Clinical Data Interchange Standards in Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) proposed outcome measures for clinical trials on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the Therapeutic Area User Guide for AD (TAUG-AD). To investigate how well the clinical trials on AD registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov complied with the recommendations on outcome measures by the CDISC.

Methods

We compared the outcome measures proposed in the TAUG-AD version 2.0.1 with those employed in the protocols of clinical trials on AD registered in ClinicalTrials.gov.

Results

We analyzed 101 outcome measures from 305 protocols. The TAUG-AD listed ten scales for outcome measures of clinical trials on AD. The scales for cognition, activities of daily living, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, and global severity listed in TAUG-AD were most frequently employed in the clinical trials on AD. However, TAUG-AD did not include any scale on quality of life. Also, several scales such as Montreal Cognitive Assessment, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living, and Cohen- Mansfield Agitation Inventory not listed in the TAUG-AD were commonly employed in the clinical trials on AD and changed over time.

Conclusion

To properly standardize the data from clinical trials on AD, the gap between the TAUG-AD and the measures employed in real-world clinical trials should be filled.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that affects millions of people worldwide but is currently incurable. Although AD trials typically use continuous outcome measures to provide good statistical power and increasingly include biomarkers of AD pathologies to reduce heterogeneity, there have been about 150 failed attempts at developing AD drugs in the last two decades [1].

Data standards allow for proper integration of clinical data sets and represent the essential foundation for regulatory endorsement of drug development tools. Such tools increase the potential for success and accuracy of trial results [2]. Regulatory agencies of the United States (US) and the European Union recommended a core set of outcome measures for future disease-modifying trials on AD. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the US recommends that clinical trials relating to AD should use a coprimary outcome measure approach, in which efficacy is examined using both cognitive and functional or global assessment scales [3]. In Europe, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use recommends that two primary endpoints should be used to reflect the cognitive and functional domains and that global assessment should be included as a key secondary endpoint [4]. However, these recommendations did not specify the measures for each outcome domain, and previous clinical phase II/III trials for AD registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov did not follow these recommendations, making it difficult to compare and contrast results [5].

In the US, FDA mandated the use of the Study Data Tabulation Model (SDTM) for new drug applications since 2016. The SDTM is the primary standard from the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) that governs the structure of data collected from clinical studies and defines the variables and rules associated with specific observation classes including events, interventions, and findings [6]. The CDISC is an organization for developing global standards of data collection, sharing, and archiving of clinical researches [7,8] and structures formal data models for submissions to regulatory authorities [9]. The CDISC also develops the Therapeutic Area User Guide (TAUG) for specific diseases including AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to share common strategies in data standards for review, analysis of data, and submission to a regulatory agency [2,10]. The TAUG includes the most common research concept and disease assessments including scales and biomarkers that can be employed as outcome measures in clinical trials [2,10,11].

However, it has never been investigated how well the clinical trials on AD registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov complied with the recommendations on outcome measures by the CDISC. In this study, we compared the outcome measures between the clinical trials registered to ClinicalTrials.gov before and after the release of the TAUG for AD and MCI version 2.0.1 (TAUG-AD 2.0.1), and examined how well the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 was accepted in the clinical trials on AD.

METHODS

Study design

This study was undertaken as a cross-sectional analytic study on the accordance of the study methods of AD trials listed in ClinicalTrials.gov [12] with the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. The cross-sectional study is one of the descriptive studies to describe the distribution of variables [13]. This study was carried out on scales employed as a primary endpoint of clinical trials on AD; these scales resulted from protocols listed in ClinicalTrials.gov and TAUG-AD 2.0.1.

Data collection

The protocol search in ClinicalTrials.gov was conducted on November 19, 2018. ClinicalTrials.gov is a self-reporting comprehensive clinical trial registry system for all diseases [14,15]. The database was launched in 2000 based on the FDA Modernization Act of 1997 [16]. The number of trials registered in Clinical-Trials.gov has been rapidly increasing more than tenfold [17] since the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors required trial registration in a public clinical registry system in 2005 [18]. We searched the protocols of AD clinical trials on November 19, 2018, at ClinicalTrials.gov using the following search terms: Dementia; Alzheimer; Alzheimer Disease; Alzheimer Disease, Late Onset; Alzheimer Disease, Early Onset; Alzheimer’s Disease (Incl Subtypes); Alzheimer; Dementia, Mixed type (Etiology); Dementia Alzheimers; Dementia, Alzheimer Type; Dementia of Alzheimer Type; Dementia, Vascular; Dementia with Lewy Bodies; Dementia Frontal; Dementia, Mixed; Dementia, Mild; Dementia, HIV; Mild Cognitive Impairment; Cognitive dysfunction; Cognitive decline.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for protocols

