Protective Behaviors Against COVID-19 and Related Factors in Korean Adults With Depressive Symptoms: Results From an Analysis of the 2020 Korean Community Health Survey

Article information

Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated protective behaviors against coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) and related factors in individuals with depressive symptoms.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included data from the 2020 Korean Community Health Survey. Depressive symptoms, COVID- 19 protection behaviors, and related factors were investigated in 228,485 people. Chi-square test and logistic regression analysis were used to analyze categorical variables. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 27.0).

Results

In the study, 3.9% (n=8,970) had depressive symptoms. The prevalence of depressive symptoms was higher in individuals in their 19–39 years , and ≥60s than in those in their 40–59 years (p<0.001). Lower education level and household income were associated with a higher prevalence of depression (p<0.001). Among the various occupations, service workers had the highest prevalence of depressive symptoms (p<0.001). Individuals with depressive symptoms were less likely to adopt protective behaviors against COVID-19 (p<0.001) or exhibit concerns regarding death and economic damage (p<0.001) compared to individuals without depressive symptoms. Individuals with depressive symptoms were more likely to have unhealthy behaviors than those without depressive symptoms (p<0.001). Individuals with depressive symptoms considered that the COVID-19 response by the government and other organizations was inadequate (p<0.001).

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals with depressive symptoms faced greater challenges in adopting protective behaviors. Therefore, it is crucial to develop strategies to protect people with depressive symptoms during another pandemic in the future.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple studies have evaluated the effects of the ongoing coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on mental health [1,2]. According to the World Health Organization, the worldwide prevalence of major depressive disorder increased by 27.6% in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. The prevalence of depression reported in many countries by 2022 was found to range from 7.45 to 55% [4,5]. An online study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic found that prevalence of depression among Koreans was 18.8% [6]. Factors for increasing depression were considered to be factors relating to infectious diseases, social isolation, social distancing, fear of infection, and decline in economic activity [7].

The physical and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic may be more pronounced on individuals with preexisting mental disorders [8]. Depression adversely affects mental and physical health and social and financial well-being of individuals and societies [9]. Individuals with depressive symptoms exhibit mental, physical, social, and economic vulnerabilities, which are associated with increased risk of infection [10,11]. A study examining the effect of COVID-19 infection on mortality and hospitalization rates among patients with mental disorders found increased risk of infection among such individuals, particularly those with depression [12].

In individuals with depression, multiple factors can increase the risk of contracting COVID-19 and experiencing adverse outcomes [13]. They include difficulties in evaluating health information, adhering to preventive behaviors, limited healthcare access, and homelessness or residing in communal settings [12,14]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several infection prevention measures were implemented worldwide: 1) seeking medical attention or undergoing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing when contracted with fever or respiratory symptoms, or when a person has traveled abroad in the previous fortnight, 2) maintaining physical distance from others, 3) washing and disinfecting hands frequently using a hand sanitizer, and 4) wearing masks indoors [15,16]. Individuals with depression are less likely to adopt healthy habits, such as wearing masks, frequent handwashing, and avoiding large gatherings, thereby increasing their risk of contracting COVID-19 [17,18].

Most studies on COVID-19 and mental health have focused on the increase in prevalence of mental health issues and associated factors following the onset of the pandemic. However, few have evaluated the behaviors of individuals with mental health problems in response to the pandemic. This study aims to fill this gap in the literature by 1) evaluating the effects of depressive symptoms in individuals on their adoption of protective behaviors against COVID-19 and 2) exploring related factors.

METHODS

Data source and participants

Data for this study were sourced from the 2020 Korean Community Health Survey (KCHS), a cross-sectional nationwide health interview survey conducted annually by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) to evaluate disease prevalence, morbidity, lifestyle factors, and health behaviors. Raw data were downloaded after accessing the KDCA website [19] and approval for using the same was obtained. This survey is conducted to determine the health status of local residents and to gather statistical data for establishing evidence-based health policies. The target population of the survey was adults aged ≥19 years residing in apartments or general houses in the Republic of Korea at the time of the survey (conducted on August 16th every year) [20]. In total, 228,485 participants completed the survey in 2020. Sampling was conducted using resident registration address data from the Ministry of the Interior and Safety of the Republic of Korea. The sample size was determined based on an average of 900 people per local public health center, with an average margin of error of ±3%. The final sample was selected using a combination of the proportional distribution of the sample points and phylogenetic sampling techniques. The study design and data analysis protocol were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daejeon Eulji Medical Center, Eulji University (EMC 2022-02-020).

