Screening Ability of Subjective Memory Complaints, Informant-Reports for Cognitive Decline, and Their Combination in Memory Clinic Setting

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to compare the accuracy of subjective memory complaints, informant-reports for cognitive declines, and their combination for screening cognitive disorders in memory clinic setting.

Methods

One-hundred thirtytwo cognitively normal (CN), 136 mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and 546 dementia who visited the memory clinic in the Seoul National University Hospital underwent standardized clinical evaluation and comprehensive neuropsychological assessment. The Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire (SMCQ) and the Seoul Informant Report Questionnaire for Dementia (SIRQD) were used to assess subjective memory complaints and informant-reports for cognitive declines, respectively.

Results

Both SMCQ and SIRQD showed significant screening ability for MCI, dementia, and overall cognitive disorder (CDall: MCI plus dementia) (screening accuracy: 60.1–94.6%). The combination of SMCQ and SIRQD (SMCQ+SIRQD) was found to have significantly better screening accuracy compared to SMCQ alone for any cognitive disorders. SMCQ+SIRQD also significantly improved screening accuracy of SIRQD alone for MCI and CDall, but not for dementia.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the combined information of both subjective memory complaints and informant-reports for cognitive declines can improve MCI screening by each individual information, while such combination appears not better than informant-reports in regard of dementia screening.

INTRODUCTION

Subjective memory complaints and informant-reports of memory decline are considered as important predicting factors of cognitive disorders including mild cognitive impairment and dementia,1234 and especially useful in predicting Alzheimer's dementia which accounts for 70% of overall dementia.34

There have been many studies reporting that subjective memory complaints predict conversion to dementia in older population.34567891011 Also, a study of community-dwelling elderly aged 65 years and older reported that the group with subjective memory complaints showed greater cognitive impairment in neuropsychological assessment compared to the group without subjective memory complaints,12 suggesting subjective memory complaints might be capable of screening cognitive disorders.

Recent studies support the diagnostic prediction ability of subjective memory complaints with biological evidences.131415 Laws et al.14 reported that elderly people with subject memory complaints showed significantly greater atrophy of hippocampus compared to the ones without subjective memory complaints. Jorm et al.15 reported that elderly population with e4 allele of APOE gene showed significantly more subjective memory complaints.

However, subjective memory complaints have been considered to be less reliable than informant-reports of memory decline in discriminating cognitive disorders, because it can be influenced by factors such as personality trait, mood and anxiety at the time of the complaints.1314 A number of studies reported that it did not predict cognitive disorders.16

Meanwhile, numerous studies have been constantly reporting that informant-reports of memory decline discriminates cognitive disorders with clear validity. Recent studies reported that informant-reports of memory decline predicted cognitive disorders, even before clinical diagnosis by standard assessments,17 and also it detected cognitive disorders even in earlier stage of disease process than MCI.18 A recent study subjected to community-dwelling elderly population reported that for the group with objective cognitive impairment, informant-reports of memory decline screened cognitive disorders more accurately compared to subjective memory complaints.19 On the basis of results reported by numerous studies, a variety of informant questionnaires with reliability and validity in screening MCI and dementia have been developed and utilized in clinical practices and researches.15202122

As described above, subjective memory complaints and informant-reports of memory decline both seem to be capable of screening cognitive disorders. However, few studies compared the screening ability of subjective memory complaints, informant-reports of memory decline, and the combination of the two.

This study aimed to compare the screening accuracy of subjective memory complaints, informant-reports of memory decline and the combination of these two for discriminating cognitive disorders including MCI and dementia in memory clinic setting.

METHODS

Participants

Total 814 subjects who visited dementia clinic of Seoul National University Hospital participated in this study. All of them were aged 50 and older and included 132 cognitively normal (CN), 136 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) (120 amnestic MCI and 16 non-amnestic MCI), and 546 dementia [379 Alzheimer dementia (AD) and 167 non-Alzheimer dementia (NAD)].

