The Effect of Cognitive Behavior Therapy-Based Psychotherapy Applied in a Forest Environment on Physiological Changes and Remission of Major Depressive Disorder

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Psychotherapeutic intervention combined with pharmacotherapy is helpful for achieving remission of depressive disorder. We developed and tested the effect of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT)-based psychotherapy applied in a forest environment on major depressive disorder.

Methods

We performed 4 sessions during 4 weeks (3 hours/session) in patients with major depressive disorder during pharmacotherapy. For the forest group, sessions were performed in the forest; for the hospital group, sessions were performed in the hospital. The control group was treated with the usual outpatient management.

Results

A total of 63 patients completed the study: 23 in the forest group, 19 in the hospital group, and 21 in the control group. Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression (HRSD) scores of the forest group were significantly decreased after 4 sessions compared with controls. Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scales (MADRS) scores of the forest group were significantly decreased compared with both the hospital group and the controls. The remission rate (7 and below in HRSD) of the forest group was 61% (14/23), significantly higher than both the hospital group (21%, 4/19) and the controls (5%, 1/21). In heart rate variability (HRV) analysis, some measurements representing HRV and parasympathetic nerve tone were increased in the forest group after 4 sessions. The salivary cortisol levels of the forest group were significantly decreased.

Conclusion

CBT-based psychotherapy applied in the forest environment was helpful in the achievement of depression remission, and its effect was superior to that of psychotherapy performed in the hospital and the usual outpatient management. A good environment such as a forest helps improve the effect of psychotherapeutic intervention because it includes various natural instruments and facilitators in the treatment of depression.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder is a long-lasting illness with significant effects on family, social, and work life.1,2 Because of its high prevalence, its resultant socioeconomic burden is growing, and has become even higher than angina, arthritis, asthma, or diabetes.3 Treatment failure results in frequent relapses and a low recovery rate.4 Up until 10-20 years ago, the treatment goal of depression was merely relief of acute symptoms by pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy.5,6 Recently it was shown that patients continuously suffer from residual depressive symptoms and have high relapse rate and poor prognosis when in partial remission.8 With the advent of fluoxetine, antidepressants started showing fewer side effects and improved patient medication compliance.9 Therefore, a consensus arose to adjust therapeutic goals to complete remission rather than merely symptomatic improvements.10 Correspondingly, after year 2000, practice guidelines of major countries including the United States and England encouraged changing the therapeutic goal of major depressive disorder to induce complete remission,11 and recently the therapeutic guideline from the Korean Society of Depressive and Bipolar Disorder recommended 'recovery of all pre-morbid functions through a complete remission' as a new therapeutic goal.12

Much effort is required to achieve complete remission. A combination of substantial amounts of maintenance therapy, antidepressant medications, and education is used to increase patient adaptation. The antidepressant-only remission rate is usually not higher than 40% in well-designed double blind studies.13 It was thought that combination pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy would help increase remission rates14 because it is difficult for patients to immediately recover vitality simply by normalizing neurotransmitter metabolisms inside the brain after a long-lasting lethargic condition and habitual low activity levels. The physical symptoms of anxiety disorder are readily responsive to medications, but behavioral symptoms such as avoidance responds better to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT).15 Use of CBT in depressive patients has proven effective and is being widely applied, and behavioral techniques that are used to increase patient activity can also be used for rehabilitation and relapse prevention.16 Therefore, a combination of adequate pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is helpful to achieve complete remission of major depressive disorder.

