Assessing Stress and Anxiety in Firefighters During the Coronavirus Disease-2019 Pandemic: A Comparative Adaptation of the Stress and Anxiety in the Viral Epidemic–9 Items and Stress and Anxiety in the Viral Epidemics–6 Items Scales

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study assessed the reliability and validity of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics–9 items (SAVE-9) and Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics–6 items (SAVE-6) scales for measuring viral anxiety among firefighters during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic.

Methods

An online survey was conducted among 304 firefighters assigned in Gyeonggi-do. The SAVE-9 scale, initially developed for healthcare workers, was adapted for firefighters. We compared it with the SAVE-6 scale designed for the general population among the firefighters sample. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to explore the factor structure of both scales. Internal consistency reliability was checked using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega. Convergent validity was assessed in accordance with the Patient Health Questionnaire–9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7 scales.

Results

The SAVE-9 scale demonstrated a Cronbach alpha of 0.880, while the SAVE-6 scale yielded an alpha of 0.874. CFA indicated good model fits for both SAVE-9 and SAVE-6 scales among firefighters sample. The SAVE-9 and SAVE-6 comparably measures viral anxiety of firefighters.

Conclusion

Both of the SAVE-9 and SAVE-6 scales are reliable and valid instruments for assessing viral anxiety among firefighters during the pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

Since the first coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan, over 600 million individuals worldwide have been diagnosed with the disease, and over 6 million infected patients died as of November 2022 [1]. As for South Korea, the number of cumulative confirmed cases exceeded 25 million in October 2022, and the total number of deaths by COVID-19 rose to over 30,000 on November 20, 2022 [2]. There have been seven significant waves of COVID-19 in South Korea until November 2022, with the most recent one still ongoing. Further, regardless of vaccine development, new variants continue to emerge worldwide, and reinfections are becoming increasingly common, making it even more challenging to control the pandemic [3].

Firefighters are among the many occupational groups largely affected by COVID-19. Primarily, they are exposed to an increased probability of viral infection because they frequently encounter the public while caring for or transporting patients [4]. This causes more stress and fear of getting infected than the general population. Furthermore, in the COVID era, the workload and burden of firefighters expanded, which led to an increased vulnerability to psychological and physical burnout. For instance, transporting patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 infection takes much longer than usual because they must be taken to hospitals where isolation rooms are available [5]. Moreover, during transportation, firefighters must take care of the patients’ health while minimizing contact, which takes significant energy. Making matters worse, if their coworkers get infected or are quarantined, the workload of remaining firefighters increases even more [6].

In recent years, there have been many efforts to understand the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of first responders, including firefighters. Between September and November 2021, 33 volunteer firefighters in the United States participated in interviews examining the effects of the pandemic on their work and individual lives [7]. The participants reported various difficulties, including fear of COVID-19 exposure and transmission, splitting of relationships, and negative impacts on their mental health. Additionally, a nationwide survey was conducted in South Korea from March 17 to April 6, 2022, during the 5th wave outbreak in the country [8]. A total of 54,056 participants, comprising 88.2% of all firefighters in the country, were enrolled. Results showed that the proportion of participants at high risk for psychiatric disorders, including posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and insomnia, significantly increased, ranging from 2% to 7%, compared to last year. In particular, the number of participants at high risk for suicide increased from 2,390 (4.4%) to 2,906 (5.4%).

However, no specific rating scale could measure firefighter’s anxiety response to the viral epidemic. We developed the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–9 items (SAVE-9) scale to assess healthcare workers’ occupation-related stress and viral anxiety in response to the epidemic [9]. We evaluated the reliability and validity of the scale among schoolteachers [10] and public workers [11], who have similar roles to healthcare workers during the pandemic, by modifying it. The primary objective of this study was to adapt the SAVE-9 scale to assess work-related stress and viral anxiety in firefighters. Moreover, as a secondary objective, this study also compares its reliability and validity to the SAVE-6 scale, previously adapted for the general population.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

The study conducted an anonymous online survey among 317 Gyeonggi-do, South Korea firefighters between October 27 and 28, 2022. The study analyzed 304 responses after excluding participants who did not complete the survey. Participants were asked to provide information about their demographic variables such as sex, age, year of employment, type of work (emergency medical service, rescue activity, office work, or fire suppression), marital status, and shift working (3-day or 21-day shift). The survey also included questions related to COVID-19, such as whether participants had experienced being quarantined due to COVID-19 infection, particularly whether they had experienced being infected with COVID-19 or received a COVID-19 vaccine. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Asan Medical Center (approval no. 2022-1293). Written informed consent for participation was waived because the participants responded voluntarily to the anonymous online survey, and we used only the responses of participants who agreed to provide their data for statistical analysis. The sample size was estimated based on the suggestion that a range of 200–300 is appropriate for factor analysis [12,13].

