Promising Effect of the Children in Disaster: Evaluation and Recovery Intervention on Trauma Symptoms and Quality of Life for Children and Adolescents: A Controlled Study

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The Children in Disaster: Evaluation and Recovery (CIDER) program in Korea was developed to treat children and adolescents exposed to trauma. This study aimed to demonstrate the effectiveness of the CIDER through a comparison with controls.

Methods

A total of 85 participants consisted of the intervention group (n=41) and control group (n=44). We assessed the changes in trauma-related symptoms, depression, anxiety, and improvements in quality of life before and after the intervention.

Results

In total, bullying and school violence (44.7%) were the most common trauma, followed by sexual abuse (17.6%). Acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) accounted for 41.2%, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and developmental disorder were the most common comorbidities (51.8%). The symptoms of trauma, depression, anxiety, and quality of life improved significantly in the intervention group, while the control group did not show significant changes.

Conclusion

Compared with the control group, the CIDER improved symptoms and quality of life in children and adolescents who had experienced trauma. The CIDER program was practical and easy to apply, even for different ages, types of traumas, and comorbidities.

INTRODUCTION

Children and adolescents have a high risk of experiencing trauma, including domestic violence, bullying, child abuse, and many types of injury [1]. Trauma can severely impact physical and mental health in children, and its effect may persist into adulthood [2]. Significant mental health problems associated with trauma include posttraumatic stress syndrome (PTSD), depression, anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, and suicide attempts [3-5]. PTSD is a well-known psychiatric disorder in trauma-exposed children, and it consists of three main symptoms: hypervigilance, avoidance, and re-experiences [6]. PTSD has numerous adverse developmental outcomes, and children and adolescents are affected in cognitive, social, and emotional ways [1,7]. In addition, PTSD increases the risk for other mental illnesses. In the Great Smoky Mountains Study, traumaexposed children were more likely to suffer from behavior problems, depression, and anxiety than their peers (19.2%, 12.1%, and 9.8%, respectively) [8]. The impact of trauma-induced health problems and functional impairment is significant. Thus, early detection and therapeutic intervention are necessary to prevent further negative results.

Based on research, trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is the treatment of choice in trauma-exposed children [9,10]. TF-CBT reduces the trauma-related symptoms that could limit children’s emotional and social functioning [11]. In addition, it improves their adaptational skills, restoring the ordinary developmental course [12]. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is also an effective method to treat PTSD [13]. Moreover, other techniques, such as relaxation skills, mindfulness therapy, and art and play therapy, can alleviate symptoms [14-16].

Various components, such as the type of trauma, the age of the child, and the environment, impact the treatment effect [17,18]. The social and cultural background also affects treatment applications [19-22]. Furthermore, treatment feasibility is essential in clinical settings. Even if therapeutic efficacy is established, there may be barriers to therapy implementation. Depending on the features of the therapy, accessibility and economic costs may influence the choice of treatment [23]. Cultural differences in ethnicity and country also affect the widespread use of interventions [24].

To effectively treat children’s trauma-related symptoms, it is critical to establish easily applicable programs that can be implemented in clinical settings and are appropriate for each country’s culture and environment [25-27]. There is a growing interest in trauma in children and adolescents in Korea; however, there is only limited research on appropriate programs for children’s emotional and cultural knowledge [28]. Lee et al. [29] developed a “Children in Disaster: Evaluation and Recovery (CIDER)” program consisting of core contents known to treat trauma effectively. They studied the program’s efficacy. In their study, the effect of restoring daily function in children and adolescents was proven, along with a decrease in trauma symptoms [29].

The CIDER program was developed to reduce symptoms and improve adaptational function in trauma-exposed children and adolescents in Korea. The CIDER program showed a positive treatment effect in a pilot study, but it was a small sample study (n=22) and did not have a controlled design [29]. Therefore, a controlled study is required to validate the program’s effectiveness fully. The purpose of this study was to verify whether the CIDER program reduces trauma-related symptoms and improves the quality of life of children who have experienced trauma through comparison with a control group.

