Characteristics of Comorbid Physical Disease in Patients With Severe Mental Illness in South Korea: A Nationwide Population-Based Study (2014-2019)

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to identify the associations of chronic physical disease between patients with severe mental illness (SMI) and the general population of South Korea.

Methods

This study was conducted with National Health Insurance Corporation data from 2014 to 2019. A total of 848,058 people were diagnosed with SMI in this period, and the same number of controls were established by matching by sex and age. A descriptive analysis was conducted on the sociodemographic characteristics of patients with SMI. Conditional logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the associations between comorbid physical disease in patients with SMI and those of the general population. SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC, USA) were used to perform all statistical tests.

Results

The analysis revealed significant differences in medical insurance, income level, and Charlson Comorbidity Index weighted by chronic physical disease, between patients with SMI and the general population. Conditional logistic regression analysis between the two groups also revealed significant differences in eight chronic physical diseases except hypertensive disease.

Conclusion

This study confirmed the vulnerability of patients with SMI to chronic physical diseases and we were able to identify chronic physical disease that were highly related to patients with SMI.

INTRODUCTION

The World Health Organization defined health, in 1948, as follows: health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. If we are not physically and mentally healthy, we are more likely to lead an unhealthy life, and are more likely to die at an earlier age than the average. Thus, it is important to manage physical and mental health simultaneously.

The pathways leading comorbidity of mental and physical illness are complex and bidirectional [1]. In other words, having a severe mental illness (SMI) can be a risk factor for developing a chronic physical disease and vice versa [2-4]. Many researchers have been conducting study to understand the association between SMI and physical disease [1-18]. In a 2019 Lancet Psychiatry Commission [19], it identified 30 systematic reviews of physical disease in patients with SMI, 18 of which were on cardiometabolic disorders. In 2020, Denmark looked at the association between SMI and subsequent medical conditions and announced results showing that people with SMI have higher risk of developing specific medical conditions in the future than the general population [2]. However, in 2020, Dr. Amy Ronaldson’s research team at King’s College London conducted a study into the causal relationship between physical multimorbidity patterns and common mental health disorder using data formats from 154,367 middle-aged adults aged 40 to 69 registered in the UK Biobank [4]. Physical multimorbidity was defined as a case of having two or more chronic physical disease that lasted for at least three months. As a result, middle-aged adults with physical multimorbidity status were more likely to experience depression and anxiety later in life. Afterwards, in 2020, a study was conducted in the UK on the temporal relationship between SMI and chronic physical comorbidity [3]. In this cohort study, it aimed to determine the cumulative prevalence of 24 chronic physical conditions in people with SMI form 5 years before to 5 years after their diagnosis from 2000 to 2018, it was confirmed that the probability of developing chronic physical comorbidity increased over time for each subtype of SMI. Likewise, several studies have suggested that there is a link between SMI and chronic physical disease, and that they influence each other. Therefore, it shows that causality goes both ways.

In addition, there are many studies investigating that chronic physical disease cause earlier mortality among individuals with SMI [20-26]. The mortality rate of people with SMI has been known to be higher than that of the general population. According to various studies, patients with SMI die about 10–20 years earlier than the general population [21,26,27]. Moreover, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses [23,26,28-31] showed that the mortality rate of people with SMI is two to three times higher than that of the general population. Considering these results, the physical problems of patients with SMI may ultimately affect the quality of life and the prognosis or the disease regardless of the prior order of chronic physical and mental illness.

Compared to theses research achievements in other countries, there has not been much research on SMI and physical disease comorbidity in South Korea. As far as we are aware, studies on the association between SMI and chronic physical disease in South Korea have not been clear so for, but research efforts on the chronic physical disease of patients with SMI in South Korea are beginning. In a survey conducted through Korean Epidemiologic Catchment Area study replication (KECA-R) from 2006 to 2007, subjects with any mental disorder showed significantly higher prevalence of chronic physical conditions and medical risk factors [11]. This study was the first identification of significant mental-physical comorbidity in the general Korean population, but the limitation was that it was not a total population survey. In 2022, a study was conducted to examine the odds ratios of comorbidities in psychiatric and physical diagnoses through the demographic information and medical records of on million people using the National Health Insurance System dataset provided by the Korean government [6]. In total, 7.6% were diagnosed with mental illness, the number of physical diagnoses among them was 11.2%, which was 1.6 times higher than non-psychiatric people.

