A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Applicability of Web-Based Interventions for Individuals with Depression and Quality of Life Impairment

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to determine the applicability of web-based treatment programs for individuals with depression and quality of life impairments.

Methods

We conducted database and manual searches using imprecise search-term strategy and inclusion criteria. Research published from 2005 to December 2015 was included in this study. Upon review, a total of 12 published papers on web-based intervention for individuals with depression were assessed eligible for this meta-analysis. Effect sizes were estimated for depression and quality of life.

Results

The mean effect size of web-based treatment on depressive symptoms was 0.72. However, unlike the result showing medium to large effect size, the analysis on the quality of life did not yield adequate effects of web-based interventions.

Conclusion

Our results suggest robust benefits of employing web-based treatments for depressive symptoms. However, the adequacy of these relatively new intervention tools for individuals who suffer severe impairments of quality of life was found insufficient. The current study demonstrates the need to further develop web-based intervention techniques to improve overall functioning, as well as the clinical symptoms of patients with mental disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with depression exhibit markedly decreased interest or pleasure in all daily activities, weight gain or loss, sleep problems, cognitive impairments, fatigue or loss of energy, and suicidal ideation [1]. That these symptoms can easily intensify or recur and reduce the daily function [2] render timely and steady interventions critical for patients with mood disorders [3].

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a form of psychotherapy, is a representative evidence-based therapy that has proved its therapeutic effect on mood disorder patients [4]. The effectiveness of psychotherapy in depression treatment was found comparable to those of psychiatric medication, which is one of the primary treatments [5,6]. Adequate and judicious interventions, however, remain inaccessible to a significant portion of psychiatric population, where in low income, geographical distance, and stigmatization pose major challenges [7,8].

Since the 2000s, the advent of easily accessible personal computers and smartphones fostered the emergence of web-based therapy as a new form of treatment for patients who cannot afford treatment due to economic or geographical reasons [9,10]. Currently available web-based intervention efforts take various approaches, such as Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Psychoeducation, and Mindfulness [10,11]. The ways to access these programs are also various, extending beyond the web sites to email correspondence, chat rooms, video chats, and mobile applications. These facets confer major advantages upon web-based interventions, allowing individuals to customize both the soft and hard contents according to his or her needs and to seek help without worrying the social stigma [12-14]. In addition, most web-based therapies yield significant symptoms improvements in patients and demonstrate effectiveness [15,16]. For instance, delivery of psychoeducation by web-based program was found to significantly decrease depression and anxiety symptoms in depressed patients [10].

However, findings on the effectiveness of web-based intervention are difficult to generalize. For example, a study compared the effects of web-based psychotherapy and face-to-face treatment program in depressed outpatients and found the former to demonstrate less effect on symptom alleviation than the latter [17]. The authors explained the superior treatment efficacy of face-to-face intervention with possibly enhanced rapport, motivations, and treatment compliance managed by the interpersonal, direct contact. In addition, meta-studies of the effectiveness of web-based therapy focusing only on symptom changes do not meaningfully address whether the decrease in symptom reflects changes in life quality. Poor quality of life is one of the most disabling aspects of depression [18]. A multi-center study on quality-of-life dysfunction reported severely impaired quality of life in the majority of depressed patients [19]. Fortunately, depression-related decrease in quality of life seems to be reversible, in that a significant improvement after appropriate treatment has been demonstrated even in patients with chronic depression [20]. The necessity and importance of incorporating “quality of life” in mental-health treatment settings are well represented in the World Health Organization (WHO)’s definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [21]. In web-based therapy, too, effectiveness needs to be demonstrated beyond the limited scope of solely focusing on symptomatic relief and extend to the accompanied changes in quality of life.

Therefore, the present meta-analysis examined the effectiveness of web-based intervention. The scope of this metaanalysis covered studies conducted between the years 2005 and 2015 that implemented depression scale scores and quality of life as outcome measures. Our study objectives were first, to provide meta-analytic evidence for the effectiveness of web-based psychotherapy on improving symptom and quality of life for depressed individuals. Second, to systematically review the clinical implications and limitations of web-based intervention demonstrated in the extant literature and to suggest practical directions for future developments of this new generation method of intervention.