Commonly used psychotherapies for depression include CBT and interpersonal therapy. CBT has been globally applied since Aaron Beck17 introduced its effectiveness on treating depression, and numerous manuals are available for formulating different goals like reduction of acute symptoms or prevention of relapse. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) was recently proven effective to prevent relapse of depression, and other modified therapies are continuously advancing.18,19 Moreover, positive psychological interventions are being tested for the treatment of depression.20,21

Traditional psychotherapy was performed through conversation between doctor and patient in the office, but modern psychotherapies also use various activities, meditation, and behavioral experiments. We suggest that a natural environment may be more effective than a gray office. Natural environments are known to positively influence human health by common sense. Environmental psychologists insist that the physical and psychological problems of modern society are associated with disconnection between human beings and their natural environment.22 Nilson23 asserted that forests provide opportunities to eliminate elements that are harmful to human health. A study from Japan showed that simply staying in, looking around, or strolling through a forest can activate the frontal cortex, lower blood pressure and blood cortisol levels, promote body relaxation, and strengthen immunity by activating natural killer cells.24

In addition to the physiological effects, environmental psychology hypotheses proposed that forests can positively influence human minds and activities. One of those is the attention recovery theory that states that human can experience recovery from fatigue in natural environments.25 According to this theory, humans are exhausted from various artificial stimulations, but nature provides a restorative environment that reduces tiredness, increases cognitive ability, and provides psychological recovery.26 Another hypothesis is that humans tend to observe or interact with animals or plants in nature, which brings treatment effects.27 Some opinions even state that nature induces coping responses rather than the defensive reactions that come from interpersonal relationships or artificial structures. According to Pryor et al.28 participants who attended a forest program showed increased confidence, subjectively better well-being, and higher self-esteem. The forest program also increased self-confidence, improved self-esteem,29 increased socialization and school attitudes,30 and effectively promoted both quantity and quality in social relationships.31

We proposed to test the effects of a forest environment as a psychotherapeutic element. Various advantages would presumably exist, including: increased movements for chronically lethargic patients; a natural and easy setting for completion of meditation techniques; and facilitated conversation with nature or colleagues. Because of these advantages, better therapeutic effects may be expected. This study aimed to reveal the effects of CBT intervention on major depressive disorder in a forest setting compared with the same intervention performed in a hospital or by usual outpatient management. Physiological parameters such as heart rate variability (HRV) and salivary cortisol concentrations were assessed in addition to changes of depressive symptoms.

Methods

Participants of the study

Seventy-three patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder at one university hospital located in Seoul participated in this study. Diagnosis was made by at least two psychiatrists based on DSM-IV-TR and was confirmed by Structured Clinical Interview for DSM disorders (SCID)32 in Korean language. Participants were selected among patients showing more than moderate severity according to the Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression (HRSD) score of above 25 before treatment with medication. All subjects were under pharmacotherapy treatment for 3 months and were relieved from acute severe symptoms but had not achieved remission and had not shown improved HRSD scores during the 2 weeks before the study began.

During the 4-week study program, all medications were maintained according to each patient's previous treatment schedule. Subjects who had any medico-surgical illnesses or any Axis I disorders other than major depressive disorder were excluded from this study.

All participants were fully informed about the study program and signed the participant agreement form. After joining this trial, each participant was assigned to the forest group, hospital group or outpatient control group according to sign-up sequence. Those who were assigned to the hospital or control groups were given the opportunity to participate in the forest program after the trial.

Initially, participants were assigned to the groups as follows: 25 in the forest group, 24 in the hospital group, and 24 patients in the outpatient control group. There was no difference in HRSD score or Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)(F=0.358, p=0.701; F=0.499, p=0.609) before starting the study. This program was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul Paik hospital (IJSP-2007-IIT-127).

Measurement of depressive symptoms

HRSD was developed by Hamilton33 for measurement of patients' depressive symptoms by clinicians. Reduction of the score to half equals treatment response and a score below 7 is defined as remission by many experts. For our study, a Korean version of the HRSD standardized by Yi et al.34 was used.

