Children’s and Parents’ Factors That Affect Parenting Stress in Preschool Children With Developmental Disabilities or Typical Development

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study compared parenting stress in preschool children with developmental disabilities (DD) or typical development (TD). We also investigated children’s factors that affect parenting stress.

Methods

A total of 196 preschool children participated in the study (aged 54.8±9.2 months). There were 79 children with DD (59 with autism spectrum disorder, 61 with intellectual disability, 12 with language disorder) and 117 with TD. The high parenting stress and the low parenting stress groups were divided based on the Total Stress of Korean Parenting Stress Index Fourth Edition (K-PSI-4) with an 85-percentile cutoff score. Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to calculate the correlation between K-PSI-4 and the children’s or parents’ measures.

Results

The difference in parenting stress between DD and TD was significant in the Total Stress of K-PSI-4 (p<0.001). The Total Stress scale of K-PSI-4 represented a modest to strong correlation with cognitive development, adaptive functioning, social communication, and behavioral problems in children with DD. Our results showed that caregivers of children with DD reported higher parenting stress than those with TD. Parenting stress was strongly associated with cognitive development, adaptive functioning, social communication, and behavioral problems in children with DD. Among the children’s factors, especially social communication, attention problems, and aggressive behavior had association with caregivers’ higher parenting stress.

Conclusion

These findings suggest the need for early intervention for parenting stress in caregivers by assessing child characteristics, including social cognition, awareness, communication, and inattention and hyperactivity, in the evaluation of children with DD.

INTRODUCTION

Developmental disabilities (DD) including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and intellectual disability (ID) are neurodevelopmental disorders that occur during the developmental period [1]. DD is a lifelong disorder that is challenging to treat, and the medical cost of treatment is significant. DD is frequently accompanied by behavioral, emotional or sleep problems, making therapeutic access more difficult [2,3]. Caregivers of children with DD are also known to report heightened parenting stress levels than those with typical development (TD) [4-7].

Parenting stress is a negative psychological reaction that caregivers experience when they perceive that the need to take care of their children exceeds their resources [8]. Parenting stress includes insufficient ability to care for children, a negative assessment of their interactions with children, and the experience of excessive child needs [9]. Parenting stress for caregivers of DD children increases when a child fails to reach the expected development in cognition, behavior, social interaction, or communication skills [10,11]. Many studies have reported that caregivers of children with DD have more mental health problems including depression and anxiety, and low quality of life than caregivers of children with TD [12-15]. Caregivers of children with DD experience additional economic burdens, more restrictions in their social activities [16]. Children with DD are more likely to have a family environment with a higher level of parenting stress than children with TD [7,17]. High parenting stress is known to increase behavioral problems in children, and behavioral problems in children further increase parenting stress over time [6,18].

Previous research has shown that parenting stress is primarily determined by parent and child factors. Child factors include the child’s distractibility, hyperactivity, demands, and mood symptoms, and parent factors include parent’s competence, attachment, health, depression, and the relationship between parenting partners [19]. In children with DD, child factors such as severity of autism symptoms, behavioral problems, and/or developmental level have been reported to increase parenting stress [20,21]. In particular, maladaptive behaviors in children with DD been found to be correlated with parenting stress [22-26]. Recent studies suggest that parents’ factors and child-parent interactions also influence parenting stress in children with DD [27-29]. Although there has been much research on child and parent factors affecting parenting stress, the results are conflicting and inconsistent [22,30]. Therefore, further research is still needed on factors affecting parenting stress in children with DD.

Most studies assessing parenting stress in children with DD have used parent rating scales of child developmental levels, characteristics, and behaviors [31]. Caregivers with higher levels of parenting stress rate their children’s problem behaviors as more severe [32]. Therefore, there is potential for a discrepancy between parental ratings of children’s behavior and ratings by non-parental raters (e.g., teacher, clinician) [33,34]. On the other hand, assessments of children’s developmental levels, such as language, did not differ significantly between parent and non-parent raters [32]. Given these limitations, this study sought to evaluate the impact of child characteristics on parenting stress by assessing both parent-reported measures and the child’s developmental level directly by raters.