Based on these results, we conducted this study to examine the characteristics of chronic physical disease associated patients with SMI among all mental illness. Therefore, this study had three objectives. First, we attempted to examine the characteristics of all patients with SMI over a longer period of time (2014–2019), unlike previous studies. Second, we investigated which chronic physical diseases have commonly in people with SMI in South Korea. Finally, we compared the chronic physical diseases having in SMI patients with those of the general population.

METHODS

Study population

This study was performed by the Seoul Mental Health Welfare Center, an affiliate of the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare, operated by the Seoul Medical Center. We obtained National Health Insurance Corporation (NHIC) data from 2014–2019 to study the characteristics of people with mental illness living in South Korea. The categoriesdefined based on the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s disability diagnosis criteria for patients with SMI are F20–29, F30, F31, F32.3, and F33. Patients with SMI are defined as people diagnosed with F20–29 (schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders), F30 (manic episode), F31 (bipolar affective disorder), F32.3 (severe depressive episode with psychotic symptoms), and F33 (recurrent depressive disorder) in the International Classification of Disease-10 (ICD-10). Therefore, we defined patients with SMI as those who were diagnosed with F20–29, F30, F31, F32.3, and F33, and visited the hospital at least once from 2014 to 2019. The general population was the control group, adjusted for sex and age, to compare the physical characteristics of people with SMI.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 2020-06-006-002) of Seoul Medical Center. Informed consent was waived by the IRB because we obtained anonymous, de-identified data from the NHIC.

Study methods

We requested data from the full medical records from 2014 to 2019 in the National Health Information Database’ through the NHIC’s national data application, review, and approval process. From this database the Qualification and Medical Details databases were analyzed. The Qualification database contains information on individual insurance qualification and insurance premiums. The medical details database contains the details of individuals visiting medical institutions and receiving medical treatment, and the details of the charged expenses.

First, we selected patients with SMI (F20–29, F30, F31, F32.3, F33) who met the criteria of the Ministry of Health and Welfare for mental illness. From 2014 to 2019, a total of 842,459 people met this definition. We studied the sociodemographic characteristics of patients with SMI who visited the hospital more than once with any of the above diagnoses. Sociodemographic factors, identified through the NHIC, included sex, age, type of medical insurance, income level, and physical disease.

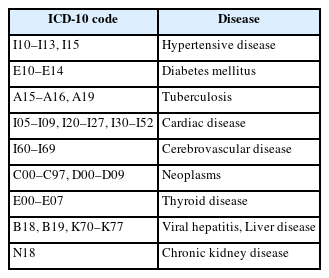

Next, we compared the types and number of physical comorbidities in patients with SMI. Physical diseases were divided into nine categories (Table 1), excluding mental and behavioral disorders, among 10 chronic physical diseases determined by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in the ‘Korea Standard Classification of Disease.’ Chronic physical disease was defined as ‘treatment three or more times for the nine diseases (Table 1) in a year.’ We compared not only the proportion of people with chronic disease comorbidities among patients with SMI, but also how they differed from those of the general population. We used the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) to classify the severity of the physical diseases for comparison of physical disease in patients with SMI and the general population.

Statistical analysis

Through this study, we tried to examine the sociodemographic characteristics of patients with SMI and how their physical comorbidities changed. In addition, we assessed whether the characteristics of the physical comorbidities different between the general population and patients with SMI, and whether the differences were significant.