METHODS

Participants and procedures

A total of 90 subjects participated in this study. Among them, 42 children and adolescents participated in the CIDER program, and 48 were in the control group as a waiting list so that received no intervention during the study. A total of five participants (5.6%) dropped out of the study, one from the intervention group (2.4%) and four from the control group (8.3%). The final analysis was conducted on 85 subjects (41 in the intervention group and 44 in the control group). The participants were recruited from seven institutions (two alternative schools where the psychiatrist is a principal, three psychiatric clinics, and two counselling centers for trauma victims). We recruited children and adolescents who had experienced trauma. Participants had to be under age 18 and understand and respond to the questionnaire. A high risk of suicide, psychotic symptoms, such as hallucinations or delusions, and severe symptoms of dissociation were considered exclusion criteria. Participants in our study were taking medications simultaneously. The drug’s type and dosage remained unchanged during the program. Adolescents and parents provided informed consent/assent and participated in the assessment. All participants completed questionnaires to assess their symptoms and quality of life at the end of the session. The study procedures were approved by the Eulji University Hospital’s Institutional Review Board (IRB No. EMCS 2015-05-021-006). This trial has been registered with cris.nih.go.kr (registration number: KCT0004681).

CIDER program

The CIDER consists of eight 50-minute group sessions. The CIDER program was based on TF-CBT, EDMR, emotional freedom techniques (EFT), image rehearsal therapy, and mindfulness therapy [30-34]. The CIDER program takes 4–6 weeks to complete. In this study, the CIDER program was implemented as a school-based and clinic-based approach and was conducted in alternative schools, clinics, and counselling centers.

The first session is dedicated to psychoeducation (understanding the brain and psychological symptoms) and introduces the treatment. Relaxation techniques are presented in the second session. The third session provides an opportunity to understand the memory better. EFT and mindfulness techniques were the focus of the fourth session. During the fifth session, cognitive reappraisal was practiced. Participants worked on imaginal exposure in the sixth session. The seventh session focused on modifying and controlling repetitive uncomfortable dreams and memories through repeated imagery. During the closing session, participants reviewed the process and content of the program, imagined their desired future state, and enhanced their understanding of change and growth. The program’s details are available in a previously published paper [29].

Measures

In this study, we evaluated the trauma symptoms, anxiety, depression, and stress levels. To assess the trauma symptoms, the Korean version of the Children’s Response to Traumatic Events Scale-Revised (K-CRTES-R) was conducted [35]. The KCRTES-R is a 23-item questionnaire designed to assess intrusion, avoidance, and arousal based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-4th Edition (DSMIV) [8,22]. The questionnaire explores traumatic symptoms from the previous seven days and measures them on a four-point Likert scale. It takes 5–10 minutes to complete the questionnaire, and the overall score ranges from 0–115 [36].

Depending on the child’s age, the measure of depression was either the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI) [29,34] or the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). The BDI is one of the most widely used self-report inventories for depression [37], and it consists of 21 questions about how the subject felt during the past week [38]. The total score is compared to determine the depression severity [39]. The CDI is a self-rated, symptom-oriented 27-item scale.

State anxiety implies a temporary state of anxiety caused by the arousal of the autonomic nervous system in a specific situation. The State Anxiety Inventory for Children (SAIC) was used to assess the child’s state anxiety level. It was initially derived from Spielberger’s adult state anxiety inventory [40] and modified for children. The scale consists of 20 questions in total. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) is a method used to determine the quality of life of children in the healthcare setting according to the self-report of the child or the assessment provided by the caregiver [41,42]. It comprises four physical, emotional, social, and school functioning domains. A higher score means better quality of life.

The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) [43] score is the sum of several types of abuse, neglect, and other signs of a difficult childhood. According to the ACE Study, a higher ACE score indicated more negative experiences during childhood. A high ACE score also means an increased risk of developing health problems in the future [43]. In a questionnaire assessing children’s and adolescents’ stress, there were a total of 36 questions. A high score means high stress.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The demographics of the participants were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Changes in the trauma symptoms, depression, anxiety, and quality of life from pre- to post test were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. To analyze the influence of traumatic symptoms, we calculated the mean reduction in the K-CRTES-R score before and after the program. According to the median value of the reduced score, the intervention group was divided into larger and smaller reduction groups. Regression analysis was performed in the study of the treatment effect. A p-value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance.

