Frontal Alpha Asymmetry, Heart Rate Variability, and Positive Resources in Bereaved Family Members with Suicidal Ideation after the Sewol Ferry Disaster

Article information

Abstract

Objective

After the Sewol ferry disaster, bereavement with suicidal ideation was a critical mental health problem that was accompanied by various neuropsychological symptoms. This study examined the frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA), heart rate variability (HRV), and several psychological symptoms in bereaved family members (BFM) after the Sewol ferry disaster.

Methods

Eighty-three BFM after the Sewol ferry disaster were recruited. We assessed FAA, HRV, and psychological symptoms, including depression, post-traumatic stress, post-traumatic growth factor, anxiety, grief, and positive resources, between BFM with the presence and absence of current suicidal ideation.

Results

Compared to BFM without suicidal ideation, BFM with suicidal ideation showed a higher FAA with right dominance. Significant differences in psychological symptoms were observed between the groups. In BFM with suicidal ideation, the low: high frequency (LF:HF) ratio correlated with social resources and support.

Conclusion

The FAA and LF:HF ratio may be biomarkers that represent the pathological conditions of BFM with suicidal ideation. If researched further, they may shed light on the interaction between bereavement with suicidal ideation and social resources for therapeutic intervention.

INTRODUCTION

The Sewol ferry sinking incident occurred on April 16, 2014 and was the most tragic recent accidental disaster in South Korea. The ferry was carrying 476 people and people of 304 were died by sinking accident. Most of the bereaved people were parents who lost their high school students (246 students died one of 325) who were on a school trip. Bereavement from disasters, such as ferry sinking and airplane crashes, can cause several psychiatric and physiological problems, and bereaved family members (BFM) show more severe pathological symptoms as time progresses [1]. Suicidal ideation in BFM is a serious problem that emerges after the death of a family member in a disaster. Suicide rates are higher in bereavement, and complicated grief independently predicts a suicidal ideation [2-4]. Nevertheless, the neurobiological characteristics of bereaved people with suicidal ideation are not completely understood in the context of family loss owing to disasters.

Frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) in electroencephalography (EEG) is a psychiatric biomarker [5,6] and is associated with suicidal ideation and behavior [7,8]. FAA can indicate a brain interhemispheric activity that relates to emotional and approach/withdrawal behavior [9,10]. Dominance of the left side in FAA is a biomarker of depression, which shows right and left frontal activation related to withdrawal behavior in negative emotions and approach behavior in positive emotions [11,12]. In addition, heart rate variability (HRV) has been used as a potential biomarker for psychiatric disorders [13]. HRV reflects the circadian rhythms and balance of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) in psychiatric disorders [14]. Low-frequency (LF), high-frequency (HF), and LF:HF ratio are promising indices that indicate sympathetic activity, parasympathetic tonergic activity, and sympathovagal balance, respectively [15]. Studies that have investigated suicidal ideation with FAA and HRV in disaster trauma are rare.

The present study examined the effect of suicidal ideation on FAA and HRV in BFM after the Sewol ferry disaster. We further assessed several psychological symptoms, including depression, anxiety, traumatic stress, growth factor after trauma, grief, and positive resources.

METHODS

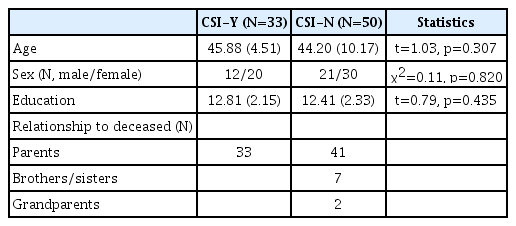

Eighty-three BFM of victims of the Sewol ferry disaster (32 men and 51 women) were recruited. The scheduling of the survey and distribution of the questionnaires were conducted with assistance from the Ansan Mental Health Trauma Center. The cohort data was collected at 18 months after the disaster. The mean age was 44.87±8.46 years (range, 19–61 years). Psychological symptoms were assessed using self-report rating scales. Participants were classified into two groups according to the presence or absence of a current suicidal ideation (CSI). There were 33 parent participants with CSI-Yes (CSI-Y) and 50 with CSI-No (CSI-N) including 41 parents, 7 brothers/sisters and 2 grandparents of victims. Each participant had lost one person in disaster. The descriptive statistics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul Saint Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea (KC15OIMI0261). All participants provided signed informed consent.

