Antidepressant-Induced Sexual Dysfunction among Newer Antidepressants in a Naturalistic Setting

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Antidepressants used to treat depression are frequently associated with sexual dysfunction. Sexual side effects affect the patient's quality of life and, in long-term treatment, can lead to non-compliance and relapse. However, studies covering many antidepressants with differing mechanisms of action were scarce. The present study assessed and compared the incidence of sexual dysfunction among different antidepressants in a naturalistic setting.

Methods

Participants were married patients diagnosed with depression, per DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, who had been taking antidepressants for more than 1 month. We assessed the participants via the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and assessed their demographic variables, types and dosages of antidepressants, and duration of antidepressant use via their medical records.

Results

One hundred and one patients (46 male, 55 female, age 42.2±7 years) completed the instruments. Thirteen were taking fluoxetine (mean dose 21.3±8.5 mg/day), 24 were taking paroxetine (mean dose 20.4±7.2 mg/day), 20 taking citalopram (mean dose 22.1±6.5 mg/day), 22, venlafaxine (mean dose 115.7±53.2 mg/day) and 22, mirtazapine (mean dose 18±8.7 mg/day). Mean ages, sex ratios, and BDI and STAI scores did not differ significantly across antidepressants. A substantial number of participants (46.5%, n=47) experienced sexual dysfunction. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction differed across drugs: citalopram 60% (n=12), venlafaxine 54.5% (n=12), paroxetine 54.2% (n=13), fluoxetine 46.2% (n=6), and mirtazapine 18.2% (n=4). Regression analyses revealed the significant factors for sexual dysfunction were being female, total scores on the BDI and SAI, and type of antidepressant (F=4.92, p<0.0001). Of the antidepressants, the mirtarzapine group's total ASEX score was significantly lower than the scores of the citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine groups.

Conclusion

The incidence of sexual dysfunction was substantially high during antidepressant treatment. The incidence of sexual dysfunction differed among antidepressants having different mechanisms of action. Our study suggests the need for clinicians to consider the impact of pharmacotherapy on patients' sexual functioning in the course of treatment with antidepressants.

Introduction

With regard to side effects, numerous clinical needs remain persistently unmet, despite the advances of psychopharmacology. Antidepressant therapy, although effective for treating the symptoms of depression, frequently induces or exacerbates the relatively common side effect of sexual dysfunction,1-5 which occurs in approximately one-half of patients. During antidepressant treatment, typical sexual dysfunction symptoms include diminished or absent libido, arousal difficulties, erectile dysfunction (in men), vaginal lubrication difficulties (in women), delayed orgasm, and anorgasmia. These sexual side effects may affect the patient's quality of life and can lead to non-compliance and relapse in long-term treatment.6

Of the newer antidepressants, venlafaxine, mirtazapine, and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) constitute the most commonly prescribed drugs. The incidence of sexual dysfunction seems to differ among these antidepressants as a result of their differences in mechanism of action. Although the SSRIs have a more favorable side-effect profile than do the tricyclic antidepressants, sexual dysfunction remains a significant problem with their use.7 A recent review suggests that between 30% and 60% of SSRI-treated patients may experience some form of treatment-induced sexual dysfunction.8 Venlafaxine is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), differing from the SSRIs in that it inhibits the reuptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine. Reportedly, the rates of sexual dysfunction with venlafaxine are lower or similar to those of SSRIs.9 Mirtazapine is unique in its mechanism of action, stimulating the release of serotonin and norepinephrine. Because it blocks the type 2 and 3 serotonin receptors, this drug theoretically produces less sexual side effects than do SSRIs.

Although many studies of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction have been conducted in western societies, there is little information on the incidence of such in Korea. Chae et al.10 reported that patients taking mirtazapine experienced significantly less side effects, in terms of decreased libido and anorgasmia, than did those taking SSRIs (35.3% vs. 64.9% and 35.3% vs. 64.9%, respectively). Though Chae et al.10 used a self-rating instrument designed to measure the subjective symptoms of patients, that instrument was not specific for the assessment of sexual dysfunction. The Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX)11 is a gender-specific, five-item self-report measure that specifically assesses sexual functioning in terms of current level of sexual drive, psychological arousal, physiologic arousal (erections or vaginal lubrication), ease of orgasm, and orgasm satisfaction. Thus, in the present study, we used the ASEX to investigate the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among depressed patients taking the newer antidepressants (citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine).

Methods

We recruited our participants from the married outpatients of the Department of Psychiatry, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital, the Catholic University of Korea. Patients were eligible if they 1) were between 18 and 50 years, 2) had a diagnosis of a depressive disorder that met DSM-IV criteria, 3) had been taking SSRI (fluoxetine, paroxetine, or citalopram), venlafaxine, or mirtazapine monotherapy for more than 1 month. We excluded patients for any one of the following reasons: diagnosis of a sexual disorder before antidepressant treatment; uncontrolled psychiatric disorder, diabetes mellitus; history of stroke, congestive heart failure, unstable cardiac condition, arrhythmia, or myocardial infarction within the last 6 months; alcohol or substance use disorder; current use of other therapies or medications to treat sexual dysfunction; and use of hormone therapy.

