Protective Role of Parenting Attitude on the Behavioral and Neurocognitive Development of the Children from Economically Disadvantaged Families

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Association between home environment and the behavioral and neurocognitive development of children from a community childcare center for low-income families was examined (aged 6 to 12 years, n=155).

Methods

The parents performed a questionnaire on home environment (K-HOME-Q) to assess home environment including parenting attitude and the Child Behavior Checklist (K-CBCL). The children performed the Wechsler Intelligence (IQ) Scale, Stroop interference test (Stroop), word fluency test (WF), and design fluency test (DF) to assess their neurocognitive development.

Results

‘Nurturing of Development’ and ‘Variety of Language Interaction’ scores from the K-HOME-Q, were inversely associated with total behavior problems, externalization, rule-breaking, and aggressive behavior subscales of K-CBCL, and ‘Emotional atmosphere’ and ‘Tolerance toward the child’ scores showed inverse associations with the total behavior problems, rule-breaking, aggressive behavior, and withdrawn/depressed subscales. Despite economic hardship, the mean scores of the neurocognitive tests were comparable to the average level of Korean children’s normative sample. However, ‘Nurturing of Development’ and ‘Tolerance toward the Child’ score of K-HOME-Q were associated with better executive function (IQ, WF, DF).

Conclusion

These results suggest that parental stimulation of development and tolerant parenting attitude may offer protection against the negative effects of suboptimal economic environment on children’s behavior and neurocognitive development.

INTRODUCTION

It has been widely recognized that economic hardship has a negative impact on children’s development [1,2]. Children from economically deprived families exhibit behavioral and emotional problems more often than children from families with adequate economic resources [3]. Studies have also shown associations between low income and the behavior and emotional well-being of children as young as 3 to 5 years of age [4,5]. Childhood socioeconomic circumstances are also associated with long-term effects in adulthood including physical and mental health [3,4,6]. Part of the problems caused by the children in economically deprived environment is mediated by difficulties in parental emotional well-being and decreased parenting skills [6]. Children are heavily dependent on their parents and home life as the foundation for later development [7]. The quality of parenting practices and the overall home environment plays major roles in individuals’ cognitive and non-cognitive development at the different developmental stages [1,8].

There are several hypotheses regarding how parenting mediates the development of behavior and executive function in children. The child’s temperament, ethnicity, and cultural differences modulate the effects of parenting behavior on a child’s development [9]. Biological mechanisms implicate the involvement of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis [10]. Executive functions are higher order processes, such as inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility, that enable individuals to display goal-directed actions and adaptive responses to situations [11]. The brain circuits related to these higher executive functions develop in early to late childhood and may result in behavioral control abilities or difficulties.

Not all economically deprived homes share the same general attributes. The degree and nature of the risk of particular developmental problems vary from home to home. It is crucial to specifically identify the particular risk for a given developmental problem and to plan preventive or ameliorative strategies [12]. Previous studies have shown that what parents and care-takers do with their young children makes a real difference to the children’s development and is more important than the parent’s socio-economic status or educational level. It has also been suggested that parental attitudes and behavior, particularly parents’ involvement in home learning activities, can be critical to children’s achievement and can overcome the influences of other family members and other aspects of the home environment [13].

In this study, our aim was to explore the association between home environmental factors including parenting attitude and the behavioral problems and executive functions in economically disadvantaged children aged 6 to 12 years. These children came from economically deprived families whose physical environment may not reach the national average. We questioned parents on the home environment including their parenting attitude, and physical environment. Behavioral neurocognitive tests were administered to the children to assess their executive function abilities.

METHODS

Participants

The participants were recruited from a community child center. The community child center in Korea was established to provide after-school child welfare services to children who qualify for social security, near-poverty group, and those who got a recommendation of organization which had a public confidence among can prove a family income of lower than 70% of the national average.