Electrophysiological measurements

Participants were seated in a comfortable chair in a soundattenuated room. A two-channel EEG device (Model: Amp AD8220) (SOSO H&C, Kyungpook University, Daegu, Korea) was used to measure the cortical activity in the frontal lobe for 5 min. in a resting state with closed eyes. The dry electrodes were secured using a headband at Fp1 and Fp2 sites, according to the 10–20 system. The reference electrode was placed on the right ear lobe. The sampling rate was 256 Hz. Online notch filtering (60 Hz) was applied. Data were reanalyzed using Matlab 2012 software (Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA), using a fast Fourier transform with a bandpass filter of 1–50 Hz to calculate relative delta (1–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), beta (12–30 Hz), and gamma (30–50 Hz) signals. Artifacts exceeding ±100 μV were rejected at all electrode sites. Thirty artifact-free epochs (epoch length 2.048 s) were obtained for each participant. To identify possible EEG-signal artifacts caused by muscle tension, a correlation analysis was performed between EEG power and scores of restlessness. Restlessness was defined in accordance with the General Anxiety Disorder checklist as “being so restless that it is hard to sit still.” No significant correlation was found between EEG power and restlessness symptoms. The FAA was calculated for the common log transformed right minus left (log10 Fp2–log10 Fp1).

HRV

The HRV was examined for 5 min during the morning (9 a.m. to noon) to prevent the influence of the circadian rhythm [16]. Electrodes were attached to the participant’s right and left wrists in a calm environment [17,18]. The standardized short-term recording of 5 min has been widely adopted because of its cost-effectiveness and convenience [19]. We used a HRV-device, the WISE-8000 (Mooyoo Instruments, Seongnam, Korea), for signal acquisition, storage, and processing. After confirming that the graph was clear and had no interfering wavelengths, the electrocardiogram (ECG) recordings were collected at a sampling frequency of 500 Hz. The ECG signal was used to define the R-R intervals for the HRV calculation. The HRV analysis was done according to the standard method described in the Task Force Guidelines [19]. Spectral analysis using a fast-Fourier transform algorithm was automatically performed to generate the heart period power spectrum. The power spectrum was divided into frequency domain measurements. LF (0.04–0.15 Hz) and HF (0.15–0.40 Hz) powers (ms2) were examined. The LF:HF ratio, which is thought to reflect the parasympathetic and sympathetic balance, was also calculated. As the LF, HF, and LF:HF ratio were not normally distributed, common log transformations were calculated.

Psychometric measurements

P4 Suicidality Screener (P4 screener)

CSI was assessed by P4 screener which includes 4-items that measure possibility for suicidality [20]. The P4 screener has a nominally-rated scale with answers of yes or no (CSI-Y or CSI-N).

Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)

Depressive symptoms were assessed by PHQ-9, where nine items are answered on a 4-point (0–3) response scale. The scores ranged from 0 to 27, and the internal consistency of the Korean version of PHQ-9 was 0.88 [21].

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Check List-5 (PCL-5)

PTSD symptoms were assessed by PCL-5, a 20-item selfreport questionnaire, in which each item is answered on a 5-point (0–4) response scale [22]. The scores ranged from 0 to 80, and the Korean version of PCL-5 showed a high internal consistency (α=0.97) [23].

Short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI-SF)

Posttraumatic growth factor was assessed by PTGI-SF with a 10-item questionnaire [24]. The Likert scale is rated on 6-points, based on the answered for, “I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis” (scored 0), to “I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of my crisis” (scored 5).”

Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG)

Grief was assessed by ICG, a 19-item self-report questionnaire, in which each item is answered on a 5-point (0–4) response scale [25]. The total scores ranged from 0 to 76, and the internal consistency of the ICG Korean version was defined by a Cronbach’s α of 0.87 [26].

Statistical analysis

We tested descriptive statistics using independent t-tests and chi-square tests between the CSI-Y and CSI-N groups (Table 1). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 (two-tailed). Psychological symptoms, FAA, and HRV were compared between both groups using multivariate analysis of variance. The within-participant factors were psychological symptoms, FAA, and HRV. The between-participant factors were the respective CSI groups. Multiple comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni correction. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed with bootstrapping (5000 times) among psychological variables, FAA, and HRV. In the correlation analysis, the statistical significance level was defined at p<0.003 according to the Bonferroni correction (0.05/15) (15 variables: LF, HF, LF/HF, FAA, PHQ, GAD, PTSD, PTGI, GRIEF, POREST1-5, and POREST-Total). The analyses were performed using SPSS 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

Significant differences were observed between the two groups with respect to FAA. Higher FAA was observed in the CSI-Y group than in the CSI-N group (F1,81=12.92, p=0.001, ηp2=0.14) (Figure 1). Symptomatic differences were also found (Figure 2). Higher pathological symptoms such as depression (F1,81=18.06, p<0.001, ηp2=0.18), anxiety (F1,81=13.11, p=0.001, ηp2=0.14), PTSD (F1,81=16.50, p<0.001, ηp2=0.17), and grief (F1,71=19.60, p<0.001, ηp2=0.22, N, CSI-Y:CSI-N=29:44) were observed in the CSIY group than in the CSI-N group. A lower optimism in POREST (F1,81=10.79, p=0.002, ηp2=0.12) was observed in the CSI-Y group than in the CSI-N group. In the CSI-Y group, the LF:HF ratio positively correlated with social resources and support in POREST (R=0.52, p=0.002) (Figure 3).