RESULTS

Demographic data of the participants

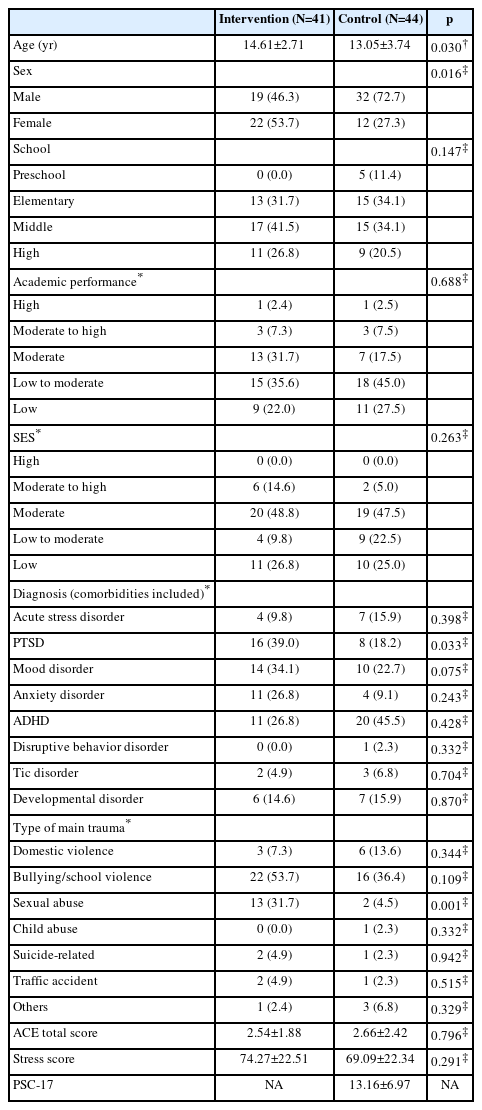

A total of 85 subjects were analyzed in the study (41 subjects in the intervention program, 44 subjects in the control group). The average age of the children who participated in the intervention group was 14.61 (±2.71) years old, with a total of 19 boys (46.3%) and 22 girls (53.7%). In the control group, the average age was 13.05 (±3.74) years old, 32 boys (72.7%) and 12 girls (27.3%), respectively. There was a significant difference in age between the two groups (p=0.030), and there were significantly more girls in the intervention group (p=0.016). The intervention group recruited 54.5% of participants from the support center for sexual violence victims and 34.1% from the university hospital.

According to the subjective assessment of academic performance, 35.6% of participants in the intervention group and 45.0% of those in the control group were in the low to moderate group. The intervention group had 48.8% moderate SES, and the control group had 47.5% moderate SES. Regarding the diagnosis, the intervention group had PTSD (39.0%), mood disorder (34.1%), anxiety disorder (26.8%), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (26.8%), developmental disorder (14.6%), acute stress disorder (9.8%), and tic disorder (4.9%). In the control group, there were acute stress disorders (15.9%), PTSD (18.2%), mood disorder (22.7%), anxiety disorder (9.1%), ADHD (45.5%), tic disorder (6.8%), and developmental disorder (15.9%). According to the primary trauma patterns, bullying and school violence (53.7%) were the most common, followed by sexual abuse (31.7%) in the intervention group. Additionally, bullying and school violence (36.4%) were most common in the control group, followed by domestic violence (13.6%). The rates of PTSD (p=0.033) and sexual abuse (p=0.001) were higher in the intervention group.

The total ACE score was 2.54 (±1.88) in the intervention group and 2.66 (±2.42) in the control group, with no significant difference (p=0.796). The stress score was 74.27 (±22.51) for the intervention group and 69.09 (±22.34) for the control group (p=0.291). The pediatric symptom checklist-17 (PSC-17) scale was applied only in the control group, and the total score was 13.16 (±6.97). Details are shown in Table 1.