Methods

Database and search strategies

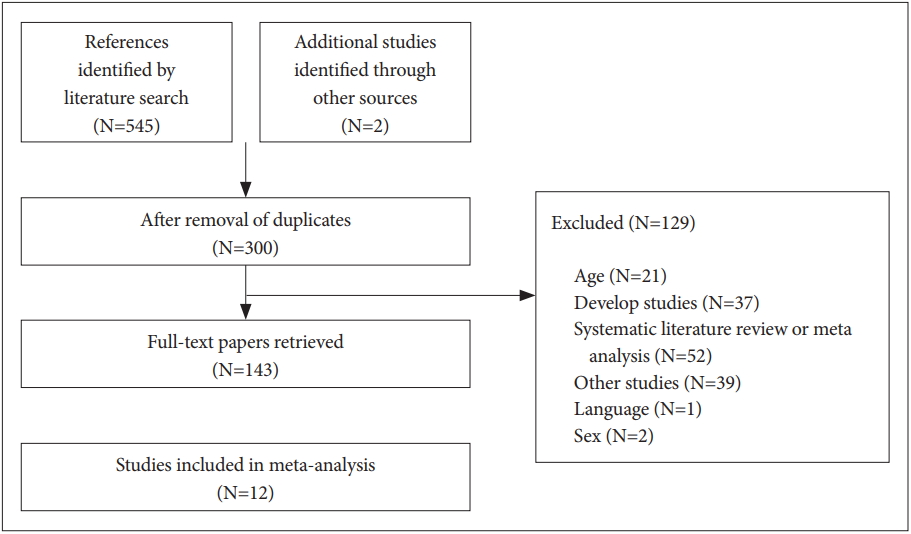

A systematic search was conducted using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, PUBMED, PsyARTICLES, PsycINFO. Extraction and assessment processes were independently conducted by three trained investigators (DY, YB, JL). The investigators first independently reviewed titles and abstracts, and the ensuing second independent review was conducted based on the full-text article. Discrepancies regarding study eligibility were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (SC or JH). We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement in reporting this review [22]. In order to identify studies examining the relevant issue, following keywords were used in combination: Depression, Depressive, Depressed, Treatment, Therapy, Intervention, Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), Web, Internet, Online, Smartphone, Android or SMS. Lastly, we conducted a comprehensive grey literature search and manual searches in the reference lists from included articles and relevant review articles to identify papers missed in the database searches.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were determined following Participants, Interventions, Comparator and Outcomes (PICOS) [23]. Inclusion criteria for the present study were as follow: 1) study population of adults who were at least 18 years old, 2) diagnoses conferred with diagnostic criteria or clinical scales, 3) psychological interventions protocol utilized computer or smart phone based delivery, 4) presence of control group with TAU (Treatment As Usual) or Wait List Control (WLC) status, 5) randomized controlled trial, 6) comparative analysis, 7) outcome variables included depression symptoms and quality of life, and 8) a peer review paper written in English.

The exclusion criteria employed were as follow: 1) the use of CD-ROM programs that did not use the web, 2) the use of a group that appealed to subjective depression without objective measures, and 3) research that may lead to bias in results by conducting research only on specific gender.

Data extraction

One investigator extracted data from candidate articles independently, and the other investigators crosschecked the extracted data. Data, including research design, diagnostic criteria for subjects, the characteristics of the sample, intervention format, and research results, were extracted from the selected articles for the meta-analysis. If necessary, authors were contacted to request of any missing data.

Data analysis

The statistical procedure in the meta-analysis follows the general statistical analysis methods. In our analysis, effect sizes were estimated from each research to determine the effectiveness of web-based intervention on the clinical symptoms and the quality of life of individuals with depression. Then, assessments of heterogeneity and publication bias were performed in order to define the identity of summarized data. The number of sessions was excluded from the analysis because there was no correlation (p=0.192) between the variable and the decrease in depression scale scores [(baseline minus follow-up scores)/baseline scores].

First, the individual effect sizes were calculated for each of the study included in the analysis, and the mean effect size (Hedges’ g) across studies were pooled using the extracted effect sizes. We calculated overall effect sizes both with the random effects model and the fixed effects model. Here, we presented only the results of the analyses based on either fixed or random effects model according to heterogeneity (the fixed effects for low heterogeneous studies vs. the random effects for high heterogeneous). Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using I2, the percentage of the total variation. To interpret the effect size results, we adopted the Cohen’s “rules-of-thumb” as following: small, 0.20 to 0.49; medium, 0.50 to 0.79; and large, 0.80 or greater [24]. Because the meta-analyses based on the published-significant findings may overestimate the pooled effect size.