A total of 155 participants from community child centers in Seoul and Ulsan were enrolled in this study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of SMGSNU Boramae Medical Center (IRB No. 26-2014-41), and all study participants provided written informed consent at enrollment. The Children were administered the Korean Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition (K-WISC-III; n=149), the Stroop interference test (n=142), a word fluency test (n=142) and a design fluency test (n=152). Their mothers completed the Korean version of the Child Behavior Checklist (K-CBCL; n=149) and answered a Korean questionnaire of parenting attitude and home environment developed from Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (K-HOME-Q, n=129) by Jang [14].

Measures

Parental Questionnaire of Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (K-HOME-Q)

Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) [11] is an interview of parenting attitude and home environment performed by a rater. HOME is designed to measure the quality and extent of stimulation available to a child in the home environment. Both interaction with the parent and the physical environment are assessed by direct observation [11]. In this study, we administered an 87-item parental questionnaire developed from HOME (K-HOME-Q) by Jang [14] (Cronbach’s alpha=0.859); to measure diverse variables associated with parenting behaviors and home environment. The questionnaire was performed by the parents examined the following nine factors; 1) Living Environment Stability, 2) Nurturing of Development, 3) Variety of Language Stimulation, 4) Tolerance toward the Child, 5) Emotional Atmosphere, 6) Nurturing of Independence, 7) Variety of Experiences, 8) Physical Living Environment, and 9) Variety of Learning Materials.

Assessment of behavior: Korean Child Behavior Checklist (K-CBCL)

The Korean version of the Child Behavior Checklist [15,16] was used to assess externalizing and internalizing behavioral problems. This checklist consists of 120 questions about the child’s behavior. Parents rate how often their children exhibit each type of behavior on 3-point scale (0=not true, 1=somewhat or sometimes true, 2=very true or often true). The three categories of the Behavior problem scale (Total Behavior Problems Scale, Externalization Scale and Internalization Scale) and the nine Behavior problem syndrome subscales (Rule-Breaking Behavior, Aggressive Behavior, Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, and Other Problems) were used for analysis.

Assessment of neuropsychological development

The Korean Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition [17,18], was used to assess general intelligence. Neuropsychological tests [19] including the Stroop test, a word fluency test and a design fluency test were used to assess executive function.

Stroop test

The Stroop test is well known as a measure of selective attention and cognitive control. There are many versions of the Stroop test. This study used the Stroop test developed by Kim [19], which has been standardized for children and adolescents in South Korea. It consists of three trials. In the first trial, called the “simple task,” the subject must say the names of the colors of dots printed in colored ink (e.g., blue, red, yellow, black). In the second trial, called the “middle task,” the subject must read words (e.g., when, what, come, go) printed in colored ink. In the final trial, called the “interference task,” the subject must say the word’s color instead of the word itself, which is the name of a color other than the one in which it is printed. This test is scored according to response time. The standard score for the interference task was used in our analysis.

Word fluency test

The word fluency test was developed to assess executive functions such as conceptual mental flexibility, switch response sets and self-monitoring [20,21]. This study used a phonemic word fluency test that was standardized for Korean children and adolescents by Kim [19]. The subject was asked to say as many words as possible beginning with a given letter of the Korean alphabet within 60 seconds. Three letters (two consonants and one vowel) were used for this test. This test was scored according to the total number of correct responses. The standard score of the test was used in our analysis.

Design fluency test

The design fluency test was developed to assess nonverbal mental flexibility as a counterpart of the word fluency test [21]. This study used the design fluency test developed by Kim [19], which has been standardized for children and adolescents in South Korea. This test consists of three parts. Each part includes 35 matrices (5×7), with five dot-arrangements. The five dot arrangements were slightly different in each part. For each part, the subject was asked to draw as many different figures as possible within 60 seconds by connecting any number of five dots using straight lines. This test was scored by the total number of correct responses. The standard score of the test was used in our analysis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The characteristics of the study subjects with respect to Questionnaire of the home environment where the children are living scores were analyzed using χ2 tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. The following key covariates were used in this study: paternal education, family income and residential area. Generalized linear relationships (GLM) were modeled using the K-CBCL standard score, the K-WISC-III full-scale intelligence quotient, the Stroop interference test standard score and the word/design fluency test raw and standard scores as the outcome variables and the Questionnaire of the home environment scores as the predictor variables. Both the K-CBCL standard scores and the Questionnaire of the home environment scores were used as continuous variables.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

