Changes in Behaviour Symptoms of Patients with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder during Treatment: Observation from Different Informants

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to determine changes in behaviour among patients with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) by different informants during treatment in the clinical setting.

Methods

Seventy-nine patients with ADHD were recruited. They completed 12-months of treatment with oral short-acting methylphenidate, two-to-three times per day, at a dose of 0.3-1.0 mg/kg. Among the 79 patients (mean age, 9.1±1.9 years), 39 were classified as the ADHD-C/H type (hyperactive-impulsive type and combined type) and 40 as the ADHD-I type (inattentive type). At baseline, and after 12 months, their behaviour was assessed using the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL), Teacher's Report Form (TRF), ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS), and Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S).

Results

Patients classified as the ADHD-C/H type had higher scores on three CBCL subscales, on the ADHD-RS and CGI-S compared to the ADHD-I type patients. After 12-months of treatment, for all patients, there were significant improvements in the four subscales of the TRF as well as the ADHD-RS and CGI-S scores, but not on the CBCL. In addition, the patients with the ADHD-C/H type had greater improvements on the four subscales of the TRF after treatment. However, there were no differences noted on the CBCL, ADHD-RS and CGI-S.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that during treatment, in the clinical setting, there are different assessments of behaviour symptoms, associated with ADHD, reported by different informants. Assessments of behaviour profiles from multiple informants are crucial for establishing a fuller picture of patients with ADHD.

INTRODUCTION

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common childhood and adolescent psychiatric diagnosis, with a reported prevalence of over 5% among school-age children worldwide1 and 7.5% in Taiwan.2 The core symptoms include: inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.3 Aside from these behaviours, there are symptoms characterized by increased rates of emotional dysregulation, disruptive behaviour and social problems.4-6 Such behavioural problems commonly lead to a negative impact on inter-personal relationships, family function and quality of life, among affected individuals.7 Thus, it is important to identify the behaviour profiles of patients with ADHD receiving treatment in the clinical setting.

The behavioural symptoms associated with ADHD may vary across different settings, such as in the home, at school or in a hospital.8 Some researchers have examined the concordance of parent and teacher ratings of symptoms associated with ADHD. For example, it had been reported that parent-teacher agreement for ADHD symptoms is low; this finding may indicated that ADHD symptoms are situation specific.9,10 In addition, Tripp et al.11 suggested that the teacher's report outperforms parental report with regard to the sensitivity and specificity for the accuracy of the ADHD differential diagnosis. Therefore, to obtain a more complete assessment of patients with ADHD, data gathering from multiple informants is essential for both clinicians and researchers.8,12 Nevertheless, there has been no prior study comparing the differences in the assessments of symptoms associated with ADHD observed by the patients' parents, teachers and clinicians.

Numerous rating scales are available for measuring the behavioural symptoms associated with ADHD in different settings. Some narrowband scales target the information from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)-oriented ADHD-symptoms, such as the ADHD Rating Scale (ADHD-RS) or the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale (DBRS).13 By contrast, broadband scales measure a variety of behavioural problems, such as the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL), or the Teacher's Report Form (TRF).14 Generally, compared to narrowband scales, broadband scales are better for establishing a more complete assessment of the changes in behavioural symptoms associated with ADHD among patients. However, research on the use of the CBCL and the TRF to investigate the changes in the behaviour profiles of patients with ADHD, during long-term treatment, remains scarce.15

Based on the current DSM-IV, ADHD is categorized into three subtypes according to the predominant clinical manifestations; these are inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive and combined types. Prior cross-sectional studies that have investigated differences in behaviour profiles among ADHD subtypes have generally indicated that among patients with ADHD, those with the inattentive subtype generally display high rates of problems with attention and social passivity.16,17 By contrast, the hyperactive-impulsive and combined types show more aggressive behaviour and emotional problems.17,18 During treatment in the clinical setting, reports of distinct behavioural changes observed among ADHD subtypes remain controversial.19-22

The aim of the present study was to determine whether the assessment of changes in behavioural symptoms varied among different informants after 12-months of treatment in a clinical setting and to compare the changes in behavioural symptoms among the ADHD subtypes.