The purpose of this study is to identify whether parenting stress experienced by caregivers of children with DD is significantly higher than that experienced by caregivers of TD children. We also aimed to determine which child and parent factors contribute to the high parenting stress among caregivers of DD.

METHODS

Participants and procedure

A total of 196 children were recruited from May 2020 to July 2020 at community-based daycare centers, kindergartens, and special education centers. Information on the research were noticed in each center, and children were enrolled if the children and their caregivers agreed to participate in the study. Enrolled children were between 34 and 77 months of age. Children were excluded from the study if they had 1) a history of neurologic disease such as cerebral palsy, 2) any sensory disturbances (i.e., vision, hearing, taste, or smell), or 3) severe gross or fine motor problems that prevented them from participating in the psychometric tests. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center (IRB no. 2020-0386), and written informed consent was obtained from the caregivers of each child.

Of the 196 subjects that were recruited, 79 children had DD, and 117 children had TD. DD included ASD, ID, and language disorder in which a diagnosis was confirmed by board-certified child and adolescent psychiatrists based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [1] diagnostic criteria and relevant psychometric tests. Subsequently, a consensus meeting involving two or three child and adolescent psychiatrists took place to confirm the diagnosis.

Assessment and measures

Cognitive development

Psychoeducational Profile-Revised (PEP-R) assesses seven domains of development: Imitation, Perception, Fine Motor, Gross Motor, Eye-hand Coordination, Cognitive Performance, and Cognitive Verbal Performance. Previous studies reported that the PEP-R shows good internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and high concurrent validity with the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale [35,36]. The Developmental Quotient (DQ) was calculated to assess the overall developmental level ([developmental age/chronological age]×100) [37,38].

Adaptive functioning

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale, Second Edition (VABS), which is a semi-structured interview, was administered to estimate adaptive functioning. Overall standard Adaptive Behavior Composite Score (ABCS) and standardized scores for four domains were obtained. Standardized scores have a mean value of 100±15 and higher scores indicate a higher level of functioning. The VABS demonstrated good-to-excellent test–retest reliability and modest concurrent validity [39,40].

ASD characteristics

The Korean version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (K-CARS) was administered by child psychologists to assess the ASD characteristics. The K-CARS consists of 15 items rated on a 7-point scale with scores ranging from 1 to 4 (half points), in which higher total scores indicate higher severity [21,41]. In addition, the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), a parent-completed 65-item questionnaire, was used to measure the frequency of ASD-related behaviors [42].

Behavioral problems

Behavioral and emotional problems were measured by the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 1.5–5 (CBCL) and the Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC). CBCL 1.5–5 is a 99-item scale rated by parents with scores ranging from 0 to 2 for each item [43]. The scores for the following seven subscales were calculated: Emotionally Reactive, Anxious/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Withdrawn, Sleep Problems, Attention Problems, and Aggressive Behaviors. CBCL demonstrated good reliability and validity in clinical and nonclinical populations and showed good cross-informant agreement [43,44].

ABC, which is a rating scale used to assess behavioral problems in individuals with DD, was also administered. The ABC consists of 58 items answered on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3 based on problem severity. The items are further categorized into the following five domains: Irritability, Lethargy/Social Withdrawal, Stereotypic Behavior, Hyperactivity/Noncompliance, and Inappropriate Speech. The psychometric properties of ABC have been assessed, and the subscales showed high internal consistency, adequate reliability, and established validity [45,46].