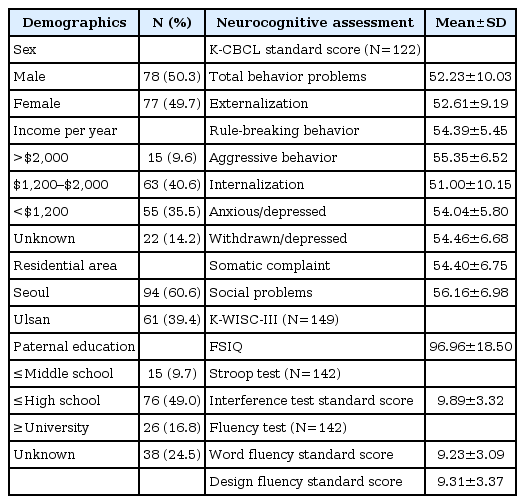

The gender and geographical distribution of the 155 subjects included in the analysis was as follows: male (n=78, 50.3%), female (n=77, 49.7%), Seoul (n=94, 60.6%); and Ulsan (n=61, 39.4%). The participants’ demographic data are provided in Table 1. The mean±standard deviation of the Stroop interference test standard score, the word fluency standard score and the design fluency standard score were 9.89±3.32, 9.23±3.09, and 9.31±3.37, respectively. There were no statistically significant differences between the 149 families included in the analysis and the 6 families who were excluded from the analysis of the children’s behavioral and neuropsychological developmental evaluation because of a lack of one of the survey items. There were significant differences between those who were included and those who were excluded from the study with respect to residential area (χ2=4.570, df=1, p<0.046), family income (χ2=94.357, df=4, p<0.001), and paternal education (χ2=50.188, df=3, p<0.001), but there were no significant differences in the gender of their children.

The Home Environment (K-HOME-Q) items endorsement frequency

The items most often endorsed by the Korean care takers about the home environment using K-HOME-Q, were ‘Reasons explained before punishment (95.3%)’ and ‘Child chooses his/her own clothes (92.2%).’ A total of 91.5% of the mothers reported that they ‘Introduce the child to visiting guests’ and 87.6% of the mothers said they ‘Check on the child when the child is in another room’ (Table 2). A total of 68.8% of the parents reported that they ‘Display the child’s drawings and art work at home’ and that there are ‘Safe play environments outside the home.’ Only 54.3% of the parents reported that the ‘Child has his/her own room.’

The Home Environment (K-HOME-Q) and Korean Child Behavior Checklist (K-CBCL)

In GLM analysis, ‘Nurturing of Development’ was inversely associated with the total behavior problems standard score (β=-1.763, p=0.001), the externalization standard score (β=-1.729, p=0.001), rule-breaking behavior (β=-0.617, p=0.049), aggressive behavior (β=-0.984, p=0.006) and social problems (β=-0.869, p=0.026) after adjusting for paternal education, family income, and residential area. ‘Variety of Language Interactions’ was inversely associated with the total behavior problems standard score (β=-1.128, p=0.027), the externalization standard score (β=-1.298, p=0.005), rulebreaking behavior (β=-0.896, p=0.001) and aggressive behavior (β=-0.861, p=0.007) (Table 3).