Rating scales

SAVE-9 scale

The primary objective of this study was to develop and validate the firefighters’ version of the SAVE-9 scale. We adapted the SAVE-9 scale, originally designed to assess healthcare workers’ work-related stress and anxiety due to the viral pandemic [9], for use among firefighters. The original SAVE-9 scale includes nine items, which can be rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0: never, 4: always). We adapted the original item 7, changing it from “After this experience, do you think you will avoid dealing with visitors with viral illnesses?” to “After this experience, do you think you will avoid dealing with clients with viral illnesses?”.

SAVE-6 scale

The secondary objective of this study was to compare the reliability and validity of the firefighters’ version of the SAVE-9 scale to those of the SAVE-6 scale. Initially, the SAVE-9 scale was divided into two factors: Factor I, anxiety response, and Factor II, work-related stress. Factor I of the SAVE-9, the SAVE-6, was reliable and valid among the general population, medical students, cancer patients, and healthcare workers [14-17]. The SAVE-6 scale includes six items that can be rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0: never, 4: always).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7

The scale is a self-reported tool for measuring generalized anxiety in individuals [18]. It comprises seven questions, each rated on a scale of 0 to 3 (0=never to 3=almost always), with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 21. A higher score indicates greater severity of generalized anxiety symptoms.

Patient Health Questionnaire–9

This is a self-reported questionnaire used to evaluate depressive symptoms [19]. It includes nine items, each rated on a scale of 0 to 3 (0=not at all to 3=nearly every day), with a total possible score ranging from 0 to 27. A higher score indicates a more severe level of depressive symptoms.

Statistical analysis

The reliability of the adapted SAVE-9 and SAVE-6 scales was checked using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega. We conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to explore the factor structure of the adapted firefighter’s version of the SAVE-9 and original SAVE-6 scales. First, skewness and kurtosis within ±2 were used to check the normality assumption for each item [20]. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values and Bartlett’s sphericity test were used to assess data suitability and sampling adequacy. A bootstrap (2,000 samples) maximum likelihood CFA was conducted as a second study to investigate the construct validity and applicability of the adapted SAVE-9 and SAVE-6 scales for assessing firefighter’s anxiety response to the viral epidemic. We defined satisfactory model fit as a standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR) value of 0.05, a root-mean-square-error of approximation (RMSEA) value of 0.10, a comparative fit index (CFI) and a Tucker Lewis index (TLI) value of 0.90 [21,22]. Multi-group CFAs were done to examine whether the adapted SAVE-9 and SAVE-6 can measure firefighter’s stress and viral anxiety in the same way across sexes (males or females), having depression (Patient Health Questionnaire–9; PHQ-9 ≥10 vs. PHQ-9 <10), or anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7; GAD-7 ≥10 vs. GAD-7 <10), or firefighters’ role. The item response theory’s graded response model (GRM) was utilized to assess the psychometric properties of the SAVE-9 and SAVE-6. In GRM, item fits were assessed through S-χ2 (p-values adjusted for false discovery rate) and RMSEA values. Next, slope and threshold parameters, threshold characteristic curves, and scale information curves were assessed. The convergent validity was checked with PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales. The IBM SPSS Windows software version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), RStudio 2023.03.0 (RStudio Inc., Boston, MA, UAS), and JASP version 0.14.1.0 software (JASP teram, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) were used for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 317 firefighters were surveyed, and 13 responses were excluded from the analysis because they were incomplete, leaving 304 responses that were analyzed. Among them, 240 (78.9%) were males, 142 (46.7%) were single, and 237 (78.0%) were shift workers. All 135 (44.4%) were on duty for fire suppression, 90 (29.6%) for emergency medical service, 63 (20.7%) on office work, and 16 (5.3%) on rescue activity. Almost all (98.0%) got vaccinated, 218 (71.7%) experienced being quarantined, and 198 (65.1%) experienced being infected (Table 1). The SAVE-9 score was significantly higher among females (21.3±6.5) than males (15.1±7.7, p<0.001). PHQ-9 and GAD-7 score also significantly higher among females (PHQ-9: 5.9±5.7, GAD-7: 3.7±4.6) than males (PHQ-9: 3.2±4.3, GAD-7: 1.8±3.3, all p<0.001).