Montgomery and Asberg35 developed MADRS to improve the ability to evaluate treatment response. MADRS is a 10-item questionnaire dividing the severity into grades 0 to 6. It contains more psychological items than HRSD, which includes many physical items that mask the treatment response. In this study, a Korean version standardized by Ahn et al.36 was used.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a 21-item self-report inventory test designed by Beck37 to measure the emotional, cognitive, and physiological aspects of depressive symptoms. This study used the Korean version standardized by Song.38

Short Form Health Survey Questionnaire

SF-36 is a general health survey developed by Ware and Sherboune39 and revised by Ko et al.40 into Korean. It has 36 questions divided into 9 sections applicable to investigations about clinical studies, health policy evaluation, and the working population. It deals with general aspects including physical and psychological status that influence health. Total score is a sum of subcategory scores consisting of functional status, well-being, and overall health evaluation. Among these, functional status is a sum of 4 sections (physical functioning, social role functioning, physical role functioning, and emotional role functioning). Well-being is the sum of 3 sections (mental health, vitality, bodily pain) and overall evaluation of health is the sum of 2 sections (general health perceptions and change of health status). Sometimes, excluding the change of health status section, 8 sections are divided into 2 categories of physical health and mental health.41 Physical health is the sum of physical functioning, physical role functioning, body pain, and general health perception, while mental health is the sum of vitality, social role functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health. Every section uses Likert scale for scoring, which gives 1 point to unhealthy aspects and maximum points between 2 and 6.

Measurement of biological index

Heart Rate Variability

HRV was measured with the emWave PC Stress Relief System (HeartMath LLC, Boulder Creek, CA, USA). In a relaxed sitting position, participants waited until any interrupting waves disappeared. When repetitive clean waves consistently appeared, HRV was measured for 5 minutes.

The HRV analysis is based on the beat-to beat variation of heart beat within a certain range. Heart rate is controlled by the autonomic nervous and endocrine systems. High HRV means a condition of variable heart rate within a unit time. It is the flexibility of heart to adapt to different situations and can be used for a predictor of mortality after acute myocardial infarction.42 The most commonly used parameters include the standard deviation of 'normal RR interval (NN interval)' (SDNN) of the electrocardiogram and the root mean square successive difference (RMSSD). By Fourier transformation, basic wavelength functions could be converted to power analysis of frequency domain. Through this, total power (TP) of HRV according to the frequency domain-high frequency (HF), low frequency (LF), and very low frequency (VLF)-are acquired. It is known that HF power reflects parasympathetic activity and that the LF/HF ratio reflects sympathetic activity.43 Although the limitations of individual difference and variation between measurements exist, HRV is widely used because it can non-invasively measure responses of the autonomic nervous system.

Salivary Cortisol Concentration

A commercial kit was used to determine salivary cortisol concentration by ER HS Salivary Cortisol (Salimetrics, State College, PA, USA). Participants were asked to chew a cotton ball with their molars for at least 1 minute and the collected cotton specimens were stored in the refrigerator until use. Saliva was soaked out by centrifugation at 2,500 r.p.m. for 2 minutes. After addition of 25 µL test reagents into the saliva, 100 µL enzyme conjugate solution was added. After tapping the well-shaped groove for 5-10 seconds, light was eliminated and the enzymatic reaction was performed at room temperature with gentle shaking at 500-700 r.p.m. for 10-15 minutes. The absorbance at 450 nm was read with an E Max Precision microplate reader (Molecular Device, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Schedule of assessment and treatment programs

Participants of each program attended once a week according to the study design. The forest program proceeded at the Hong-Reung arboretum for 4 weeks with weekly 3-hour sessions, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. on Wednesdays. The Hong-Reung arboretum is a forest garden with a total of 440 thousand square meters of acicular trees, broad-leaf trees, shrubs, herb gardens, and alpine plants. It has a display of 20 thousand plants classified into 157 branches and 2,035 species and 4,245 collections of fossilized leaves and specimens. It is an experimental forest that was established for collecting and managing of plant resources and performance of forestry research. The hospital program proceeded for 4 weeks with weekly 3-hour sessions every Thursday in the room of Seoul Paik Hospital with the same format as the forest program. Sessions of each group were performed and evaluated by two master's-level psychologists following the same manual. The control group was treated with usual outpatient management. HRSD, MADRS, and BDI were measured weekly, and SF-36 was evaluated only in the first and last week. HRV and salivary cortisol were measured at 10 a.m. on the first and last weeks' sessions.