Comparison of frontal alpha asymmetry between CSI-Y and CSI-N. CSI-Y: current suicide ideation-Yes, CSI-N: current suicide ideation-No.

Symptomatic comparison between CSI-Y and CSI-N. PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire, GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder, PTGI: Posttraumatic Growth Inventory, PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, GRIEF: Complicated Grief, PO-1: optimism, PO-2: purpose and hope, PO-3: self-control, PO-4: social support and resources, PO-5: caregiving, CSI-Y: current suicide ideation-Yes. CSI-N: current suicide ideation-No.

DISCUSSION

The present study found a significant difference of FAA between BFM with and without CSI after the Sewol ferry disaster. Symptomatic differences were also observed in depression, anxiety, PTSD, grief, and positive resources. The correlation was significant between the LF:HF ratio and positive resources in BFM with CSI.

Suicidal ideation and psychophysiological changes in BFM owing to ferry disasters offer valuable information and rare clinical findings. Cortical interhemispheric activity in the alpha bandwidth is a known biomarker of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders [32,33]. It is difficult to define pathological characteristics of bereaved people as a specific psychiatric disorder. Symptomatic aspects that develop into various psychiatric problems in BFM are common. Furthermore, we need to differentiate bereavement with suicidal ideation owing to other psychiatric disorders. In a previous study, female adolescents showed a greater alpha activity in right side than in the left, in comparison to female adolescents who had an attempted suicide history [8]. Individuals with depression also showed increased frontal alpha activity in the left side, compared to right side [34]. Furthermore, it has been found that patients with schizophrenia show a left lateralized FAA, and patients with major depressive disorder display a right-lateralized FAA [32]. In PTSD, left FAA is dominant [6,32]. The BFM with suicidal ideation in our study showed a right-sided dominance in FAA, which indicated disorganized negative emotion processing related to bereavement with suicidal ideation [35]. BFM have neurophysiological characteristics that are opposite to those of patients with PTSD. While this point might imply that in this study, it was difficult to diagnose BFM as having PTSD, BFM with suicidal ideation could be defined as a homogeneous character with right-sided FAA dominance.

Higher prevalence of psychiatric symptoms such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, and grief was observed in the CSI-Y group than in the CSI-N group. Suicidal ideation is a major risk factor for mortality [36]. In addition, BFM with suicidal ideation had relatively lower positive resources. This implicates that the homogeneous psychological features of bereaved people with suicidal ideation are a representative pathological condition. In a previous study, complicated grief predicted suicidal ideation, which means that identifying suicidal ideation in grief is very useful as a therapeutic intervention [37]. The participants in our study might display aspects of secondary traumatic stress. A negative life event could induce a suicidal behavior and several psychopathological symptoms [38]. Especially, bereavement following disaster needs to be investigated over long-term interventions in the context of several mental health problems [39].

The LF:HF ratio correlated with social resources and support in the CSI-Y cohort. Patients with PTSD showed a decreased HRV as an increased of LF:HF ratio [13,40]. Although, there was no significant difference of HRV between CSI-Y and CSI-N groups, the result could imply that sympathovagal activity of participants with CSI was reflected in compensatory responses according to positive correlations between LF:HF ratios and positive resources. Social support and resources could provide a positive influence on life after disasters. Considering the severe psychological symptoms, social resources and positive support factors would protect against increased LF:HF ratio. Although BFM with CSI answered several suicidal methods for the question that if they attempt suicide, such as by gun shot, drug, car accident, falling down, burning oneself, and cut on wrist (Supplementary Table 1 in the online-only Data Supplement), the maintenance of life against suicidality was important to other family members. Therefore, suicidal ideation in bereavement is an important psychological issue that needs to be dealt with promptly, and social resources will facilitate therapeutic interventions.

Limitations

The study included a few limitations. First, healthy controls were not recruited for FAA and HRV measurements. Second, a follow-up study that uses multichannel EEG devices is needed. Third, present study was uncontrollable for pre-disaster baseline differences on key measures of interest between groups. Although we evaluated clinical symptoms, pathological diagnosis was not made clear.

Conclusions

Bereavement with suicidal ideation was associated with a relatively right dominance of FAA in BFM after the Sewol ferry disaster. The correlation between LF:HF ratio and positive resources could implicate the relationship of compensation in social support and resources and HRV. The changes in FAA and HRV could indicate neuropsychological conditions of BFM. Social resources and support is a protective therapeutic factor in bereavement with suicidal ideation.