Measures

The KCHS involved visits to selected households by interviewers trained to conduct one-on-one interviews. The interviews typically lasted for 20–30 min per participant [20]. In screening for depression, the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used, which incorporates the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. The PHQ-9 consists of nine items that assess the frequency of depressive symptoms over the two weeks prior to the survey (with a score range of 0–27 points). In the present study, a cutoff score of 9 points was used to screen for depression based on the findings of recent Korean studies [21,22].

In the survey, the following were assessed: adoption of protective behaviors and four related factors, which include adhering to recommendation, concerns, lifestyle changes, and response appropriateness. Participants were assessed on adopting protective behaviors based on whether they were maintaining social distancing, refraining from visiting hospitals, and avoiding going out. The responses were categorized as “well followed” or “not well followed.” To evaluate adherence to the recommendations, participants were asked if they maintained frequent contact with individuals close to them, which is recommended for prevention of psychological issues. The responses were categorized as “yes” or “no.” Participants were asked about their concerns about being blamed for spreading infection, infected people around them in poor health, and the economic costs involved. Their responses were categorized as “yes” or “no.” Lifestyle changes were evaluated in terms of their physical activity, sleeping time, intake of instant and delivery food, number of alcoholic drinks consumed, and number of cigarettes smoked. The responses were categorized as “healthy” or “unhealthy.” Furthermore, participants were asked to evaluate the adequacy of the response to infectious disease outbreaks by the government, local government, mass media, local medical institutions, neighbors, and co-workers. The responses were categorized as “appropriate” or “inappropriate.” Additionally, sociodemographic data on sex, age, marital status, educational level, occupation, and monthly household income were obtained.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square or Student’s t-test was used to identify sociodemographic factors, protective behaviors, and related factors potentially associated with depression (PHQ-9 score ≥9). Logistic regression was used to obtain adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for protective behaviors and other factors related to depressive symptoms. The logistic regression model included control variables that were significant in the univariate analysis, including sex, age, marital status, educational level, occupation, and monthly household income. A p<0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 27.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

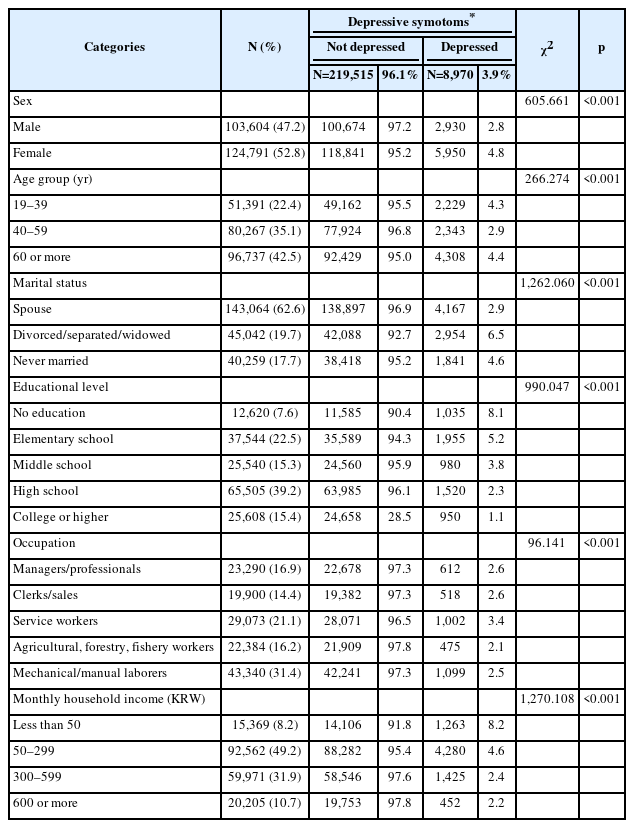

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the study population, including the PHQ-9 score. Of the 228,485 participants, 8,970 (total: 3.9%; male: 2.8%; female: 4.8%) had depressive symptoms. The prevalence of depressive symptoms differed significantly according to age, marital status, educational level, occupation, and monthly household income group (p<0.001) (Table 1).