METHODS

Study participants

The hospital's Institutional Review Board at Chang Gung Children's Hospital, Taiwan approved the study and the patients' parents provided informed consent. Eligible patients with ADHD at the Out-patient Department of Child Psychiatry, at Chang Gung Children's Hospital, Taiwan were recruited for this study if they: 1) were between 6 and 16 years of age, 2) and were clinically diagnosed with ADHD. Two senior child psychiatrists diagnosed the ADHD and co-morbidities (including learning disorders, tic disorders and oppositional defiant disorder) based on DSM-IV criteria.3 Subjects with ADHD were classified into three types: inattentive, hyperactive-impulsive and combined. 3) The subjects were newly diagnosed with ADHD or had an existing diagnosis but had not taken medication for ADHD in the last six months or more.

Patients were excluded if they 1) had a history of co-morbid pervasive developmental disorders, mental retardation, conduct disorder, bipolar disorder, psychosis, epilepsy, or brain injury. 2) In addition, if patients required additional behavioural therapy or family therapy other than usual practice at Out-Patient Department of Child Psychiatry.

Study procedure

Patients with ADHD were prescribed short-acting oral methylphenidate two-to-three times per day at a dose of 0.3-1.0 mg/kg, based on the severity of their clinical symptoms and their age, height and body weight. Patient care was performed per their usual practice at the Out-Patient Department of Child Psychiatry, but concomitant medications were not permitted. The behaviour profiles of the patients with ADHD were assessed using the CBCL, TRF, ADHD-RS, and Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S). At baseline (pre-treatment), a clinician administered the ADHD-RS and CGI-S to the patients and their caregivers. Each patient's major caregiver and teacher were asked to fill out the CBCL and the TRF, respectively. To investigate the patients' broadband changes in behavioural symptoms, the same assessments were repeated at 12 months from baseline.

Measurements

The CBCL and TRF were completed by children's parents/caregivers and teachers, respectively. They evaluated the social and behavioural competence of the children over the last six months.14 Both the CBCL and TRF consisted of 113 items. A three-point Likert scale was used to assess behavioural/emotional problems at home and at school. Both contained eight narrowband syndromes (i.e., Withdrawn, Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Aggressive Behaviour, and Delinquency) and two broadband syndromes (i.e., Internalizing Problems and Externalizing Problems). A T-score of 50 in each subscale indicated average functioning in reference to the other children of the same age and gender. The Chinese versions of these two tests have been shown to have good reliability and validity.23,24

The ADHD-RS was used, a validated instrument, whereby clinicians assigned ratings based on the information from parent(s) and the child.25 It had an 18-item checklist derived from 18 criteria outlined in the DSM-IV for the diagnosis of ADHD. Each of the items used a 4-point Likert scale of 0 to 3 points. The instrument provided a total score (the sum of all 18 items) that could also be divided into inattentive (odd numbered items) and hyperactive/impulsive subscales (even numbered items). Higher scores indicated a greater severity of ADHD. The scale had good inter-rater reliability.26

The CGI-S, which was rated by clinicians, consisted of only one item that assessed severity; a Likert scale of up to seven was used, ranking 1 as normal (not ill) and seven as extremely ill.27

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the statistical software package SPSS, version 16. Variables are presented as either the mean (±standard deviation) or frequency (%). A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Categorical variables among ADHD subtypes at baseline were compared using the Chi-Square Test or Fisher's Exact Test, as appropriate. The Student's t-test was used to compare the continuous variables. To reduce type I errors, Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) was used as the primary analytic strategy. To examine changes of behaviour profiles after 12 months of treatment, the dependent variables were set as scores on the CBCL, TRF, ADHD-RS, and CGI-S. Controlling for age, gender and co-morbidities, the effects of different behaviour profiles associated with ADHD subtype, time, and the interaction of ADHD subtype by time were investigated.

