|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 21(4); 2024 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

This study was to examine the mediated moderation effect of mindfulness through rumination on the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction. In particular, this study examined the moderating effect of mindfulness in detail by dividing it into five sub-factors.

Methods

An online self-report questionnaires were conducted on 697 participants aged 20 to 59. Finally, 681 participants (male=356, female=325) were included final analysis. Moderating effect, mediated moderating effect were verified using PROCESS macro for SPSS v3.5.

Results

First, perceived stress was positively related to smartphone addiction. Second, rumination mediated the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction. Third, acting with awareness and nonjudging of experience, which are a sub-factor of mindfulness, moderated the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction. Fourth, mindfulness facets (acting with awareness and nonjudging of experience) moderated the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction. Finally, there was a mediated moderating effect of mindfulness facets (acting with awareness and nonjudging of experience) on the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction through rumination.

According to the smartphone addiction survey conducted by National Information Society Agency [1], the percentage of smartphone addiction risk group in 2021 was 24.2 and has been continuously increasing since the survey started in 2013. In particular, in the case of adults between the ages of 20 and 60, although the percentage of the risk group for smartphone addiction is at 23.3% as of 2021, the problem of smartphone addiction in adults is overlooked compared to adolescents [2-5].

The term smartphone addiction should be used carefully because it can cause negative stigma and passive participation in treatment [6]. Nevertheless, the term addiction has been used worldwide, and this study also intends to use the term addiction on smartphones. Smartphone addiction is defined as excessive use of smartphones despite poor autonomous control of smartphones, more important activities than other daily activities in individual lives, and negative results in physical, emotional, and social areas [7,8].

Depression, anxiety, self-regulation ability, loneliness, and stress have been suggested as individual psychological factors that can cause smartphone addiction [5,9-11]. In particular, stress has been pointed out as a strong risk factor for smartphone addiction [5,12,13]. According to the Tension Reduction Theory of Conger [14], when an individual continuously perceives stress in daily life and the tension is maintained, he experiences negative emotions, and can use overuse smartphone to relieve the tension. The tension reduction theory has been applied to studies related to alcohol or Internet addiction, and it can also be applied to the smartphone addiction [15-17].

Davis [18] described the process leading to media addiction based on the cognitive-behavioral model. The cognitive-behavioral model helped to understand the psychological mechanism of addiction and to provide therapeutic intervention methods [19]. Davis [18] divided the factors affecting addiction into distal contributory and proximal contributory causes. Distal causes include a predisposed vulnerability and stressful events. However, it is hypothesized that distal causes have a stronger effect on smartphone addiction when mediated by the process of proximal causes. Davis [18] observed that the core of the addiction process is the cognitive dimension, which is the proximal causes, and maladaptive cognition is viewed as a major variable leading to smartphone addiction. Maladaptive cognitions consist of two main subtypes: thoughts about the self, and thoughts about the world. In particular, thoughts about the self is derived from the rumination cognitive style, and individuals with severe rumination tend to persistently and pathologically use smartphones [18,20].

Rumination is defined as a maladaptive cognitive style that repeatedly focuses on the meaning or causes and consequences of negative emotions and individual problems [21,22]. An individualŌĆÖs perceived external stress is closely related to rumination [23]. According to previous studies, rumination induced by stressful events has invasive and immersive cognitive characteristics, leading to immersion in specific behaviors to escape negative and repetitive thoughts, and may lead to smartphone addiction [5,24,25]. In fact, it was found that rumination is an important predictor of smartphone overuse, Internet dependence, and online game addiction [26-31]. That is, based on DavisŌĆÖs [18] cognitive-behavior model and empirical research, perceived stress can not only directly relate to smartphone addiction, but also in relation to smartphone addiction by mediating rumination.

For effective therapeutic intervention for smartphone addiction, it is necessary to pay attention to cognitive characteristics that are relatively likely to change [32]. According to previous studies, cognitive behavioral therapy helps identify maladaptive cognition [33,34]. In particular, mindfulness has recently attracted attention as a protective factor for behavioral addiction, as it has been found to be effective in behavioral regulation by deliberately paying attention to oneŌĆÖs own cognitive processes [35-38]. Mindfulness is defined as intentionally paying attention to the present moment to accept the senses, emotions, and thoughts that occur within oneself as they are, and to recognize and accept them non-judgmentally [36]. Attention, awareness, and receptive attitude toward perceived experience, a key mechanism of mindfulness, can change the inner response pattern to problem situations and increase cognitive flexibility, which can be effective in reducing ruminative response patterns and preventing problem behavior in stress situations [39,40]. Previous studies have shown that mindfulness can be effective in reducing rumination and preventing problem behavior because it converts attention that was focused only on oneself in stressful situations into various external information. For example, mindfulness based cognitive therapy assumes that it can efficiently manage negative emotions and suppress ruminative thinking by recognizing the ruminative cognitive process that automatically takes place in stressful situations [41-43]. However, the specific psychological mechanism how mindfulness reduces smartphone addiction has not been sufficiently verified [41,44].

A study conducted on college students showed that the moderating effect of mindfulness was significant in the relationship between stress on smartphone addiction [45]. And, a study of middle school students, the moderating effect of mindfulness was significant in the relationship between test anxiety and smartphone addiction [46]. In a study by Son [11], moderating effect of mindfulness was found in the pathway where stress mediated anxiety and affects addiction behaviors such as alcohol, drugs, gambling, and games. Specifically, the group with high level of mindfulness had a lower level of addiction than the group with low level of mindfulness, even though stress-induced anxiety increased.

Recent researchers have suggested that there are individual differences in the level of mindfulness even in those who have not experienced mindfulness-based therapy and meditation, and have suggested sub-factors of mindfulness [47]. Representatively, Baer et al. [48] proposed five sub-factors: nonreactivity, observation, acting with awareness, describing, and nonjudging experience. Specifically, nonreactivity is not overwhelmed by inner experiences and does not respond immediately. Observation is to pay attention to, recognize, and observe various stimuli such as internal phenomena such as body sensations, cognition, and emotions and external phenomena such as smell. Acting with awareness is to participate in oneŌĆÖs present activities without distracting others. Describing is to verbalize and describe and name observed phenomena. Nonjudging does not judge good/bad, right/wrong, etc [49]. Since mindfulness is a multidimensional concept composed of various factors, detailed therapeutic intervention in smartphone addiction will be possible only by looking at each sub-factor. However, most studies only examined the overall level using the total score of mindfulness scale, limiting the understanding of which factors of mindfulness affect problem behavior [48,50,51].