We defined the study population as people with dementia (PWD) due to AD, people with MCI due to AD, and people with AD. We included protocols if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) at least one standardized outcome measure for diagnosis and to evaluate symptoms, severity, and other factors in people with AD and 2) an interventional study. We excluded studies that met the following criteria: 1) outcomes that were only qualitative, economic, related to drug level or caregivers, and biomarkers; 2) observational studies; and 3) phase 1 or 4 studies. We did not limit the study status, type of intervention, and funders of the trials. Two researchers independently selected the protocols, while the other researchers resolved any discrepancies between the two researchers.

TAUG-AD 2.0

The TAUG-AD 2.0.1, which was released on January 5, 2016, recommended two scales for cognitive function (Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale–Cognitive Subscale [ADAS-Cog] and Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] [19]), three scales for activities of daily living (ADLs) (Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study for Activities of Daily Living in Mild Cognitive Impairment [ADCS-ADL MCI] [20], Disability Assessment for Dementia [DAD] [21], and Functional Activities Questionnaire [FAQ] [22]), two scales for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) (Neuropsychiatric Inventory [NPI] [23] and Geriatric Depression Scale [GDS] [24]), two scales for global severity (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] [25] and Clinical Global Impression [CGI] [26]), and one for ischemic burden (Modified Hachinski Ischemic Scale [MHIS] [27]) in the chapter of disease assessments [28]. Compared to the CDISC TAUG-AD 1.0 released on September 9, 2011, the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 included 10 additional clinical scales applicable to AD and MCI. The TAUG-AD version 1.0 did not include any examples of imaging biomarkers and clinical scales relevant to AD and MCI.

Data analysis

We examined the frequency of use of each scale and the ratio of using each scale to measure such as cognition, ADL, and global severity domains. Two population proportion analysis was conducted to identify the change in utilization of the outcome measurements with the R version 3.5.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Characteristics of protocols

