White Matter Tract-Cognitive Relationships in Children with High-Functioning Autism Spectrum Disorder

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of the present study was to clarify the relationship between white matter tracts and cognitive symptoms in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

Methods

We examined the cognitive functions of 17 children with high-functioning ASD and 18 typically developing (TD) controls and performed diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tractography. We compared the results between the groups and investigated the correlations between the cognitive scores and DTI parameters within each group.

Results

The Comprehension scores in the ASD group exhibited a positive correlation with mean diffusivity (MD) in the forceps minor (F minor). In the TD group, the Comprehension scores were positively correlated with fractional anisotropy (FA) in the right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFO) and left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), and negatively correlated with MD in the left ATR, radial diffusivity (RD) in the right IFO, and RD in the left ATR. Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between the Matching Numbers scores and MD in the left uncinate fasciculus and F minor, and RD in the F minor. Furthermore, the Sentence Questions scores exhibited a positive correlation with RD in the right inferior longitudinal fasciculus. Relative to TD controls, the specific tract showing a strong correlation with the cognitive scores was reduced in the ASD group.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that white matter tracts connecting specific brain areas may exhibit a weaker relationship with cognitive functions in children with ASD, resulting in less efficient cognitive pathways than those observed in TD children.

INTRODUCTION

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in social interaction, repetitive behavior, and communication difficulties [1]. Worldwide, the prevalence of ASD is approximately 1.0% [2]. Several studies have identified impairments in various cognitive functions in individuals with ASD, including language comprehension [3], planning [4-6], and working memory [7]. These cognitive difficulties have been reported in individuals with high-functioning ASD as well as in those with low-functioning ASD.

Children with high-functioning ASD exhibit specific profiles when assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC)—the most commonly used battery for the assessment of intelligence [8]. Many children with high-functioning ASD exhibit strength on the Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI), attaining relatively higher scores on Matrix Reasoning than on other components, and weakness on the Working Memory Index (WMI) and Processing Speed Index (PSI), attaining relatively lower scores on Coding. Although their scores on the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI) usually match those of typically developing (TD) children, children with high-functioning ASD tend to exhibit high Similarities sub-scores and low Comprehension sub-scores [9-11]. In a previous study, correlation analyses revealed that low scores on Coding and Comprehension were correlated with poor communication ability and reciprocal social interaction, as assessed using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) [10]. In contrast, higher scores on the VCI and WMI were correlated with higher scores on the Adaptive Communication Abilities portion of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales [10]. These findings suggest that the cognitive impairments identified using the WISC are associated with behavior and influence the daily life among individuals with ASD.

The Das-Naglieri Cognitive Assessment System (DN-CAS) is designed to assess four cognitive processes, namely Planning, Attention, Simultaneous, and Successive (PASS) [12,13]. This battery is used to support the diagnosis and classification of various neurological conditions (i.e., learning disabilities, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, cognitive disabilities, giftedness, traumatic brain injury, serious emotional disturbance). The DN-CAS tests for personal strengths and weaknesses, evaluates the age-appropriateness of cognitive abilities, and predicts achievement [14]. In particular, the Planning score is useful for assessing executive function, which cannot adequately be assessed using the WISC alone [15]. According to one previous study that utilized the DN-CAS, individuals with ASD tend to score low on the Planning portion of the test [16].

Recent advancements in neuroimaging techniques have enabled the assessment of fine brain structures using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) is among the most useful techniques, as this method can be used to visualize anatomical connections between different brain regions and to quantify the microstructural integrity of specific white matter tracts [17-19]. The four main parameters for DTI are fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD). FA represents an overall measure of white matter microstructural integrity and is sensitive to myelination, axon diameter, fiber density, and fiber coherence [20-23]. MD measures overall randomized water motion and is sensitive to alteration of brain tissues [24,25]. AD measures axonal integrity and is sensitive to axonal damage [26]. RD measures myelin integrity, is susceptible to de- or dysmyelination, and is also affected by changes in axonal diameter or density [22,26-28].