Parenting stress and depression

Parenting stress and depression were measured using the Korean version of Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition (K-PSI-4) and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised (CESD-R), respectively [47]. The K-PSI-4 is a 120-item measure with two domains: 1) the Child domain and 2) the Parent domain. The Child domain reflects stress arising from parents’ reports of child characteristics and consists of six subscales: Distractibility/Hyperactivity, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, Demandingness, Mood, and Acceptability. The Parent domain consists of seven subscales: Competence, Isolation, Attachment, Health, Role restriction, Depression, and Spouse relationship. Scores from both domains can be summed to produce the Total Stress of PSI. Both Child and Parent domain showed excellent internal consistency, and the K-PSI-4 displayed predictive validity in studies performed in other countries [19,48]. The CESD-R consists of 20 items related to depression rated on a 5-point scale based on symptom frequency. CESD-R showed good psychometric properties, including high internal consistency, and consistent convergent and divergent validity [47].

Statistical analyses

The chi-squared test was used for categorical variables and the independent t-test for continuous variables. To examine the correlation between the subscales of PSI and children’s measures, Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated, and significant correlations were identified (p<0.05). We used multiple regression analysis to determine which children’s measures have the greatest influence on parenting stress. Age, sex, and socioeconomic status that showed significant (p<0.05) difference between groups were included in the multiple linear regression model. To detect collinearity, variance inflation factors (VIFs) and correlations between variables were assessed. All included variables showed a VIF value <10 and a correlation <0.80, suggesting low concern for collinearity [49,50].

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and R software (version 4.2.1, R packages; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [51]. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value of less than 0.05, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of children and parents

The overall characteristics of the study sample are summarized in Table 1. A total of 196 children were recruited; of these, 79 children were categorized as DD, and 117 children were categorized as TD. Among 79 children with DD 59 children were diagnosed with ASD, 61 with ID, and 12 with LD. Significant difference in age (p<0.001), sex (p=0.045), and socioeconomic status (p=0.015) existed between the DD and TD groups. Thus age, sex, and socioeconomic status were controlled for further analyses. PEP-R DQ, VABS ABCS, K-CARS, ABC total score, SRS total score, CBCL internalizing and externalizing score, and caregiver CESD-R were significantly different between the DD and TD groups (all p<0.001).

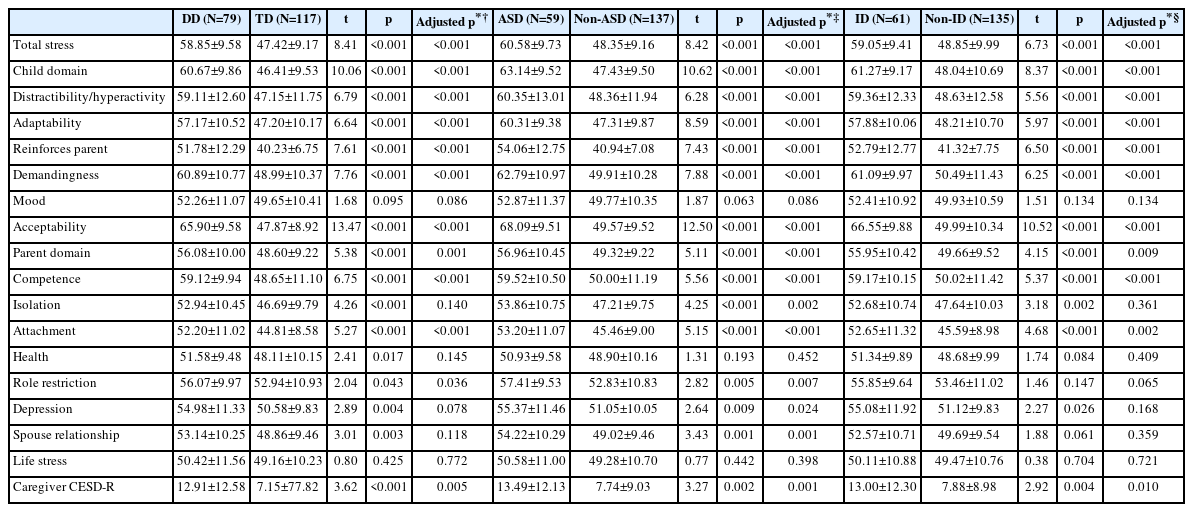

Comparison of parenting stress between DD and TD

The PSI subscales were compared between the children with DD and TD (Table 2). After adjusting for age, sex, and socioeconomic status, children with DD scored significantly higher on the Total Stress of PSI than children with TD (adjusted p<0.001). The PSI subscales including Distractibility/hyperactivity, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, Demandingness, and Acceptability of Child domain (all adjusted p<0.001), and the Competence, Attachment, and Role restriction of Parent domain (all adjusted p<0.05) were all higher in children with DD than those with TD.