Dementia was diagnosed according to the criteria of the the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV),23 and AD was diagnosed according to the probable or possible AD criteria of National Institute of Neurological and Communication Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS-ADRDA).24 A diagnosis of MCI was made according to Peterson criteria.25

The exclusion criteria for participants included 1) individuals with major medical, psychiatric or neurological conditions that could affect cognitive functions, 2) individuals with communication or behavioral problems that could make a clinical assessment difficult, 3) individuals without reliable informant, and 4) individuals with limited ability of reading Korean that could make a neuropsychological assessment difficult. Individuals with minor physical conditions such as mild hearing loss, essential hypertension, diabetes with no serious complication etc. were included in this study.

Clinical and neuropsychological assessment

All participants in this study were examined by psychiatrists with advanced training in dementia research according to Korean version of Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Packet (CERAD-K) clinical assessment battery.26

Cognitive functions of participants were assessed by trained clinical psychologists according to CERAD-K neuropsychological battery. CERAD-K neuropsychological battery consists of 15-item Boston Naming Test, Word List Memory, Word List Recall, Word List Recognition, Constructional Praxis, Constructional Recall, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

A panel of four or more psychiatrists with expertise in dementia research confirmed diagnosis through comprehensive examination and discussion of all the available raw data.

All the participants' subjective memory complaints were measured by the Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire (SMCQ),12 and informant-reports for memory decline were assessed by the Seoul Informant Report Questionnaire for Dementia (SIRQD).27 Scores of SIRQD-supplemented SMCQ (SMCQ+SIRQD) were derived from simply summing the scores of SMCQ and SIRQD.

SIRQD is an informant questionnaire which consists of 15 items, and the highest possible total score is 30 points. SIRQD takes a short time to complete and provide vital information about patient's cognitive impairment efficiently. It is also proved to have reasonable reliability and validity, and especially shows low chance of false positive and false negative when applied to elderly people with wide range of educational level such as Korean elderly population.27

SMCQ is a self-reporting questionnaire for elderly people to report their memory problems in general and in daily living, which consists of 14 items and the highest possible total score is 14 points. SMCQ is reported to have reasonable reliability and validity, and showed significant associations with objective cognitive impairment assessed by neuropsychological batteries.12

Statistical analysis

Between-group comparisons of demographic and clinical data of 814 participants were performed by two-tailed t-test and χ2 test. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the ability of SMCQ, SIRQD and SMCQ+SIRQD for screening three different cognitive disorder groups, i.e., MCI, dementia and overall cognitive disorder (CDall: MCI plus dementia) groups, and the differences of -2 log likelihood (-2LL) was used to compare the predictive ability of the SMCQ, SIRQD, and SMCQ+SIRQD scores. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were also conducted to compare the screening accuracy by the three scores for each diagnostic groups, and the areas under curve of ROC were compared using the method of Hanley and McNeil.28

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics

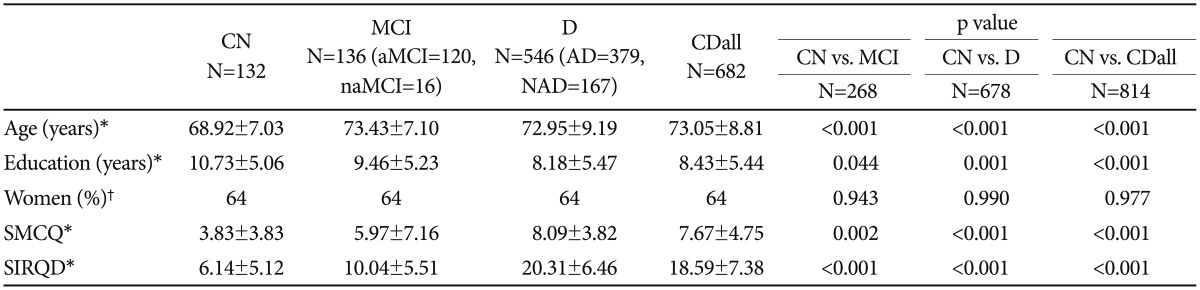

Among 814 participants, 64% were female. CN showed significant differences in age, education, SMCQ and SIRQD scores compared to MCI, dementia and CDall (p<0.05) (Table 1).

