Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms and Posttraumatic Growth Following Indirect Trauma from the Sewol Ferry Disaster, 2014

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The definition of psychological trauma, which was traditionally restricted to immediate and direct experience, is now expanding to include mediated or vicarious experience. So the present study aims to examine the relationship between the negative effects and the positive outcomes to a national disaster by assessing the posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and posttraumatic growth of the general public.

Methods

A nationwide survey of the Korean population (n=811) who were exposed to the Sewol ferry disaster through the media participated in this research, completing a self-report questionnaire consisting of demographic characteristics, Impact of Event Scale-Revised- Korean, and Korean-Stress-related Growth Scale-Revised. The participants were divided into three groups according to the severity of PTSD symptoms, then one-way ANOVA were conducted.

Results

The results revealed 30.4% of the sampled participants reported stress symptoms equivalent to partial or full PTSD. Posttraumatic growth was significantly higher in the full and the partial PTSD symptom groups when compared to the normal group [F (2, 759)=20.534, p<0.001]. At a subscale level, mature thinking showed a more significant result [F (2,759)=23.146, p<0.001] than religious growth [F (2, 180.984)=4.811, p<0.01].

Conclusion

The results indicated a general linear trend between the severity of PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth level, suggesting that indirect trauma also induces both PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth like direct trauma does. The theoretical implications based on these findings were discussed.

INTRODUCTION

With the rapid development of communication technologies, many can now experience disasters vicariously through the media in real time as well as the option to access it repeatedly, exposing oneself to indirect trauma without ever actually experiencing a disaster firsthand. Traditionally restricted to immediate experience, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is now expanding to include mediated experience [1]; the revised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth-edition [2] included an exposure to the traumatic event through the media in its diagnostic criteria for PTSD on the condition that the exposure was work related.

However, even as growing evidence suggests that the general public also experience PTSD symptoms after being exposed to traumatic events through the media [3-17], most studies have focused on pathogenic outcomes even though positive and beneficial changes following a traumatic life experience have been reported empirically.

This phenomenon of positive changes is called by a different name depending on the researcher: positive psychological changes [18], thriving [19], transformational coping [20], quantum change [21], posttraumatic growth [22], finding benefit [23], stress-related growth [24], perceived benefits [25], flourishing [26], and adversarial growth [27]. Growth does not mean the same thing as an increase in well-being or a decrease in pain [28] and is more than an adaptive effect from trauma or a return to a previous state, but growth is instead related to achieving a higher level of functioning that was not present prior to the trauma [27,28]. Throughout this study, the term posttraumatic growth will refer to these positive changes collectively.

Although less widely examined, positive changes as a result of an indirect trauma through the media have been recorded. After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, studies revealed that 57.8% of a nationwide survey perceived social benefits of September 11, including increased prosocial behavior, religiousness, and political engagement [29]. The level of trauma symptoms correlated positively with posttraumatic growth [30]. Therefore, we hypothesized that the severity of PTSD symptoms following indirect trauma through the media is associated with a level of posttraumatic growth. In order to address that research question, we evaluated the general public’s PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth from exposure to the Sewol ferry disaster through the media and then examined the relationship between each other. Because, indirect trauma through the media is unavoidable in today’s world, understanding both negative and positive effects of indirect trauma through the media is very important for the clinical field as well as everyday life.

METHODS

On April 16, 2014, 304 out of 476 passengers drowned or went missing from the Sewol ferry disaster in South Korea; the majority of the victims being young high school students (82.2%, n=250) [31,32]. Every major Korean TV station broadcasted the event in real time as the overturned ship sank in a matter of hours. Photos and videos capturing the fatal moments of the victims were restored from salvaged smartphones and broadcasted on TV and posted on the Internet for the public to consume incessantly.

Participants and procedure

The data from the nationwide survey, with ages ranging from 14 to 70 (M=31.6, SD=12.31), were collected by the researchers by convenience sampling, and the participants (male: n=327; female: n=493) signed informed consents that they were agreeing to the purpose of the study and voluntarily participating. Approximately six weeks after the Sewol ferry disaster, over a three month period, participants filled out a self-report questionnaire that included demographic characteristics, Impact of Event Scale-Revised-Korean (IES-R-K), and Korean-Stress-related Growth Scale-Revised.