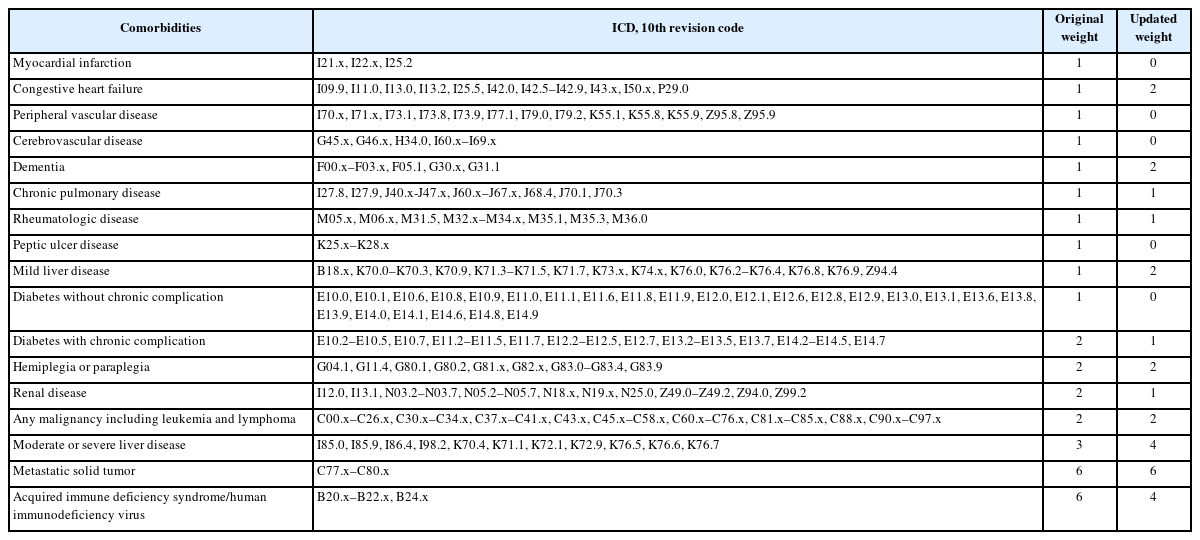

A descriptive analysis was conducted to examine the sociodemographic characteristics of patients with SMI and the general population from 2014 to 2019. We compared sex, age, type of medical insurance, income level, and severity of physical comorbidities. Most of the studies using health insurance claim data are observational studies, and selection bias and confounding factors may occur in these studies. Therefore, severity correction to minimize such bias is essential. Although comorbid physical disease is not related to the main diagnosis of mental disease, the comparison is necessary, by revising the severity, in that it increases complications, mortality, length of stay, and medical expenses. In most domestic studies using health insurance data comprehensive measurement tools, such as the CCI and Elixhauser’s comorbidity measure (ECM), are mainly used as correction methods for comorbidities. The CCI is the most widely used comorbidity measurement tool for administrative data and was used in this study. The CCI was developed on medical record data converted to ICD-10 codes for application to administrative data, and finally 17 disease groups were presented (Table 2). Therefore, after correcting by assigning weights to comorbidities of patients with SMI through CCI, comparative analysis was conducted with the data of the general population [32].

In this retrospective study, a case-control design was applied to examine the characteristics of chronic physical disease in patients with SMI and in the general population. First, significant differences in nine chronic physical diseases between patients with SMI and the general population were compared. Significant differences in the number of chronic physical diseases were also analyzed. To determine the differences in the relevance of chronic physical diseases between patients with SMI and the general population, we estimated odds ratios (ORs) and two-tailed 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using conditional logistic regression models for matched case-control pairs. A comparative analysis between the two groups was performed in both the crude model and the adjusted model. In the case of the adjusted model analysis, it was performed after correcting for sex, age, medical insurance, income level, and CCI, which were significant in the descriptive analysis.

SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC, USA) were used to perform all statistical tests.