As mentioned, we assessed the participants' sexual functioning using the Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale.11 This scale has demonstrated internal consistency, having a test-retest reliability significant at the 0.01 level. The ASEX's sensitivity and specificity for identifying sexual dysfunction in subjects is 82% and 90%, respectively. Subjects rate their current level of sexual drive, psychologic arousal, physiological arousal (erections or vaginal lubrication), ease of orgasm, and orgasm satisfaction on a 6-point Likert scale. Ratings range from extremely positive 1) to none/never 6) for each of the five items, for a total score ranging from 5 to 30. A total ASEX score of 19 or greater, any one item with an individual score of 5 or greater, or any three items with individual scores of 4 or greater are all highly correlated with the presence of clinician-diagnosed sexual dysfunction.

For this study, two psychiatrists fluent in English translated the ASEX into Korean, and two other psychiatrists translated this Korean version back into English. The translation and back-translation procedure was repeated by four psychiatrists until they agreed that back-translation was sufficiently similar to the original scale.

We divided the ASEX item scores into subscores for 1) desire, 2) arousal, including sex drive and arousal, and 3) orgasm, including ease of orgasm and orgasm satisfaction. Then, we averaged the subscores for arousal and orgasm, each containing two items, to get a single mean score.

To control for the effect of depression and anxiety on sexual functioning, we also assessed participants using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)13 and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)14,15 and assessed their demographic variables, type and dosages of antidepressants, and duration of antidepressant use via their medical records.

The study's data analysis used the t-test or chi-square statistics, depending upon the type of variable being investigated. Among the participant groups, each using a different antidepressant, we compared the ASEX total differences and subscale scores, using ranks, by means of the Kruskal-Wallis test and the least significant difference (LSD). We used multiple regression analysis to determine which variables related to sexual dysfunction, considering a probability (p) value of less than 0.05 to be significant, and employed SAS 8.01 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) for the statistical analysis. The hospitals' institutional review boards approved this study. Each of the participants provided informed consent for their participation in this study after receiving a full explanation of the procedure.

Results

One hundred and one participants (46 male, 55 female; mean age 42.2±7) completed all instruments. Of these participants, 20 were taking citalopram (mean dose 22.1±6.5 mg/day), 13 were taking fluoxetine (mean dose 21.3±8.5 mg/day), 24 taking paroxetine (mean dose 20.4±7.2 mg/day), 22, venlafaxine (mean dose 115.7±53.2 mg/day), and 22, mirtazapine (mean dose 18±8.7 mg/day). Mean ages, sex ratios, and scores on the BDI and STAI did not differ significantly across these antidepressants (Table 1).

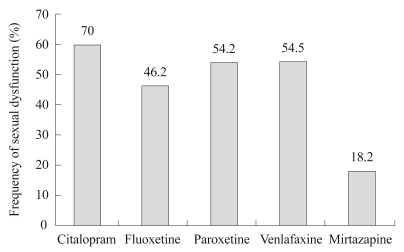

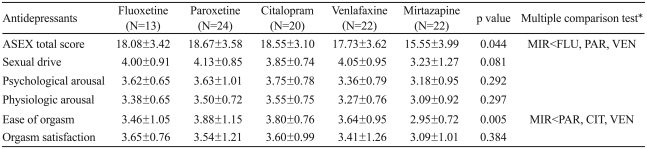

A substantial number of patients (46.5%, n=47) showed sexual dysfunction. The prevalence of sexual dysfunction differed across the drugs: citalopram 60% (n=12), venlafaxine 54.5% (n=12), paroxetine 54.2% (n=13), fluoxetine 46.2% (n=6), and mirtazapine 18.2% (n=4)(Figure 1). Regression analyses revealed that the significant factors for sexual dysfunction were gender (being female increased the probability of sexual dysfunction), total BDI score, total SAI score, and type of antidepressant (citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine increased the probability of sexual dysfunction as compared to mirtazapine)(F=4.92, p<0.0001). The mirtazapine group's total ASEX score was significantly lower than the scores of the fluoxetine, paroxetine, and venlafaxine groups (Table 2). The mirtazapine group's subscore on ease of orgasm was also significantly lower than the subscores of the paroxetine, citalopram, and venlafaxine groups (p<0.005)(Table 2).