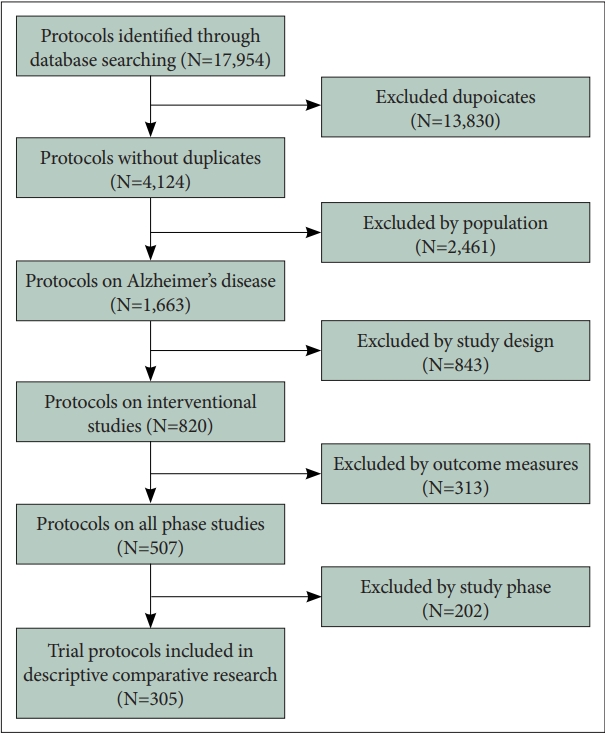

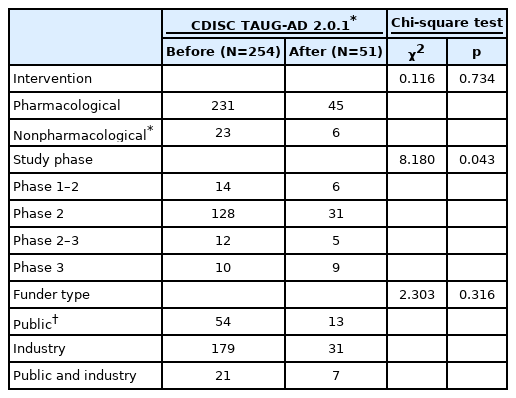

We identified 4,124 protocols and included 305 protocols in the current analysis after removing 3,819 protocols that did not meet the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Most of the clinical trials were pharmacological interventions (n=276, 90.5%) and one-fifth of their study protocols were registered after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 (n=51, 16.7%) (Table 1). We identified 101 outcome measures from the protocols: 45 for cognitive function, 18 for ADL, 18 for BPSD, 11 for global severity, and 9 for other outcome measures such as quality of life (QoL). The cognitive scales were most commonly employed as a primary endpoint before and after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 (p=0.889), followed by the global severity scales. After the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, the scales on ADL were no more employed while those on BPSD had become far more employed as the primary endpoint in AD trials (Table 2). The proportion of the clinical trials that employed a cognitive measure and a functional or global severity measure as coprimary endpoints were 70.1% before the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 while 56.9% after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1.

Characteristics of the protocols of clinical trials on Alzheimer’s disease registered in ClinicalTrials.gov

Cognition

To measure the cognitive function, 265 out of 305 protocols employed 45 scales (Table 3). Among them, two scales were listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1: ADAS-Cog and MMSE. The ADAS-Cog was most frequently employed, followed by the MMSE before and after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. Although ADAS-Cog was listed in both TAUG-AD 1.0 and TAUG-AD 2.0.1, its use was reduced by approximately 4% after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 (p=0.018). Also, the use of MMSE did not change after the release of the TAUGAD 2.0.1 (p=0.503). Among the scales not listed in the TAUGAD 2.0.1, the use of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment slightly increased after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1.

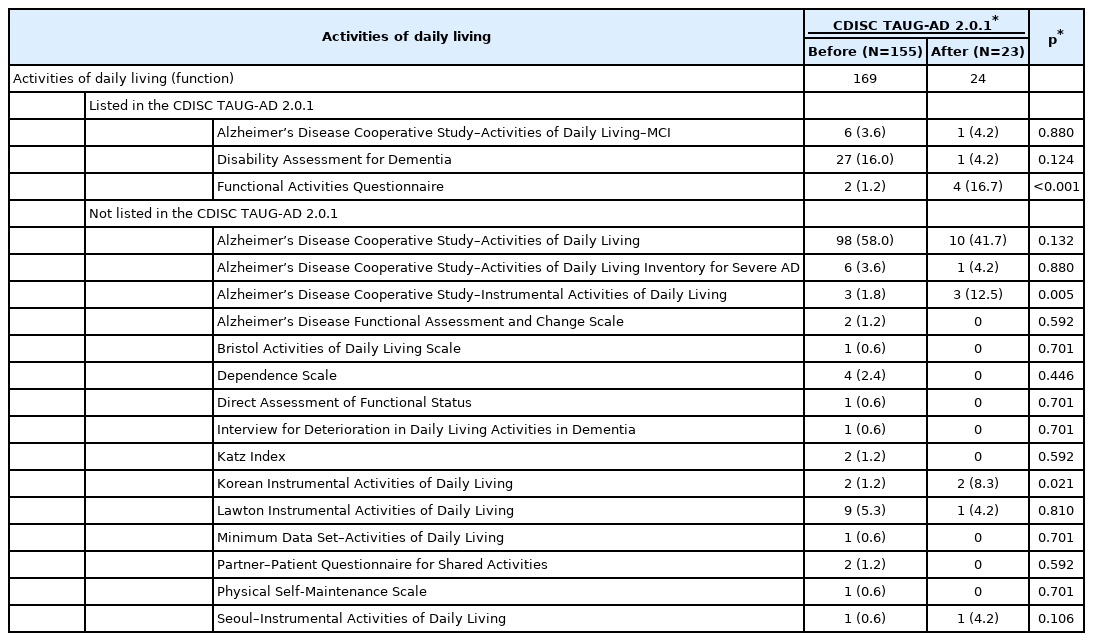

ADL (function)

To measure the ADL, 178 out of 305 protocols employed 18 scales (Table 4). Among them, three scales were listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1: ADCS-ADL-MCI, DAD, and FAQ. However, the most frequently employed scale in the clinical trials on AD was the ADCS-ADL28 before and after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. Although the use of ADCS-ADL was slightly reduced after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, approximately half of clinical trials on AD employed the ADCS-ADL to measure ADL. The DAD, which was the second most commonly employed scale before the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, became much less employed after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. In contrast, FAQ were more employed after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, making them the second most commonly employed scales following the ADCS-ADL after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 (p<0.001). In addition, the use of the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Instrumental Activities of Daily Living significantly increased, making it the third most commonly employed scale for measuring ADL after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1.