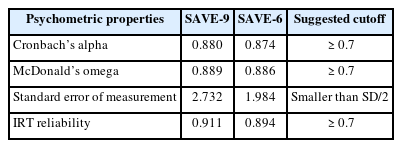

Reliability test and CFA

Table 2 shows that using skewness and kurtosis, all nine items on the SAVE-9 scale fell within the normal range. Additionally, the sampling was appropriate (KMO=0.904), and the data was suitable for statistical analysis (Bartlett’s p<0.001). The internal consistency reliability of the SAVE-6 scale (Cronbach’s alpha=0.874, McDonald’s omega=0.886) and firefighter’s version of the SAVE-9 (Cronbach’s alpha=0.880, McDonald’s omega=0.889) were shown to be good (Table 3).

Factor structure of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–6 items (SAVE-6) and firefighter’s version of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–9 items (SAVE-9)

In constructing the original SAVE-9 scale, CFA results suggested good model fits for the single-factor structure for SAVE-9 (CFI=0.999, TLI=0.999, RMSEA=0.012, and SRMR=0.047) (Table 4). The factor loadings ranged from 0.436 to 0.750 (Table 2). For the SAVE-6, CFA results also show good model fits (CFI=1.00, TLI=1.00, RMSEA=0.000, and SRMS=0.030) (Table 4). Factor loading for the SAVE-6 ranged from 0.523 to 0.778 (Table 2). Multi-group CFAs with a configural invariant model revealed that the SAVE-6 and firefighters’ version of the SAVE-9 could measure viral anxiety in the same way across sex, having depression or anxiety, or their role (Supplementary Table 1 and 2 in the online-only Data Supplement). Multi-group CFAs with metric or scalar invariant models also showed similar results.