Logistic regression analysis and the differences of -2 log likelihood

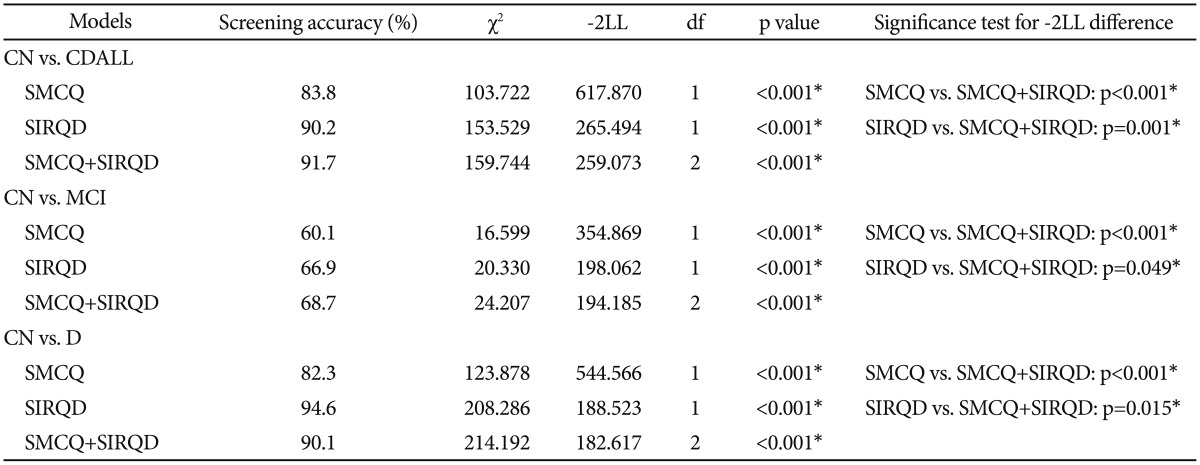

All three logistic regression models including SMCQ, SIRQD and SMCQ+SIRQD significantly discriminated MCI, D and CDall from CN (screening accuracy: 60.1–94.6%) (p<0.001). When compared to each other, SMCQ+SIRQD model showed significantly higher screening accuracy compared to SMCQ model in predicting any cognitive disorders (p<0.001). However, compared to SIRQD model, SMCQ+SIRQD model showed significantly better only for screening MCI (p=0.049) and CDall (p<0.001), but for dementia (p=0.015). In regard of dementia screening, SIRQD alone model had the highest accuracy among the three models (Table 2).