Although it has been confirmed through previous studies that mindfulness alleviates stress, rumination, and behavioral addiction [52-54], there are few studies have examined the relationship between the sub-factors of mindfulness and addiction. Park and Chung [55] study showed that higher nonreactivity and acting with awareness was positively related to regulation of specific behaviors. In the study of Park [56], the other factors except for describing factors had a significant relation to stress mitigation. In overseas studies, describing and nonjudging had related to relieving stress levels [57]. In the study of Eisenlohr-Moul et al. [58] the higher the level of observation and nonreactivity, the lower the level of addiction. Bowen and Enkema [35] found that higher acting with awareness, nonjudging and describing were associated with lower addiction severity. As such, the results of the study on the relationship between the sub-factors of mindfulness and addiction were somewhat mixed [51,56,58-60]. These results may be due to the fact that only some aspects of mindfulness were considered in previous studies [61-63].

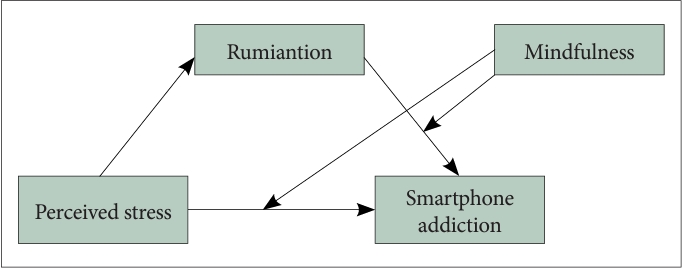

Therefore, based on DavisŌĆÖs cognitive-behavioral model, this study aims to identify the specific path through which perceived stress leads to smartphone addiction through rumination. In particular, this study aims to verify the moderating effect of each sub-factor of mindfulness in the path of stress on smartphone addiction through rumination, and to confirm the mediated moderating effect by integrating it. This study is based on the following hypotheses: First, there will be a mediating effect of rumination in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction. Second, mindfulness will moderate the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction. Third, mindfulness will moderate the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction. Fourth, in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction, the mediated moderating effect of mindfulness through rumination will be significant. The research model to be verified in this study is presented in Figure 1.

This study was conducted after obtaining approval from Dankook UniversityŌĆÖs Institutional Review Board (approval number: 2021-11-033-004). This study conducted randomly survey of 20 to 59 years old, defined as adults in Korea, using an online self-report questionnaire (the Google questionnaire form) distributed on the online site, and obtained the consent of each participant. We recruited 697 adults, and offered them with a prescribed mobile gift card. For unreliable data on some vital study variables, 16 people who did not answer more than 30% of the questions had to be excluded.

Looking at the general characteristics of the participants, 356 male (52.3%), 325 female (47.7%), and the average age was 37.78 years (standard deviation [SD]=10.37). There were 188 (27.6%) in their 20s, 190 (27.9%) in their 30s, 179 (26.3%) in their 40s, and 124 (18.2%) in their 50s. The classification according to the smartphone addiction group was 418 (61.4%) in the general user group, 165 (24.2%) in the potential risk group, and 98 (14.4%) in the high-risk group. The potential risk and high-risk groups are grouped and defined as smartphone addiction groups.

To measure perceived stress, a scale developed by Cohen and Williamson [64], and translated into Korean and validated by Park and Seo [65] was used. This Perceived Stress Scale consists of 10 items, and each item is rated on a 5-points Likert scale (1 point=not at all, 5 points=very much). The higher the score, the higher the perceived stress level. CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ in this study was 0.76.

Ruminative response was measured using Ruminative Response Scale developed by Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow [22], and translated into Korean and validated by Kim et al. [66]. This scale consists of two subscales; brooding and reflection, with 10 items, and is rated on 4-point Likert scale (1=almost never, 4=almost always). In this study, only a 5-item rumination subscale was used based on previous research [67]. CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ in this study was 0.68.

Mindfulness was measured using the Korean Five-factor Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ), originally developed by Baer et al. [48] and translated into Korean and validated by Won and Kim [49]. Originally, this scale consisted of a total of 39 items on a 7-point Likert scale, but in this study, a 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 5=always) was reconstructed and used. The higher the score, the higher the tendency to be mindful in daily life. The sub-factors consist of nonreactivity, observing, acting with awareness, describing, and nonjudging of experience. In this study, CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ was 0.76, and CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ of each subscale was in the range of 0.65-0.79.

To measure smartphone addiction, the smartphone addiction integration scale developed by the National Information Society Agency in 2016 was used [68]. The scale was developed by integrating the Internet overdependence scale (K-scale) developed and standardized in 2002 and the smartphone overdependence scale (S-scale) developed and standardized in 2011. The smartphone addiction integration scale consists of three sub-factors: self-control failure, salience, and serious consequences. This scale has a total of 10 items and is rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1=disagree completely, 4=agree completely), with a total score of 40 points; a higher score indicates a higher level of smartphone addiction. It is classified into three groups: high-risk group, potential risk group, and general user group. Among them, high-risk groups and potential risk groups are classified into smartphone addiction risk groups. Adults between the ages of 20 and 59 are classified as high-risk groups if the total score is 29 or higher, potential risk groups if the total score is 24 or higher and 28 or lower, and general users if the total score is 23 or lower. The CronbachŌĆÖs ╬▒ was 0.83.

The data collected in this study were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and PROCESS macro for SPSS version 3.5 developed by Hayes [69]. The mediating effect was analyzed using PROCESS macro model 4, and to verify the statistical significance of the mediating effect, 5,000 samples were extracted using bootstrapping and the statistical significance of the indirect effect was verified at the 95% confidence interval (CI). The PROCESS macro model 1 was used to examine moderating effect by mean-centering the independent variable and the moderating variable to minimize the problem of multicollinearity [69]. In addition, simple regression test was conducted to verify the significance of the moderating variable at three levels (mean -1SD, mean, mean +1SD) according to Aiken et al. [70]. Finally, PROCESS macro model 15 was used to verify the mediated moderating effect of mindfulness on the relationship between perceived stress, rumination, and smartphone addiction. Since the mediated moderating model is a combination of the mediating model and the moderating model, it can be analyzed when both the simple mediating effect and the simple moderating effect constituting each model are significant [71].

