|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 16(7); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Little is known about the treatment of gender dysphoria among children and adolescents in Japan. This preliminary survey aims to improve understanding of current clinical practice for treatment of children with gender dysphoria. Subjects were 315 certified child and adolescent psychiatrists in Japan. The questionnaire asked about clinical experiences concerning gender dysphoria and gender identityrelated concerns. A total of 128 psychiatrists responded to the questionnaire. Mean length of clinical experience was 24.2±10.0 years in total and 16.9±11.5 years as child and adolescent psychiatry specialists. Among the respondents, 74 (57.8%) had seen children and adolescents with DSM-5 gender dysphoria, and 87 (67.7%) had examined cases with gender identity-related concerns. The mean number of experienced cases with gender dysphoria was 1.80±2.3 per respondent. We found that even among certified child and adolescent psychiatrists in Japan, experience with treatment of children with gender dysphoria was limited.

Increasing attention has been paid to sexual minorities over the past decade in Japan. A large-scale survey in 2015 estimated the total number of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals in Japan was approximately 9.7 million [1,2]. But less is known about Japanese youth who identify as LGBT, and in particular those who identify as transgender, an umbrella term that describes individuals whose gender identity, expression, or behavior differs from that which was assigned at birth. A survey of LGBT persons among Japanese university students found prevalence rates of 2.7%, 0.5%, 5.3%, and 0.8%, respectively [3]. One study among high school students in New Zealand, found that 1.2% of them reported being transgender [4]. From these findings, one might presume that a considerable number of high school and university students in Japan self-identify as transgender.

In 2015, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan declared a need for schoolbased interventions for students with gender dysphoria [5]. Prior to this announcement, a national survey of schools by the MEXT in 2013 revealed that at least 606 students in primary, junior-high and high school were aware of their gender incongruence, and about 60% of them received some form of special treatment at school [6]. Examples of such measures for those with gender incongruence included special accommodations for toilets (41.4%), changing-rooms (35.3%), school uniforms (31.3%), bed assignments during field trips (27.9%), and swimming classes (20.7%).

Because gender related distress can cause excessive psychological burden on the very young [7], child and adolescent psychiatrists need to pay more attention to the mental health of students with gender dysphoria. However, little is known about current approaches to addressing gender dysphoria in Japanese youth.

The aim of this survey was to better understand the current state of clinical practice for school-age children with gender dysphoria and gender identity-related concerns and to demarcate areas where further support may be needed.

The subjects of this study were certified child and adolescent psychiatrists. The certification system of child and adolescent psychiatry specialists in Japan by the Japanese Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (JSCAP) has been discussed elsewhere [8,9]. We mailed a survey to all certified child and adolescent psychiatrists on a list provided by the JSCAP office on December 1, 2015 (315 total).

The questionnaire asked about clinical experiences-including the number of cases seen, the specific content of complaints, interventions chosen, and challenges encountered within the realm of gender dysphoria and gender identity-related concerns.

The questionnaire consisted of twenty questions divided into six categories: 1) demographic information; 2) collaboration with specialized gender identity clinics; 3) clinical experience of cases with gender dysphoria of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-5; 4) clinical experience with cases of gender identity-related concerns; 5) free description about clinical practice regarding gender related matters; and 6) free description about expected future attitudes within their profession toward gender dysphoria. The questionnaire took approximately 15 minutes to complete. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Kawasaki City Center for Children and Family Services (KKC-H27-1002).