ROC curve analysis

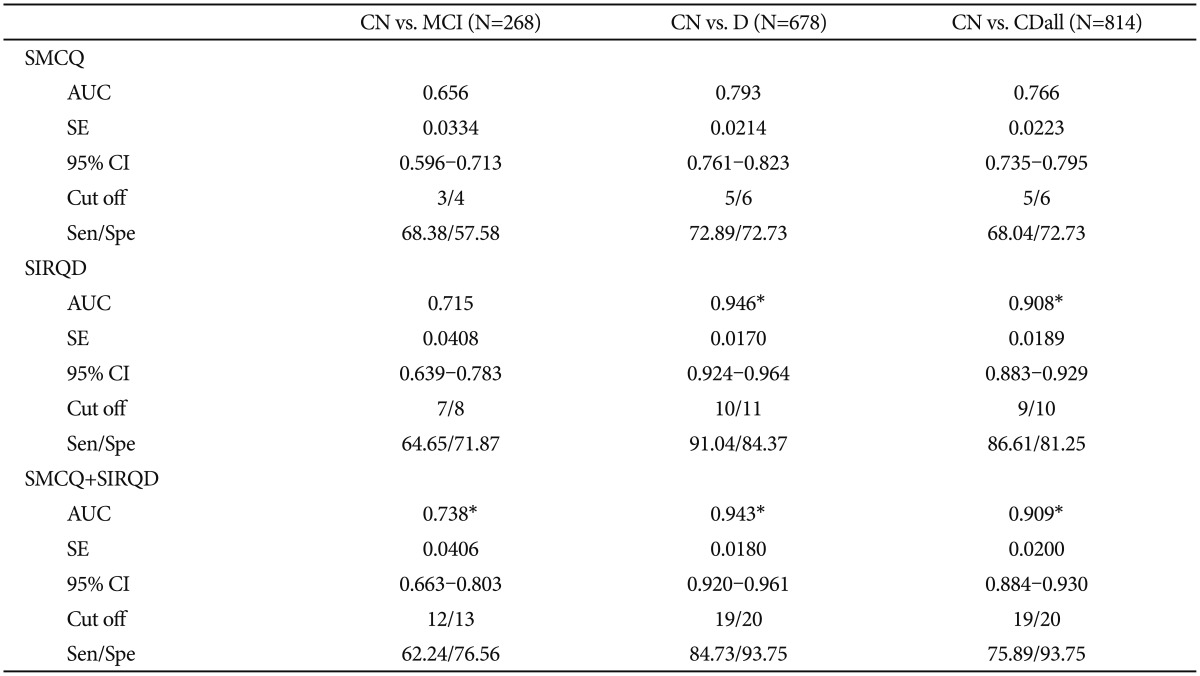

The results of ROC curve analysis showed that SIRQD had significantly greater AUC than SMCQ in screening D and CDall (p<0.05) (Table 3, Figure 1). SMCQ+SIRQD showed significantly greater AUC than SMCQ in screening MCI, D and CDall (p<0.05), but the AUC of SMCQ+SIRQD had no difference with that of SIRQD for screening any of the three diagnostic groups.

Area under curves (AUC) and cut-off scores of SMCQ, SIRQD, and SMCQ+SIRQD in CN, dementia and overall cognitive impairment

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of Subjective Memory Complaints Questionnaire (SMCQ), Seoul Informant Report Questionnaire for Dementia (SIRQD), and SIRQD supplemented SMCQ (SMCQ_SIRQD) in screening for (A) cognitively normal (CN) versus mild cognitive impairment (MCI), (B) CN versus dementia and (C) CN versus overall cognitive disorder (MCI+dementia).

DISCUSSION

Logistic regression analyses showed that all three models including SMCQ, SIRQD and SMCQ+SIRQD, respectively, significantly discriminated MCI, D and CDall from CN. It is consistent with previous researches in supporting that both subjective memory complaints and informant-report of memory decline not only predict conversion to cognitive disorders of various levels.31129 but also screen cognitive disorders of various levels.303132

There have been a few researches exploring combination models of various screening tools to improve screening ability of cognitive disorders. One study explored verbal fluency-supplemented-MMSE model which has better assessment of frontal lobe function, to improve screening ability.33 Another study explored the usefulness of neurodegenerative quantification using models of various biological markers such as cortical thickness, glucose metabolism, hippocampal volume of brain.34 There were also a study exploring diagnostic predicting ability of models of different combinations of MMSE, brain MRI and PET,35 and a study verifying screening ability of combination models of certain neuroimaging markers.36 Results of these studies proposed that combination of various screening tools and biological markers improved the screening ability for cognitive disorders, which are consistent with the result of this study.343536 While our study has a consistent result with previous studies, it differs from other studies in that the screening tools included both subjective and objective tools which are SMCQ, self-reporting questionnaire for memory complaints and SIRQD, informant-report of participants' memory decline.