In this study, the mean, SD, and each correlation of the major variables are shown in Table 1. As a result of correlation analysis, perceived stress showed a significant positive correlation with rumination (r=0.454, p<0.01) and smartphone addiction (r=0.343, p<0.01). Also, mindfulness was negatively correlated with perceived stress (r=-0.479, p< 0.01), rumination (r=-0.369, p<0.01), and smartphone addiction (r=-0.344, p<0.001). That is, high levels of mindfulness are associated with low levels of perceived stress, rumination and mindfulness.

In order to verify whether rumination mediates the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction, bootstrapping was performed using SPSS PROCESS macro model 4. 5,000 samples were resampled and analyzed by bootstrapping, and the indirect effect coefficient was 0.209. Also, in the 95% CI, the lower and upper limits of rumination were 0.150 and 0.275, respectively, so 0 was not included in the bootstrap CI, so the mediating effect of rumination was significant [72].

To verify the moderating effect of the sub-factors of mindfulness (nonreactivity, observing, acting with awareness, describing, and nonjudging), the SPSS ROCESS macro model 1 was used. In order to minimize the problem of multicollinearity, the independent variable and the sub-factors of moderating variable mindfulness were analyzed after mean-centering [69].

Perceived stress (B=0.468, t=9.983, p<0.001) and nonreactivity (B=0.232, t=3.876, p<0.001) were positively related to smartphone addiction. However, the interaction effect of two variables on smartphone addiction was not significant. Perceived stress (B=0.407, t=9.051, p<0.001) and observing (B= 0.136, t=3.216, p<0.01) were positively related to smartphone addiction, but the interaction effect of two variables on smartphone addiction was not significant. Perceived stress (B=0.207, t=4.609, p<0.001) and acting with awareness (B=-0.490, t= -12.824, p<0.001) were found to have a significant relation to smartphone addiction. In addition, the interaction effects of the two variables (B=-0.013, t=-2.175, p<0.05) was also affect smartphone addiction. Looking at the moderating effect of the describing, perceived stress (B=0.408, t=8.562, p<0.001) was positively related to smartphone addiction, but the interaction effect between perceived stress and describing was not significant. Perceived stress (B=0.368, t=8.133, p<0.001) and nonjudging (B=-0.252, t=-6.349, p<0.001) were found to have a significant relation to smartphone addiction. In addition, the interaction effect of the two variables (B=-0.019, t=-3.044, p<0.05) was also affect smartphone addiction. The results are presented in Table 2.

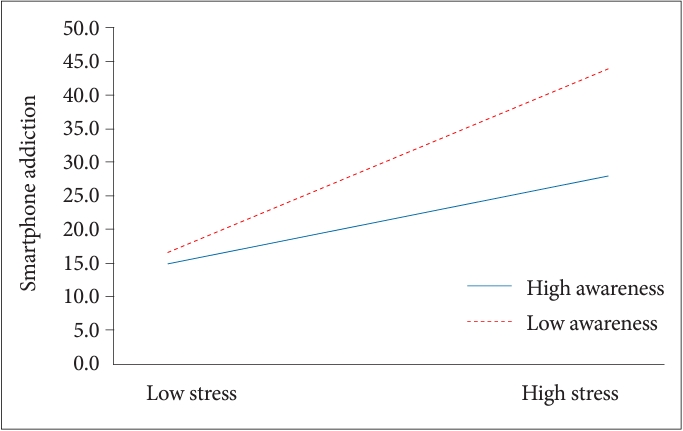

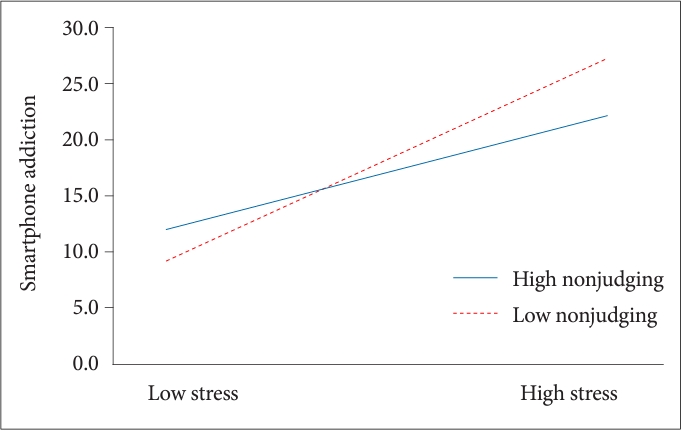

As the interaction effect between the acting with awareness and the nonjudging was significant, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable in the conditional values of the moderating variables (mean -1SD, mean, mean+1SD) was analyzed (Table 3). The effect of perceived stress on smartphone addiction decreased in the group with a high level of acting with awareness compared to other groups. The nonjudging also showed a similar tendency (Figures 2 and 3).

Looking at the moderating effect of nonreactivity, rumination (B=0.854, t=12.560, p<0.001) was positively related to smartphone addiction, but the interaction effect between rumination and nonreactivity was not significant. Rumination (B=0.810, t=11.819, p<0.001) was positively related to smartphone addiction, but the interaction effect of rumination and observing was not significant. Rumination (B=0.515, t=7.697, p<0.001) and acting with awareness (B=-0.431, t=-11.753, p< 0.001) were found to have a significant relation to smartphone addiction. In addition, the interaction effects of the two variables (B=-0.033, t=-3.576, p<0.001) was also affect smartphone addiction. Rumination (B=0.848, t=12.530, p<0.001) and describing (B=-0.120, t=-2.677, p<0.01) were found to have a significant relation to smartphone addiction, but the interaction effect of rumination and describing on smartphone addiction was not significant. Rumination (B=0.733, t=9.649, p<0.001) and nonjudging (B=-0.129, t=-3.045, p<0.01) were found to have a significant relation to smartphone addiction. In addition, the interaction effect of the two variables (B=-0.026, t=-2.490, p<0.05) was also affect smartphone addiction. The results are presented in Table 4.