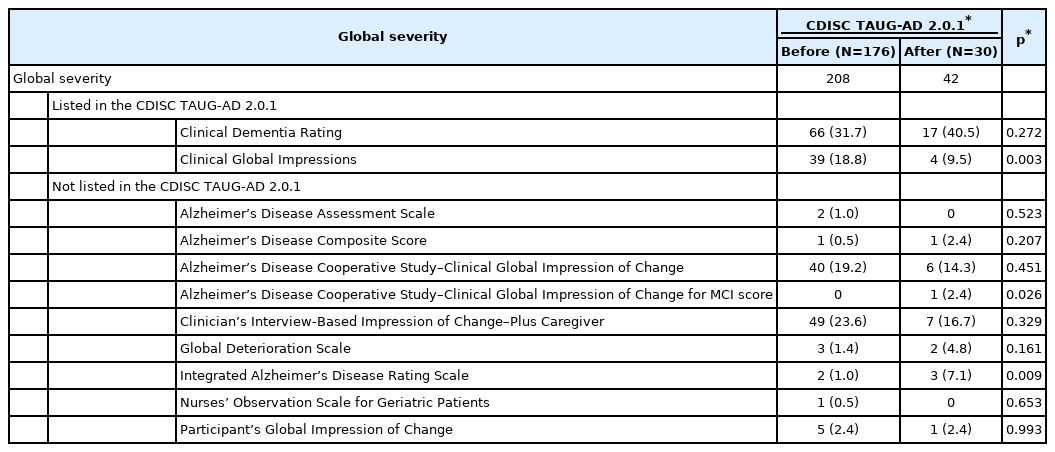

Global severity

To measure global severity, 206 out of 305 protocols employed 11 scales (Table 5). Among them, two scales were listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1: CDR and CGI. CDR was most frequently employed before and after the release of the TAUGAD 2.0.1. The second most commonly employed scale was the Clinician’s Interview-Based Impression of Change–Plus Caregiver (CIBIC-Plus) before the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. Although the use of CIBIC-Plus was reduced by half after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, it was not significant. Also, the use of CGI changed after the release of the TAUGAD 2.0.1, and it was reduced by half after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 (p=0.003).