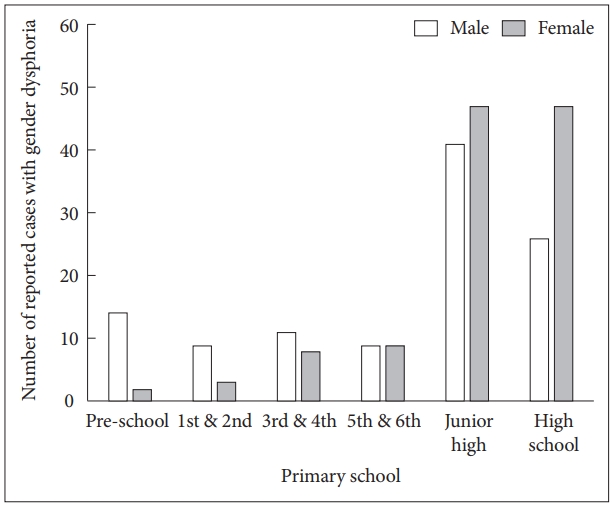

The total number of respondents was 128 (response rate 40.6%). The mean (±SD) length of clinical experience was 24.2±10.0 years in total and 16.9±11.5 years as child and adolescent psychiatry specialists. Only 2 respondents (1.6%) worked at medical institutes with specialized gender identity clinics while 31 respondents (24.2%) were collaborating with gender identity clinics at other institutes. Among the 128 respondents, 74 (57.8%) had seen children and adolescents with DSM-5 gender dysphoria, and 87 (67.7%) had examined cases with gender identity-related concerns. The mean number of career-span experience with cases of gender dysphoria was 1.80±2.3 per respondent. The median number of experienced cases was 1. The rate of referred cases by school level was as follows: preschool 7.1%, primary school 21.7%, junior high school 38.9%, and high school students 32.3% (Figure 1). Regarding the assigned gender of referrals, male cases were dominant, whereas after the mid-primary school years, females were referred more frequently than males.

With respect to the attitudes about clinical practice in this field, 52 clinicians (40.6%) stated they hope to continue working in this area by collaborating with specialized gender identity clinics, while 24 (18.8%) said they prefer to refer cases of gender dysphoria to specialists due to the inherent difficulties with diagnosis and intervention.

Optional freely written respondent comments highlighted the challenge of differential diagnosis in the context of autism spectrum disorder, child abuse and dissociative disorders, as well as difficulties in diagnosis and intervention. Several respondents emphasized that mental health professionals should provide children and their families with information based on current evidence. Others noted the importance of accepting at face value the responses from the children themselves. It was also noted that cases should be followed for a sufficient period of time without making a definitive diagnosis purposely to allow a more definitive understanding of patient’s situation. In addition, some respondents stressed that as professionals we should take their gender nonconforming behaviors as they are, and be aware of the great fluidity and expanse of gender incongruence, without imposing a binary view of gender. Most of the respondents understood that gender dysphoria in childhood was not synonymous with a progressing diversity in gender expression and would not inevitably continue into adulthood. Many respondents described their diagnostic uncertainty and possible mislabeling, and expressed a wish to have standardized clinical guidelines established for child and adolescent cases with suspected gender dysphoria.

To the best of our knowledge, our survey is the first to investigate clinical practices of child and adolescent psychiatrists who may have treated school-age children with gender dysphoria and gender identity-related concerns in Japan. Even among experienced and certified child and adolescent psychiatrists in Japan, the experience with diagnosis and intervention of students with gender dysphoria is limited. There was diversity in attitudes about best approaches to the management of gender dysphoria and gender identity-related concerns. The results suggest that respondents should try their best to support children and adolescents with gender identity-related concerns and manage treatment carefully through trial-and-error.

According to the report by the GID Clinic of Sapporo Medical University Hospital (SMUH), the estimated prevalence of male-to-female (MTF) and female-to-male (FTM) individuals is 3.97 and 8.20 per 100,000 people respectively in Japan [10]. Among 643 cases with confirmed diagnosis of GID in the GID Clinic of SMUH from December 2003 to March 2018, 62 cases (9.6%) visited the clinic before they graduated high school or its equivalent. Of these 62 cases, 46 of them were diagnosed as FTM-GID (10.8% of all FTM-GID cases, mean age 16.0±1.9 years) and 16 cases were MTF-GID (7.4% of all age MTF-GID, mean age 17.1±0.8 years). Thus, there may be a need for child and adolescent psychiatrists to provide expertise in the treatment of GID in this group.