RESULTS

From 2014 to 2019, a total of 848,058 people with SMI were selected. Of the total, 335,633 patients were diagnosed with F20–29; 227,202 with F30–31; and 285,223 with F32.3–33. The results are as follows.

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients with SMI and the general population

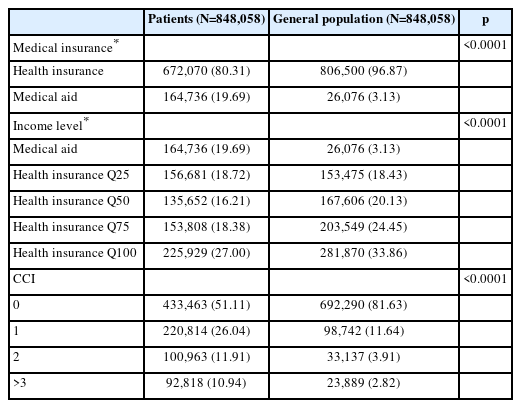

The sociodemographic characteristics of patients with SMI and the control group are shown in Table 3. Of the total 848,058 patients, 350,040 (41.28%) were male and 498,018 (58.72%) were female. Those aged 50–59 accounted for the largest proportion of the total. Among patients with SMI, 164,736 were on medical aid, accounting for 19.69% of the total, about six times higher than the general population’s 3.13%. In addition, the number of patients with SMI with one or more chronic physical diseases was 519,493 (61.26%) in Table 4. This was also higher than the 47.89% of the general population. As a result of the comparison with the control group, medical insurance, income level, and CCI, among the sociodemographic characteristics, excluding adjusted sex and age, were significantly different between the patients with SMI and the general population.

Comorbid physical diseases of patients with SMI and the general population

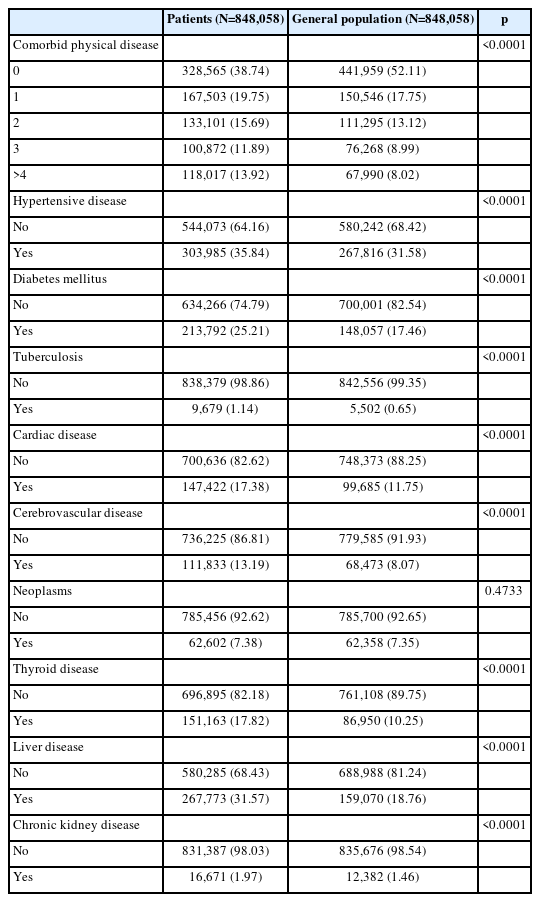

We analyzed the comorbid physical diseases of the general population and patients with SMI (Table 4). In patients with SMI, hypertensive disease was the most common chronic physical disease at 35.84%, followed by liver disease at 31.57%, and diabetes mellitus at 25.21%. In the general population, the ranking of chronic physical diseases was similar to that of patients with SMI, but there was a significant difference in the ratio. In the general population, hypertensive disease was the highest at 31.58%, followed by liver disease at 18.76%, and diabetes mellitus at 17.46%. The comparison of the comorbid chronic physical diseases of patients with SMI and those of the general population revealed significant differences in the occurrence of eight chronic physical disease except neoplasm.