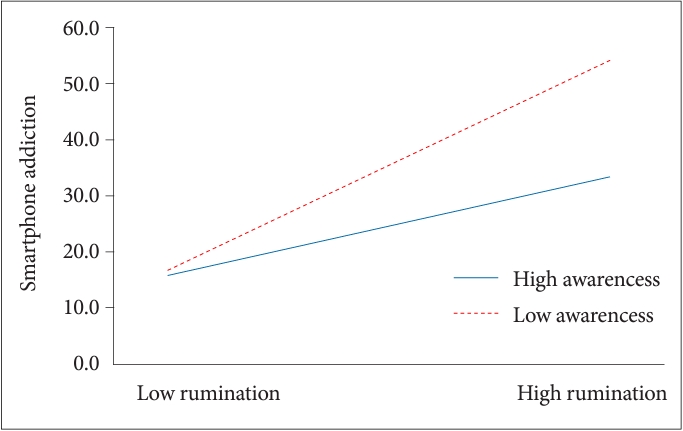

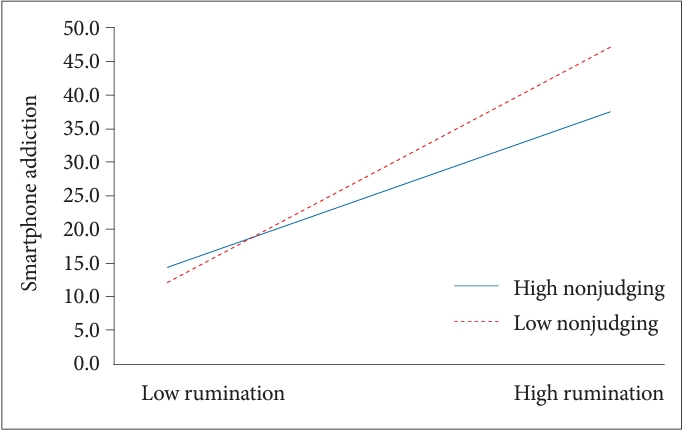

As the interaction effect between the acting with awareness and the nonjudging was significant, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable in the conditional values of the moderating variables (mean -1SD, mean, mean+ 1SD) was analyzed (Table 5). The effect of rumination on smartphone addiction decreased in the group with a high level of acting with awareness compared to other groups. The nonjudging also showed a similar tendency (Figures 4 and 5).

The verification of the mediated moderating effect was confirmed according to the integrated model and stepwise approach proposed by Muller et al. [73]. After verifying the hypothesis according to the research model, the mediated moderating effect was verified using the SPSS PROCESS macro model 15 to confirm the conditional indirect effect using the bootstrapping proposed by Preacher et al. [71].

In the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction, the moderating effect of acting with awareness was significant (B=-0.013, t=-2.175, p<0.05), and the main effect of perceived stress on rumination was significant (B=0.232, t=9.944, p<0.001), and the moderating effect of acting with awareness was significant in the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction (B=-0.037, t=-3.462, p<0.01). Finally, in order to confirm the verification of the mediated moderating effect, the significance of the interaction term of acting with awareness in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction was examined. As a result, the direct moderation effect was no longer significant, which means that the fully mediated moderating effect was finally verified.

Next, the coefficient values and statistical significance of the mediated moderating effect were confirmed using bootstrapping (Table 6). As a result of the analysis, the indirect effect of mediated moderating effect decreased as the level of acting with awareness increased (mean -1SD=0.194, mean=0.134, mean +1SD=0.074).

In the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction, the moderating effect of nonjudging was significant (B=-0.019, t=-3.044, p<0.01), and the main effect of perceived stress on rumination was significant (B=0.230, t=11.112, p<0.001), and the moderating effect of nonjudging was significant in the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction (B=-0.024, t=-1.998, p<0.05). Finally, in order to confirm the verification of the mediated moderating effect, the significance of the interaction term of nonjudging in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction was examined. As a result, the direct moderation effect was no longer significant, which means that the fully mediated moderating effect was finally verified.

Next, the coefficient values and statistical significance of the mediated moderating effect were confirmed using bootstrapping (Table 7). As a result of the analysis, the indirect effect of mediated moderating effect decreased as the level of nonjudging increased (mean -1SD=0.204, mean=0.166, mean +1SD=0.129).

This study aims to examine the moderating effect of subfactors of mindfulness in the path of stress on smartphone addiction through rumination, and to verify the mediated moderating effect by integrating it. The comprehensive discussion of the main results of this study is as follows.

First, perceived stress had a positive effect on smartphone addiction. This result supports the previous studies reporting stress as a predictor of smartphone addiction [74,75]. Smartphones can be easily used regardless of time and place, and can be used to avoid stress situations [76]. These results suggest that adults who perceive various stresses use smartphones as a coping means to escape from stress, which may lead to smartphone addiction [77,78].

Second, the partial mediating effect of rumination was significant in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction [79,80]. DavisŌĆÖs [18] cognitive-behavioral model argued that the core of pathological media use is maladaptive cognition. It is also characterized by focusing on the cognitive process of media addiction by revealing not only the content of maladaptive cognition but also the process of maladaptive cognition. Davis [18] argues that individual psychological and environmental factors work in a complex to induce rumination in stressful situations. Because an individualŌĆÖs behavior occurs through interaction with the external environment and the individualŌĆÖs emotions and cognitions, emphasizing only one aspect is insufficient to explain smartphone addiction [18,30]. When a personŌĆÖs vulnerability interacts with a stressor, the person becomes immersed in the use of a smartphone to escape a stressful situation. However, stress does not directly cause smartphone addiction, but is caused by strengthening maladaptive cognition in stressful situations. It is in line with previous studies that individuals may become smartphone addiction to alleviate heightened anxiety due to repeated rumination about perceived stress [11,81].

Third, in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction, the moderating effects of acting with awareness and nonjudging, which are sub-factors of mindfulness, were found to be significant. This is in line with the fact that when the level of acting with awareness and nonjudging is high, emotional stimuli can be distanced from stressful situations, and negative stimuli are evaluated less negatively [51,56,82]. In a study of adults [83], Acting with awareness and nonjudging showed negatively correlation with addiction. When an individual perceives stress, if the level of acting with awareness and nonjudging is high, negative emotions can be alleviated by fully accepting external stimuli, which can prevent addiction.

Fourth, in the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction, the moderating effect of acting with awareness and nonjudging was found. This results support previous studies that show that individuals with high levels of acting with awareness and nonjudging can be fully aware of their inner experiences when experiencing negative events, resulting in lower levels of rumination [84,85]. Smartphone addiction is caused by a failure of self-regulation, and efforts to recognize and effectively deal with maladaptive cognition are required to solve this problem. In particular, acting with awareness and nonjudging play an important role in effectively dealing with maladaptive cognition because they pay attention to the current experience non-judgmentally [34,84].

Finally, there was a significant mediated moderating effect mediated by rumination in the interaction effect of perceived stress and acting with awareness and nonjudging. It can be seen that the interaction of perceived stress, acting with awareness, and nonjudging changes the influence of rumination, and the changed level of rumination affects smartphone addiction. Mindfulness requires a higher cognitive skill that can observe the motivation, intention, and process of noticing to pay attention to the current experience [33]. In particular, acting with awareness and nonjudging allows us to consciously look at the automatic process of smartphone use and explore and accept maladaptive perceptions that cause smartphone addiction [34].