The two most frequently used methods for analyzing DTI data include the region-of-interest (ROI) method [29,30] and Tract-Based Spatial Statistics [31]. However, previous DTI studies utilizing these methods have yielded incongruent results. Such studies have reported that FA values for individuals with ASD were both lower and higher than those of controls—and that RD values were higher than those of controls—in the following white matter tracts: superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFO), uncinate fasciculus (UNC), anterior thalamic radiation (ATR), corpus callosum (CC), forceps minor (F minor), and forceps major (F major) [32-37]. These tracts are significantly associated with various aspects of cognition in healthy individuals; for example, SLF is associated with language and processing speed [38,39], ILF with auditory comprehension [40], IFO with semantic memory and processing speed [38,41], UNC with auditory-verbal memory [42], ATR with executive function and working memory [38,43], F minor with working memory and executive function [43,44], and F major with visuospatial cognition [45].

In addition, several studies have investigated the correlation between white matter abnormalities and the severity of ASD. Alexander et al. [46] reported that FA in the CC exhibited a positive correlation with Processing Speed on the WISC in individuals with ASD. Subsequent studies revealed that FA in the right ATR and right UNC exhibited a negative correlation with the total score on the Social Responsiveness Scale [32]. FA in the bilateral ILF, right IFO, and F major exhibited a negative correlation with the social score on the ADOS, while FA in the right ILF and right IFO exhibited a negative correlation with the social score on the Autism Diagnostic Interview, Revised (ADI-R) [34]. FA in the bilateral IFO and F major exhibited a negative correlation with the communication score on the ADOS [34,47], while FA in the left SLF and left IFO exhibited a negative correlation with the communication score on the ADI-R [34].

Collectively, these findings suggest that individuals with ASD exhibit structural abnormalities in the white matter tracts of the brain and that these abnormalities are associated with the severity of autism and cognitive deficits. However, in these previous studies, the age of included individuals varied widely, ranging from childhood to adulthood. Especially during childhood, myelination of axons in the human brain plays an important role in the maturation of cognitive functions [48]. According to the developmental trajectory, the time sequence of myelin maturation differs from area to area, and slow-maturing frontal tracts such as the IFO, orbitofrontal callosum, and cingulum exhibit peak levels of myelination during the thirties [49]. However, only one previous study focused on schoolaged children with ASD when examining the correlation between microstructural abnormalities and behaviors, as assessed using the WISC, Social Communication Questionnaire, and Sensory Profile [35]. Furthermore, few research groups have investigated and compared the detailed correlations between subtest scores on the WISC or DN-CAS and white matter tracts in children with ASD and their TD counterparts.

Therefore, in the present study, we focused on children in late childhood and early adolescence, who were still in the immature stages of myelin development. Our aim was to investigate the relationship between cognitive functions and the microstructural integrity of white matter tracts in children with ASD. We hypothesized that white matter characteristics would be related to cognitive impairments in children with ASD.

To achieve our aim, we first examined differences in cognitive functions between children with ASD and age-, sex-, handedness-, and IQ-matched TD controls using the WISC-IV and DN-CAS. Second, using the ROI method, we performed DTI tractography to extract key white matter tracts for cognition and compared their parameters between the groups. Third, we investigated the correlations between cognitive functions and DTI parameters within each group.

METHODS

Participants

Seventeen boys with ASD (mean age: 12.0±1.5 years; range: 9–14 years) and 18 TD boys (mean age: 11.9±1.6 years; range: 9–14 years) participated in the present study. Participants with ASD and TD controls were matched according to age and Full-Scale Intelligence Quotient (FSIQ: Table 1). All were confirmed to be right-handed using the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory [50]. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (12168-9).

Children with ASD

Children with ASD were recruited from the Pediatric Department of our hospital and diagnosed by expert pediatric neurologists based on criteria detailed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [1]. Diagnoses were further confirmed using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G) [51]. Children with ASD who had a history of seizures, head injury, and those with genetic disorders were excluded. Two children with ASD were undergoing treatment with methylphenidate at the time of the study.

TD children

TD children were recruited as volunteers through advertisements in neighboring cities. TD children had no history of neurological, psychiatric, or developmental disorders and had not received special education support. They were also confirmed to have no ASD traits using the Japanese version of the Autistic Screening Questionnaire [52,53].

Intelligence quotient and cognitive abilities assessment

Intelligence Quotient (IQ) was assessed using the WISC-Fourth Edition (WISC-IV). In the present study, to ensure average intelligence and minimize the effects of IQ on cognitive assessment, we selected participants with an FSIQ >85.