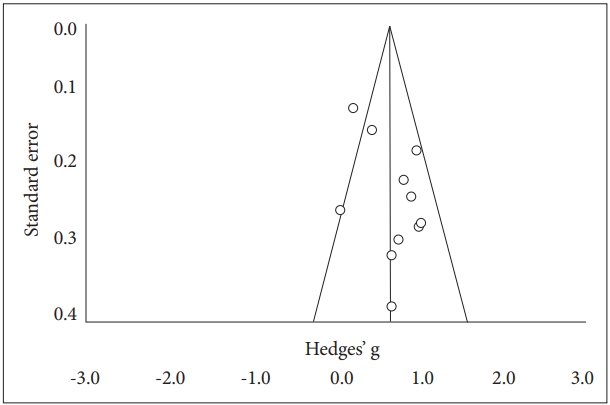

Funnel plots visualizing the possibility of publication bias were also created to prevent over-interpretation [25]. In this plot, which is most commonly used to examine the existence of publication bias in a meta-analysis, large size studies appear toward the top and smaller studies toward the bottom of the plot. When bias exists, the bottom of the plot shows a higher concentration of studies on one side of the mean than the other. Therefore, visual inspection of a funnel plot can give an indication of publication bias when the studies are non-symmetrically distributed across the pooled effect size. We performed the analysis of publication bias only for the research related to the depression not for the quality of life, because the number of studies does not suffice the requirement for performing the analysis of publication bias [26]. The overall calculations were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2011 (Microsoft Corp., Remond, MA, USA) for mac and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis 3.0 version (CMA 3.0; Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA) for windows 10.

Results

Description of included trials

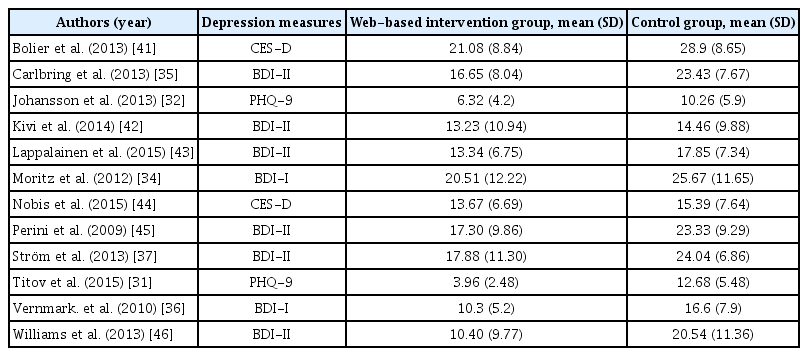

We screened 547 original bibliographic references. The flow chart illustrates the included trials, including the reasons for exclusion (Figure 1). Of the 547 papers, 300 were discarded because they were duplicated. Of the remaining 247 papers, 143 full texts were available and 12 articles on symptoms and 4 articles on quality of life met inclusion criteria and were included in the final review (Table 1).