The treatment effect of the CIDER program

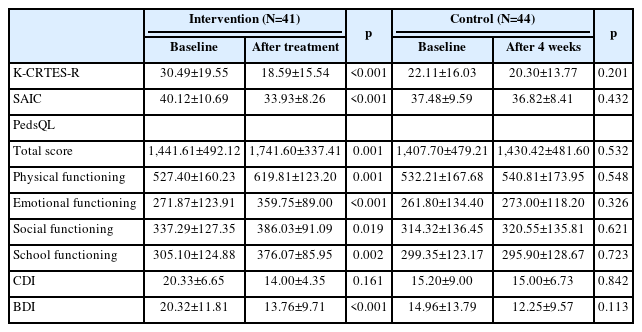

The CIDER group was evaluated for changes in the trauma symptom scores before and after the intervention, and the control group was assessed four weeks from the baseline assessment. In the intervention group, the K-CRTES-R score decreased from 30.49 (±19.55) to 18.59 (±15.54) (p<0.001), while the control group showed no change from 22.11 (±16.03) to 20.30 (±13.77) (p=0.201). The scale of depression and anxiety changed significantly in the intervention group. The SAIC decreased from 40.12 (±10.69) to 33.93 (±8.26) (p<0.001), while the control group changed from 37.48 (±9.59) to 36.82 (±8.41) (p=0.432). BDI also changed from 20.32 (±11.81) to 13.76 (±9.71) (p<0.001), while the control group showed no change (p=0.113). The PedsQL scale significantly increased from 1,441.61 (±492.12) to 1,741.60 (±337.41) (p=0.001) in the intervention group. However, the control group did not show significant differences after four weeks on any scale (p>0.05). Results are shown in Table 2.

We conducted subgroup analysis according to the intervention settings. We divided the sample into school-based (n=37) and clinic-based (n=53) approaches. In both approaches, the intervention group showed statistically significant differences in trauma-related symptoms and the level of PedsQL compared to the control group. Details are shown in Supplementary Table 1 (in the online-only Data Supplement).

The influence of baseline K-CRTES-R

The mean reduction in the K-CRTES-R score before and after the program was -11.90 (±12.11). The median value of the reduced scores was -12 points. According to the median value of the reduced score, the intervention group was divided into larger (n=22, 53.7%) and smaller reduction groups (n=19, 46.3%). The average reduction for the larger reduction group was -21.50 (±6.53) points, and that for the smaller reduction group was -1.31 (±7.45) points (p<0.001). The group with larger symptom reduction had higher baseline K-CRTESR scores (p<0.001), higher stress scores (p=0.029), and lower levels of emotional functioning in PedsQL (p=0.018). The baseline depression, anxiety, and quality of life measures were not statistically significant in predicting better outcomes in logistic regression analysis. However, a higher baseline KCRTES-R score was related to a better effect after treatment (R2=0.404, p=0.015). Details are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to show the efficacy of a structured CIDER program in reducing trauma symptoms. Trauma symptoms, depression, anxiety, and quality of life significantly improved in the treatment group compared to the control group, and the dropout rate was low. These findings demonstrate promising results for treating children and adolescents with trauma and comorbidities. The CIDER program effectively reduced symptoms in various age groups and types of traumas, proving its efficacy and feasibility.

The CIDER program improved the trauma symptoms assessed by the K-CRTES-R, while the control group showed no change. The CIDER program’s overall composition was designed to reduce trauma symptoms. The primary components were emotional regulation, stress management, coping skills enhancement, and repeated psychoeducation and relaxation techniques, all of which affected symptom reduction [29]. In the previous pilot study of the CIDER, the K-CRTES-R score also decreased from 20.68 (±16.78) to 10.77 (±11.96). In the present controlled study, the baseline K-CRTES-R score was higher than that in the pilot study and decreased from 30.49 (±19.55) to 18.59 (±15.54). This study demonstrated reduced trauma-related symptoms in line with previous TFCBT research [44,45].

This study compared the degree of trauma symptom reduction by the K-CRTES-R score. The group with larger decreases in trauma symptoms had higher baseline K-CRTES-R scores, higher stress scores, and low emotional functioning. Thus, the group with severe symptoms showed greater improvement. In our study, the baseline severity of the K-CRTES-R score influenced the symptom reduction. Previous studies reported contradictory findings regarding relationships between baseline symptom severity and outcome. Most previous studies have shown that treatment is effective when symptoms are mild. Mild symptoms and minor trauma impact rapid therapeutic results [46], and higher pretreatment posttraumatic stress symptoms characterize nonresponders [44,45]. Lower pretreatment depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms and fewer trauma types were related to the child- and parent-reported responder status [46]. Previous research has found that the dropout rate is high when trauma symptoms are severe, and the treatment effect is limited due to avoidance symptoms [47]. However, the CIDER program demonstrated the possibility of efficacy with a low dropout rate even in cases of individuals with relatively more symptoms. It is likely that the CIDER program did not stimulate the participants’ avoidance symptoms. Since the program consists of content that can comfortably control emotions, it may be more effective when symptoms are relatively severe. Considering that the maximum K-CRTES-R score was 111, the CIDER participants’ scores ranged from 30 to 50, indicating relatively mild to moderate symptoms. According to the characteristics of the group, the overall severity may not be high, even though there are many symptoms of trauma. Further research on the factors affecting symptom reduction is needed to predict the treatment outcome and reflect it in the program.