After adjusting for age which were different between the ASD and non-ASD groups (p<0.001), children with ASD showed significantly higher parenting stress than children without ASD on the Distractibility/hyperactivity, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, Demandingness, and Acceptability of Child domain, the Competence, Isolation, Attachment, Role restriction, Depression, and Spouse relationship of Parent domain, and the Total Stress. After adjusting for age and socioeconomic status which showed significant difference between the ID and non-ID groups, Children diagnosed with ID showed significantly higher parenting stress than children without ID on the Distractibility/hyperactivity, Adaptability, Reinforces parent, Demandingness, and Acceptability of Child domain (all adjusted p<0.001), and the Competence (adjusted p<0.001) and Attachment (adjusted p=0.002) of Parent domain.

Comparison of child scores between the high and low parenting stress groups

To examine the difference between the high and low parenting stress groups, the Total Stress of PSI cutoff of >85 percentile was defined (Table 3). Significant differences in age (p=0.002) existed between the high and low parenting stress groups, and age was controlled for analyses. When compared to the low parenting stress group, the high parenting stress group scored significantly higher on the PEP-R DQ and all seven domains of PEP-R (all adjusted p<0.001), VABS ABCS (adjusted p<0.001), K-CARS (adjusted p<0.001), and the total score and all five domains of SRS (all adjusted p<0.001). The total score, Irritability, Lethargy/Social Withdrawal, Hyperactivity/Noncompliance, and Inappropriate Speech (all adjusted p≤0.001), and Stereotypic behavior (adjusted p=0.014) of ABC showed significant differences in the high parenting stress group. Except for the Somatic Complaints (adjusted p=0.135), all subscales of CBCL were significantly higher in the high parenting stress group (all adjusted p≤0.001).