Contents of the treatment programs

CBT is a structured treatment method with various techniques made by the assumption that cognitive distortions causes negative thoughts in depression. Our program was designed to use the forest environment as a mediator of CBT by facilitating patients to reflect their problems and try to reconstruct cognitive error after strolling in the forest or hearing stories about trees. Behavioral intervention was implemented to stimulate the vitality of patients with decreased activity levels that needed implementation of mediator-stimulated drive. Both the forest and the trees were actively used for this purpose.

Mindfulness meditation is a form of insight meditation, maintaining awareness of the moment. Respiratory mindfulness meditation, which is easily applicable to the general public, observes an individual's breathing sensations without judgment and makes it possible to feel his mind as it is and induce physiological relaxation. Our program used this meditation technique by focusing on breath, wind in the forest, and sounds.

The concepts of positive psychology were introduced to improve participants' quality of life. Seligman et al.21 reported that methods to get positive emotions include 'talking about three things that were good today', 'gratitude to others', and 'using my strengths', all of which bring happiness and decrease the depressive mood. Our programs used the 'gratitude to others' and 'using my strengths' components.

The hospital program was performed in the same way as the forest program but in an indoor setting. For example, forest observation was substituted with watching window scenery or objects in the room, and use of forest objects was substituted with use of other objects or imagining something good during meditation.

Statistical analysis

The demographic data of participants (forest program group, hospital program group, outpatient control group) was compared by independent t-test. Repeated measures of analysis of variance (repeated ANOVA) were used to compare the symptomatic improvement of depressive symptoms before and after the program. Post hoc analysis for group difference was verified by Bonferroni's method. Group difference of remission induction was compared by χ2 test. Paired t-test was used for HRV, salivary cortisol concentration and change of SF-36.

Results

General characteristics of participants

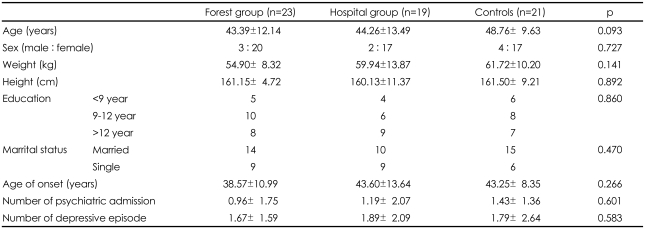

Of the initial 73 participants, 23 in the forest group, 19 in the hospital group, and 21 in the outpatient control group completed the whole program. Two patients dropped out of the forest group: one developed a rash caused by an insect bite on forest and withdrew consent; the other missed one session due to personal circumstances. No patients dropped out of the other groups due to side effects.

Demographic characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1. There was no group difference in demographic characteristics or age of depression onset (Table 1).

Changes of depressive symptoms

Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression

Analyzed by repeated measures of ANOVA, HRSD score decreased in a time-dependant manner (F=43.16, p<0.01). Group differences existed (F=3.95, p<0.05), which suggests a difference of effectiveness between programs.

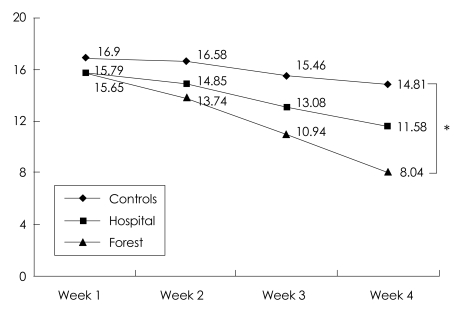

The change in mean HRSD score before and after performing the program was 15.54 to 8.04 in the forest program; 15.79 to 11.58 in the hospital group; and only minimally decreased from 16.90 to 14.85 in the outpatient control group. By Bonferroni post-hoc test, a difference between forest and outpatient group existed (p<0.05) but was not seen in either the forest group vs. hospital group or the hospital group vs. outpatient control group (Figure 1).