Since previous exposure to trauma signals a greater risk of PTSD from a subsequent trauma [33] and cumulative traumas predict increasing symptom complexity [34], previous exposure to trauma can be a vulnerability factor to an additional traumatic event such as the Sewol ferry disaster. Therefore, participants answered to IES-R-K retrospectively to ascertain any PTSD symptoms before the Sewol ferry disaster. The study protocol was reviewed by the Review Board of Hallym University Kangnam Sacred Heart Hospital (IRB No. 2018-05-008).

Measures

Demographic information requested included age, gender, and media preferences for news and information gathering.

The severity of PTSD symptoms was assessed with the 22-item IES-R-K [35] which is the standardization of Impact of Event Scale-Revised [36]. It consisted of four factors: intrusion, avoidance, hyperarousal, and sleep disturbance, emotional numbing and dissociation. A five-point Likert scale, the response options ranged from “0=Never” to “4=Very often”. A high total score represented high severity of PTSD symptoms, so a total score of 25 or more was considered to be equivalent to full PTSD while a total score of 18–24 was considered to be equivalent to partial PTSD [35]. The coefficient α for this sample was 0.952.

The level of posttraumatic growth was measured with the 29-item Korean-Stress-related Growth Scale-Revised: K-SRGS-R [37] which is the standardization of Stress-related Growth Scale [24]. It consisted of three factors: mature thinking, affective growth, and religious growth. The response options ranged from “0=Not at all” to “2=A great deal”, a three-point Likert scale. A high total score represented a high level of posttraumatic growth. The coefficient α for this sample was 0.966.

Data analysis

SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the statistical analysis, and cases with missing values were excluded from each analyses. Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and one-way ANOVA were conducted. The participants were divided into three groups according to the cutting point of IES-R-K [35]. They were labeled full PTSD symptom group when IES-R-K score was equivalent to full PTSD (25 or more), partial PTSD symptom group when IES-R-K score was equivalent to partial PTSD (18–24), and normal group when IES-R-K score was under the cutting point (17 or less). We then conducted Scheffé’s post-hoc test because the size of the groups was different. However, when the homogeneity of variances was violated, Welch’s ANOVA and Dunnett T3 test were performed.

In order to confirm if the results can be generalized, the participants retrospectively answered IES-R-K; then those with pre-existing PTSD symptoms (18 or more in IES-R-K score) were excluded to the analysis while the rest of the sampled participants was again divided into three groups: full PTSD symptom group, partial PTSD symptom group, and normal group.

RESULTS

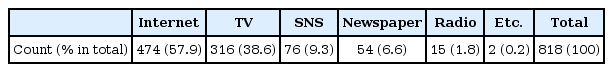

The preliminary analysis on media use presented in Table 1 showed that the general public was exposed highest to news via the internet (57.9%), followed by TV (38.6%), social network services (9.3%), newspapers (6.6%), and lastly radio (1.8%). Through this data, one can extrapolate that most of the general public was exposed to the Sewol ferry disaster through an audiovisual media.

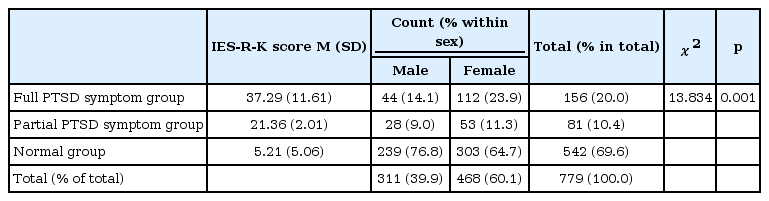

A considerable number of the sampled participants reported PTSD symptoms after their exposure to the Sewol ferry disaster through the media. Twenty percent (n=156) of participants reported symptoms equivalent to full PTSD (M=37.29, SD=11.61) and 10.4% (n=81) of participants reported symptoms equivalent to partial PTSD (M=21.36, SD=2.01) according to the IES-R-K score (Table 2). There was also a significant difference in PTSD symptoms following indirect trauma according to gender. Females were more affected by indirect trauma than males, which is consistent with previous studies [38-41].