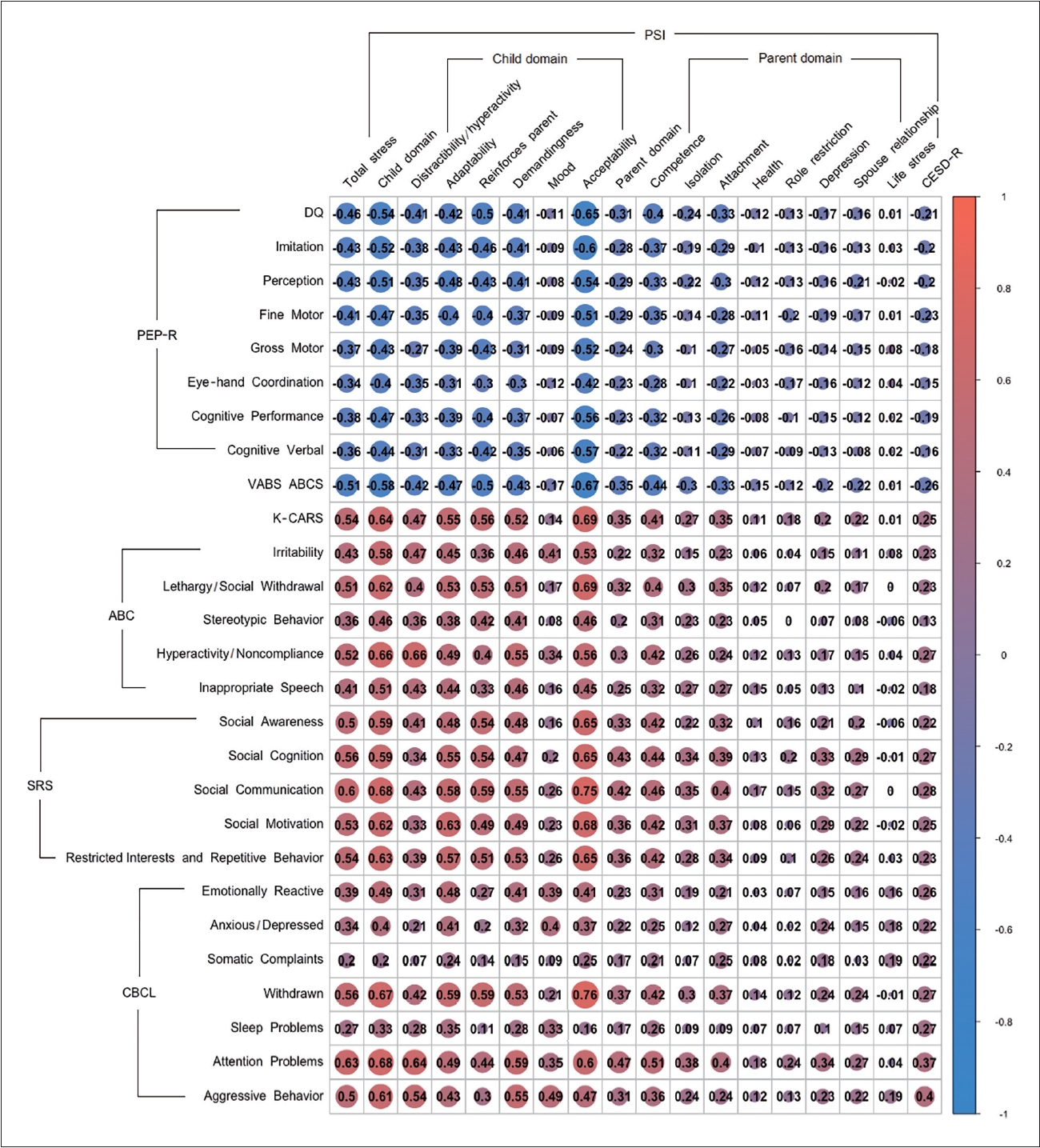

PSI score and the children’s behavioral and cognitive measures

The correlation between the Total Stress score, Child domain, Parent domain, each of the 17 PSI subscales and CESD-R, and each of the children’s behavioral and cognitive measures was calculated (Figure 1). The Child domain score of PSI represented a strong correlation with the K-CARS (r=0.64), Lethargy/Social Withdrawal and Hyperactivity/Noncompliance of ABC (r=0.62 and r=0.66, respectively), Social Communication, Social Motivation, and Restricted Interests and Repetitive Behavior of SRS (r=0.68, 0.62, and 0.63, respectively) and the Withdrawn, Attention Problems, and Aggressive Behavior of CBCL (r=0.67, 0.68, and 0.61, respectively). The Child domain score represents modest to strong correlation with the all subscales of PEP-R and PEP-R DQ (-0.4<r<-0.54), VABS ABCS (r=-0.58), all subscales of ABC (0.46<r<0.66), all subscales of SRS (0.59<r<0.68), and the Emotionally Reactive, Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn, Attention Problems, and Aggressive Behavior of CBCL (r=0.49, 0.4, 0.67, 0.68, and 0.61, respectively). Especially, the Acceptability score of Child domain showed a strong correlation with the PEP-R DQ, VABS ABCS, K-CARS, the Lethargy/Social Withdrawal of ABC, the Withdrawn of CBCL (r=-0.65, -0.67, 0.69, 0.69, and 0.76, respectively), and all subscales of SRS (all r≥0.65). The Parent domain score of PSI showed modest correlation with the Social Cognition, Social Communication of SRS, and Attention Problems of CBCL (r=0.43, 0.42, and 0.47, respectively). In TD (Supplementary Figure 1 in the online-only Data Supplement) and DD (Supplementary Figure 2 in the online-only Data Supplement), there was also an association between parenting stress and child measures, respectively.