‘Tolerance toward the Child’ was inversely associated with the total behavior problems standard score (β=-1.440, p=0.033), the externalization standard score (β=-1.468, p=0.018), rule-breaking behavior (β=-0.885, p=0.022), aggressive behavior (β=-0.974, p=0.024) and withdrawn/depressed (β=-1.363, p=0.002). ‘Emotional Atmosphere’ showed an inverse association with the total behavior problems standard score (β=-0.694, p=0.045), rule-breaking behavior (β=-0.389, p=0.045), aggressive behavior (β=-0.590, p=0.008), withdrawn/depressed (β=-0.647, p=0.005) (Table 4) and thought problems (β=-0.500, p=0.017). ‘Nurturing of Independence’ showed an inverse association with the total behavior problems standard score (β=-1.615, p=0.018), the externalizing problems standard score (β=-1.467, p=0.020), withdrawn/depressed (β=-0.948, p=0.039), thought problems (β=-1.008, p=0.014) and other problems (β=-0.999, p=0.042). ‘Variety of Learning Materials’ was inversely associated with social problems (β=-0.805, p=0.039). ‘Variety of experience and Physical living environment’ showed no association with the K-CBCL standard score subscales.

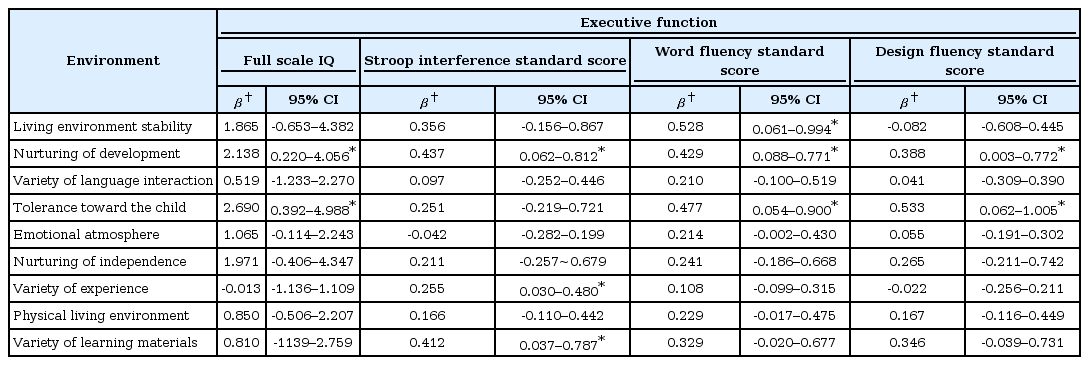

The Home Environment (K-HOME-Q) and Neuropsychological Development

In the GLM analysis, ‘Living Environment Stability’ was associated with the word fluency test standard score (β=0.528, p=0.027), and ‘Nurturing of Development’ was associated with the K-WISC-III FSIQ score (β=2.138, p=0.029), the raw score (β=1.005, p=0.008) and standard score (β=0.429, p=0.014) of the word fluency test, the standard score (β=0.388, p=0.048) of the design fluency test and the standard score (β=0.437, p=0.023) (Table 5) of the Stroop interference test. ‘Tolerance toward the Child’ showed a positive association with the K-WISC-III FSIQ score (β=2.690, p=0.022), the raw score (β=1.387, p=0.004) and standard score (β=0.477, p=0.027) of the word fluency test and the raw score (β=1.653, p=0.049) and the standard score (β=0.533, p=0.027) of the design fluency test. ‘Variety of Experiences’ was associated with the standard score (β=0.255, p=0.027) of the Stroop interference test. ‘Physical Living Environment’ was associated with the raw score (β=0.688, p=0.018) of the word fluency test and ‘Variety of Learning Materials’ was associated with the standard score (β=0.412, p=0.031) of the Stroop interference test.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we explored the association between home environment including parenting attitude, and the behavioral and neurocognitive development of children from economically disadvantaged families. The participants in this study were recruited from community child centers, which provide after-school child welfare services to children from families who qualify for social security or can prove similar economic disadvantage. The items endorsed by the care-takers reflected some of these economic difficulties. For example, only about half of the parents reported that there were ‘Safe play environments outside the home (68.8%)’, ‘The child has his/her own room (54.3%)’, and that ‘They had taken their children to a movie or the theater during the past year (55.8%).’ However, the items most often endorsed were ‘Reasons were explained before punishment (95.3%)’ and ‘The child chooses his/her own clothes (92.2%)’. Majority of the families reported that’ the child had conversations with the family during meal time (82%)’, ‘children were introduced to visiting guests (91.5%)’ and that ‘children were checked on when the children were in another room (87.6%)’. The endorsement of these and other items show that most of the parents tried to nurture their children’s independence and also tried to create a supportive emotional atmosphere despite economic hardships.