The WISC-IV comprises 10 core and five supplemental subtests designed to assess intellectual abilities based on the following four main cognitive indices: VCI, PRI, WMI, and PSI. The VCI includes the following five subsets: Similarities, Vocabulary, Comprehension, Information, and Word Reasoning. The PRI includes Block Design, Picture Concepts, Matrix Reasoning, and Picture Completion. The WMI includes Digit Span, Letter-Number Sequencing, and Arithmetic. The PSI includes Coding, Symbol Search, and Cancellation. All index scores have an average of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. All subtest scores have an average of 10 and a standard deviation of 3. Higher scores on this assessment battery are associated with better cognitive functioning [54,55].

The DN-CAS comprises 12 subtests designed to assess cognitive processes including PASS [13,56]. Planning includes Matching Numbers, Planned Code, and Planned Connections. Attention includes Expressive Attention, Number Detection, and Receptive Attention. Simultaneous includes Nonverbal Matrices, Verbal-Spatial Relations, and Figure Memory. Successive includes Word Series, Sentence Repetition, and Sentence Questions. All PASS scale scores have an average of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. All subtest scores have an average of 10 and a standard deviation of 3 [13,56]. Higher scores on this assessment battery are associated with better cognitive processing skills.

MRI data acquisition

All images were acquired using a 3.0-Tesla MR system (Discovery MR750w; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). DTI data were acquired using a single-shot spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequence with sensitivity-encoding parallel imaging (factor of two). Diffusion-weighted images were acquired in the axial plane with 25 non-collinear directions. The imaging parameters were as follows: repetition time (TR)=12,000 ms; echo time (TE)=74.3 ms; field-of-view=260×260 mm2; matrix size=128×128; slice thickness=3 mm; slice gap=0; number of slices=50; number of excitations=1; and diffusion-weight factor b=1000 and 0 s/mm2. Foam pillows and cushions were used to minimize the head motion of participants.

DTI data analysis

Preprocessing

Preprocessing of the DTI data was performed using ExploreDTI (www.exploredti.com). The motion artifacts and eddy current-induced geometric distortions were corrected, and the B-matrix was reoriented to provide the appropriate orientational information [57]. To detect group differences in head movement, the three translation and rotation parameters for each participant were extracted using ExploreDTI, and statistical analysis was performed. There were no significant differences in head motion between the two groups (translation X: p=0.84, translation Y: p=0.96, translation Z: p=0.55, rotation X: p=0.72, rotation Y: p=0.58, rotation Z: p=0.88).

Tractography approach

Tensor calculations and tractography were performed using ExploreDTI. The built-in whole-brain tractography tool of ExploreDTI was employed for all data using a deterministic streamline approach, which was based on previously developed tractography algorithms [57-59]. The deterministic streamline tractography parameters were as follows: seed point resolution=2.0 mm, 2.0 mm, 3.0 mm; seed FA threshold=0.2; and angle threshold=30°. A multi-ROI approach [29] was used to reconstruct all tracts of interest. For this multi-ROI approach, we used the “OR/SEED,” “AND,” and “NOT” operations to select the fiber tracts of interest [60].