Depression and anxiety symptoms decreased after the CIDER program in this study. In the CIDER pilot study, depression was reduced, but anxiety was not significantly reduced. Previous research has established a strong correlation between depressive mood and trauma-related symptoms [48,49]. The CIDER program effectively reduced negative emotions and enhanced positive emotions [29]. The CIDER program consisted of exercise the relaxation techniques. In addition, CIDER focused on modifying and controlling repetitive uncomfortable dreams or memories. We could identify that these skills reduced the anxiety symptoms among the participants exposed to traumatic events [29]. A similar concept can explain anxiety improvement. Another study discovered reductions in anxiety and depression and a decrease in trauma symptoms [50]. Moreover, Thornback and Muller [51] emphasized that emotion regulation is a worthy intervention target for traumatized children.

CIDER has improved the participants’ quality of life in several areas. It is particularly encouraging, as it demonstrated considerable improvement in all domains, including physical, social, school, and emotional functioning recovery. Our study showed similar results to previous research [52]. Adolescents exposed to traumatic experiences have been shown to have considerably reduced quality of life outcomes [53], and they recovered after this intervention. According to our findings, a better quality of life may have resulted from reduced trauma symptoms, depression, and anxiety. Our study shows that symptom improvement is linked to functional recovery and improvements in the quality of life. In addition to assessing symptoms and the quality of life immediately following treatment, more research is required to see if the effect lasts for an extended period.

Our study population included individuals with a wide range of different types of trauma and symptom manifestations, as well as a significant proportion of children with comorbidities. The intervention in the CIDER was significantly effective in children with comorbidities such as ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Based on previous research, children with ADHD or developmental disorders are more likely to be exposed to school violence, which can have detrimental emotional and psychological consequences [54-56]. School violence and bullying accounted for the most considerable portion of participants in the current study. Children exposed to school violence develop PTSD, depression, anxiety, a variety of physical problems, and difficulties adapting to school [57,58], which can persist into adulthood [54]. The higher rate of school violence in our study may be due to the high prevalence of ADHD and developmental disorders among the children’s underlying diagnoses [55,56]. Children with developmental disorders frequently experience trauma due to school violence [59,60]. A systematic review of youth with ASD showed school bullying and victimization prevalence rates of 10% and 16%, respectively [59]. ADHD was linked to both bullying other students (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.8, 95% CI [confidence interval] 2.0–7.2) and being bullied (OR: 10.8; 95% CI 4.0–29.0) [61]. The CIDER program can be effectively applied to children with comorbidities.

The dropout rate (2.38%) of children who participated in the CIDER program was relatively low compared to other studies. According to a recent review, the dropout rate from psychosocial therapy for PTSD in children was 11.7% (95% CI 8.2–14.6) [62]. The supportive approach of caregivers in the current study may have impacted the low dropout rate. Even though the caregivers were not direct participants in the CIDER program, primary trauma-related education and a supportive approach were delivered. This component probably influenced the outcomes. Clearly, the dropout rate increased if the caregiver avoided interventions or if the child assumed that the parents did not approve the therapy [63]. It is highly probable that a stable environment increased access to treatment and positively affected the formation of a treatment relationship [47]. Treatment with support in a rapport-building atmosphere would have also reduced avoidance and decreased dropout. Yasinski et al. [64] emphasized that therapeutic relationships predict treatment discontinuation. Nevertheless, it is possible that other unmeasured or contextual factors, potential confounding factors could also be influencing the dropout rate. Therefore, we need to consider these factors carefully interpreting the low dropout rates.