The interrelations among depressive symptoms, adoption of infection-preventive behaviors, and related factors are presented in Table 2. Compared to the control group, individuals with depressive symptoms were significantly less likely to 1) adopt protective behaviors, such as hand washing, social distancing, and refraining from visiting hospitalized patients and going out, and 2) follow psychological recommendations (p<0.001). Depressive symptoms were significantly associated with lack of concern regarding infection (p=0.002) and concerns about death (p<0.001) as well as blame (p<0.001), and economic damage (p<0.001), but not with concerns about infection of people with poor health (p=0.100). The depressed group appeared to adopt unhealthy lifestyle changes after the outbreak of COVID-19 (p<0.001) and was significantly more likely to think that the response to COVID-19 was inadequate (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Table 3 presents the results of univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. In the univariate logistic regression analysis, preventive behavior and the four related factors exhibited significant differences between the groups with and without depressive symptoms (Table 3). After controlling for sex, age, marital status, educational level, occupation, and monthly household income, individuals with depressive symptoms were more likely to be non-compliant with preventive behavior for COVID-19 infection and had lower frequency of contact with individuals close to them. In addition, among various concerns, lack of concern about death and economic damage was associated with low ORs even after controlling for demographic factors. The association between adopting unhealthy lifestyle habits, negative opinion regarding the adequacy of the response to COVID-19 and depressive symptoms persisted after controlling for demographic variables. Table 3 shows detailed data.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed data from the nationwide KCHS to evaluate the adoption of COVID-19 preventive behaviors and related factors in individuals with depressive symptoms. Individuals with depressive symptoms exhibited lower rates of adoption of protective behaviors against COVID-19, such as frequent hand washing, social distancing, refraining from visiting hospitalized patients, and not going out, than those without depressive symptoms. Individuals with depressive symptoms were less likely to engage in protective behaviors than individuals without depressive symptoms because of their heightened vulnerability. According to one study [23], other-oriented factors, beyond self-oriented factors, were found to be related to protective behavior against COVID-19 infectious disease. Moral judgment and empathy for loved ones were dominant factors, controlling for all aspects. Cognitive changes in depressed patients, such as negative judgments about themselves and the world, affect their moral judgment [24]. Although there is support for the view that the susceptibility to blame in depressed people affects their moral judgment, in this study, concerns about blame were not found to be significant in depressed people; hence, more research is needed. Studies have shown that negative cognitions in depression are associated with low empathy [25], but contrasting views have been noted about the relationship between empathy and depression [26,27]. Furthermore, these findings are supported by studies suggesting that the major lesion sites in the neural circuit model of depression are related to the self-referential function, and that dysfunction within and between important structures in this circuit can induce disturbances in emotional behavior and other cognitive aspects of depressive syndromes in humans [28].

Our study found that lack of contact with people close to them, which is recommended to prevent psychological problems, was correlated with depressive symptoms. The causal relationship between social contact and depressive symptoms is unclear, although a correlation is observed [29,30]. With the pandemic raging stronger, feelings of isolation may intensify, leading to depressive symptoms [29]. However, the prevalence of depression in our study group was found to be 3.9% based on the PHQ-9 cutoff 10 points, which is lower than the 6.7% prevalence noted in the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey before the pandemic [11,31]. Therefore, it is possible that our study included fewer people newly depressed due to COVID-19 and thus may be better suited to examine the adoption of COVID-19 preventive behaviors by individuals with preexisting depressive symptoms.

Concerns regarding COVID-19 infection, including fear of death, blaming others for spreading the virus, and worrying about the negative consequences of infection likely promote the adoption of COVID-19 protective behaviors [32]. In the present study, after controlling for demographic factors, worrying about death, economic damage, and depression were significantly association with the adoption of COVID-19 preventive behaviors, while concerns regarding spread of COVID-19 infection and blaming others were not significant. These are likely symptoms of depression, which is inconsistent with the assumption that various concerns or fears can promote protective behavior and that depression would interfere with protective behavior. Therefore, more studies based on various other symptoms and severity of depression will be needed [33].