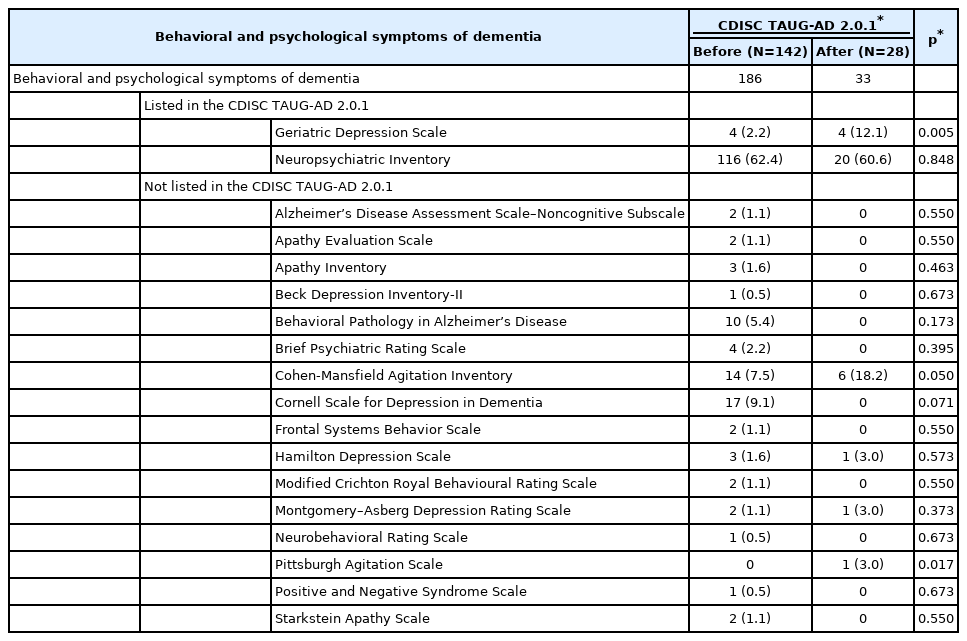

BPSD

To measure the BPSD, 170 out of 305 protocols employed 18 scales (Table 6). Among them, two scales were listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1: NPI and GDS. NPI was invariably the most frequently employed before and after the release of TAUGAD 2.0.1 and was employed in approximately 60% of trials. Before the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia was the second most commonly employed scale for measuring depressive symptoms, but it reduced after the release of TAUG-AD 2.0.1. However, the use of the GDS sextupled after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 (p=0.005). The use of the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) doubled after the release of the TAUGAD 2.0.1, and the CMAI become the second most commonly employed scale for measuring BPSD in trials on AD following the NPI.

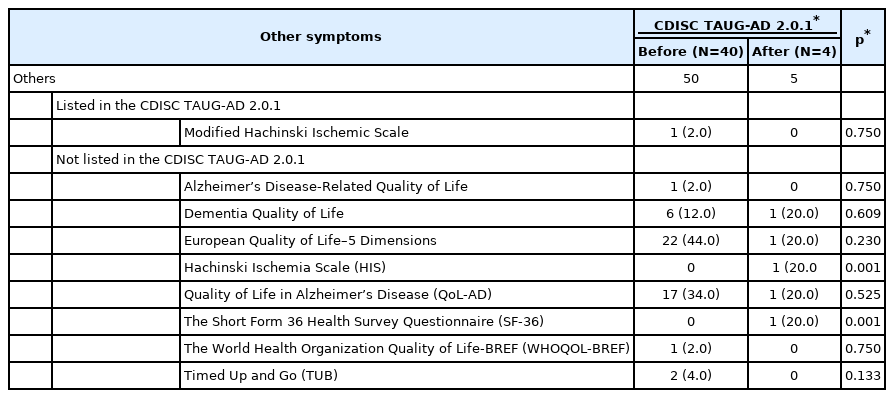

Other measures

The TAUG-AD 2.0.1 listed the MHIS, but the use of the MHIS was reduced in the clinical trials on AD after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, the difference was not statistically significant (Table 7). Although the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 did not recommend any measure for QoL, six scales for QoL were employed in the clinical trials. The European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) was the most frequently employed, followed by the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) before the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. However, after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, the use of the EQ-5D was almost halved, while that of the QoL-AD was also reduced (Table 7).

DISCUSSION

The CDISC provided investigators with the TAUG for AD to share common strategies in data standards for review, analysis of data, and submission to a regulatory agency for the clinical trials on AD. A previous systematic review identified the core outcomes from the National Institute for Health Researchfunded trials on of people with mild to moderate dementia [29]. Another study suggested primary and secondary endpoints for phase II/III trials on AD using the protocols registered in ClinicalTrials.gov [5]. However, it has never been investigated how well the clinical trials on AD registered in ClinicalTrials. gov complied with this guide. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation on how well the TAUG-AD proposed by the CDISC is accepted in the real-world clinical trials on AD.

Cognitive scales were the most commonly employed outcome measures in the clinical trials on AD. ADAS-Cog and MMSE, listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, were most commonly employed outcome measures for cognitive function in clinical trials, which was in line with a previous review. However, they had some limitations as an outcome measure for evaluating the efficacy in AD patients with a wide range of severity such as floor and ceiling effects and insensitivity to cognitive decline [29-32]. Although other cognitive measures such as Neuropsychological Test Battery [29,32,33] and Severe Impairment Battery [34] were developed to overcome such limitations of ADASCog and MMSE, they were not listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. The CDISC may need to consider specifying cognitive measures additionally to compensate for the shortcomings of ADASCog and MMSE in the subsequent version of TAUG-AD.

Although ADL scales became not employed as a primary outcome measure after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, its importance as an outcome measure in clinical trials on AD is increasingly emphasized [4,32]. Among the three ADL scales listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, FAQ was more frequently employed after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. A previous study recommended community-level ADL scales such as DAD rather than ADCS-ADL as an outcome measure for clinical trials on PwMMD [29,35]. However, the use of DAD was reduced by onefourth after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. ADCS-ADL is sensitive to modest functional impairment in people with MCI as well as in those with mild to moderate dementia [36]. As MCI and mild AD patients with biomarkers were considered the best targets in recent clinical trials such as that for anti-amyloid therapy [37], ADCS-ADL could be more employed than earlier.