Number of comorbid physical diseases in patients with SMI and the general population

There was also a difference in the number of comorbid chronic physical diseases occurring in patients with SMI and the general population (Table 4). In the general population, there were 441,959 cases without any physical diseases (52.11%), but in patients with SMI, the number and percentage were 328,565 and 38.74%, which was significantly lower than that of the general population. The difference between the two groups was also evident in the number of people with four or more comorbid chronic physical diseases. The number in patients with SMI was 118,017 and 13.92%, higher than that in the general population of 67,990 and 8.02%. There was a statistically significant difference in the number of comorbid chronic physical diseases between patients with SMI and the general population.

Differences in comorbid physical disease in patients with SMI and the general population

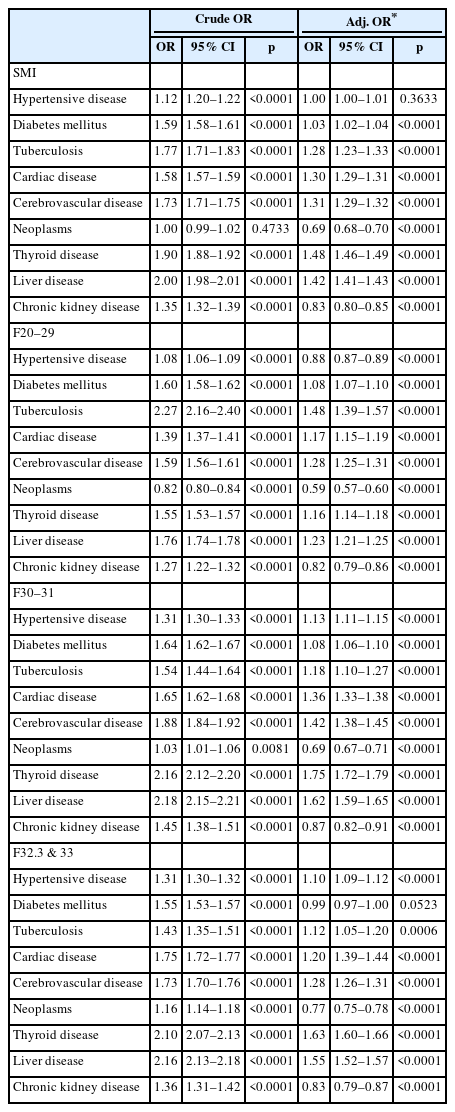

There was a significant difference in the comorbid chronic physical diseases between patients with SMI and the general population, so the odds ratios between these two groups were analyzed (Table 5). There were significant differences in eight chronic physical diseases except neoplasms, of which the crude OR of liver disease (OR=2.00, 95% CI 1.98–2.01), was the highest, followed by thyroid disease (OR=1.90, 95% CI 1.88–1.92). The results after adjusting were slightly different. Thyroid disease was also the highest at 1.48 and liver disease followed at 1.42 for adjusted ORs, which was analyzed after correcting for sex, age, health insurance, income level, and CCI variables, which had significant differences in relation to sociodemographic factors.

Differences in comorbid physical disease between a specific mental illness and the general population

From 2015 to 2019, significant differences and the OR of chronic physical diseases between all patients with SMI and the general population were examined. However, SMI is largely divided into three groups (F20–29/F30–31/F32.3, F33), and the disease characteristics and types of drugs used for treatment after diagnosis change, so it is necessary to study each disease group separately. In this study, patients with SMI (F20–29), which is mainly related to psychotic symptoms, showed higher adjusted ORs (OR=1.48, 95% CI 1.39–1.57) for tuberculosis than those in the general population, followed by cerebrovascular disease (OR=1.28, 95% CI 1.25–1.31), and liver disease (OR=1.23, 95% CI 1.21–1.25) (Table 5). In patients with SMI with bipolar disorder, similar to the whole, thyroid disease showed the highest OR (OR=1.75, 95% CI 1.72–1.79), followed by liver disease (OR=1.62, 95% CI 1.59–1.65) (Table 5). Finally, in the case of patients with SMI diagnosed with depression, thyroid disease was the highest (OR=1.63, 95% CI 1.52–1.57), followed by liver disease (OR=1.55, 95% CI 1.52–1.57) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