RESULTS

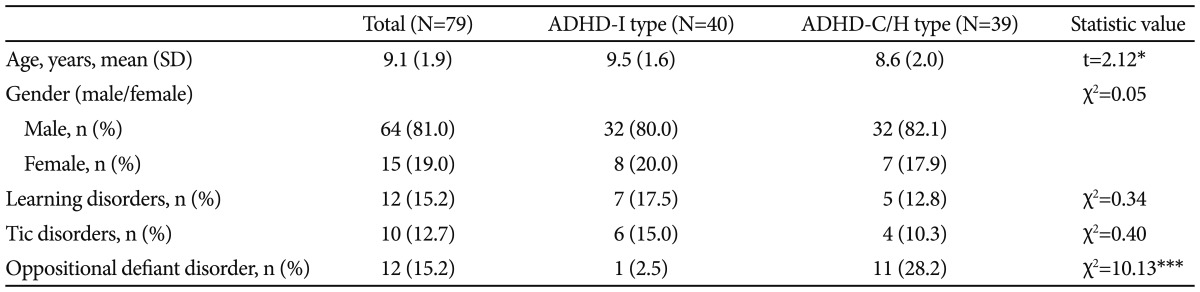

From the 108 ADHD patients initially recruited, 79 (64 boys and 15 girls; mean age, 9.1±1.9 years) remained in the study at 12 months. Among the 79 patients with ADHD, 40 were the inattentive type (ADHD-I type), 5 the hyperactive-impulsive type and 34 combined type. Due to the small number of patients with the hyperactive-impulsive type, they were added to the combined type patients into an ADHD-C/H type for further analyses. The age, gender and co-morbidities of patients with different ADHD subtypes are shown in Table 1.

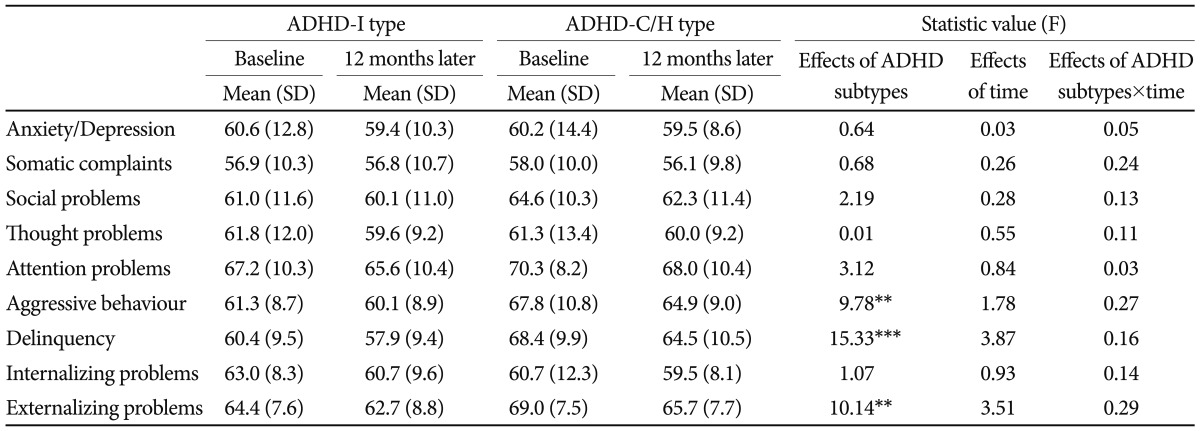

The behaviour profiles on the CBCL of patients with ADHD at baseline and after 12 months are shown in Table 2. Patients with the ADHD-C/H type had higher scores on the CBCL subscales of Aggressive Behaviour (p=0.002), Delinquency (p<0.001), and Externalizing Problems (p=0.002) than patients with the ADHD-I type. There were no significant changes in the scores on all CBCL subscales after 12-months of treatment. There were no effects noted for the interaction of ADHD subtype by time on all CBCL subscales.