The change of HRSD scores in forest group, hospital group, and controls during 4 week program. The repeated measure ANOVA showed a significant time effect (F=43.16, p<0.001) and a significant between-group effect (F=3.95, p=0.025). *Post hoc analysis showed only the difference between forest group and controls, p=0.020. HRSD: Hamilton Rating Scales for Depression, repeated ANOVA: repeated measure of analysis of variance.

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scales

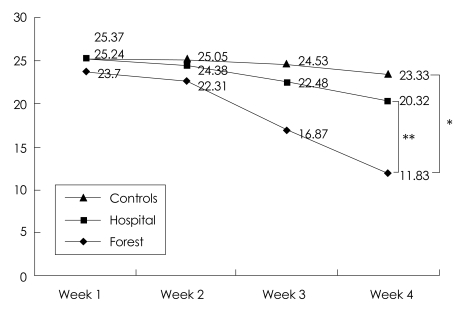

By repeated measures of ANOVA, MADRS decreased in a time-dependant manner (p<0.01). A group difference was also seen (p<0.01). Mean MADRS scores changed from 23.70 to 11.83 in the forest group, 25.37 to 20.32 in the hospital group, and only minimally from 25.24 to 23.33 in the outpatient control group. Bonferroni post-hoc test showed meaningful differences between the forest group and both the outpatient control group (p<0.01) and the hospital group (p<0.05) were meaningful. The forest program more effectively improved MADRS scores than did the hospital or outpatient control programs (Figure 2).

The change of MADRS scores in forest group, hospital group, and controls during 4 week program. The repeated measure ANOVA showed a significant time effect (F=43.25, p<0.001) and a significant between-group effect (F=5.69, p=0.005). *Post hoc analysis showed not only the difference between forest group and controls (p<0.007), **But also the difference between forest group and hospital group (p<0.048). MADRS: Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scales. repeated ANOVA: repeated measure of analysis of variance.

Beck Depression Inventory

Repeated measures of ANOVA showed a time-dependent improvement of BDI score (p<0.01), but no group difference existed.

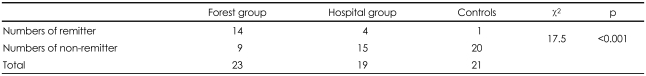

Remission Induction Rate

As previously described, no difference existed in HRSD score between the forest and hospital groups. Instead, we compared the ratio of remission induction determined by an HRSD score less than 7. The number of patients reaching remission was 14 of 23 (61%) in the forest group, 4 of 19 (21%) in the hospital group, and 1 of 21 (5%) in the outpatient control group. Significant differences existed between groups (p<0.01), and the Bonferroni post-hoc test showed that the forest group was more effective in inducing remission than hospital group (p<0.05)(Table 2).

Biological index

Heart Rate Variability

Among the various HRV indices, the 4-week forest program increased SDNN, RMSSD, and TP, which are parameters of the total amount of HRV (p<0.01; p<0.05; p<0.01). HF, the index of parasympathetic tone, also increased (p<0.05). In the hospital group, only normalized HF increased, and no positive result was found in the outpatient control group (Table 3).

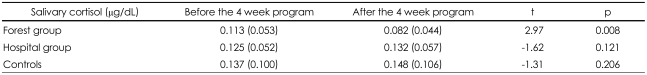

Salivary Cortisol Concentration

Mean salivary cortisol concentration decreased from 0.113 µg/dL to 0.082 µg/dL after the 4-week forest program. The other programs did not show an effect, changing from 0.125 µg/dL to 0.132 µg/dL in the hospital group and from 0.137 µg/dL to 0.148 µg/dL in the outpatient control group (Table 4).

