|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 20(4); 2023 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

Methods

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary┬ĀMaterial

Supplementary┬ĀTable┬Ā1.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The data that support the findings of study are available from the corresponding author (JM Kim) upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Jae-Min Kim declares research support in the last 5 years from Janssen and Lundbeck. Sung-Wan Kim declares research support in the last 5 years from Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Allergan and Otsuka. Jae-Min Kim, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Jae-Min Kim. Data curation: Jae-Min Kim. Formal analysis: Jae-Min Kim, Hee-Ju Kang. Funding acquisition: Jae-Min Kim. Investigation: Jae-Min Kim, Sung-Wan Kim. Methodology: Jae-Min Kim, Hee-Ju Kang, Ju-Wan Kim, Wonsuk Choi. Project administration: Jae-Min Kim, Youngkeun Ahn, Myung Ho Jeong. Resources: Jae-Min Kim. Software: Jae-Min Kim. Supervision: all authors. Validation: Jae-Min Kim, Hee-Ju Kang, Ju-Wan Kim. Visualization: Jae-Min Kim, Ye Jin Kim. WritingŌĆö original draft: Jae-Min Kim, Hee-Ju Kang. WritingŌĆöreview & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

The study was funded by a grant of National Research Foundation of Korea Grant [NRF-2020M3E5D9080733] and [NRF-2020R1A2C2003472].

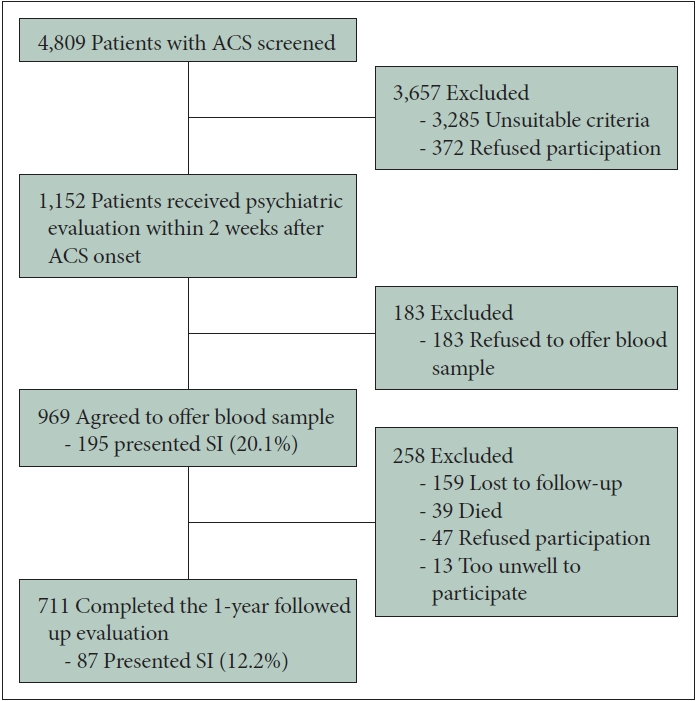

Figure┬Ā1.

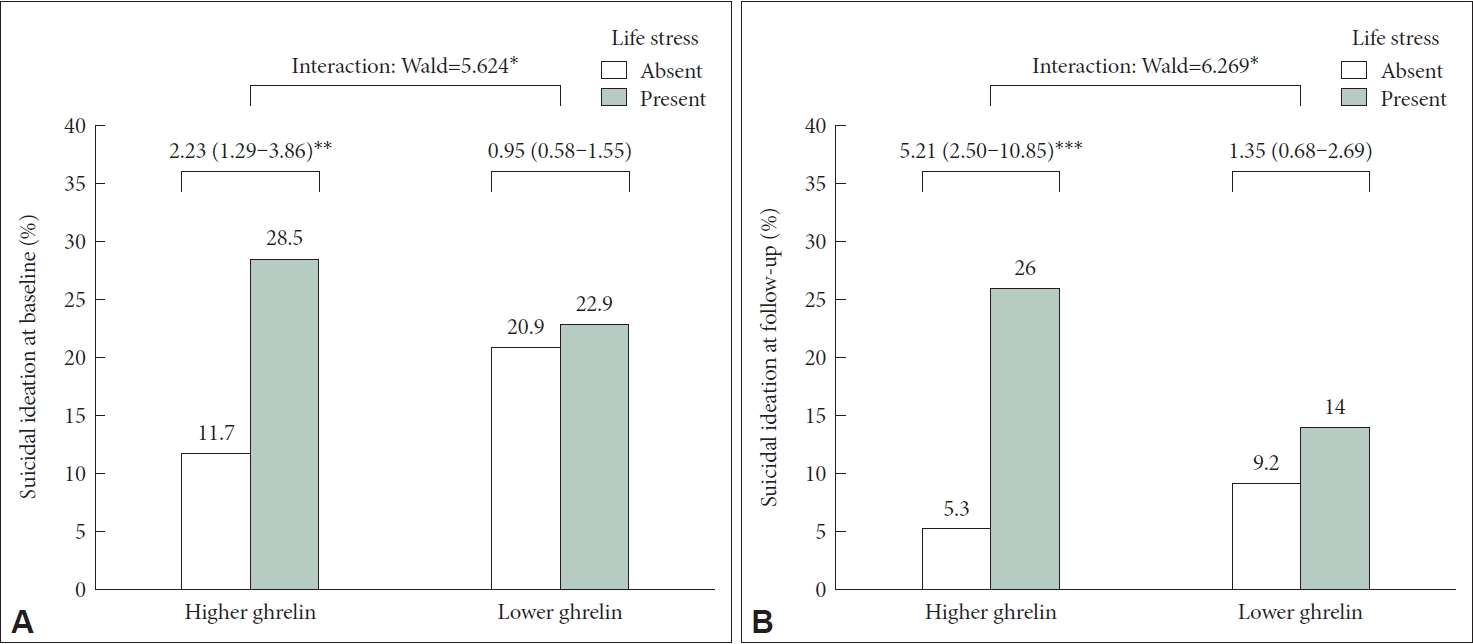

Figure┬Ā2.

Table┬Ā1.

| Exposure | Group |

SI at baseline |

SI at follow-up |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | SI presence |

OR (95% CI) |

Total | SI presence |

OR (95% CI) |

||||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||

| Life stress | Absent | 545 | 87 (16.0) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 409 | 29 (7.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Present | 485 | 108 (25.5) | 1.80 (1.31-2.47)*** | 1.35 (0.95-1.93)** | 302 | 58 (19.2) | 3.12 (1.94-5.00)*** | 2.72 (1.68-4.43)*** | |

| Ghrelin (pg/mL) | Higher (Ōēź420) | 484 | 89 (18.4) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 356 | 46 (12.9) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Lower (<419) | 485 | 106 (21.9) | 1.24 (0.91-1.70) | 1.15 (0.81-1.64) | 355 | 41 (11.5) | 0.88 (0.56-1.38) | 0.82 (0.52-1.31) | |

Values are presented as number or number (%). Adjusted odd ratios (ORs) (95% confidence intervals [CIs]) were estimated adjustment for sex, education, housing, current employment, previous and family history of depression, present clinical depression, family history of ACS, and serum troponin I levels.

REFERENCES

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- Scopus

- 1,852 View

- 34 Download

-

BDNF Methylation and Suicidal Ideation in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome2018 October;15(11)