In comparisons of screening ability among the three different models by the differences of -2LL, SMCQ+SIRQD model showed significantly higher screening accuracy compared to SMCQ model in any cognitive disorders, which is consistent with previous studies that reported combination of certain screening tools improved the screening ability of cognitive disorders.3337 On the other hand, SMCQ+SIRQD model showed significantly higher accuracy only in screening MCI and CDall compared to SIRQD model, while it showed significantly lower screening accuracy for dementia. As for dementia, SIRQD model showed the highest screening accuracy of 94.6%. These results are consistent with previous studies which reported that subjective memory complaints did not show consistent screening ability in all levels of cognitive disorders.3839 The results of ROC curve analysis also showed that while SMCQ+SIRQD had significantly higher accuracy than SMCQ in screening MCI, D and CDall, the combination had no differences compared to SIRQD. These results indicate that the screening accuracy of the combination model was not always superior to the individual tools, as shown in the results of the regression analyses.

Subjective memory complaints have been reported to predict conversion of the cognitively normal without objective cognitive impairment in neuropsychological assessments to MCI or dementia in several longitudinal studies,3040 but there was also a cross-sectional study reporting that it had a limited screening ability for cognitive disorders.41 There are also studies reporting that subjective memory complaints in cognitively normal and MCI groups of elderly, showed statistically significant association with cognitive impairment assessed by neuropsychological batteries, and the higher the cognitive impairment, the higher the level of subjective memory impairment were.12324243 However, a number of studies reported that in a group who has progressed to dementia, subjective memory complaints did not have any association with objective cognitive impairment, but the tendency of anosognosia, which is deficit of self-awareness of diseases, increases.444546 Anosognosia in healthy volunteers has been reported to be involved with prefrontal cortex, temporoparietal junction and posterior dorsomedial regions of parietal lobe including the precuneus,4748 and decline of regional cerebral blood flow in those regions has been reported in early stage of AD dementia.4950 Anosognosia in dementia group could be considered to be a major cause of the result that SMCQ+SIRQD model did not show significantly higher screening ability for dementia compared to SIRQD.

Therefore, it may not be the best to simply summing the scores of tools assessing subjective memory complaints and informant-reports of cognitive decline in all cognitive disorders to obtain the score for the combination model of the tools, because it does not consider severity of cognitive impairment which could cause discrepancy between the results of assessments. Rather, a detailed screening model which considers the discrepancy between subjective memory complaints and informant-reports of memory decline depending on the level of actual cognitive impairment could be needed.

Limitations of this study are as follows: 1) this study did not control personality traits and mood states which could affect participants' subjective memory complaints and informant-reports of memory decline. Mood states such as depression and anxiety and personality traits could exaggerate subject memory complaints and also allow informants to misinterpret cognitive disorders as personality or mood problems themselves. If these variables were controlled, the reliability of the results could be increased. 2) this study did not subdivide groups of MCI and dementia by severity and types of cognitive decline. If detailed subdivision within each group of cognitive disorder was executed, it could have been possible to explore the predicting ability of screening models depending on the severity or type of cognitive decline. 3) as this is a cross-sectional study, it was able to explore the cross-sectional screening ability of different models, but was not able to explore the ability of the models in predicting conversion to further level of cognitive disorders.

Strengths of this study are not only a large sample size, but also a panel of psychiatrists with expertise in dementia research confirmed diagnosis through comprehensive examination and discussion of all the available raw data, therefore in comparisons of groups results of higher reliability could be derived. Also, this study is unique and new in that it explored a combination model of subjective and objective tools, compared to previous studies which explored only the objective tools such as biological markers, neuropsycological assessment and questionnaires or exams completed by observers.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that each of subjective memory complaints reported by patients themselves, reports of cognitive decline by informants, and the combination of both are all useful for screening of MCI and dementia. The combined information of both subjective memory complaints and informant-reports of memory decline can also improve MCI screening ability of each individual information. However, such combination appears not better than informant-reports alone in regard of dementia screening.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning, Republic of Korea (Grant No. NRF-2014M3C7A1046042).