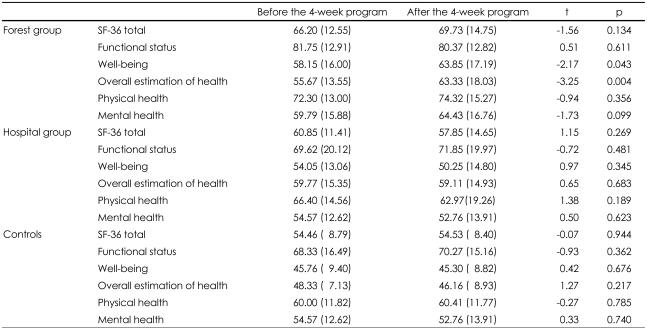

Routine health condition and health recognition scales

Total scores of SF-36, measuring general health conditions and wellness, did not show any group differences. In subcategories, subjective well-being and general assessment of health was increased in the forest group but no difference was found in the other groups (Table 5).

Discussion

This study shows that the 4-week forest program improved depressive symptoms and effectively induced remission in patients taking medication for at least 3 months. Symptomatic improvement measured by mean HRSD score decreased from 15 to 8 in the forest group, which was better than the control group. Also, the remission rate, an important therapeutic goal defined by HRSD scores lower than 7, was higher in the forest group (14/23). This was a significant difference showing that CBT delivered in a forest environment is more effective than regular outpatient treatment or CBT delivered in the hospital. Also, the 60% remission rate in our study, which included a combination of CBT and medication, was even better than clinical studies showing 30-40% of remission rate after 8 weeks of antidepressant medication.13

MADRS scores were even better. The forest program resulted in a reduction of more than 10 points, which was significantly better than the other groups. MADRS is more useful in evaluating psychological symptoms compared to HRSD, which focuses on physical conditions. The MADRS scale is more frequently used to evaluate the effects of medical treatment because psychological changes are the core symptoms of depression, and although physical illnesses are also important, they usually respond chronically. So an improved MARDS score means that the forest program has effectively improved the psychological symptoms of depression.

Parameters of HRV, including SDNN, RMSSD, RP and HF, were increased by the forest program. Time domain (SDNN and RMSSD) and frequency domain (TP) parameters indicates the total amount of HRV. A higher value means that the autonomic nervous system is well regulated and generally low stress is loaded to the heart. The forest program increased parameters of HRV which is interpreted to mean well regulated autonomic nervous system tone. This was consistent with a study showing that the forest environment is helpful in increasing HRV24 and a study comparing HRV during mounting and tower climbing.44 Parasympathetic tone was also increased according to changes in HF score. The LF, LF/HF ratio, and index of sympathetic tone increased but without significance. If the sympathetic tone increases while HRV decreases or does not change, it could be seen as a stressful situation, but if the total amount of HRV increases, it is interpreted as a refreshing and useful stimulation because parasympathetic tone has also increased. Meanwhile, the change of HRV in the hospital program was not significant but sympathetic tone increased according to the normalized HF score. No changed was detected in the outpatient control group.

The forest program, but not the hospital or control program, reduced salivary cortisol concentration, a biochemical index of stress. Although it has wide diurnal and individual variation, it is widely accepted because finding of a better alternative is difficult. A study on Japanese college students showed that activities in the forest decrease salivary cortisol concentrations more than activities in the city.24 We assume salivary cortisol concentration decreased because the forest environment lessened the stress response of participants or improved depressive symptoms.45 It is known that cortisol concentrations increase in major depressive disorder. An interesting report showed that frequently relapsing patients have high cortisol concentrations, even after symptoms improved with treatment.46 The decrease of cortisol concentration may be a biological reflection of symptomatic improvement of depression.