In Japan, there is only one academic society for gender dysphoria and gender identity-related concerns: the Japanese Society of Gender Identity Disorder (JSGID) (www.gid-soc.org). JSGID has its own certification system. However, as of December 2018, the number of GID specialists are only 20 including psychiatrists, urologists, gynecologists and plastic surgeons. The GID committee of the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology (JSPN) published the fourth version of “the Guideline of Diagnosis and Treatment for Gender Identity Disorder” in 2012 [11]. This guideline follows the Standard of Care outlined by The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) [12]. In the latest version of these guidelines, more attention has been paid to adolescents. However, interventions listed in the guidelines are mainly hormonal and physical treatments delivered at specialized gender clinics. To give clinicians the necessary knowledge and guidance towards proper treatment of this population, especially for psychological interventions, practical guidelines for gender identity-related concerns in school-age children are needed.

This study has several limitations. The response rate is low, and thus the sample size was limited. Because of the relatively small number of child and adolescent psychiatrists in Japan 8 and the interest in their practice, one possible reason for the low response rate might be that the recipients of the survey may have been overwhelmed with both clinical work and requests to participate in other surveys. We could not provide background characteristics of responders versus non-responders. There might be a significant bias in our findings because child and adolescent psychiatrists with some gender dysphoria experience may be more likely to respond to the questionnaire than those without.

Our survey was the first to investigate the clinical practices of child and adolescent psychiatrists who may have treated school-age children with gender identity-related concerns in Japan. Even among experienced child and adolescent psychiatrists, the experience with diagnosis and interventions for students with gender dysphoria is limited. Our results suggest that Japanese child and adolescent psychiatrists are awaiting clinical guidelines including appropriate psychological interventions to support school-age cases with gender related issues effectively.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all of the subjects for completing the questionnaire. This work was partially supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on The Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (Syogaisya-Taisaku-Sogo-Kenkyu-Kaihatsu-Jigyo to M.T.; JP19dk0307073h).

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Masaru Tateno, Chiho Ueno and Hiroshi Nakayama contributed equally to Conceptualization, Methodology, Data collection and Formal analysis of data. Chiho Ueno drafted initial manuscript followed by Writing final manuscript, Reviewing and Editing by Masaru Tateno and Tae Woo Park equally.

REFERENCES

1. Statistics Bureau of Japan. Results of a National Census in 2015. Tokyo: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications; 2016.

2. Dentsu Diversity Labo. Survey on Sexual Minority (in Japanese). Tokyo: Dentsu Inc; 2015.

3. Ikuta N, Koike Y, Aoyagi N, Matsuzaka A, Fuse-Nagase Y, Kogawa K, et al. Prevalence of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender among Japanese university students: a single institution survey. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2016;29.

4. Clark TC, Lucassen MF, Bullen P, Denny SJ, Fleming TM, Robinson EM, et al. The health and well-being of transgender high school students: results from the New Zealand adolescent health survey (Youth’ 12). J Adolesc Health 2014;55:93-99.

5. MEXT. A Manual for Discreet Support at School to Students with Gender Identity Disorder and Gender Related Issues (in Japanese). Tokyo: Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; 2015.

6. MEXT. Intervntion to students with gender variance (in Japanese). Tokyo: Japan Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; 2014.

7. Perez-Brumer A, Day JK, Russell ST, Hatzenbuehler ML. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among transgender youth in California: findings from a representative, population-based sample of high school students. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2017;56:739-746.

8. Tateno M, Uchida N, Kikuchi S, Kawada R, Kobayashi S, Nakano W, et al. The practice of child and adolescent psychiatry: a survey of earlycareer psychiatrists in Japan. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2009;3:30

9. Tateno M, Inagaki T, Saito T, Guerrero APS, Skokauskas N. Current challenges and future opportunities for child and adolescent psychiatry in Japan. Psychiatry Investig 2017;14:525-531.

10. Baba T, Endo T, Ikeda K, Shimizu A, Honnma H, Ikeda H, et al. Distinctive features of female-to-male transsexualism and prevalence of gender identity disorder in Japan. J Sex Med 2011;8:1686-1693.

11. Matsumoto Y, Abe T, Ikeda H, Oda H, Kou J, Sato T, et al. Guideline of diagnosis and treatment for gender identity disorder (in Japanese). Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi 2012;114:1250-1266.

12. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Version 7. East Dundee, Illinois: The World Professional Association for Transgender Health; 2011.