From 2014 to 2019, patients with SMI received more medical aid than the general population, and the rate of having at least one physical disease was found to be higher than that of the general population. Although the exact causal relationship could not be derived in this study, it was confirmed that the socioeconomic status and physical health of patients with SMI were poorer than that of the general population. What is more noteworthy in this paper is the frequency of occurring chronic physical diseases between patients with SMI and general population. The proportion of one or more chronic physical diseases was 61.26% for those with SMI, whereas it was much lower at 47.89% for the general population, and this difference was significant. Additionally, as the number of chronic diseases increased, the difference in frequency between patients with SMI and the general population increased significantly. The proportion of severely mentally ill patients with four or more chronic physical diseases was found to be almost twice as high as that of the general population. In view of these differences, there is a clear connection between SMI and chronic physical disease. This was also seen when the government divided into nine groups defined as chronic physical disease for chronic disease management. When examining the difference among nine chronic physical diseases between patients with SMI and the general population after adjusting all variables that could the results, eight chronic physical diseases except hypertensive disease showed significance.

In the case of SMI diagnosed as F20–29, tuberculosis was the most correlated chronic physical disease compared to the general population. According to the systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted by the Lancet psychiatric commission in 2019, patients with schizophrenia mainly have physical problems such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, and rheumatoid arthritis [19]. This was slightly different from the results of a study of SMI in South Korea. In this study, diagnoses of F20–29 showed the highest association with tuberculosis, followed by cerebrovascular, and liver disease. However, several studies have consistently shown a higher incidence of tuberculosis among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population [33-36]. In addition, according to a recent systematic review, there was a strong cohort study result in Asia which showed that patients with schizophrenia have a higher possibility of having active tuberculosis. According to the results, schizophrenia increases the risk of active tuberculosis, ranging from hazard ratio=1.52 (95% CI 1.29–1.79) to risk ratio=3.04 [37,38]. Considering that these results are from an Asian cohort study, it is likely that the risk of tuberculosis itself is higher in Asia, consistent with the results of this study.

Diagnoses of F30–31, F32.3, and F33, were found to correlate more with chronic physical diseases, such as thyroid and liver disease, than those of the general population. According to a study conducted by the Lancet psychiatric commission [19], bipolar disorder and depression are associated with chronic physical diseases such as asthma, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and obesity. In the case of depressed patients, cancer and Parkinson’s disease were also found to be associated [19]. The results of that study were consistent with some of the results of this study, but not all. In this study, as shown in Tables 5, there was a significant correlation with eight chronic physical diseases except hypertensive disease. However, thyroid and liver disease were highly correlated among them. Several papers have reported on the relationship between depressive or bipolar disorder and thyroid problems [16,39,40]. Previously, the relationship between mood disorders and thyroid hormones was the main study subject, but a study published in 2019 found that depressive and bipolar disorder are also related to thyroid autoimmunity. In addition, the chronic physical disease that was the second most correlated with depressive and bipolar disorder in this study was liver disease. This is somewhat different from the results reported by the Lancet psychiatric commission. According to almost 100 systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted by the Lancet psychiatric commission [19], there were few papers showing an association between bipolar disorder and hepatitis or liver disease. However, according to papers recently published in Taiwan and China [41,42], there is a high correlation between depressive disorder and chronic liver disease, and it appears that patients with bipolar disorder also have a higher risk of liver disease than the general population. It is possible that such differences may be influenced by race or environment. A multicenter study in several countries may be needed to ascertain the difference.