Correlation of parenting stress and child measures in DD and TD. PSI, Parenting Stress Index; CESD-R, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised; PEP-R, Psychoeducational Profile Revised; DQ, Developmental Quotient; VABS ABCS, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale Adaptive Behavior Composite Score; K-CARS, Korean version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale; ABC, Aberrant Behavior Checklist; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; DD, developmental disabilities; TD, typical development.

Hierarchical multiple linear regression was conducted to identify variables that were significantly associated with the Total Stress of PSI (Table 4). Stepwise regression model was built, we included for age, sex, and socioeconomic status in the first step to control for the possible confounding influence on parenting stress. The final model included age, sex, socioeconomic status, the Social Communication, Social Awareness, and Social Cognition of SRS, and the Attention Problems and Aggressive Behaviors of CBCL. Of the variables included in the final model, higher scores on the Social Communication of SRS, Attention Problems and Aggressive Behaviors of CBCL, and the Social Awareness, and Social Cognition of SRS were significantly associated with the parenting stress in order (β=0.418, 0.280, 0.170, -0.240, and 0.201, respectively, and all p<0.02).

DISCUSSION

In our study, caregivers of children with DD experienced higher stress levels than those of children with TD. The study also showed that parenting stress was strongly associated with cognitive development, adaptive functioning, social communication, and behavioral problems, especially in children with DD.

This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that families with children with DD report high parenting stress rates [6,52-54]. Researchers have found that caregivers of children with DD have high rates of depression and anxiety [55] and a lower quality of life [56]. Parenting stress makes caregivers vulnerable to mental health problems, and caregivers’ mental health problems exacerbate parenting stress, which in turn affects each other [8,31]. Reducing parenting stress is a key way to mitigate the impact of behavior problems, so clinicians should consider ways to reduce parenting stress.

A second finding of this study was that among the child measures, Social Communication, Social Awareness, and Social Cognition of the SRS and Attention Problems and Aggressive Behaviors of CBCL were found to be the most significant contributors to parenting stress. Child’s social development and behavioral problems are two major factors that contribute to parenting stress for preschool children with DD.

A parent of a child with DD who lacks social awareness and social cognition may feel more burdened, resulting in increased parenting stress. Past researches have shown that impaired social communication is one of the most stressful aspects of parenting for caregivers of children with DD [20,21]. One study reported that children’s delays/deficits in social skills and social relatedness were the most consistent predictors of parenting stress in children with DD [57]. When children are not socially engaged in their interactions with caregivers, caregivers may feel that their efforts are not reciprocated, which can have a significant impact on parenting stress. For example, children with Down syndrome tend to be more sociable than other DDs, which can be more rewarding for caregivers, resulting in less parenting stress [58]. Caregivers of children with DD who exhibit significant social impairment need to be assessed early for parenting stress and provided with appropriate social support.

Children with DD who exhibited emotional and behavioral problems such as aggressive behaviors, hyperactivity, distractibility, demandingness, and stubbornness had higher levels of parenting stress. Behavioral problems in children with DD can cause caregivers to experience emotional burnout, which is associated with depression, anxiety, and parenting stress [4,59]. Previous research has shown that children’s emotional problems and aggressive behaviors are strong predictors of parenting stress [22,60]. Emotional and behavioral problems in children with DD increase parenting stress, which in turn impairs the caregiver’s ability to provide positive parenting, resulting in more emotional and behavioral problems in the child [31,59]. These findings suggest early assessment of behavioral problems in children with DD to reduce caregiver stress. Paying attention to symptoms related to children’s social interaction and behavioral problems will be a useful way to prevent dysfunctional parenting in high-risk groups of parenting stress.