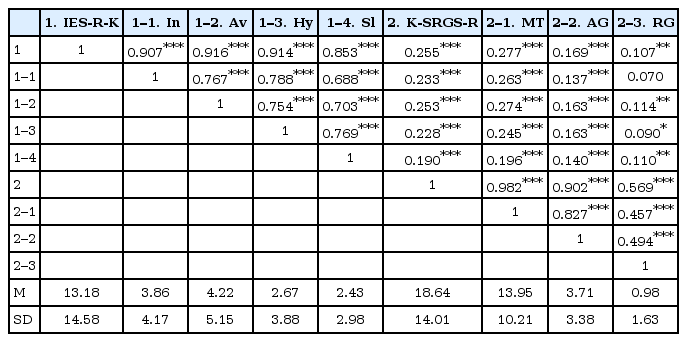

As presented in Table 3, preliminary analysis included Mean, Standard Deviations, and the correlation between PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth. A positive correlation was significantly indicated between the scores of K-SRGS-R and IES-R-K (r=0.255, p<0.001). These correlations also determined that PTSD symptoms following indirect trauma were associated more strongly with mature thinking (r=0.277, p<0.001) than affective growth (r=0.169, p<0.001) or religious growth (r=0.107, p<0.001).

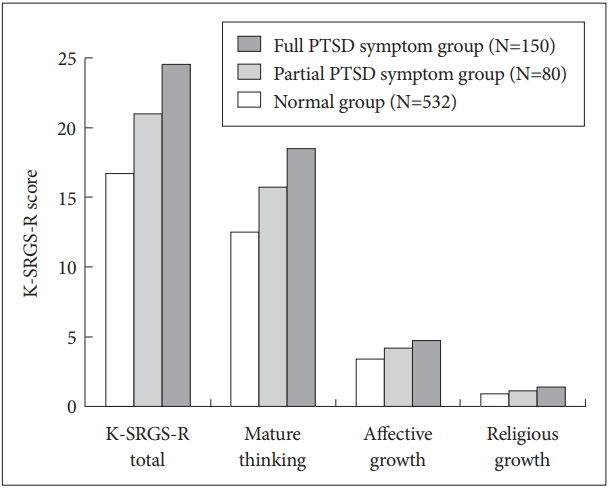

The ANOVAs showed a significant linear trend of PTSD symptoms with posttraumatic growth, resulting in a significant difference of K-SRGS-R score at the p<0.05 level for the three groups, F (2, 759)=20.534, p<0.001. Post hoc comparisons using the Scheffé’s test indicated that the mean score for the normal group (M=16.65, SD=13.67) was significantly lower than the partial PTSD symptom group (M=20.91, SD=13.03) and the full PTSD symptom group (M=24.49, SD=13.95). However, the full PTSD symptom group and the partial PTSD symptom group were not significantly different from each other. This trend was replicated across the growth subscales and subanalyses (Figure 1).

Posttraumatic growth level by the severity of PTSD symptoms. K-SRGS-R: Korean-Stress-related Growth Scale-Revised, PTSD: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

There was also a significant difference of mature thinking at the p<0.05 level for the three groups, F (2, 759)=23.146, p<0.001. Post hoc comparisons using the Scheffé’s test indicated that the mean score for the normal group (M=12.42, SD=9.94) was significantly lower than the partial PTSD symptom group (M=15.70, SD=9.56) and the full PTSD symptom group (M=18.47, SD=10.08). However, the full PTSD symptom group and the partial PTSD symptom group did not show significant difference from each other. There was also a significant difference of affective growth at the p<0.05 level for the three groups, F (2, 759)=9.676, p<0.001. Post hoc comparisons using the Scheffé’s test indicated that the mean score for the full PTSD symptom group (M=4.67, SD=3.61) was significantly higher than the normal group (M=3.37, SD=3.32). Still, the partial PTSD symptom group (M=4.15, SD=3.00) did not significantly differ from the full PTSD symptom group and the normal group. Welch’s ANOVA showed that there was a significant difference of religious growth at the p<0.05 level for the three groups, F (2, 180.984)=4.811, p=0.009. Post hoc comparisons using the Dunnett T3 test indicated that the mean score for the full PTSD symptom group (M=1.35, SD=1.76) was significantly higher than the normal group (M=0.86, SD=1.59). However, the partial PTSD symptom group (M=1.06, SD=1.54) did not significantly differ from the full PTSD symptom group and the normal group. These results indicated that the level of posttraumatic growth was significantly higher in the groups with PTSD symptoms compared to the normal group.