Effects of interventions on depressive symptoms

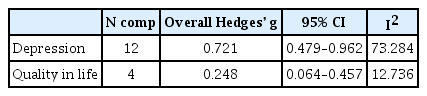

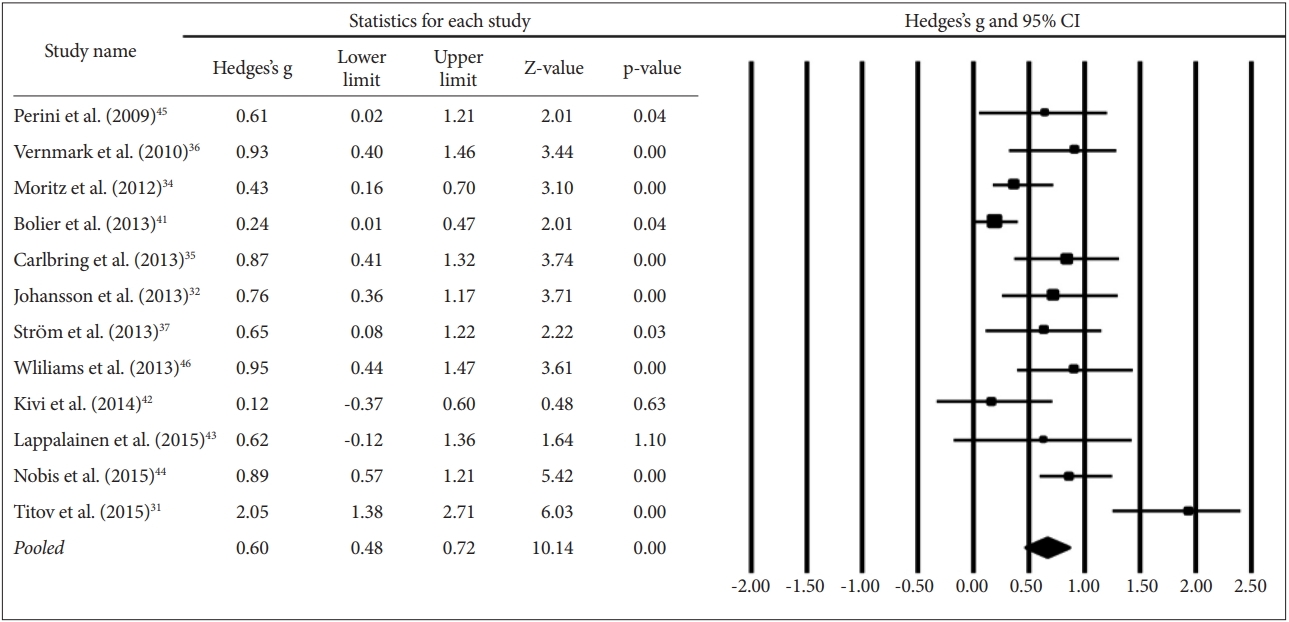

The meta-analysis of web-based intervention revealed a significantly different mean effect of Hedges’ g=0.72 (95% CI: 0.479–0.962) compared with controls. The results were based on random-effect model since the I2 statistic, the indication of the heterogeneity revealed remarkable heterogeneity among studies (I2=73.3%) (Table 2 and 3, Figure 2).

Effects of interventions on quality of life

According to the fixed-effect model based-meta analysis, there was no difference in quality of life in favor of the web-based intervention (Hedges’ g=0.25, 95% CI: 0.064–0.457). The difference in the treatment effect on quality of life was calculated using fixed-effect model when considering that there was found low heterogeneity (I2=12.7%) (Table 2 and 4, Figure 3) [26].

Publication bias

The funnel plot for depression is presented in Figure 4, and shows asymmetrically distributed studies in the bottom of the graph. As visually assessed, the slightly asymmetry funnel plot of the studies on depression suggested to consider the potential ‘file draw’ problem with unpublished papers due to the non-significant results.

Discussion

The present meta-analysis examined the therapeutic effects of web-based intervention in relation to the changes in clinical symptoms and quality of life. Our meta-analysis of peer-reviewed papers published between 2005 and 2015, demonstrated the remarkable effects of web-based intervention on reducing depressive symptoms compared to control treatments or no treatment. However, web-based intervention was found to exert no significant effect on life quality changes. Our results suggest that although the internet setting, as a new environment for psychotherapy, can offer a compelling alternative for depression treatment, its impact on daily life, as well as on life satisfaction, remains obscure.

The application of web-based therapies are being studied for a wide variety of mental disorders, including anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia as well as depressive disorder [9,27-29]. Effectiveness of these applications have been demonstrated, such as in relieving symptoms and reducing stress. With further technological advances, the availability of these new platformed interventions are expected to become even more extensive. Extant literature offers limited information on comparisons between web-based psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. However, the advantages of web-based psychotherapy was also advocated in a previous meta-analysis conducted by Hofmann and his colleagues, who compared the effectiveness of conventional psychotherapy with antipsychotics in subjects diagnosed with major depressive disorder receiving either offline CBT treatment or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [30]. Though the authors found symptoms alleviation in all subjects, side effects, such as anxiety or stress, were also reported in the medication groups. Together, these results suggest the potential strength of web-based intervention as a promising therapeutic alternative, especially when considering possible costs associated with drug treatments, such as spatial- and temporal constraints, adherence and adverse drug effects.