In this study, we found that the ‘Nurturing of Development’ and ‘Variety of Language Interaction’ scores were inversely associated with the total behavior, externalization, rule-breaking, and aggressive behavior subscales of the KCBCL. ‘Emotional Atmosphere’ showed an inverse association with the total behavior problems, rule-breaking, aggressive behavior, withdrawn/depressed and thought problems subscales of the K-CBCL. ‘Tolerance toward the Child’ was also inversely associated with the total behavior problems, externalization, rule-breaking, aggressive behavior subscales of the K-CBCL. Interestingly, ‘Variety of Experiences’, ‘Variety of Learning Materials’ and ‘Physical Living Environment’ showed no association with the K-CBCL externalization or the internalization subscales.

Positive parental interactions have been reported to foster sustained growth in inhibitory control and cognitive flexibility [22], which all contribute to mitigating externalizing and aggressive behavior. Sensitive care-taking was reported to promote the internalization of regulatory functions in a child [23], which may be important in the suppression of externalization and rule-breaking behaviors. Another study reported that lack of parental warmth and parental hostility were the most predictive of behavioral problems [7]. These findings are in line with previous findings that expressions of anger and annoyance, physical punishment and intrusiveness have the most significant impact on a child’s externalizing behaviors [24-26]. A more supportive presence, higher positive regard, and lower hostility from the parents were also associated with less externalization and aggressive behavior in their children [24-26]. Furthermore, a study on adopted children showed that the home environment was associated with hyperactive/impulsive symptoms in both children with attention-deficit hyperactivity (ADHD) and their non-ADHD siblings [27].

It is difficult to determine the precise relationship between socio-economic status and mental health problems, including behavioral problems in children. Substantial reports indicate that children from low-income families more often manifest symptoms of psychiatric disturbances, maladaptive social functioning and poor cognitive performances compared with children from more affluent circumstances [9]. The interactive influences of various genetic and epigenetic susceptibilities modulate the environmental influences of parenting attitude and behavior, and future studies that investigate these interactions among various factors in relation to the development of a model of the emergence of developmental psychopathology are warranted.

The results of this study also show that mean scores of the FSIQ and most of neurocognitive tests given to the subjects were comparable to the average level of a Korean normative sample [18], despite the economic circumstances. However, we observed that parental ‘Nurturing of Development’ and ‘Tolerance toward the Child’ were associated with higher IQ scores and better executive function as measured by the standard scores of the Stroop interference task, the word fluency test and the design fluency test. This result suggests that economic disability by itself has less effect on the cognitive development children compared to positive parental interactions. The executive function and social development of children are strongly linked to factors in the home environment [28,29], especially Parental Warmth, Learning Stimulation, Access to Reading, and Outings/Activities subscales measured by the HOME, had significant associations with children’s cognitive outcomes [7]. Reports have also shown that parental stimulation of a child’s learning mitigated the effects of prenatal smoking exposure on the child’s executive function development [30], suggesting indirect mediating effect of parenting on children’s cognitive development.

The results of this study show that parental sensitivity and stimulation, rather than physical environment e.g. learning materials, are associated with behavioral and neurocognitive development, suggesting that parental stimulation of development and tolerant parenting attitude, may offer protection against the negative effects of suboptimal economic environment on children’s behavioral and neurocognitive development.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Mental Health Research & Education, the Seoul National Hospital, Republic of Korea.