No group differences were found in the total SF-36 score, measurement of general health status. In SF-36 subscales, subjective wellness and general assessment of health improved in the forest group, but the improvement in functional level was not significant. Subscale differences were not found in either the hospital or the control group. We presumed two reasons why functional level and SF-36 total score had not changed in the forest group: First, it would be difficult to make an objective interpretation about an individual's own physical and psychological status in a self-assessment test, and increased subjective well-being and general health status evaluation scores support this notion. Second, 4-week treatment adequate for obtaining symptomatic improvement but may not be long enough to ensure functional improvement of depressive symptoms.

In summary, 4 weeks of a forest activity program effectively improved depressive symptoms in patients taking antidepressant medication. The effect was superior to usual outpatient management. For MADRS score and remission rate, it was better than the program performed in hospital. Physiological indexes such as HRV and Salivary cortisol also showed the superiority of the forest program to the hospital program and usual outpatient management.

Recently the importance of remission has been emphasized because remission failure causes frequent relapse and poor prognosis, which disturb patients' functional and social adaptations.7,8 Pharmacotherapy alone does not seem to be good enough to reach the goal of complete recovery of social and occupational function. Patients tend to hardly escape from functional impairments because they feel afraid to return to their routine lives, and staying at home being lethargic has already became a habit even though depressive symptoms have improved. An optimized treatment method combining pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is required for a better outcome. This is the same reason why rehabilitation is continuously needed after acute musculoskeletal disease, or why CBT to treat avoidance symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder is required even after physical symptoms have improved through use of medications.

To maximize the therapeutic effect, it is important to optimize the content and form of psychiatric management according to the disease characteristics. An environment like a hospital or forest in which psychotherapy is conducted is not just a place, but in itself is a content and form of therapy that interacts with various other factors and possibly changes outcomes. We assume some reasons why the forest is better than the hospital as an environmental element. Most importantly, patients can interact with a multitude of integrated factors including sensory stimulations of vision, smell, sound, and touch coming from the forest and trees, fresh air and wide open space, comfortable temperature, and humidity. Even patients who do not like to move autonomously in buildings can become more active in the forest. Increasing activity is important for functional recovery in depressed patients, which has been shown in studies about the usefulness of walking in anxious or depressed patients47 and in opinions about the importance of behavioral activation in CBT.48 For this reason, programs or workshops with practical approaches in an interactive environment may be better than simple advice or education telling patients to increase their activity levels. A forest environment can also facilitate interaction of psychological as well as physical activities. People can easily meditate or reconsider interpersonal problems while in the forest setting. In the hospital setting, patients often resist or avoid opening their minds, but the forest makes them speak out easily or connect with themselves through an object in nature. Therefore, interacting with the forest environment increases physical and psychological activities, which may have resulted in the therapeutic effects observed in this study.

This study also had some limitations. It was hard to generalize our results because of the limited numbers of participants. Well-controlled, large scale trials are needed to generalize the effects of the forest on human mental health. The subjects were sequentially assigned to 3 different groups, and were not fully randomized. But, these environmental interventions cannot be blind to the therapist and the subject. We also have the limitation that we did not assess patients' motivations. Motivation is an important treatment factor for patients with depressive disorders, and may affect the decision of participation in this study and the treatment results. In the future, supplemental research will be required. Studies comparing natural environments other than the forest will also be required.

As far as we know, this was the first report in Korea studying forest environment as a therapeutic modality on patients with major depressive disorder applying medical model on patients. It is widely accepted that the cost for the rehabilitation of chronically ill patients including major depressive disorder is a huge problem. For complete remission from major depressive disorder, pharmacotherapy should be combined with psychotherapeutic interventions, and use of adequate environmental elements like the forest may improve treatment outcome.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out with the support of 'Forest Science & Technology Projects (Project No. S110709L030110)' provided by Korea Forest Service.