BPSD measures as a primary endpoint doubled after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 in AD clinical trials. The lifetime risk of developing BPSD is 100% in AD [32]. NPI, listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, was the most frequently employed scale on BPSD in trials on AD before and after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. NPI takes less time to administer than other BPSD measures such as Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD) because it uses the screening methodology [23,29,38]. This could be why the NPI was far more frequently employed than the BEHAVE-AD despite BEHAVE-AD providing the severity of each BPSD symptom, which is not usually provided by the NPI [38,39]. Although nearly half of people with AD experience agitations [40], the TAUGAD 2.0.1 did not specify an instrument for measuring agitation. Although the CMAI was not included in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, its use was almost doubled after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, making it the second most commonly employed scale on BPSD in the clinical trials on AD, indicating a gap to be construed between the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 and the needs of clinical trials on AD.

The US FDA required global assessments as the primary outcome measure in anti-dementia drug trials [41,42]. The two global assessment scales listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, CDR and CGI, were the most widely employed in clinical trials on AD after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. CIBIC-Plus [43,44] and Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study–Clinical Global Impression of Change (ADCS-CGI) [45], although not listed in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1, were also commonly employed in clinical trials on AD before and after the release of TAUG-AD 2.0.1. The structures of the CIBIC-Plus and ADCS-CGI are similar: they require an independent clinician for assessment, interview both patients and informants, use semi-structured ascertainment methodologies to arrive at final severity assignments, and score the severity on a seven-point scale from marked improvement to marked worsening. However, the CGI does not have specific rules for ascertainment [44].

QoL is an important health outcome as the primary or secondary endpoints in clinical trials on AD and the measures for evaluating QoL in PWD have developed rapidly over the past 15 years [5,29]. However, CDISC did not list any scale on QoL in TAUG-AD. As PWD may lose their ability to measure QoL due to progressive loss of cognitive function, QoL measures that work well in a specific stage of dementia may not work in other stages [29]. Therefore, to measure QoL in PWD, dementia-specific measures such as QoL-AD, Dementia-Related Quality of Life (DEMQOL), AD-related QoL instrument, dementia QoL instrument, and QoL assessment schedule [46] are more suitable than general measures such as the EQ-5D or Short Form Health Survey [29,47,48]. The use of DEMQOL increased and doubled, while that of EQ-5D was halved after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. The CDISC should consider specifying a disease-specific QoL scale such as the DEMQOL in their next version of TAUG-AD.

This study has several limitations. First, the changes in the use of scales after the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1 do not necessarily indicate that the changes are attributable to the release of the TAUG-AD 2.0.1. Second, we did not conduct a systematic review to identify the outcome measures used in AD research. However, by including the protocols registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, we could reduce the publication bias and identify the actual outcome measures employed in clinical trials on AD. Third, we did not examine the changes with regard to the use of biomarkers that were included in the TAUG-AD 2.0.1.

Despite these limitations, this study examined a comprehensive review of the primary and secondary endpoints used in the actual clinical protocols and provided evidence for a common or preferred outcome measure that could be considered in designing or standardizing clinical data models. Researchers may refer to the TAUG-AD to select proper outcome measures for designing clinical trials on AD, if the gap between TAUG-AD and real-world clinical trials observed in the current study is filled. Furthermore, researchers may consider integrating several clinical data on AD and use it to develop drug development tools. Using standardized clinical data models, a previous study could build integrated databases for the generation of drug development tools, such as polycystic kidney disease [49]. They used CDISC SDTM and the polycystic kidney disease-TAUG to map data from several academic registries and natural studies, and they developed a joint biomarker dynamics and disease progression model to demonstrate the relationship between total kidney volume and loss of kidney function by using integrated datasets [49,50]. By using structured and standardized data models and outcome measures on AD trials, the integration of several clinical trials on AD will be effective.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available in the ClinicalTrials.gov repository, https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

Conflicts of Interest

Ki Woong Kim, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ki Woong Kim, Riyoung Na, Jong Bin Bae. Data curation: Riyoung Na, Sue Hyun Jung. Formal analysis: Riyoung Na. Investigation: Riyoung Na, Sue Hyun Jung. Methodology: Ki Woong Kim, Riyoung Na. Project administration: Jong Bin Bae. Supervision: Ki Woong Kim. Writing—original draft: Riyoung Na, Jong Bin Bae. Writing—review & editing: Riyoung Na, Jong Bin Bae, Ki Woong Kim.

Funding Statement

None