Reconstructed tracts and DTI outcome measurements

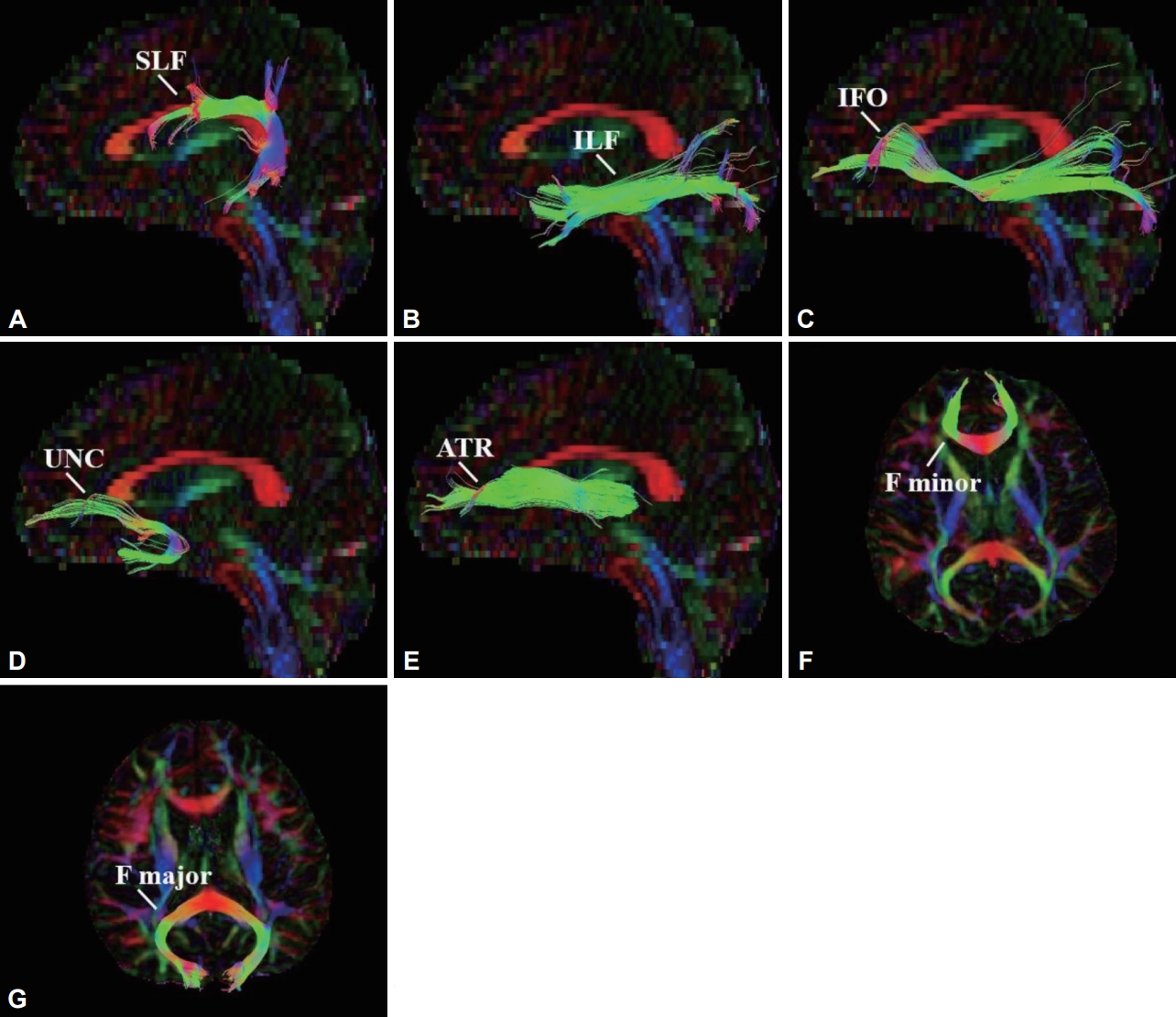

Seven white matter tracts were selected for tractography, including the SLF, ILF, IFO, UNC, ATR, F minor, and F major. These tracts were reconstructed in accordance with protocols described in previous publications [60,61]. We then analyzed the FA, MD, AD, and RD value of each tract. Figure 1 depicts a representation of the reconstructed tracts.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.0 [62]. Independent-samples t-tests were used to compare the mean values for age, WISC-IV scores, and DN-CAS scores between the two groups. The tractography results were also compared using independent-samples t-tests with group (ASD/TD) as the between-subjects factor. Within each group, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between the DTI outcome measurements and the WISC-IV or DN-CAS subtest scores for which significant differences were observed to evaluate the association between microstructural integrity and cognitive function. When determining statistical significance, Bonferroni correction was performed for multiple comparisons (p=0.004).

RESULTS

Between-group differences in WISC-IV and DN-CAS scores

There were no significant differences in the WISC-IV index values between the two groups. However, the ASD group exhibited significantly lower scores than did TD controls on the following WISC-IV subscales: Comprehension (p=0.048), Coding (p=0.041), and Cancellation (p=0.003) (Table 2). Although there were no significant differences in the total DNCAS scores, the ASD group exhibited significantly poorer performance than did the TD group on the Planning (p=0.011) portion of the DN-CAS and on the Matching Numbers (p=0.027) and Sentence Questions (p=0.003) subtests (Table 3).

Between-group differences in DTI measurements

In the ASD group, the FA value of F major was lower (p=0.049) than that in the TD group. However, there were no significant differences in the MD, AD, or RD values of any white matter tracts examined (Table 4).

