The Relationship of Sexual Abuse with Self-Esteem, Depression, and Problematic Internet Use in Korean Adolescents

Article information

Abstract

The association of sexual victimization with self-esteem, depression, and problematic internet use was examined in Korean adolescents. A total of 695 middle and high school students were recruited (413 boys, 282 girls, mean age, 14.06±1.37 years). The participants were administered the Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form (ETISR-SF), Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), and Young's Internet Addiction Test (IAT). The associations between sexual abuse and the level of self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and problematic internet use were analyzed. Adolescents who had experienced sexual abuse showed lower self-esteem, more depressive symptoms, and greater problematic internet use compared with adolescents who had not experienced sexual abuse. In the path model, sexual abuse predicted lower self-esteem (β=-0.11; 95% CI=-0.20, -0.04; p=0.009), which predicted higher depressive symptoms (β=-0.34; 95% CI=-0.40, -0.27; p=0.008). Depressive symptoms predicted problematic internet use in a positive way (β=0.23; 95% CI=0.16–0.29; p=0.013). Sexual abuse also predicted problematic internet use directly (β=0.20; 95% CI=0.12–0.27; p=0.012). The results of the present study indicate that sexually abused adolescents had a higher risk of depression and problematic internet use. For sexually abused adolescents, programs aimed at raising self-esteem and preventing internet addiction, as well as mental health screening, are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Child victimization including childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is an important etiological factor in the development of several psychiatric disorders or symptoms in both childhood and adulthood.1 Among adolescents, commonly reported sequelae include sexual dissatisfaction, promiscuity, and an increased risk of revictimization. Depression and suicidal behavior or ideation are more common in sexually abused adolescents compared to normal and psychiatric nonabused controls.2

A mechanism that may help to explain the distress of sexually abused children is the potential damage to self-concept, leading to a proliferation of negative self-evaluations and negative core beliefs, including a sense of inferiority and low self-efficacy.34 Many studies have demonstrated an association between sexual abuse and low self-esteem in children.56 Given that declines in self-esteem may be direct outcomes of sexual victimization, self-esteem may represent mediators between sexual victimization exposure and mental health outcomes.

Problematic internet use is characterized by an individual's inability to control his/her use of the internet resulting in marked distress and/or functional impairment.7 In previous studies, problematic internet use was encountered in approximately 10–30% of Korean junior or senior high school students,78910 and highly associated with adolescent depression.789111213 Several studies mentioned that lower self-esteem triggers excessive internet use1415 and a significant correlation emerged between depression, self-esteem, and internet addiction.1617

Although both the association between sexual victimization and self-esteem and depression and the association between self-esteem, depression, and problematic internet use have been confirmed by previous studies, the direct association between sexual victimization and problematic internet use has not been examined. In this respect, this study examined the association of sexual victimization with self-esteem, depression, and problematic internet use in Korean adolescents. Based on the previous reports of the adverse effects of sexual victimization on self-esteem and depression,18 which are associated with problematic internet use,1617 it was hypothesized that 1) sexual victimization is related to problematic internet use and 2) this tentative association is partially mediated by a decline in self-esteem and increased depressive symptoms.

METHODS

Participants

A total of 802 students (413 boys, 282 girls) between the 7th and 11th grade (mean age, 14.06±1.37 years) were recruited from one junior high school and one senior high school that were located in Seoul, Korea. These schools volunteered to participate in this study. After the school principals approved the research, the investigators visited the schools, explained the purpose of the study to the students and teachers, obtained consent from the students, and distributed and collected the questionnaires. The authors also mailed letters to parents that outlined the study's objectives, guaranteed confidentiality, provided a contact telephone number for the principal investigator and indicated that parents would be informed of the results after the analyses were completed. The letter also included a statement that parents were free to refuse to respond if they did not agree with the study's objective. This study was approved by the human subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB) (No. C-1412-081-633) at Seoul National University Hospital.

Measures

The Early Trauma Inventory Self Report-Short Form

The ETISR-SF is a 27-item questionnaire used for the assessment of physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and general traumatic experience that may have occurred before age 18. The measure has been shown to have excellent validity and internal consistency.1920 Sexual abuse was defined as unwanted sexual comments or contact performed solely for the gratification of the perpetrator or for the purposes of dominating or degrading the victim, and was assessed by six corresponding items. Each traumatic experience was scored dichotomously (yes=1/no=0). Subjects who experienced any sexual abuse were placed in the sexually abused group, and subjects who did not experience such an event were placed in the non-abused group.

Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale

RSES is a widely used self-report instrument that measures global self-worth. It has ten items. Participants answer each item on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total score ranges from 10 to 50.2122

The Children's Depression Inventory

The CDI is a 27-item, self-rated, symptom-oriented scale that is suitable for youth aged 7 to 17. Each CDI item consists of three statements that are rated on a scale that ranges from 0–2. The total score ranges from 0 to 54.2324

Young's Internet Addiction Test

IAT, developed for screening and measuring levels of internet addiction, is a 20-item questionnaire that uses a five-point Likert Scale. In the IAT, internet-related behavioral problems and psychological distress problems are covered. An IAT score of 50 to 79 is regarded as a mild degree of internet addiction (i.e., occasional problems with internet use). A score of 80 or greater is regarded as a severe degree of internet addiction (i.e., having significant problems in daily life).2526 A higher score indicates a greater level of addiction. The total score ranges from 20 to 100.

Statistical analyses

We compared the characteristics of the sexually abused group and the non-abused group using independent t-tests for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables. SPSS (version 21.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. We also used AMOS (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to conduct path analyses. Sexual abuse state, the RSES scores, CDI scores, and IAT scores were included in the path model. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

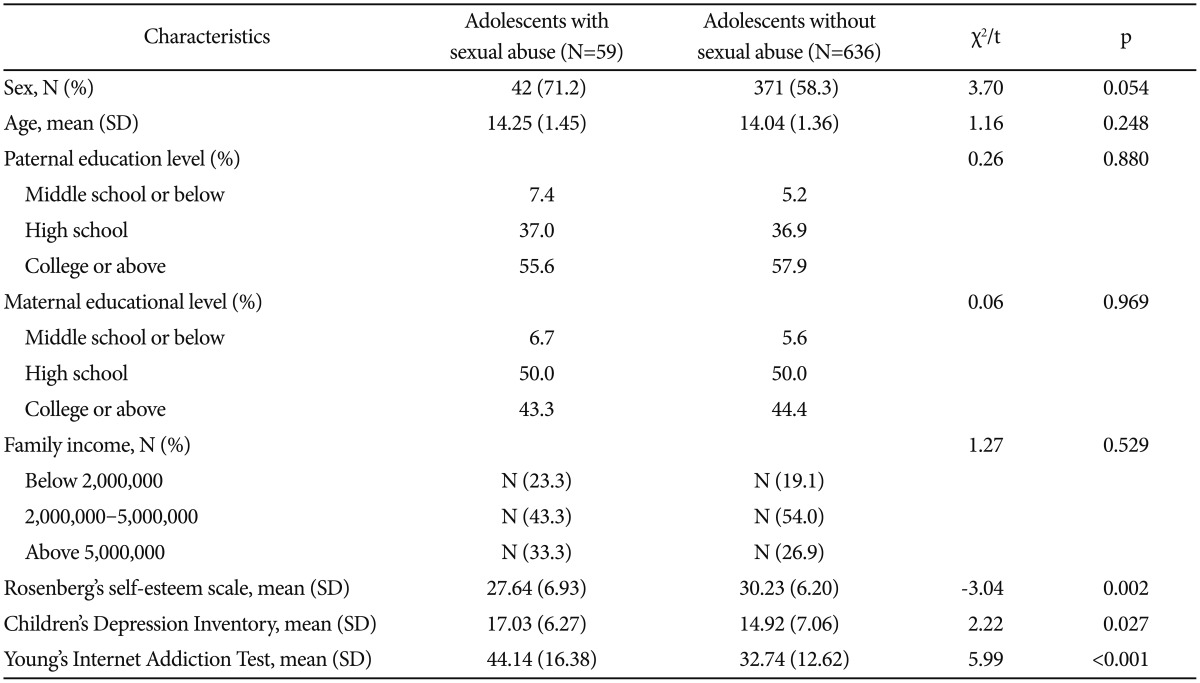

Of the 802 students initially recruited in the study, 107 were excluded due to incomplete responses, which resulted in 695 subjects (413 boys, 282 girls, mean age, 14.06±1.37 years). Table 1 shows the group-specific demographic and clinical characteristics. There were no significant differences in age, sex, parental educational levels, and family income between the groups. The sexually abused group showed lower RSES (t=-3.04, p=0.002), higher CDI (t=2.22, p=0.027), and higher IAT (t=5.99, p<0.001) scores compared with those in the non-abused group.

