean. The two versions were then compared and combined into a final version (Supplementary Material in the online-only Data Supplement). The final version was back-translated into English by a professional translation service and compared with the English version. Adjustments were made until no significant differences were observed between the two versions.

Subjects

Patients with bipolar disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were enrolled for comparison because manic symptoms in pediatric patients are often very similar to ADHD symptoms, resulting in frequent confusion between the two disorders. A total of 33 patients with bipolar disorder and 26 patients with ADHD were enrolled in the study. Bipolar disorder and ADHD were initially diagnosed by trained child and adolescent psychiatrists based on the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [19]. Clinical diagnosis was confirmed using the Korean version of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) [20], a semi-structured diagnostic interview. All patients were between the ages of 6 and 17 and were prospectively enrolled at the Psychiatry Department of Korea University Guro Hospital for inpatient or outpatient visits between June 2017 and April 2020. Patients did not receive any monetary compensation for participation.

Patients were excluded if they 1) did not meet the diagnostic criteria during the interview, 2) had any concurrent medical or neurological conditions that might affect their symptoms, or 3) had intelligence quotient (IQ) scores below 70 as measured by the Korean version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Fourth Edition [21]. Patients diagnosed with comorbid anxiety disorders were excluded from the study to obtain a more precise diagnosis.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients and their parents or legal guardians, if applicable. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea University Guro Hospital (IRB No. 2017GR0217).

Evaluation

We evaluated all participants using the translated K-CMRS by their parents or legal guardians. All participants completed the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) [22] and ADHD Rating Scale [23]. Cronbach’s α was calculated to assess the internal consistency of the K-CMRS. Student’s t-test was used to assess the discriminatory power of the K-CMRS between the bipolar disorder and ADHD patient groups.

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

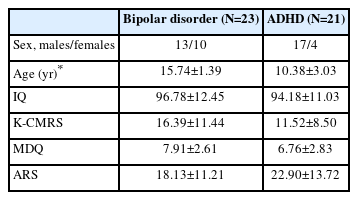

Of the 59 enrolled patients, two were excluded because they had IQ scores below 70, five because they failed to pass the K-SADS-PL diagnostic interview, and six because they withdrew their consent. Two bipolar disorder patients were excluded because of a comorbid diagnosis of anxiety disorder. In total, 23 patients with bipolar disorder (13 males and 10 females) and 21 patients with ADHD (17 males and 4 females) were included in the final analysis. Table 1 the demographic data and clinical variables of the patient groups.

The Cronbach’s α was 0.907. The removal of any item led to a decrease of Cronbach’s α except for two items: item 5, decreased need for sleep, and 14, disinhibited. The changes in Cronbach’s α values after the removal of each item are presented in Table 2.

Correlation analyses between the K-CMRS and MDQ scores in bipolar disorder patients yielded significant positive correlations, resulting in a good concurrent validity (r=0.529, p<0.01).

Factor analysis was attempted to explore possible simplifications. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was calculated to be 0.353, which is insufficient for suitable factor analysis.

The total K-CMRS scores of the bipolar disorder patients and ADHD were compared to assess the discriminatory power of the K-CMRS. The mean total K-CMRS score of bipolar disorder patients was 16.39±11.44, whereas that of ADHD patients was 11.52±8.50. This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.119).

DISCUSSION

This is the second non-English adaptation of the CMRS, following the Brazilian version published in 2021 [24]. The Brazilian version was translated and reviewed by 15 experts and 21 parents/guardians of a representative children/adolescent population. The authors showed a content validity coefficient of 0.95 and an agreement index above 86%.

This study demonstrated that the K-CMRS has good internal consistency and reliability. Cronbach’s α was 0.907, which was lower than that of the original English version (0.96); however, it was considered reliable. Moreover, an excessively high Cronbach’s α value may suggest that some items are redundant; therefore, a value of 0.90 is often recommended [25].

The correlation between the K-CMRS and MDQ scores was measured to verify concurrent validity. The indicated correlation coefficient is similar to previous multilingual versions of mania rating scales, resulting in good concurrent validity [8,9,11]. The MDQ was initially designed for use with adults, but adolescents older than age 12 can answer the MDQ. A version of the MDQ specifically targeted adolescents was also developed but had yet to be translated into Korean at the time of this study. The Korean version of the MDQ, published in August 2018, showed a sensitivity of 0.90 and specificity of 0.92 when used to screen for adolescent bipolar disorder [26]. The correlation between K-CMRS and MDQ scores could have been even higher if the adolescent version had been available. It must be noted that the MDQ and K-CMRS share some similarities but have a defining difference. The MDQ was developed strictly for screening bipolar disorder, whereas the K-CMRS was designed to assess and score manic symptoms in children and adolescents [26].

The K-CMRS scores of bipolar disorder and ADHD patients were compared to assess the discriminatory parameters of the scale. The scores were higher in the bipolar disorder group; however, this difference was not statistically significant. These two conditions are infamous for their high comorbidity and similarities, and researchers often fail to distinguish them using the CMRS standalone [27-29]. The developers of the original CMRS, Pavuluri stated that symptoms of bipolar disorder and ADHD are difficult to differentiate from each other and reported that the discriminative sensitivity of the CMRS was 0.82 for the two disorders [30]. Differential diagnosis is often challenging because of the many shared features between the two disorders. This problem is particularly notable if rating tools are self-reported or reported by parents, guardians, or teachers. Carlson and Blader [31] reported that parent and teacher corroboration of high CMRS scores led to an increased risk of externalizing disorders, including ADHD. These findings show that the CMRS might not be sufficient for early differential diagnosis of bipolar disorder and ADHD, and additional tools with higher specificity are required.

Therefore, a valid and reliable tool is needed for assessing manic symptoms in children and adolescents. Despite its weaknesses, the CMRS is a valuable tool for evaluating the severity of manic symptoms in pediatric bipolar disorder. This is beneficial for observing changes in symptoms during everyday life when using various treatment options. The development of a K-CMRS will aid Korean researchers and clinicians in providing a local language version of the validated rating scale.

Limitations to this study encompass the following. First, no cutoff value was suggested. Future research using the K-CMRS would be necessary to find a reasonable cutoff value for significant scale screening purposes. Second, our study population was small and did not include a group of healthy controls. This may have led to less precise results. Third, tests for interrater and test–retest reliability were not conducted. The addition of such tests would have further added to the validity and reliability of our research.

In conclusion, the K-CMRS is the first rating scale specifically designed to assess manic symptoms in pediatric bipolar disorder patients has been validated and adapted to the Korean language. It can easily be administered by parents, guardians, teachers, and clinicians. Its use will help measure symptom progression and the efficacy of various treatments for bipolar disorder in children and adolescents.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2023.0140.

Korean version of the Child Mania Rating Scale (K-CMRS)

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Changsu Han, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Moon-Soo Lee. Data curation: Young Eun Mok, Jeong Kyung Ko. Formal analysis: SuHyuk Chi. Investigation: Young Eun Mok, Jeong Kyung Ko. Methodology: SuHyuk Chi, Moon-Soo Lee. Project administration: Moon-Soo Lee. Supervision: Changsu Han, Mani Pavuluri, Moon-Soo Lee. Writing—original draft: SuHyuk Chi. Writing—review & editing: Moon-Soo Lee.

Funding Statement

None