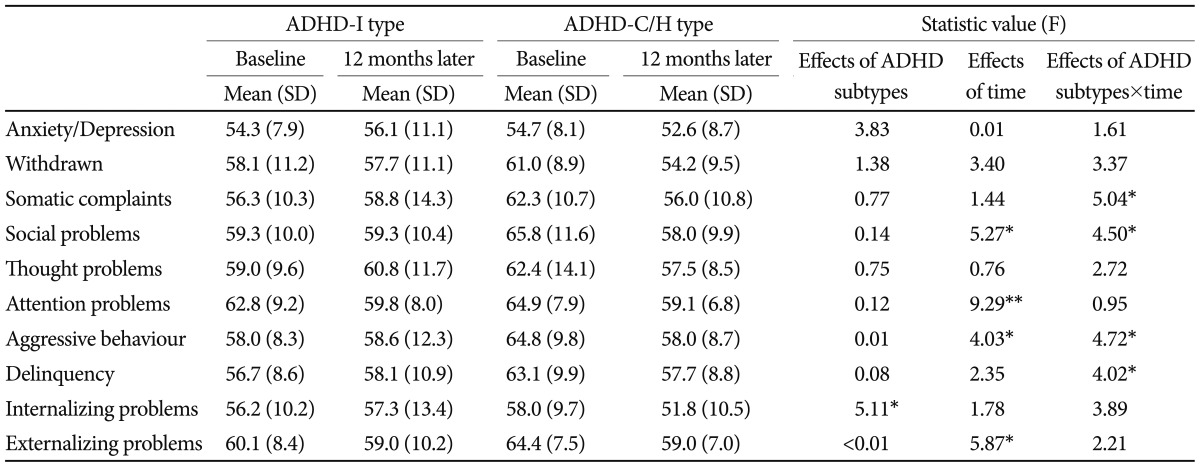

The behaviour profiles on the TRF for the patients with ADHD at baseline and after 12 months are shown in Table 3. Scores on Internalizing Problems were significantly different among the ADHD subtypes (p=0.026). After the 12-months of treatment, there were significant improvements on the TRF subscales of Social Problems (p=0.023), Attention Problems (p=0.003), Aggressive Behaviour (p=0.047), and Externalizing Problems (p=0.017). In addition, there were significant effects on the interaction of ADHD subtype by time on Somatic Complaints (p=0.027), Social Problems (p=0.036), Aggressive Behaviour (p=0.032), and Delinquency (p=0.047).

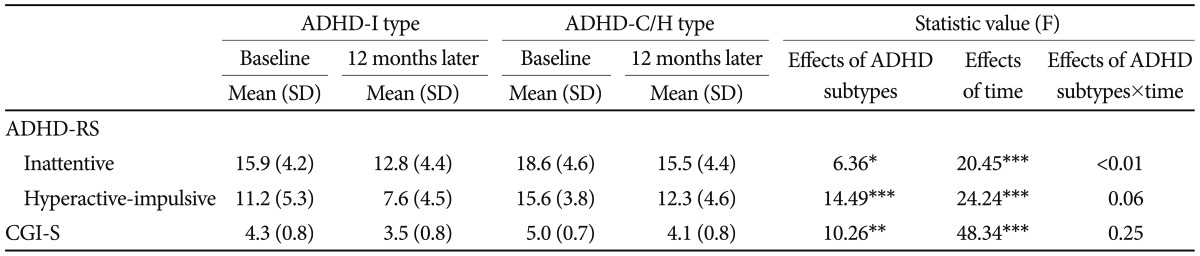

The ADHD-RS and CGI-S scores for the patients wit ADHD at baseline and after 12 months are shown in Table 4. Patients with the ADHD-C/H type had higher scores for inattentive (p=0.013) and hyperactive-impulsive (p<0.001) subscales on the ADHD-RS and in CGI-S (p=0.002) than patients with the ADHD-I type. After the 12-months of treatment, scores on the inattentive (p<0.001) and hyperactive-impulsive (p<0.001) subscales of the ADHD-RS and CGI-S (p<0.001) were all significantly decreased. There were no effects noted on the interaction of ADHD subtype by time.

DISCUSSION

From the perspective of patient caregivers, the behavioural symptoms of patients with ADHD at home, as measured by the CBCL, did not improve after 12 months of treatment. Among the ADHD subtypes, there were disparities in some of the CBCL dimensions that represent disruptive and externalization of behaviour. However, the interaction of the ADHD subtype by time of treatment had no effects. Previous international studies indicated that patients with the ADHD-combined type have greater severity on many of the CBCL subscales compared to patients with the ADHD-inattentive type.28,29 The findings of the current study are generally consistent with prior reports. However, previous research that used DSM-oriented ADHD-symptom rating scales for outcome measurements have demonstrated significant improvements in the parent-rated behavioural symptoms.21,30 Changes in the DSM-oriented ADHD-symptoms were reported not to be significantly different among ADHD subtypes after treatment.31 The CBCL, which is a major assessment tool used in the current study, covers a broad range of behavioural syndromes, it not only targets the DSM-oriented ADHD core symptoms. The discrepancy in measurement tools may explain some of the inconsistent findings among studies. Furthermore, most of the patients in this study were lower grade students in elementary school, with home time after school in the afternoon. This may explain the difference in report of changes in behaviour between parents and teachers.