On the other hand, it was found that sub-factors of mindfulness (nonreactivity, observing, and describing) did not have a significant moderating effect in all pathways [51]. The results of this study can also be seen as a phenomenon that occurs when targeting ordinary people who have no meditation experience. In past studies of people with meditation experience, there was a high correlation between the sub-factors of mindfulness, but in a study of people with little or no meditation experience, the correlation between the sub-factors was not high, and there was no significant correlation between the sub-factors [48,49,51,86]. These results of this study may be due to the fact that the study was conducted on ordinary people without controlling the meditation experience.

The main contribution of this study was to clarified the mechanism of smartphone addiction. In previous domestic and foreign studies, it was not clear whether the cognitive-behavior model could effectively explain the development path of smartphone addiction, although the specific mechanism to Internet addiction was confirmed by applying cognitive behavior models [18,20,33,87]. Second, previous studies have revealed the effectiveness of mindfulness intervention programs for college students at risk of smartphone addiction, but have not specifically confirmed how mindfulness relieves smartphone addiction [38]. This study examined the role of mindfulness in the process that perceived stress mediates rumination and leads to smartphone addiction. Third, this study specifically examined the moderating effect of mindfulness by dividing it into five sub-factors. Among the sub-factors of mindfulness, only acting with awareness and nonjudging showed significant moderating effects in each of the perceived stress and rumination, rumination and smartphone addiction pathways. The results of this study are consistent with the argument of Shapiro et al. [88], who explain that acting with awareness and nonjudging are the main mechanisms of mindfulness. This means that the higher the level of self-awareness and nonjudging, the farther away from the maladaptive cognition experienced in stress situations, and the less evasive and addictive behavior due to the receptive attitude to stimuli. Through clinical intervention based on this theory, smartphone addiction can be alleviated.

The limitations of this study and suggestions are as follows. First, there are limitations in the psychometric properties or validity of the Korean version of the FFMQ used in this study. The correlation between acting with awareness and nonreactivity was not significant in this study, which is coincides with the fact nonreactivity had a smaller explanation compared to other factors in the Korean version of the five-factor validation study [49]. In addition, in studies using this scale for the general public in Korea, the correlation between factors were also found to be different [49,51,56,89,90]. Since this scale can interpret items differently depending on the individualŌĆÖs meditation experience, it is necessary to identify and control variables that can affect the interpretation and response of the items, such as the individualŌĆÖs meditation experience or temperament aspect. Second, all of the data in this study were collected through self-reporting surveys. Since self-reporting surveys have the possibility of social desirability, there may be differences in research results depending on individual reactivity, and the possibility that they did not respond honestly cannot be ruled out. Third, since this study was conducted through cross-sectional design, there is a limit to grasping the causal relationship between variables. Finally, this study did not use type of instrument (i.e., Smartphone Application Based Addiction Scale) that has been validated across countries and that future studies are hard to replicate the present findings because the currently used instrument assessing smartphone addiction in the present study is not well-known across countries [8,91].

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ji-Hyeon Jeong, Sung Man Bae. Data curation: Ji-Hyeon Jeong, Sung Man Bae. Formal analysis: Ji-Hyeon Jeong. Investigation: Ji-Hyeon Jeong. Methodology: Ji-Hyeon Jeong, Sung Man Bae. Project administration: Ji-Hyeon Jeong, Sung Man Bae. Supervision: Sung Man Bae. Validation: Ji-Hyeon Jeong. Visualization: Ji-Hyeon Jeong. WritingŌĆöoriginal draft: Ji Hyeon Jeong. WritingŌĆöreview & editing: Sung Man Bae.

Funding Statement

None

Figure┬Ā1.

A research model on the mediating moderating effect of mindfulness in the relationship between perceived stress, ruminant, and smartphone addiction.

Figure┬Ā2.

The moderating effect of acting with awareness in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction.

Figure┬Ā3.

The moderating effect of nonjudging in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction.

Figure┬Ā4.

The moderating effect of acting with awareness in the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction.

Figure┬Ā5.

The moderating effect of nonjudging in the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction.

Table┬Ā1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations of variables (N=681)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||||

| 2 | 0.454** | ||||||||

| 3 | -0.479** | -0.369** | |||||||

| 4 | -0.284** | -0.046 | 0.492** | ||||||

| 5 | 0.004 | 0.178*** | 0.393** | 0.448** | |||||

| 6 | -0.419** | -0.427** | 0.635** | 0.013 | -0.189** | ||||

| 7 | -0.301** | -0.124** | 0.700** | 0.321** | 0.299** | 0.232** | |||

| 8 | -0.277** | -0.478** | 0.462** | -0.200** | -0.349** | 0.473** | 0.102** | ||

| 9 | 0.343** | 0.452** | -0.344*** | 0.039 | 0.127** | -0.530** | -0.242** | -0.310** | |

| M | 29.09 | 12.43 | 118.49 | 19.11 | 24.76 | 24.91 | 25.75 | 23.96 | 22.09 |

| SD | 4.89 | 3.10 | 13.21 | 3.75 | 5.10 | 5.63 | 4.65 | 5.49 | 6.02 |

| W | -0.38 | 0.06 | 0.58 | -0.02 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.06 | 0.13 |

| K | 0.67 | -0.53 | 2.80 | 0.05 | -0.27 | -0.12 | 0.72 | 0.29 | -0.09 |

Table┬Ā2.

The moderating effect of mindfulness in the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction (N=681)

| Variables | B | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI | F | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived stress | 0.468 | 0.047 | 9.983*** | 0.376 | 0.559 | ||

| Nonreactivity | 0.232 | 0.060 | 3.876*** | 0.115 | 0.350 | 28.878*** | 0.146 |

| Perceived stress├Śnonreactivity | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.389 | -0.015 | 0.022 | ||

| Perceived stress | 0.407 | 0.045 | 9.051*** | 0.318 | 0.495 | ||

| Observation | 0.136 | 0.042 | 3.216** | 0.053 | 0.220 | 27.977*** | 0.142 |

| Perceived stress├Śobservation | 0.010 | 0.007 | 1.412 | -0.004 | 0.024 | ||

| Perceived stress | 0.207 | 0.045 | 4.609*** | 0.119 | 0.295 | ||

| Acting with awareness | -0.490 | 0.038 | -12.824*** | -0.565 | -0.415 | 73.869*** | 0.304 |

| Perceived stress├Śacting with awareness | -0.013 | 0.006 | -2.175* | -0.025 | -0.001 | ||

| Perceived stress | 0.408 | 0.048 | 8.562*** | 0.314 | 0.501 | ||

| Describing | -0.068 | 0.049 | -1.379 | -0.164 | 0.029 | 24.999*** | 0.129 |

| Perceived stress├Śdescribing | -0.004 | 0.007 | -0.564 | -0.019 | 0.010 | ||

| Perceived stress | 0.368 | 0.045 | 8.133*** | 0.279 | 0.457 | ||

| Nonjudging | -0.252 | 0.040 | -6.349*** | -0.330 | -0.174 | 38.472*** | 0.185 |

| Perceived stress├Śnonjudging | -0.019 | 0.005 | -3.044* | -0.032 | -0.007 |

Table┬Ā3.