Furthermore, our systematic review indicated that 7 out of 9 researches employed internet-based CBT treatment and also suggested relatively better effect in web-based CBT compared to other interventions. The most prominent effect size (Hedges’ g=2.05; 95% CI: 1.38–2.72) was reported for Titov et al.’s [31] web-based CBT program. In this program, the depressed participants were asked to watch online lectures for 8 weeks on 5 topics: assertiveness communication skills, problem solving, managing worry, challenging beliefs, and sleep hygiene. In addition, all participants received 10-minutes calls or emails every week from professionals. As interpersonal contact can improve the effectiveness of web-based CBT [32], the notable impact this particular intervention had on depression may, at least partly, be due to the phone calls and emails by professionals.

The effects of a web-based treatment program demonstrated in the present study, however, were rather limited to the domain of symptom relief, and effects on improvements in facets of life quality were found inadequate. This negative result is inconsistent with the well-known positive impact that conventional CBT has on quality of life [33]. In a study comparing the proportion of patients with clinically severe impairment in quality of life, the records of depression (56–85%) were found remarkably higher compared to those of other mental disorders such as panic disorder (20%), obsessive compulsive disorder (26%), or social phobia (21%). The role of web-based CBT in the quality of life, thus, should be further elaborated by future studies and developers in relevant fields [19].

The lack of evidence found for the effectiveness in quality of life may be explained by the differences in content compositions of each web-based program. The web-based treatment devised by Moritz et al. [34] targeted a variety of psychological factors related to quality of life, such as cognitive modification, mindfulness, positive psychology and emotion-focus interventions. Intervention designed by Carlbring et al. [35], on the other hand, focused on behavioral activation (BA) and employed, acceptance commitment therapy (ACT), while Vernmark et al. [36] implemented a psychoeducational program that included therapy theory and depressive symptoms from a CBT-perspective, and Ström et al. [37] applied therapist-guided physical exercise. Though the aforementioned studies all reported no significant effect on life quality changes in depressed populations, the broad range of differences in objectives and methods evident across studies should not be overlooked. Clinical symptoms constitute only a part of the multifaceted factors that affect the quality of life of patients [38]. As such, web-based interventions heavily focusing on symptom relief may be too narrow and miss important mental health indicators. On the other hand, there is also possibility that statistically insignificant results may be derived due to the quite complex and extensive nature of the variable, quality of life. Therefore, further research is required, focusing on the details of the quality of life.

Our present results reiterate the necessity of therapeutic techniques that monitor and intervene the general adaptation level and daily functions in individuals with psychiatric symptoms. Given that the ultimate goal of all psychotherapies is to enhance life satisfaction and adaptation levels [39,40], issues related to the coverage of web-based intervention deserves much attention. The currently available web-based programs that have been in use for more than a decade may now be on the crossroads of mainstream treatment and adjunctive therapy and heading to a new era on the crossroads.

Significance of this meta-study lies in its analysis of the effects that web-based treatment program has on symptom relief and quality of life of individuals with depression, the most common mood disorder. However, several limitations of the present study also need to be considered. Our inclusion of studies limited to those reporting outcome variables both for depressive symptom relief and quality of life led to the exclusion of other various contents of the web-based treatment program. A more encompassing meta-analysis will be avail with much research on web-based psychotherapy ongoing (Clinical Trials.Gov; a service of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, https://clinicaltrials.gov/). Likewise, further research examining the details of the clinical conditions associated with successful web-based psychotherapy, such of as self-esteem or personality traits, would be of great interest. The heterogeneity across programs should also be noted. Varying numbers of sessions, durations of a single session, and participant demography across studies may impact the extent of therapeutic effect. In the present study, however, we did not make a detailed distinction based on such differences, as doing so would lead to insufficient number of studies and impact the power of analysis. With further accumulation of relevant research, the necessary subcategorization and comparison of the effects based on differential study parameters and subject characteristics would be possible.

Despite limitations, our current meta-analysis provided compelling evidence for the effectiveness of web-based intervention in relation to depressive symptom alleviation. Web-based intervention availed a new platform for psychotherapy that may complement the present depression treatment regimes by widening the scope of treatment, or may serve as a good alternative to the existing options. The tool’s promising prospects, however, yet remains in short of reaching the quality of life domains. Findings from the present meta-analysis advocate the necessity of expanding the scope of web-based intervention approaches by developing various intervention modules. In order to give practical assistance to users, future developments in the field should carry methodological rigor, while, at the same time remain close to the everyday life.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HM15C1245).