Although it has been found that the physical problems of people with SMI are significantly different from those of the general population in South Korea, this paper has some limitations. First, while it is possible to establish the type of physical disease patients with SMI have, it is difficult to accurately determine the causal relationship between the two. Our bodies and minds influence each other. We may experience psychiatric difficulties due to physical problems, or we may experience physical difficulties due to psychiatric problems or drugs. Through this study, it was possible to find significant associations between physical disease and mental illness, but it was difficult to determine the cause-and-effect relationship. Considering that the age of onset for SMI (F20–29, F30–31) except F32.3 and F33 is in the 20s and 30s [43,44], it is more likely that the occurrence of mental illness preceded the occurrence of physical illness. However, a prospective cohort study is needed for a clearer causality. Second, there is a possibility of selection bias. This study was based on the data of the NHIC, which is a record of people who visited hospitals for physical and mental diseases. Since the launch of the NHIC in 2000, South Korea has been equipped with a comprehensive health examination system covering all generations and classes through health examinations by life cycle [45,46], but the health screening rate for patients with SMI is lower than that of the general population [47]. Thus, if a patient did not visit the hospital, there is a possibility of omission from this study, and selection bias [48]. Third, a limitation of this study is that it did not consider the potential effects of drugs on the chronic physical disease. According to studies looking at the effects of drugs, psychotropic medications can potentially increase the risk of many physical diseases [49]. Many studies suggest that the prevalence of diabetes mellitus in people with SMI, in particular schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and bipolar disorder, is two to three times higher than that in the general population [50-52]. This is also consistent with the results of this paper. In this study, the probability of diabetes mellitus was 1.02 (Adj. OR) for patients with SMI compared to the general population. However, for F20–29, which is mainly psychosis, it was 1.08, slightly higher than 1.02. In addition, in the results of this study, thyroid disease, which was frequently comorbid with SMI, is also highly likely to be caused by drugs. Hypothyroidism is a common adverse effect of lithium, warranting continued monitoring, and lithium can have adverse effects on the parathyroid gland [53,54]. Finally, liver disease, a chronic physical disease with the highest frequency in patients with SMI, was found to have a higher correlation than the general population in patients diagnosed with F30–31 (bipolar disorder), F32.3, and F33 (major depressive disorder). This is also consistent with the results of other papers [41,55]. This is because liver-specific side effects are frequent during psychiatric drug treatment. Therefore, adjusting for the effects of drugs could yield a more accurate analysis.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine and compare the association of chronic physical diseases between patients with SMI and general population. We found that patients with SMI (F20–29, F30, F31, F32.3 and F33), as defined by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, had more chronic comorbid physical diseases compared to the general population and the difference was analyzed to be significant. This study confirmed the vulnerability of patients with SMI to chronic physical diseases and we were able to identify chronic physical diseases that were highly related to SMI groups among various chronic physical disease. More studies will be needed in the future to investigate the causality of certain chronic physical disease, which more significant in patients with SMI compared to the general population.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are not publicly available, Because the data set for this study was temporarily received through the National Health Insurance Service, we do not have permission to that data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Haewoo Lee. Data curation: Eun Jin Na. Formal analysis: Mi Yang. Funding acquisition: Haewoo Lee, Yoomi Park. Investigation: Eun Jin Na, Haewoo Lee. Methodology: Eun Jin Na, Haewoo Lee. Project administration: Eun Jin Na, Haewoo Lee. Resources: Eun Jin Na, Haewoo Lee. Supervision: Haewoo Lee, Jee Hoon Sohn. Validation: Haewoo Lee. Visualization: Jungsun Lee, Eunjin Na. Writing—original draft: Eunjin Na. Writing—review & editing: Eunjin Na, Haewoo Lee, Hyun-Bo Sim.

Funding Statement

This study was mainly supported by the Seoul Mental Health Welfare Center (Director: Haewoo Lee, MD). The Seoul Mental Health Welfare Center is operated by the Seoul Medical Center, on commission from Seoul City, from Jan 2019.

Acknowledgements

None