Moderated results for engagement across levels of mindfulness (N=681)

| Moderating variables | Levels | Effect | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acting with awareness | Mean -1SD | 0.281 | 0.063 | 4.485*** | 0.158 | 0.404 |

| Mean | 0.207 | 0.045 | 4.609*** | 0.119 | 0.295 | |

| Mean +1SD | 0.133 | 0.049 | 2.710** | 0.037 | 0.230 | |

| Nonjudging | Mean -1SD | 0.474 | 0.062 | 7.654*** | 0.352 | 0.595 |

| Mean | 0.368 | 0.045 | 8.133*** | 0.279 | 0.457 | |

| Mean +1SD | 0.263 | 0.052 | 5.083*** | 0.161 | 0.364 |

Table┬Ā4.

The moderating effect of mindfulness in the relationship between rumination and smartphone addiction (N=681)

| Variables | B | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI | F | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumination | 0.854 | 0.068 | 12.560*** | 0.720 | 0.987 | ||

| Nonreactivity | 0.074 | 0.056 | 1.326 | -0.036 | 0.184 | 45.869*** | 0.213 |

| Rumination├Śnonreactivity | 0.027 | 0.015 | 1.798 | -0.002 | 0.056 | ||

| Rumination | 0.810 | 0.068 | 11.819*** | 0.675 | 0.944 | ||

| Observation | 0.038 | 0.041 | 0.929 | -0.042 | 0.119 | 48.580*** | 0.223 |

| Rumination├Śobservation | 0.010 | 0.007 | 3.628 | 0.019 | 0.064 | ||

| Rumination | 0.515 | 0.067 | 7.697*** | 0.383 | 0.646 | ||

| Acting with awareness | -0.431 | 0.037 | -11.753*** | -0.503 | -0.359 | 93.103*** | 0.355 |

| Rumination├Śacting with awareness | -0.033 | 0.009 | -3.576*** | -0.051 | -0.015 | ||

| Rumination | 0.848 | 0.068 | 12.530*** | 0.715 | 0.981 | ||

| Describing | -0.120 | 0.045 | -2.677** | -0.207 | -0.032 | 46.206*** | 0.215 |

| Rumination├Śdescribing | -0.006 | 0.013 | -0.485 | -0.032 | 0.019 | ||

| Rumination | 0.733 | 0.076 | 9.649*** | 0.584 | 0.882 | ||

| Nonjudging | -0.129 | 0.042 | -3.045** | -0.212 | -0.046 | 49.023*** | 0.225 |

| Rumination├Śnonjudging | -0.026 | 0.011 | -2.490* | -0.047 | -0.006 |

Table┬Ā5.

Moderated results for engagement across levels of mindfulness (N=681)

| Moderating variables | Levels | Effect | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acting with awareness | Mean -1SD | 0.702 | 0.081 | 8.659*** | 0.543 | 0.861 |

| Mean | 0.515 | 0.067 | 7.697*** | 0.383 | 0.646 | |

| Mean +1SD | 0.328 | 0.089 | 3.703*** | 0.154 | 0.502 | |

| Nonjudging | Mean -1SD | 0.878 | 0.090 | 9.750*** | 0.701 | 1.055 |

| Mean | 0.733 | 0.076 | 9.649*** | 0.584 | 0.882 | |

| Mean +1SD | 0.588 | 0.101 | 5.825*** | 0.390 | 0.787 |

Table┬Ā6.

Mediated moderation results for engagement across levels of acting with awareness (N=681)

| Moderating variable | Levels | Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acting with awareness | Mean -1SD | 0.194 | 0.039 | 0.122 | 0.276 |

| Mean | 0.134 | 0.027 | 0.086 | 0.189 | |

| Mean +1SD | 0.074 | 0.032 | 0.012 | 0.139 |

REFERENCES

1. National Information Society Agency. The survey on smartphone overdependence 2021 [Internet]. Available at: https://www.nia.or.kr/site/nia_kor/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=65914&bcIdx=24288&parentSeq=24288. Accessed May 28, 2022.

2. Lee Y, Lee E. Communication competence and self-esteem on the relationship between military service stress and smartphone overdependence of Republic of Korea navy soldiers. Korean J Youth Stud 2020;27:27-52.

3. Jeong GC, Cho MG. Relationship between stress and internet ┬Ę smartphone addiction: mediating effects of learned helplessness and procrastination. J Korea Contents Assoc 2017;17:175-185.

4. Lee HJ, Lim JS. Influence of social isolation on smart phone addiction through self-regulation and social support. J Korea Contents Assoc 2019;19:482-498.

5. Lim J. Mediating effect of maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies and negative affect on the relationship between perceived stress and smartphone addiction. J Korea Contents Assoc 2018;18:185-196.

6. Zwick J, Appleseth H, Arndt S. Stigma: how it affects the substance use disorder patient. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy 2020;15:50

7. Bae SM. The relationship between the type of smartphone use and smartphone dependence of Korean adolescents: national survey study. Child Youth Serv Rev 2017;81:207-211.

8. Csibi S, Griffiths MD, Cook B, Demetrovics Z, Szabo A. The psychometric properties of the smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABAS). Int J Ment Health Addict 2018;16:393-403.

9. Choi D, Lee H. The mediating effects of emotion regulation difficulties on the relationship between loneliness and smartphone addiction. Cogn Behav Ther Korea 2017;17:87-103.

10. Matar Boumosleh J, Jaalouk D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students- A cross sectional study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182239.

11. Son J. The effects of stress and anxiety on college studentsŌĆÖ addiction problem: focused on the moderated mediating effects of mindfulness. J Welf Correct 2018;56:29-51.