GRM

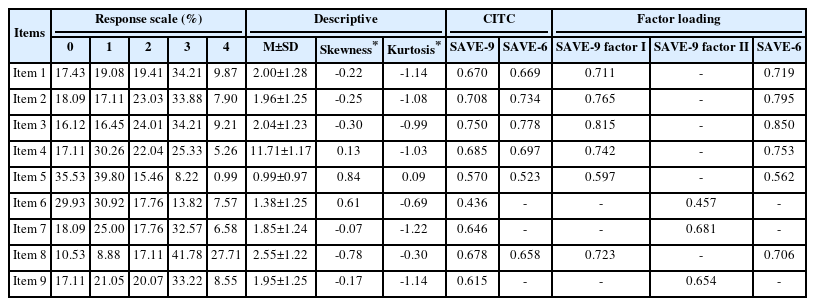

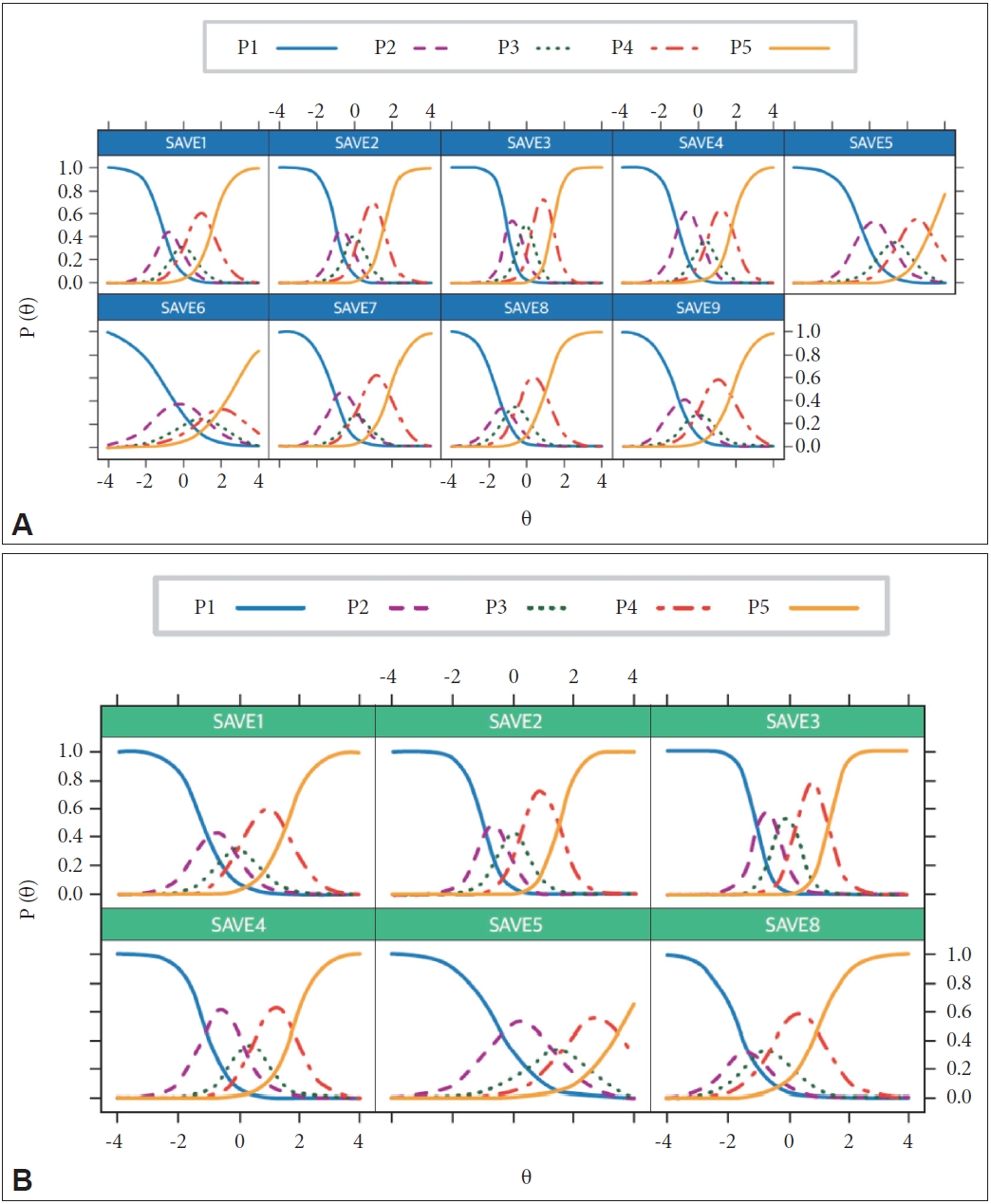

Supplementary Table 3 (in the online-only Data Supplement) demonstrates the results of item fit statistics for the SAVE-9 scale. All the items have insignificant S-χ2 (p-values adjusted for false discovery rate) and RMSEA values (<0.080), suggesting that all the items belong to respective latent constructs. Supplementary Table 3 (in the online-only Data Supplement) demonstrates the GRM outputs (slope and threshold parameters). Slope parameters show the discriminative ability of each item, and higher slope values refer to a stronger relationship to the construct of interest. Item 3 has a very low slope, item 6 has a moderate slope, and the rest have a very high slope. Slope parameters (α) range between 0.342 and 2.761 (mean α=1.836). Next, threshold coefficients can be interpreted as the difficulty parameter. A higher threshold coefficient indicates a more difficult item for the responder. About threshold coefficients (b), item 5 is the most challenging compared to other items. A higher latent trait or theta, indicating a higher ability of the responder, is required to endorse response options “sometimes” in items 5 and 6. Threshold characteristics curves for SAVE-9 (Figure 1A) show this information too. Supplementary Table 4 (in the online-only Data Supplement) shows item fits and GRM outputs for the SAVE-6. Insignificant S-χ2 (p-values adjusted for false discovery rate) and RMSEA values (<0.080) suggested that all the items belong to the respective latent construct. Item 5 has a high slope, and the rest have a very high slope. Slope parameters (α) range between 1.519 and 3.867 (mean α=2.499). Concerning threshold parameters, item 5 is the most challenging, and item 8 is the least complex compared to other items. A higher latent trait or theta is required to endorse response options “sometimes” in items 4 and 5. Threshold characteristic curves (Figure 1B) graphically depicted this information. Scale information curves (Figure 2) for both SAVE-9 and SAVE-6 show that the SAVE-9 provides more information than the SAVE-6, but not much more.