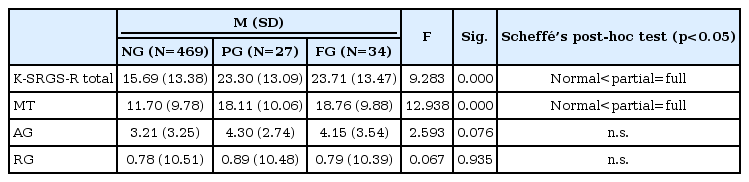

In order to make sure if the results can be generalized, the data were analyzed again after excluding participants who already had pre-existing PTSD symptoms. The results were similar to those of the previous analyses; the normal group reported the least posttraumatic growth (Table 4). K-SRGS-R total score and mature thinking had a positive correlation with the severity of PTSD symptoms [F (2, 527)=9.283, p<0.001, F (2, 527)=12.983, p<0.001] while affective growth and religious growth did not have any significant correlation.

DISCUSSION

The findings of this study concluded that 30.4% of the participants reported posttraumatic stress symptoms equivalent to full or partial PTSD. The Sewol ferry disaster was a huge shock not only to the victims and their families but also to the general public. These findings are in accordance with the other researches on national disasters such as the September 11 terrorist attacks [7,10]. The data from the current study was collected six weeks after the Sewol ferry disaster occurred over a period of three months, so the results implied that PTSD symptoms of the general public due to a national disaster did not just pass after an acute stress response but instead became rather persistent.

Along with negative responses to the disaster in the form of PTSD symptoms, the present study also found positive outcomes in the form of posttraumatic growth. This is in line with previous research which found that positive outcomes from a national disaster also formed at a collective level [29], confirming that indirect trauma through the media like direct trauma can also develop PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth.

Even though this study found that both PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth can be induced by indirect trauma, but the mechanism is still unclear as to how and why indirect trauma brings about posttraumatic growth. Linley Joseph [27] claimed that, because posttraumatic growth is reported for various traumatic events regardless of the type of trauma, what is important for posttraumatic growth is not the type of trauma but rather the subjective experience of the event. This implies that one does not really have to experience the traumatic event directly before one develops PTSD symptoms or posttraumatic growth. What is more important is the person’s perception and interpretation of the event. Wayment [41] revealed that individuals far removed from a traumatic event may still experience disaster-focused emotions, such as grief and survivor guilt, when they identify with the individuals who were directly affected by the trauma. This ‘perceived similarity to the victims’ also pinpoints the importance of subjective experience of traumatic events for developing PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth.

However, it is still not clear why some people perceive similarity to victims more easily than others and are more sensitive and responsive to another’s trauma. One potential variable is the openness of the mind. Lee [42] defined a healthy mind as an open system which actively accepts external stimuli and then adaptively changes in response to them, claiming that life being an open system [43] is a prerequisite for adaptation and evolution to a changing environment. Therefore, the individuals who are affected more by another’s trauma might have a healthier mind from an evolutionary point of view, because it is more open and responsive to the changes of their surroundings. Further research is needed to explore the role of the openness of the mind in both PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth.

Over the past two decades, mixed findings on the relationship between trauma and growth have emerged, but in the meta-analysis of those studies, PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth have shown a positive correlation [44,45]. Some studies even revealed that PTSD symptoms predicted posttraumatic growth [24,46]. Meanwhile, other studies found a curvilinear relationship between PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth [38,46-48]. Since most of these studies were conducted upon a directly traumatized sample, these findings should be carefully applied and generalized to indirect trauma.