The teachers reported that the severity of Social Problems, Attention Problems, Aggressive Behaviour, and Externalizing Problems significantly decreased after 12 months of treatment. Previous studies that focused on the efficacy of behaviour training programs have not reported findings consistent with the results of this study.15,32 That is, teachers perceive fewer benefits with regard to the children's behavioural symptoms than did parents. It is the parents, not the teachers that take the children with ADHD to behavioural training programs. Therefore, the differences noted in the assessment of children's behavioural improvements might have been influenced by placebo effects or information bias. After a treatment mostly with medication in the current study, teachers, but not parents, perceived improvements in the children's behaviour symptoms at school. In addition, patients with the ADHD-C/H type seemed to have more improvements from treatment, as noted on many of the dimensions of the TRF, compared to patients with the ADHD-I type. Such differences were not found in the parent-rated and clinician-rated symptoms. From the point of view of teachers, Gorman et al.19 found that children with the ADHD-combined type had a greater decrease in hyperactivity and aggression behaviours than children with the ADHD-inattentive type during treatment. However, other studies that have investigated similar topics have reported conflicting findings.21,31 Whether teachers are more sensitive to detecting differences in behaviour changes among ADHD subtypes warrants further research.

With regard to clinician-rated scores, patients with the ADHD-C/H type showed more severe findings on the ADHD-RS and CGI-S compared to the patients with the ADHD-I type. After 12 months of treatment, the scores on the ADHD-RS and CGI-S significantly decreased, and the magnitude of improvement seemed to be greater than the rating given by caregivers and teachers. The ADHD-RS is an 18-item DSM-oriented ADHD-symptom rating scale that does not measure behavioural symptoms other than those given by the DSM-IV diagnosis criteria.25 Determination of the treatment effects on ADHD might be more sensitive if based on the core symptoms of ADHD. However, those who rated the scales were also the clinicians responsible for the treatment plan. These clinicians would be alert to patient improvement after treatment. Such a rating bias, therefore, may lead to false assessment of obvious improvement with regard to the symptoms associated with ADHD. In addition, clinician-rated scores commonly rely on caregivers' report or on direct observation in the clinical setting.8 Patients with the ADHD-C/H type often are more fidgety and disruptive than those of the ADHD-I type. Such observations may explain the significant differences in ADHD-RS and CGI-S among ADHD subtypes.

This study had several limitations. First, the informants used different scales and questionnaires. There are certain inherent differences in the targets of measurement, sensitivity, and validity among these scales. Moreover, this study did not include any neuropsychological instruments, such as a continuous performance test, to assess the attention function of the patients. Due to lack of a referenced criterion, the results of this study could not reveal whether patients really improved in their attention domain after treatment. Second, although the MANCOVA was used to reduce type I errors, some statistical differences may just be caused by chance fluctuation. The effects of time-related decline in behavioural symptoms may be attributed to the natural course of ADHD or to treatment the clinical setting. However, there was no control group to further define this issue in the current study. Due to concerns with regard to the ethical treatment of patients with ADHD, it is difficult to assign a comparison group without treatment. Third, depression or anxiety disorders, which are common comorbid emotional problems in children with ADHD, were not systematically screened for in this study. Furthermore, all of the patients were enrolled from a single site. In the beginning of the study, the number and reasons for excluded patients were not recorded. The distributions in gender and ADHD subtypes in the study population were not compatible with previous epidemiological studies.1,2 A selection bias, therefore, probably existed in this study and influenced the results. Forth, the treatment procedure was not standardized in this study. Although all of the patients with ADHD received medication for treatment (short-acting methylphenidate), drug adherence and the frequency of visits to the outpatient department were not systematically measured. Moreover, the engagement and attitude of caregivers towards treatment may have influenced perception regarding the children's behavioural symptoms. Lastly, most of the patients attended elementary school and their teachers may have been influenced by their ascending grade. Variations in inter-rater reliability may also have confounded the results.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that different observers reported different changes in behavioural symptoms among patients with ADHD after 12-months of treatment in the clinical setting. Obtaining assessments of behaviour profiles from multiple informants is crucial for establishing a more complete understanding of patients with ADHD. Whether differences in behaviour reported can be explained by the assessment tools used, the perception of those doing the assessment or patient behavioural performance warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (CMRPG260181).