12. Vahedi Z, Saiphoo A. The association between smartphone use, stress, and anxiety: a meta-analytic review. Stress Health 2018;34:347-358.

13. Zhao P, Lapierre MA. Stress, dependency, and depression: an examination of the reinforcement effects of problematic smartphone use on perceived stress and later depression. Cyberpsychology (Brno) 2020;14:3

14. Conger JJ. Alcoholism: theory, problem and challenge. II. Reinforcement theory and the dynamics of alcoholism. Q J Stud Alcohol 1956;17:296-305.

15. Campbell AJ, Cumming SR, Hughes I. Internet use by the socially fearful: addiction or therapy? Cyberpsychol Behav 2006;9:69-81.

16. Corbin WR, Waddell JT, Ladensack A, Scott C. I drink alone: mechanisms of risk for alcohol problems in solitary drinkers. Addict Behav 2020;102:106147

17. Sung J. The effects of the stresses on smart phone addiction of university students: moderating effects of social support and self esteem. Ment Health Soc Work 2014;42:5-32.

18. Davis RA. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Comput Hum Behav 2001;17:187-195.

19. Caplan SE. Problematic internet use and psychosocial well-being: development of a theory-based cognitive-behavioral measurement instrument. Comput Hum Behav 2002;18:553-575.

20. Ha J. The mediator effect of metacognition on the relationship of perceived stress, anxiety, and problematic internet use [dissertation]. Ewha Womans University. 2011.

21. Martin LL, Tesser A. Some ruminative thoughts. In: Wyer RS, editor. Ruminative thoughts. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1996, p. 1-47.

22. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol 1991;61:115-121.

23. Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cogn Ther Res 2003;27:247-259.

24. Lee EJ. The relations between covert narcissism and addiction tendency to SNS: mediating effect of cognitive emotion regulation strategy [dissertation] Asan, Soonchunhyang University. 2015.

25. Park M, Jeong GC. Influence of perceived stress on quality of sleep in adolescents: mediating effects of rumination and smartphone overdependence. J Wellness 2021;16:216-222.

26. Billieux J, Philippot P, Schmid C, Maurage P, De Mol J, Van der Linden M. Is dysfunctional use of the mobile phone a behavioural addiction? Confronting symptom-based versus process-based approaches. Clin Psychol Psychother 2015;22:460-468.

27. Elhai JD, Tiamiyu M, Weeks J. Depression and social anxiety in relation to problematic smartphone use: the prominent role of rumination. Internet Res 2018;28:315-332.

28. Ha SH. The mediating effects of rumination and mindfulness in the relationship between adolescentŌĆÖs depression and smartphone overdependence [dissertation] Busan, Silla University. 2020.

29. McNicol ML, Thorsteinsson EB. Internet addiction, psychological distress, and coping responses among adolescents and adults. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2017;20:296-304.

30. Park JY. The effect of life stress on smartphone addiction tendency in university students: mediation effects of cognitive emotion regulation strategies [dissertation] Seoul, Dongduk WomenŌĆÖs University. 2018.

31. Shin SI. The influence of parent attachment on smart phone addiction: mediating effects of adaptive emotion regulation and maladaptive emotion regulation. Korean J Youth Stud 2017;24:131-154.

32. Kwon SJ, Im SH, Kim YH. Adolescents game related belief and gaming addiction revisited: a test of position of game related belief using latent growth curve modeling. Kor J Psychol Health 2015;20:267-283.

33. Kim SJ, Kim KH. Cognitive approach to internet addiction improvement: focused on solustion of craving and loss of control. Kor J Psychol Health 2013;18:421-443.

34. Wells A. Detached mindfulness in cognitive therapy: a metacognitive analysis and ten techniques. J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 2005;23:337-355.

35. Bowen S, Enkema MC. Relationship between dispositional mindfulness and substance use: findings from a clinical sample. Addict Behav 2014;39:532-537.

36. Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte Press; 1990.

37. Kim SJ, Jung DU, Jeon DW, Moon JJ. Effect of mindfulness-based intervention on addictive disorder. J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry 2019;23:9-16.

38. Nam S, Cho Y, Noh S. Efficacy of a mindfulness-based intervention for smartphone overuse, functional impairment, and mental health among undergraduate students at risk for smartphone addiction and the mediating role of self-regulation. Kor J Clin Psychol 2019;38:29-44.

39. Garland EL, Farb NA, Goldin P, Fredrickson BL. Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: a process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychol Inq 2015;26:293-314.

40. Yoo SK, Choi BY, Kang YS. Mediating and moderating effects of mindfulness between brooding, reflection and depression, psychological well-being. Asian J Educ 2020;21:517-545.

41. Cheng SS, Zhang CQ, Wu JQ. Mindfulness and smartphone addiction before going to sleep among college students: the mediating roles of self-control and rumination. Clocks Sleep 2020;2:354-363.

42. Liu Q, Zhou Z, Yang X, Kong F, Niu G, Fan C. Mobile phone addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: a moderated mediation model. Comput Hum Behav 2017;72:108-114.

43. Dimidjian S, Beck A, Felder JN, Boggs JM, Gallop R, Segal ZV. Webbased mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for reducing residual depressive symptoms: an open trial and quasi-experimental comparison to propensity score matched controls. Behav Res Ther 2014;63:83-89.

44. Regan T, Harris B, Van Loon M, Nanavaty N, Schueler J, Engler S, et al. Does mindfulness reduce the effects of risk factors for problematic smartphone use? Comparing frequency of use versus self-reported addiction. Addict Behav 2020;108:106435

45. Goo HK. The relationships between college studentsŌĆÖ stress, coping with stress and smart devices overdependence in the COVID-19 pandemic: the moderating effect of mindfulness. J Convergence Cult Technol 2021;7:591-597.

46. Park KY, Kim SB. The influence of middle school studentŌĆÖs test anxiety on smartphone overdependence: moderating effect of mindfulness. J Soc Sci 2020;31:265-276.

47. Carpenter JK, Conroy K, Gomez AF, Curren LC, Hofmann SG. The relationship between trait mindfulness and affective symptoms: a meta-analysis of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ). Clin Psychol Rev 2019;74:101785

48. Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 2006;13:27-45.

49. Won D, Kim KH. Validation of the Korean version of five-factor mindfulness questionnaire. Kor J Psychol Health 2006;11:871-886.

50. Lee H. The role of mindfulness in the relationship between borderline personality trait and psychological distress. Stress 2017;25:227-232.