Within the sample of this study, a linear trend was indicated between the severity of PTSD symptoms and the level of posttraumatic growth. Generally, these findings supported the hypothesis that the high severity of PTSD symptoms following indirect trauma through the media is associated with the high posttraumatic growth level. Even after excluding those who had pre-exiting PTSD symptoms, a similar linear trend was replicated within the rest of the sampled participants and extended to the previous findings, showing the general linear trend between PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth in the general public when exposed to trauma through the media.

These findings are consistent with what was found in the prior study which was conducted with similar methodology on direct and indirect trauma among adolescents and adults [49]. They found that resilience, defined as resistance to PTSD following adversity [50], and growth are inversely related even though both are salutogenic constructs. Then why do people with less symptoms show less growth? Magruder et al. [51] have made an interesting point about this question. They claimed that more resilient people, because they are better at dealing with adversity, do not develop PTSD, but for the same reason, they may not experience posttraumatic growth as their perception of the event does not reach the critical level of “seismicity.”

Despite the general linear trend between PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth, different details were found at a subscale level. Religious growth showed bigger p-values than other factors in the inter-group comparisons. Moreover, religious growth indicated a weaker correlation to posttraumatic growth (r=0.107, p<0.01) while mature thinking indicated an even stronger correlation (r=0.277, p<0.001) than the total score of K-SRGS-R (r=0.255, p<0.001). In addition, the reliability of the overall scale did not lower even after the items corresponding to religious growth (“I developed/increased my faith in God.”, “I developed/increased my trust in God.”, and “I understand better how God allows things to happen.”) were removed. In fact, in the original study of developing Stress-related Growth Scale, the items corresponding to religious growth are all omitted in the 15-item Stress-related Growth Scale-Short Form which consisted of one general factor about growth [24]. The present study also showed more significant results when data were analyzed excluding the items from religious growth. This suggests that the items from religious growth do not represent posttraumatic growth well while the items from mature thinking represent it even better than the total score of K-SRGS-R.

Epidemiological researches on PTSD showed that trauma is not something that only an unfortunate few go through, but something anyone can experience in the course of their life [52-58]. Moreover, if you include indirect trauma, it is almost impossible to avoid a traumatic experience while living. Many psychological theories which give explanations on the process of posttraumatic growth asserted the inevitability of going through a painful process to get to the point of growth, such as the model of re-schematization [59], the model of restoring shattered assumptions [60], and five stages of grief [61]. Therefore, the perception on trauma as a pathogenic factor needs to expand to also include trauma as a chance for growth. This expanded definition will help us on how to deal and live with trauma instead of trying to figure out how to avoid and prevent it.

The above findings should be considered with the study’s limitations in mind, and the future direction of the research is as follows.

First, the data of this study was collected using self-report questionnaires only. Self-report questionnaires are easy to conduct and score, but they have the limitations of not being able to measure individual’s unique responses to indirect trauma. In addition, it is difficult to assure whether the respondents answered in a sincere manner. Even though a large number of questionnaires were collected in this study, there were missing data due to some participants not responding to every question.

Second, the age of the participants in this study ranged from teens to 60 s, but the 20 s were most represented with 41.8%. It is a limit from the sampling method of this study which is the convenience sampling by the researchers. Therefore, the results of the study should be carefully interpreted when generalized to the whole population.

Third, despite a positive correlation between the severity of PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth level following indirect trauma through the media, there are no specific explanatory models of how indirect trauma transforms into growth. Further research is needed to better understand why some suffer persistent PTSD symptoms while others may experience growth from trauma, what factors affect the relationship between PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth, and the long term process of how PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth change over time.

Despite these limitations, this research is one of a few focused on both PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth from experiencing a national disaster through the media. The findings here have widened the perspective of indirect trauma by analyzing its positive as well as the negative effects and by examining empirically the relationship between PTSD symptoms and posttraumatic growth following indirect exposure to trauma. The current study will be the basis to elucidate further similar mechanisms of both direct trauma and indirect trauma.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2013S1A3A2043448).