Item’s threshold curves of the firefighter's version of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–9 items (SAVE-9) (A) and the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–6 items (SAVE-6) among firefighters (B). θ refers to the latent trait, and P (θ) refers to the probability. Item 5 for SAVE-9 is shown to be the most challenging. Item 5 for SAVE-6 is shown to be the most challenging, while item 8 shows to be the least complex.

Scale information curve of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–6 items (SAVE-6) and firefighter’s version of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–9 items (SAVE-9). θ refers to the latent trait, and I (θ) refers to the information. The SAVE-9 is shown to provide more information than the SAVE-6, but not much more.

Evidence-based relations to other variables

In addition, an analysis of the convergence validity of the firefighter’s version of the SAVE-9 scale and the SAVE-6 scale with PHQ-9 and GAD-7 was conducted. The firefighter’s version of the SAVE-9 scale was significantly correlated with the PHQ-9 (r=0.346, p<0.001) and GAD-7 score (r=0.302, p<0.001). The SAVE-6 scale score was also significantly correlated with PHQ-9 (r=0.271, p<0.001) and GAD-7 (r=0.259, p<0.001).

DISCUSSION

This study observed that the SAVE-6 and single factor model of firefighter’s version of the SAVE-9 scale are reliable and valid (in both classical test theory and item response theory approaches) rating scales to assess the viral anxiety of firefighters in the COVID-19 pandemic. Initially, we developed the SAVE-9 scale to be a rating scale that can measure healthcare workers’ work-related stress and anxiety response to the viral epidemic [9]. In this COVID-19 pandemic, schoolteachers, public workers, or firefighters are forgotten frontline heroes [23] who play a similar role as healthcare workers. Hence, we wanted to develop the SAVE-9 scale according to schoolteachers, public workers, and firefighters. Our previous study evaluated the reliability and validity of the schoolteachers’ version of the SAVE-9 by adapting item 7, “Do you think you will avoid teaching children who have had viral illnesses’’ instead of “After this experience, do you think you will avoid treating patients with viral illnesses?” [10]. Our findings suggest that a single-factor model is more appropriate than a two-factor model. When examining the reliability and validity of public workers’ version of the SAVE-9 adapted from item 7 as “After this experience, do you think you will avoid dealing with visitors with viral illnesses?” a single-factor model was preferred over a two-factor model. Furthermore, we observed that the SAVE-6 scale, viral anxiety scale for the general population, is a reliable and valid rating scale for assessing public workers’ viral anxiety when compared to public workers’ version of the SAVE-9 [11]. This study also observed the single-factor model of the SAVE-9 scale was a reliable and valid rating scale for firefighters.

Initially, the SAVE-9 scale, developed for healthcare workers, was clustered into two factors, but we observed that a single-factor model of the SAVE-9 was proposed among firefighters. Several factors may have contributed to this result. First, Factor II in the original SAVE-9 scale may have been more applicable to healthcare workers than firefighters. The difference in the specific roles of each occupation can explain this. The primary role of firefighters is to transfer patients infected by COVID-19 to hospitals, whereas healthcare workers are directly involved in treating them. This may have contributed to the difference in anxiety symptoms due to the pandemic. Second, the survey in this study was conducted from October 27 to 28, 2022, more than two years after the original SAVE-9 survey (April 20 to 30, 2020). During this period, new wave outbreaks continued to emerge, and the quarantine policy, including the degree of social distancing, also changed. This may have influenced how participants responded to the items in the original scale. Third, the sampling variability, which is affected by the participants’ roles and working environments, may have contributed to the difference in the factor structure.