All subscales of the Child domain of PSI except for the Mood subscale, were significantly higher for children with DD than for children with TD in our study. These results were consistent when comparing ASD to non-ASD and ID to non-ID. For children with DD who score high on the Child domain of the PSI, this suggests that the child’s characteristics as perceived by the caregiver may contribute to parenting difficulties and that interventions focused on the child’s behavior are needed. High scores on the child domain may reflect both increased parenting stress and low parenting competence, leading to more behavioral problems in the child [9,19]. Child characteristics such as cognitive, emotional, and behavioral differences from parental expectations, particularly observed in children with DD, are potential sources of parenting stress.

The Parent domain represents that parents feel burdened by parenting and evaluate themselves as insufficient. Among the subscales of the Parent domain, DD and TD showed differences in Competence and Attachment in this study. ASD and non-ASD differed on Competence, Isolation, Attachment, and Spouse relationship, while ID and non-ID differed only on Competence and Attachment and, unlike ASD, did not differ on Isolation or Spouse relationship. The Isolation indicates stress due to the parenting role as well as psychological distress such as neglect or rejection experienced by the parent [61]. This suggests that caregivers of children with ASD are significantly more likely to be socially isolated than caregivers of children with other DD. Caregivers of children with ASD are more likely to feel controlled by their child’s needs than caregivers of individuals with ID. In previous studies, parents of children with autism seem to experience even more stress than parents of children with other disabilities [5,62]. High levels of social support for caregivers have been associated with lower levels of parenting stress [11]. In addition, relationship quality buffers the effect of parenting stress on parental depression [62]. To reduce the stress of parenting children with ASD, caregivers need sufficient social support.

There are several limitations to consider in this study. First, the influence of external factors other than children and parents, such as mental health services, was not examined. Considering the situation in Korea, parents bear a considerable financial burden to provide special education to DD children. The additional economic burden caused by special education can act as an external factor affecting parenting stress. Second, this study was a cross-sectional study, and it was not possible to examine the longitudinal interaction between parents and children. According to this study, parenting stress was associated with children’s behavioral problems and social adaptations. Recent studies indicate that children’s characteristics do not increase parenting stress in one direction, but rather demonstrate the continuous interaction between children and parents [28,29]. Therefore, it is important to consider the reciprocal relationship when interpreting the high association between parenting stress and child characteristics. Third, the use of a parent-report scale of emotional and behavioral problems can lead to bias based on parents’ subjective experiences with their children or parental depression [63]. Therefore, ratings of emotional and behavioral problems or social impairment in children with DD need to be assessed not only by parents but also by non-parent raters such as clinicians and teachers [32,64].

Conclusions

These findings suggest the need for early intervention for parenting stress in caregivers by assessing child characteristics, including social cognition, awareness, communication, and inattention and hyperactivity, in the evaluation of children with DD. Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of early intervention programs on parenting stress.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2023.0223.

Correlation of parenting stress and child measures in TD. CESD-R, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised; PEP-R, Psychoeducational Profile Revised; DQ, Developmental Quotient; VABS ABCS, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale Adaptive Behavior Composite Score; K-CARS, Korean version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale; ABC, Aberrant Behavior Checklist; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; TD, typical development.

Correlation of parenting stress and child measures in DD. CESD-R, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale-Revised; PEP-R, Psychoeducational Profile Revised; DQ, Developmental Quotient; VABS ABCS, Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale Adaptive Behavior Composite Score; K-CARS, Korean version of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale; ABC, Aberrant Behavior Checklist; SRS, Social Responsiveness Scale; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; DD, developmental disabilities.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyo-Won Kim. Data curation: Taeyeop Lee, Jichul Kim. Formal analysis: Eunji Jung, Taeyeop Lee. Funding acquisition: Hyo-Won Kim. Methodology: Taeyeop Lee. Project administration: Hyo-Won Kim. Resources: Hyo-Won Kim. Software: Taeyeop Lee. Supervision: Hyo-Won Kim. Validation: Hyo-Won Kim. Visualization: Eunji Jung. Writing—original draft: Eunji Jung. Writing—review & editing: Hyo-Won Kim.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (NRF-2020R1A5A8017671).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the children and families who participated in this research. This research would not have been possible without their involvement.