Correlations between the DTI measurements and WISC-IV and DN-CAS subtests

We investigated the correlations between the DTI measurements and the subtest scores on the WISC-IV and DN-CAS. Within the TD group, the Comprehension scores on the WISC-IV were positively correlated with FA in the right IFO (r=0.71, p=0.0009) and left ATR (r=0.67, p=0.002), and negatively correlated with MD in the left ATR (r=-0.75, p=0.0003), RD in the right IFO (r=-0.66, p=0.003), and RD in the left ATR (r=-0.80, p=0.0001) (Table 5, Figure 2A-C, E, and F). In addition, participants’ scores on the Matching Numbers subsection of the DN-CAS exhibited a significant positive correlation with MD in the left UNC (r=0.65, p=0.004) and F minor (r=0.67, r=0.003), and with RD in the F minor (r=0.74, p=0.0004). Furthermore, a positive correlation was observed between the scores on the Sentence Questions subsection of the DN-CAS and RD in the right ILF (r=0.65, p=0.004). These results remained significant after applying Bonferroni correction (Table 6, Figure 2G-J).

Correlations between the comprehension, coding, and cancellation scores on the WISC-IV and the FA, MD, AD, and RD of white matter tracts

Scatter plots of the correlation analyses in the autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and typically developing (TD) groups. Scores on the Comprehension section of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) are (A) positively correlated with fractional anisotropy (FA) values in the right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFO) in the TD group (r=0.71, p=0.0009), but not in the ASD group (r=-0.37, p=0.141); (B) positively correlated with FA values in the left anterior thalamic radiation (ATR) in the TD group (r=0.67, p=0.002), but not in the ASD group (r=-0.51, p=0.037); (C) negatively correlated with mean diffusivity (MD) values in the left ATR in the TD group (r=-0.75, p=0.0003), but not in the ASD group (r=0.41, p=0.106); (D) positively correlated with MD values in the forceps minor (F minor) in the ASD group (r=0.68, p=0.003), but not in the TD group (r=0.43, p=0.079); (E) negatively correlated with radial diffusivity (RD) values in the right IFO in the TD group (r=-0.66, p=0.003), but not in the ASD group (r=0.17, p=0.530); and (F) negatively correlated with RD values in the left ATR in the TD group (r=-0.80, p=0.0001), but not in the ASD group (r=0.52, p=0.033). Scores on the Matching Numbers portion of the Das-Naglieri Cognitive Assessment System (DN-CAS) are (G) positively correlated with MD values in the left uncinate fasciculus (UNC) in the TD group (r=0.65, p=0.004), but not in the ASD group (r=0.15, p=0.572); (H) positively correlated with MD values in the F minor in the TD group (r=0.67, p=0.003), but not in the ASD group (r=-0.03, p=0.923); and (I) positively correlated with RD values in the F minor in the TD group (r=0.74, p=0.0004), but not in the ASD group (r=0.01, p=0.973). Scores on the Sentence Questions portion of the DN-CAS are (J) positively correlated with RD in the right inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF) in the TD group (r=0.65, p=0.004), but not in the ASD group (r=0.02, p=0.934). *p<0.05 (significance level), **p<0.004 (significance level following Bonferroni correction).

Correlations between the matching numbers and sentence questions scores on the DN-CAS and the FA, MD, AD, and RD values of white matter tracts

Within the ASD group, only a positive correlation between the Comprehension scores on the WISC-IV and MD in F minor remained significant after Bonferroni correction (r=0.68, p=0.003) (Table 5, Figure 2D). No other significant correlations between the DTI measurements and participants’ scores on any subtests were observed. In the ASD group, non-significant correlations were observed between the Comprehension scores on the WISC-IV and FA in the right IFO and left ATR, between the Comprehension scores and MD in the left ATR, and between the Comprehension scores and RD in the right IFO and left ATR. Non-significant correlations were also observed between the Matching Numbers scores on the DN-CAS and MD in the left UNC and F minor, between the Matching Numbers scores and RD in the F minor, and between the Sentence Questions scores on the DN-CAS and RD in the right ILF in the ASD group. In the TD group, the Comprehension scores on the WISC-IV were non-significantly correlated with MD in the F minor (Table 5 and 6).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found 1) characteristic cognitive weakness, 2) reduced FA value in the F major, and 3) no specific differentiation for cognitive function associated with the specific tract in children with ASD. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the relationships between cognitionrelated white matter tracts and cognitive function in children with ASD using the DN-CAS and DTI tractography.

Participants in the ASD group scored poorly on the Comprehension, Coding, and Cancellation subtests of the WISC-IV when compared with TD controls, consistent with the findings of previous studies [9,10]. Furthermore, on the DN-CAS, the ASD group exhibited significant weakness on the Matching Numbers and Sentence Questions subtests when compared with the TD group. The Matching Numbers section assesses planning, processing speed, and working memory, while the Sentence Questions section assesses verbal comprehension and syntax [13,15]. Many children with ASD exhibit impairments in language comprehension, planning, and processing speed [6,10,63]. Therefore, these findings indicate that the DN-CAS appropriately reveals the cognitive impairments of children with high-functioning ASD.