Based on Factor I of the original healthcare workers’ version of the SAVE-9, we developed the SAVE-6 scale, which can measure the viral anxiety of the general population [14]. Since the SAVE-9 was proposed as a single-factor model among other worker groups [10,11], we compared the reliability and validity of the single-factor model of the SAVE-9 with the SAVE-6 scale in each group. Though we did not report in the previous study [10], the SAVE-6 was reliable (Cronbach’s alpha=0.832, McDonalds’ omega=0.835) and valid (CFI=0.966, TLI=0.933, RMSEA=0.094, SRMR=0.036) among schoolteachers. We reported that SAVE-6 was a reliable and valid tool among public workers [11]. Even among healthcare workers, we reported that the SAVE-6 scale can be used with good reliability and validity [17]. The present study also observed that the SAVE-6 scale showed a good fit for the model in CFA and good convergent validity with PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales, per previous studies. Furthermore, the single-factor model of the SAVE-9 scale cannot be more informative than the SAVE-6 among this firefighters sample (Figure 2), similar to the previous study on healthcare workers [24]. According to these results, applying the SAVE-9 scale provides no more benefits than using the SAVE-6 scale. Moreover, we can apply the SAVE-6 when we need to assess the viral anxiety of workers briefly. Though the three items (items 6, 7, and 9) of the SAVE-9 can be applied to measure healthcare workers’ work-related stress in response to the viral epidemic [25], it was not more informative than the SAVE-6 and SAVE-9 [24]. Thus, these results showed that we could select a specific rating scale (SAVE-6 or each worker’s version of SAVE-9) depending on the purposes of the study.

This study has some limitations. First, females showed higher SAVE-9 scale scores than males. This is consistent with previous research conducted in Canada, in which risk factors for mental health symptoms related to COVID-19, such as depression and anxiety, were examined among public safety personnel, including firefighters [26]. According to the study, females showed significantly higher PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores than males. Furthermore, a previous study conducted by our research team, which revealed that female public workers reported substantially higher SAVE-6 scale scores than male public workers, is also in line with the current study [11]. Second, this study was conducted when we experienced approximately three years of the pandemic, and firefighters might have adjusted to the long duration of the pandemic. This might be considered when the result was interpreted. Third, we collected 304 firefighters’ responses among 7,679 (4.0%) firefighters from Gyeonggi-do and 64,054 (0.5%) from South Korea [27]. A small sample size should be considered when generalizing these results to other regions.

In conclusion, we observed that the SAVE-6 scale and the adapted version of the SAVE-9 scale for firefighters were reliable and valid rating scales for exploring the anxiety level or work-related stress of firefighters in response to viral epidemics. Further studies should validate and refine the scales in other frontline workers groups, such as police officers, paramedics, and essential service providers, to assess their viral anxiety or work-related stress during public health emergencies. Additionally, investigating the effectiveness of interventions and support systems targeted at reducing viral anxiety among frontline workers would be valuable in promoting their well-being and resilience in the face of future pandemics or similar crises.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article athttps://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2023.0260.

Measurement invariance of the firefighter’s version of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–9 items

Measurement invariance of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–6 items among firefighters

Graded response model output of the firefighter’s version of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–9 items

Graded response model output of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemic–6 items among firefighters

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Seockhoon Chung, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Inn-Kyu Cho, Jeong-Hyun Kim, Seockhoon Chung. Data curation: Inn-Kyu Cho, Han Sung Lee, Dongin Lee, Jiyoung Kim, Eulah Cho, Kayoung Song. Formal analysis: Inn-Kyu Cho, Han Sung Lee, Oli Ahmed, Seockhoon Chung, Kayoung Song. Investigation: Jeong-Hyun Kim. Methodology: Inn-Kyu Cho, Han Sung Lee, Seockhoon Chung, Kayoung Song. Project administration: Inn-Kyu Cho, Eulah Cho. Writing—original draft: Inn-Kyu Cho, Han Sung Lee, Oli Ahmed, Dongin Lee, Jiyoung Kim, Seockhoon Chung. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

This research was supported by the Development Fund of the Department of Psychiatry, Asan Medical Center (2022-004) and the Emergency Response to Disaster sites Research and Development Program funded by National Fire Agency (20013968, Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology, KEIT).