Discussion

Sexual dysfunction associated with antidepressant treatment is not uncommon.16 Although in many cases antidepressants can improve the sexual dysfunction associated with depression, the dysfunction consequent to the medications themselves are potentially important concerns for the patient.16

In the present study, approximately half the patients taking antidepressants experienced sexual dysfunction. Comparison of the prevalence of sexual dysfunction among the participants according to the different drugs they were taking revealed relevant differences, as follows: citalopram 60%, fluoxetine 46.2%, paroxetine 54.2%, venlafaxine 54.5%, and mirtazapine 18.2%. These findings replicate the results of previous studies, which have shown both a substantial number of patients suffering from sexual dysfunction and that SSRI users experience a higher incidence of sexual dysfunction than do mirtazapine users.17

The overall incidence and the type of sexual dysfunction appear to be differentially associated among the classes of antidepressants, and also, possibly, within the classes.4,18 Tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors are frequently associated with sexual dysfunction. Other antidepressants (e.g., bupropion, moclobemide, reboxetine, mirtazapine, and nefazodone) seem to be associated with lower incidence of sexual dysfunction than the older antidepressants.4

As a group, SSRIs, venlafaxine, and mirtazpine are among the most commonly prescribed medications for controlling the symptoms of depression, due to their reduced side effect profiles, which enhance patient compliance. Nevertheless, because of their different mechanisms of action on the receptors, these medication types have different impacts on sexual functioning. Of the newer antidepressants, SSRIs seem most likely to cause sexual dysfunction. SSRIs act specifically on the serotonin system, but they also affect other monoamines. For instance, paroxetine has D2-blocking properties, thereby affecting the dopaminergic mesolimbic reward system.19 This can increase the risk of hyperprolactinemia and sexual dysfunction.20,21 In addition, paroxetine inhibits nitric oxide synthase activity, which is required for erection.22,23 In the study by Montejo et al.,17 which compared all five SSRIs, paroxetine and citalopram were associated with the highest overall prevalences of sexual dysfunction. In the present study, citalopram (60%) and paroxetine (54.2%) tended to be associated with more frequent sexual dysfunction than fluoxetine was (46.2%), though the difference was not statistically significant.

From the standpoint of sexual dysfunction, patients seem to tolerate the dual action antidepressants relatively well. The SNRIs now comprise three medications: venlafaxine, milnacipran, and duloxetine. The use of venlafaxine produces some degree of delayed orgasm, but the frequency of this is considerably lower than for SSRI use.24 In the case of milnacipran, there have been no systematic surveys. However, studies in volunteers25 have not revealed any such effects. With regard to sexual dysfunction, the difference between venlafaxine and milnacipran may be due to the former's relative selectivity toward serotonin reuptake and the latter's toward noradrenaline reuptake. Venlafaxine at low doses only blocks serotonin reuptake, whereas at higher doses (generally described as >150 mg/d), it is also a potent norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.26 At very high doses, venlafaxine blocks dopamine reuptake.26 Thus, theoretically, sexual side-effects should decrease as the venlafaxine dose increases. Because this study used relatively low doses of venlafaxine (115 mg), the sexual dysfunction frequency associated with venlafaxine was similar to that of the SSRIs.

Studies have shown that mirtazapine is associated with a low rate of sexual dysfunction. About 24.4% of mirtazapine-treated patients experience any type of sexual dysfunction.17 One of the noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs), mirtazapine is a presynaptic alpha2-adrenergic receptor antagonist, facilitating the release of norepinephrine and serotonin. However, mirtazapine's 5HT2 blocking properties reduce the potential for sexual dysfunction, particularly anorgasmia. Mirtazapine is also a potent antagonist of postsynaptic 5-HT3 receptors, which may further promote orgasm. The present study, showing mirtazapine was associated with both lowest overall sexual dysfunction frequency and greatest ease of orgasm, is in line with mirtazapine's unique mechanisms of action.

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size did not facilitate a comparison between the low-incidence adverse effects. Since response rate is generally low in surveys on sensitive topics,27,28 interpretation of the findings requires caution. Future studies need to use larger sample sizes. Second, the participants were free to take medications other than those analyzed in the study. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the incidence of side effects might have been influenced by other medications the participants were taking. Third, we did not make an initial assessment of participants' sexual dysfunction before treatment. Thus, it is difficult to distinguish antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction from the participants' remaining symptoms of depression. However, since the participants' severity of depression was mild (mean BDI score was 11.9±9.0) and improved with treatment, their sexual dysfunction may more likely be the result of medication side effects. Fifthly, a comparison with a non-depressed control group may provide more information about the medications' side effects.

In conclusion, this study suggests that sexual dysfunction often occurs with antidepressants treatment and may occur at different rates in patients treated with different medications. Clinicians should be alert to the appearance of this undesirable side effect in order to adopt the best strategy for managing depression, thus avoiding a deterioration in the patient's quality of life and possible withdrawal from the treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korean Health 21 R & D Project, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A050047).