The CIDER program effectively reduces the symptoms of several types of traumas. In particular, the CIDER program can be helpful when children with ADHD or developmental disorders are exposed to school violence. It offers the advantage of administering treatment in various settings, including clinics, schools, and counselling centers. Previous research has indicated that interventions among children and adolescents are beneficial and feasible in real life when school-based and clinic-based programs are implemented [65]. Furthermore, in light of recent evidence indicating that therapists should provide additional attention to children with cognitive impairment or learning disabilities [66], the CIDER program can be advantageous even in children and adolescents with developmental disorders.

The CIDER program consists of several parts of proven treatments. Even though TF-CBT and EMDR are effective treatments, they might be challenging to implement depending on the situation. EMDR requires specialized training, while TF-CBT is similarly susceptible to environmental factors. It is challenging to conduct organized programs in some circumstances. The CIDER program consists of easy-to-execute parts, which may be widely applicable to children in various settings.

Given earlier research suggesting the importance of cultural considerations [67], acceptability and adaptability are vital components in any program [68]. Language and ethnic background can also have an impact on treatment adherence. In one study, compared to Latino children of Spanish-speaking origin, African-American children received considerably shorter therapy durations and experienced greater rates of premature termination [69]. These findings imply that the patient’s social and cultural context influences treatment adherence. The CIDER program has a significant effect and can be helpful regardless of trauma type, participants’ age, and comorbidities. The development of the CIDER program will be a worthwhile attempt for future applications in diverse contexts.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the number of children who participated was relatively small, and the study was not randomized. There were also limitations in assessing information such as medications. The two groups differed in terms of age and sex. However, the age gap was not large. More girls were in the intervention group (53.7%). In several trauma intervention studies, the proportion of girls among participants tended to be higher, 65%–87% [50,70]. Additionally, the rates of sexual abuse and PTSD were higher in the intervention group. A support center for victims of sexual violence recruited the subjects who participated in CIDER, and it seems that they had an impact on a higher prevalence of PTSD. Otherwise, there was no difference in the degree of trauma symptoms between the intervention group and the control group; therefore, it is considered that there is little effect on the interpretation of the results. We could not survey the period from the occurrence of events to the CIDER intervention. Since the time after the traumatic events may also affect the trauma symptoms and severity of children and adolescents, it is necessary to apply strategies and specifically intervene according to the period after the trauma. The types of institutions, ages, diagnoses, and trauma types in the study differed. It is necessary to consider these limitations when interpreting the results. However, even with different ages and diagnoses, it is expected that this program will be effective for children and adolescents with trauma experiences. Extensive cohort studies are needed to confirm the program’s effectiveness in future studies.

Conclusion

The CIDER program was developed by combining and modifying the core elements of many treatments for trauma. The CIDER program, which consists of critical factors that can be easily applied, could have high feasibility. In this research, the 8-session program showed treatment efficacy and improved quality of life among children and adolescents who experienced trauma compared to the control groups. Although there are many different types of traumas, the treatment program’s effectiveness has been verified. This program can be effective regardless of the type of trauma, the child’s age, comorbidities, and the treatment setting.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article athttps://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2023.0202.

Subgroup analysis of the changes in trauma, depression, anxiety symptoms and quality of life

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Mi-Sun Lee, Soo-Young Bhang. Data curation: Eun Jin Park, Seung Min Bae, Hyun Soo Kim, Minha Hong, Eunji Kim, Seul Ki Lee, Jiyoun Kim. Formal analysis: Eun Jin Park, Mi-Sun Lee. Funding acquisition: Soo-Young Bhang. Investigation: Soo-Young Bhang. Methodology: Mi-Sun Lee, Seung Min Bae, Eunji Kim, Jiyoun Kim, Soo-Young Bhang. Project administration: Soo-Young Bhang. Resources: Eun Jin Park, Seung Min Bae, Hyun Soo Kim, Minha Hong, Eunji Kim, Seul Ki Lee, Jiyoun Kim. Software: Mi-Sun Lee, Eun Jin Park. Supervision: Hyun Soo Kim, Soo-Young Bhang. Validation: Eun Jin Park, Mi-Sun Lee. Visualization: Mi-Sun Lee. Writing—original draft: Eun Jin Park, Mi-Sun Lee. Writing— review & editing: Mi-Sun Lee, Eun Jin Park, Soo-Young Bhang.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by a grant from the Korean Mental Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HM15C1058).