Differences in DTI measurements between the ASD and TD groups

In the present study, the FA values in the F major were significantly lower in the ASD group than in the TD group, consistent with the findings of a previous study [33]. The F major is a commissural fiber tract that consists of the splenium of the corpus callosum and connects the occipital lobes [61,64]. The F major plays roles in visuospatial cognition [45], processing speed [65], memory and executive function [66], and vocabulary and semantic processing [45,67]. Previous studies have indicated that children with ASD exhibit impairments in processing speed, planning, and language comprehension [6,10,63], suggesting that alterations to the F major may play a role in these ASD-related impairments.

Correlations between DTI measurements and cognitive function

Our findings indicated that, in the ASD group, the Comprehension scores on the WISC-IV exhibited a positive correlation with MD in the F minor. Previous studies have revealed that the F minor plays a role in syntactic performance [68]. In one functional MRI study, activation of the left inferior frontal gyrus, including the pars orbitofrontal area, was lower in the ASD group than in the TD group during a sentence comprehension task [69]. Thus, our findings support the notion that the F minor plays a key role in comprehension, as assessed using the WISC-IV, among individuals with ASD.

Other than the aforementioned correlation, no correlations were observed between the subtest scores and DTI outcome measurements in the ASD group. In contrast, nine correlations between DTI measurements and the subtest scores on the WISC-IV and DN-CAS were observed in the TD group. It is known that the maturation of white matter tracts that connect restricted regions is closely associated with cognitive development in those particular regions [48]. Therefore, our findings suggest that, in children with ASD, specific brain areas exhibit a weaker relationship with specific cognitive functions than they do in TD controls, resulting in less efficient cognitive pathways. Indeed, several functional MRI studies have demonstrated that the brains of individuals with ASD exhibit broader activation during various tasks [70,71]. Although white matter maturation supports the development of cognitive function in TD children [48], this effect is delayed in children with ASD [72]. However, recent studies have revealed that adaptive myelination may occur, depending on the neuronal activity. Eigsti et al. [73] reported that early intervention and experience may normalize behavioral language performance and that individuals with an optimal ASD outcome exhibit plasticity within the neural circuits associated with language.

More precisely, structural changes to white matter during childhood reflect the interplay among cell proliferation and apoptosis, dendritic branching and pruning, and synaptic formation and elimination. Therefore, such changes are influenced by the strength of proper neural connections and the pruning of inefficient pathways [74]. However, further studies are required to determine whether early intervention during the critical period can alter the myelination trajectory of young children with ASD and whether such alterations can influence the acquisition of cognitive skills in the future.

The present study possesses several limitations of note. First, the sample was small and included only boys. Howe et al. [75] reported that boys and girls with ASD exhibit differences in their cognitive abilities. Although the present study focused on boys alone, further studies focusing on the association between white matter tracts and cognition in girls with ASD are required. Second, to exclude the effects of age, sex, and IQ, we focused on children with high-functioning ASD. Therefore, our findings may not be applicable to children with low-functioning ASD. To determine whether our findings can be generalized to all individuals with ASD, a larger sample size including individuals with a broader range of IQs is required. Third, in the correlation analysis, our results for MD and RD were inconsistent. Although MD and RD decrease with development, we could not analyze longitudinal changes in cognitive functions and white matter microstructure due to the narrow age range of the participants.

In conclusion, the results of the present study demonstrate that children with ASD and TD controls exhibit significant differences in cognitive functions such as language comprehension, processing speed, and planning, and in the white matter microstructure of the F major. Moreover, although many correlations were observed between DTI measurements and subscale scores in the TD group, only one correlation was observed in the ASD group. Thus, our findings suggest that, in individuals with ASD, processing skills depend on a widespread neural network that is less directly associated with specific tract measurements, and that the specific brain areas affected are less efficiently engaged in their respective cognitive pathways. In addition, our findings may aid in clarifying the mechanisms underlying cognitive dysfunction in children with ASD and provide evidence in support of early intervention for their cognitive and social development.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant numbers 15K09619 and 15H01581 and the Program for Promoting the Enhancement of Research Universities by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. We wish to thank all the children and their parents for their participation in this study.