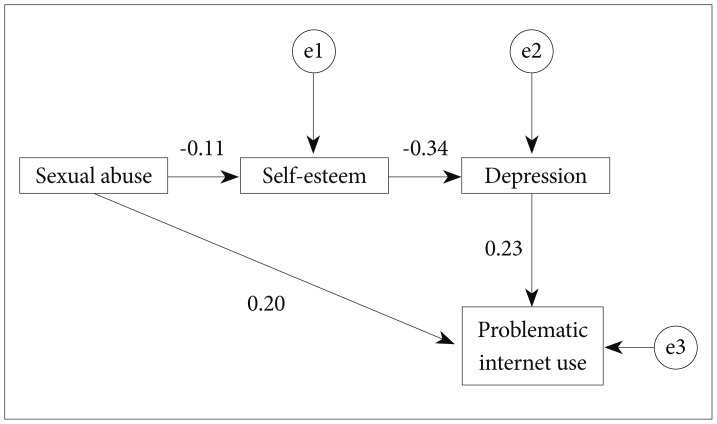

In the path model, sexual abuse predicted lower self-esteem (β=-0.11; 95% CI=-0.20, -0.04; p=0.009), which predicted higher depressive symptoms (β=-0.34; 95% CI=-0.40, -0.27; p=0.008). Depressive symptoms predicted problematic internet use in a positive way (β=0.23; 95% CI=0.16–0.29, p=0.013). Sexual abuse also predicted problematic internet use directly (β=0.20; 95% CI=0.12-0.27; p=0.012). The path model showed an excellent fit to the data (GFI=0.999, AGFI=0.994, CFI>0.99, RMSEA<0.001, chi-square=1.80 and chi-square p-value=0.406) (Figure 1).

Path analysis showing associations between sexual abuse, self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and problematic internet use in adolescents. Sexual abuse predicts problematic internet use both directly and indirectly via mediation by lower self-esteem and higher depressive symptoms. Only significant paths are presented.

DISCUSSION

The primary goal of this study was to investigate the relationship of sexual victimization with self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and problematic internet use in Korean adolescents. Our findings indicate a significant association between sexual victimization and problematic internet use, which is partially mediated by low self-esteem and increased depressive symptoms.

The observed association between sexual victimization, lower self-esteem, and depression is consistent with previous studies.256 Turner et al.18 reported that sexual victimization independently reduced self-esteem and that declines in self-esteem partially mediated the association between past-year sexual victimization exposure and levels of depressive symptoms. In our path model, lower self-esteem fully mediated the association between sexual victimization and depressive symptoms.

In addition to such a well-known relationship, we found that sexual victimization was associated with problematic internet use in adolescents. The mean IAT score for the sexually abused group indicates a mild degree of internet addiction (i.e., occasional problems with internet use), while the score for the non-abused group indicates average internet users (i.e., having no problems with internet use). Consistent with our hypothesis, this association was partially mediated by low self-esteem and high depressive symptoms. However, even after excluding the mediating effect of self-esteem and depressive symptoms, there was a significant association between sexual victimization and problematic internet use. Childhood sexual abuse may lead to maladaptive coping skills, disturbed self-identity, poor interpersonal skills, and lack of intimacy, as well as low self-esteem.2728 According to the social learning theory postulated by Bandura,29 low self-efficacy and poor coping strategies elicit the risk of developing addictions to cope. Cognitive-behaviorists also suggest that disruption in the areas of identity formation and developing meaningful relationships or intimacy may lead the individual to use the internet as a means of escape and emotional numbing or fulfilling developmental intimacy needs.30 Therefore, such a variety of correlates or mediators should be examined to identify the true relationship between sexual victimization and problematic internet use in future studies.

Our study had several limitations. First, due to the subjects being asked to recall trauma that they experienced in the past, the respondents' reports may be characterized by inaccuracies. Second, this study was cross-sectional; thus, we could not identify causal relationships between sexual victimization, self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and problematic internet use. Finally, the schools volunteered to participate in the study. Therefore, our findings may not be representative of all Korean adolescents and future studies should include larger, more representative samples.

The results of the present study indicate that adolescents who experienced sexual abuse are at greater risk of depression and problematic internet use. A clinical implication of this study is that treatment for adolescents who experienced sexual abuse should include mental health screening, interventions to raise self-esteem, and internet addiction prevention programs. Future prospective studies are needed to further clarify the causal relationships among childhood sexual abuse, depression, and problematic internet use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) Grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIP) (NRF-2014R1A1A3049818).