In line with a previous study [34], we found depressive symptoms to be strongly associated with unhealthy lifestyle changes. Social isolation and unhealthy lifestyle changes were common challenges faced by individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although depressive symptoms are associated with social isolation, the direction of this relationship is unclear. In other words, it is unknown whether individuals with depressive symptoms have more severe social isolation or whether social isolation leads to depressive symptoms.

As with previous studies, the association of depression with reduced physical activity and sleep problems may be related to disruptions in daily rhythms that occurred during the pandemic [35-39]. Similar to our findings, several other studies have also found that the pandemic led to increased consumption of fast food, which can be a trigger for or worsen symptoms of depression [40-42]. Our findings of an association between depression and increased prevalence of smoking and drinking are consistent with previous studies [29,30], suggesting that, for individuals with depressive symptoms, unhealthy lifestyles may have worsened due to the pandemic [43-45].

In the present study, individuals with depressive symptoms had lower evaluations of the adequacy of the responses of the government, medical institutions, and neighbors to COVID-19. Such attitudes can produce a negative effect on individuals with depression in terms of following rules of quarantine, etc. Trust in government is associated with positive mental health outcomes, including depression and anxiety [46,47]. A recent meta-analysis study reported that government responses to COVID-19 had a positive impact on depression, when strict policies were immediately implemented [48]. Although these studies are focused on the impact of government responses to COVID-19 on the prevalence of depression, our findings are more likely responses of people with depression. This is because the Korean government acted quickly to impose strict measures against the spread of infection and, hence, the prevalence of depression observed from the data used in this study was relatively low, at 3.9%.

Although our study contributes to understanding about adoption of protective behavior toward COVID-19 and related factors in individuals with depression, it has certain limitations. First, the cross-sectional design of the study precluded causal inference. Vulnerability with respect to protective behaviors and related factors may be a consequence of preexisting depression, and our results should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, KCHS included a large population (228,485 people) and is considered representative of the entire Korean population. Future studies using a longitudinal designs may help generate high-quality evidence to determine causality. Additionally, more studies are needed to explore the COVID-19 infection rate and related factors in depressed patients. Second, KCHS was conducted between August and October 2020, almost half a year after the outbreak. As of August 2020, 5,642 individuals had contracted COVID-19 in Korea, representing a lower prevalence rate than in other countries. This could limit the generalizability of our findings. Third, mental health problems related to the adoption of infectious disease-protective behavior include not only depressive symptoms but also anxiety and trauma symptoms [49]. However, the present study included only individuals with depressive symptoms. Furthermore, we did not explore all factors that can potentially affect the adoption of protective behavior. Although confounding factors were added to the multivariate logistic regression analysis to overcome these limitations, additional factors should be evaluated in future studies [50,51].

In conclusion, after the COVID-19 outbreak, individuals with depressive symptoms were less compliant with COVID-19 preventive measures, adopted less healthy lifestyles, and had negative opinions about the appropriateness and adequacy of the response of the government and various institutions to COVID-19. These findings suggest the possibility of increased susceptibility to infection and poor physical and mental health in this population. Therefore, comprehensive management strategies are needed to reduce the infection rate and health risks in individuals with depressive symptoms.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the current study are available in the Korean Community Health Survey repository, https://chs.kdca.go.kr/chs/index.do.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Kyeong-Sook Choi, Ho-Jun Cho. Data curation: Ho-Jun Cho, Jin-Young Lee, Kyeong-Sook Choi. Formal analysis: Ho-Jun Cho, Kyeong-Sook Choi. Funding acquisition: Kyeong-Sook Choi. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: Kyeong-Sook Choi. Resources: Kyeong-Sook Choi. Supervision: Kyeong-Sook Choi. Validation: Kyeong-Sook Choi, Ji-Ae Yun, Je-Chun Yu. Visualization: Ho-Jun Cho, Kyeong-Sook Choi. Writing—original draft: Ho-Jun Cho, Kyeong-Sook Choi. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Research of Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (2021-11-020). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.