51. Shin W, Kwon SM. The effect of dispositional mindfulness on emotional valence and arousal. Clin Psychol Kor Res Pract 2017;3:255-275.

52. H├Člzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci 2011;6:537-559.

53. Jang KH. The relationship of smart phone addiction on university students and mindfulness. Assoc East-Asia Buddhist Cult 2017;30:361-382.

54. Nam JH, Cho Y. The relationship between the job seeking stress and the internet addiction: the mediating effects of mindfulness. Korean J Mil Couns 2017;6:31-49.

55. Park JS, Chung NW. The relationship between recovering alcoholicsŌĆÖ anger and perception of emotional facial expressions: moderating effect of mindfulness. Kor J Psychol Health 2016;21:129-151.

56. Park K. The moderating effect of metacognition and mindfulness on the relation between perceived stress and depression. Kor J Psychol Health 2010;15:617-634.

57. Daubenmier J, Hayden D, Chang V, Epel E. ItŌĆÖs not what you think, itŌĆÖs how you relate to it: dispositional mindfulness moderates the relationship between psychological distress and the cortisol awakening response. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014;48:11-18.

58. Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Walsh EC, Charnigo RJ Jr, Lynam DR, Baer RA. The ŌĆ£whatŌĆØ and the ŌĆ£howŌĆØ of dispositional mindfulness: using interactions among subscales of the five-facet mindfulness questionnaire to understand its relation to substance use. Assessment 2012;19:276-286.

59. Kim WS, Jun JS. Effects of K-MBSR program on levels of mindfulness, psychological symptoms, and quality of life: the role of home practice and motive of participation. Kor J Psychol Health 2012;17:79-98.

60. Ostafin BD, Brooks JJ, Laitem M. Affective reactivity mediates an inverse relation between mindfulness and anxiety. Mindfulness 2014;5:520-528.

61. Arch JJ, Craske MG. Mechanisms of mindfulness: emotion regulation following a focused breathing induction. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:1849-1858.

62. Bae JH, Chang HK. The effect of MBSR-K program on emotional response of college students. Kor J Psychol Health 2006;11:673-688.

63. Cho S, Lee H, Oh KJ, Soto JA. Mindful attention predicts greater recovery from negative emotions, but not reduced reactivity. Cogn Emot 2017;31:1252-1259.

64. Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S, Oskamp S, editor. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park: Sage, 1988, p. 31-67.

65. Park J, Seo YS. Validation of the perceived stress scale (PSS) on samples of Korean university students. Kor J Psychol Gen 2010;29:611-629.

66. Kim BN, Lim YJ, Kwon SM. The role of decentering in the relationship between rumination and depressive symptoms. Kor J Clin Psychol 2010;29:573-596.

67. Lee JE. A comparative analysis on the ruminative thinking scales: RRS and RRQ [dissertation] Seoul, Korea University. 2016.

68. National Information Society Agency. The survey on internet overdependence 2016 [Internet]. Available at: https://www.nia.or.kr/site/nia_kor/ex/bbs/View.do?cbIdx=65914&bcIdx=18390&parentSeq=18390. Accessed May 28, 2022.

69. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications; 2017.

70. Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991.

71. Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behav Res 2007;42:185-227.

72. Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods 2002;7:422-445.

73. Muller D, Judd CM, Yzerbyt VY. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J Pers Soc Psychol 2005;89:852-863.

74. Kang GH. The effects of studentŌĆÖs stress and personal relationship on smart phone addiction. J Korea Soc Comput Inform 2015;20:147-153.

75. Kang KA, Park SH. The mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between university life stress and smartphone overuse. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc 2018;19:210-218.

76. Kim NS, Lee KE. Effects of self-control and life stress on smart phone addiction of university students. J Health Info Stat 2012;37:72-83.

77. Kang JY. The effect of stress and the way of stress coping, impulsivity of employees on smart-phone addiction [dissertation] Bucheon, Catholic University of Korea. 2012.

78. Wang JL, Wang HZ, Gaskin J, Wang LH. The role of stress and motivation in problematic smartphone use among college students. Comput Hum Behav 2015;53:181-188.

79. Ba─¤atarhan T, Siyez DM. Rumination and internet addiction among adolescents: the mediating role of depression. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 2022;39:209-218.

80. Shaw AM, Timpano KR, Tran TB, Joormann J. Correlates of Facebook usage patterns: the relationship between passive Facebook use, social anxiety symptoms, and brooding. Comput Hum Behav 2015;48:575-580.

81. Jeong GC. Relationships among mental health, internet addiction, and smartphone addiction in university students. J Korea Contents Assoc 2016;16:655-665.

82. Fuochi G, Voci A. The de-automatizing function of mindfulness facets: an empirical test. Mindfulness 2020;11:940-952.

83. Jeong JW, Lee DK, Lee SK, Cho HY, Suh JW. Mindfulness and its relationship with psychiatric symptoms, alcohol use, and personality traits in alcohol-dependent patients. J Korean Acad Addict Psychiatry 2012;16:73-78.

84. Ciesla JA, Reilly LC, Dickson KS, Emanuel AS, Updegraff JA. Dispositional mindfulness moderates the effects of stress among adolescents: rumination as a mediator. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2012;41:760-770.

85. Thompson JS, Jamal-Orozco N, Hallion LS. Dissociable associations of facets of mindfulness with worry, rumination, and transdiagnostic perseverative thought. Mindfulness 2022;13:80-91.

86. Van Dam NT, Hobkirk AL, Danoff-Burg S, Earleywine M. Mind your words: positive and negative items create method effects on the five facet mindfulness questionnaire. Assessment 2012;19:198-204.

87. Dong G, Potenza MN. A cognitive-behavioral model of internet gaming disorder: theoretical underpinnings and clinical implications. J Psychiatr Res 2014;58:7-11.

88. Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B. Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol 2006;62:373-386.

89. Choi SY. Study on validity and reliability of five facet mindfulness questionnaire (FFMQ) for measuring mindfulness meditation program before and after. J Oriental Neuropsychiatry 2015;26:181-190.

90. Kim H. The effects of mindfulness on attention regulation [dissertation] Seoul, Seoul National University. 2015.

91. Leung H, Pakpour AH, Strong C, Lin YC, Tsai MC, Griffiths MD, et al. Measurement invariance across young adults from Hong Kong and Taiwan among three internet-related addiction scales: bergen social media addiction scale (BSMAS), smartphone application-based addiction scale (SABAS), and internet gaming disorder scale-short form (IGDS-SF9) (study part A). Addict Behav 2020;101:105969