Characteristics and Effectiveness of Individual Psychotherapy for Palliative and End-of-Life Care: A Literature Review for Randomized Controlled Trials

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The introduction of psychotherapy in palliative and end-of-life care settings has become increasingly common and is effective in decreasing many psychological problems. This review reports the characteristics and effectiveness of individual psychotherapeutic interventions for patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care. In addition, the review reports the effectiveness of psychotherapies considering the expected life expectancy.

Methods

The PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library databases were searched for English-language articles published between January 2000 to May 2023.

Results

Twenty-six studies were included and classified into a total of nine types of psychotherapies, namely, dignity therapy (DT), life review therapy, narrative therapy, managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM), individual meaning-centered psychotherapy, meaning and purpose therapy, meaning-making therapy, meaning-of-life therapy, and cognitive therapy.

Conclusion

Most of the psychotherapies provided to patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care showed effectiveness in the reduction of negative emotions and positive factors related to end-of-life issues. Most studies targeted patients with advanced cancer; however, studies on DT did not limit the target group to patients with cancer. Considering the expected life expectancy, CALM was found to be suitable for patients receiving early palliative care.

INTRODUCTION

Advances in medical treatments have not only prolonged life expectancy over the past century but have also changed illness trajectories, particularly in economically developed countries. As a result of these illness trajectory changes, individuals experience physical, psychological, and spiritual difficulties ranging from days to years before death [1,2]. These difficulties have brought to the fore the need for palliative care, and a previous study showed that 38%–74% of the population needed end-of-life palliative care worldwide [3]. Among many dimensions, providing psychosocial support is a core component of palliative care [4]. Patients receiving palliative care suffer from high psychological distress, which can affect physical symptoms and poor social functioning [5]. These patients also suffer from depression, anxiety, and hopelessness, which also can negatively affect their overall quality of life [6]. However, the psychological problems among patients receiving end-of-life care can be treated by appropriate psychosocial interventions.

Since the 21 century, the introduction of psychotherapy in palliative and end-of-life care settings has become increasingly common, and its effectiveness has been confirmed. For individuals receiving palliative care, including those with advanced cancer, psychotherapy is effective in decreasing psychological symptoms and increasing existential happiness and overall quality of life [7,8].

Several review articles have focused on psychotherapy among patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care including group therapy [7-9]. Owing to tests, procedures, and treatments related to their physical diseases, patients may feel burdened, and participating in group therapy for a fixed time may be difficult. In addition, if patients are struggling to overcome their suffering, they may find it difficult to absorb the suffering of other patients in the group. Thus, patients undergoing palliative care may receive treatment in a more personal space [10]. By emphasizing the suitability of individual therapy rather than group therapy in the palliative care setting, in this review, we would like to exclude group therapy and explore the effectiveness and characteristics of individual psychotherapy more deeply. Most of the treatments were indicated for patients with advanced cancer; however, patients with other diseases receiving palliative and end-of-life care were also included. In addition, we would like to consider whether applying different psychotherapies according to the expected life expectancy of the patient group is effective. To focus on the effect of treatments on patients, articles including partners, caregivers, families, or medical staff were excluded.

METHODS

PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library were searched for studies published between January 2000 to May 2023 using the following terms in the title: “Palliative” or “End-of-life care” cross-referenced with “psychotherapy,” excluding the term “Group.” Papers published between January 2000 to May 2023 were included to determine trends in therapy over the past 20 years.

The eligibility criteria for study selection were as follows: 1) studies with randomized controlled trials (RCTs), clinical controlled trials, or waitlist controlled trials, 2) studies that investigated the effects of psychotherapy conducted in patients receiving palliative or end-of-life care, and 3) studies that were available in English.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) studies of complementary therapies including physical (yoga and physiotherapy), art, music, and aromatherapy, 2) studies including the effects of medication treatment together, 3) studies that also enrolled partners, caregivers, and family-delivered therapies, 4) group therapies, 5) review articles including meta-analysis, abstracts, posters, editorials, protocols, gray literature, conference proceedings, and studies with unavailable full texts, and 6) studies that report only qualitative results.

If a phase 3 RCT was conducted after a phase 2 RCT, the preceding study was not included in the review if the study analyzed the same outcome as the latter study. However, if the outcomes to be confirmed were different, both papers were included in the review.

RESULTS

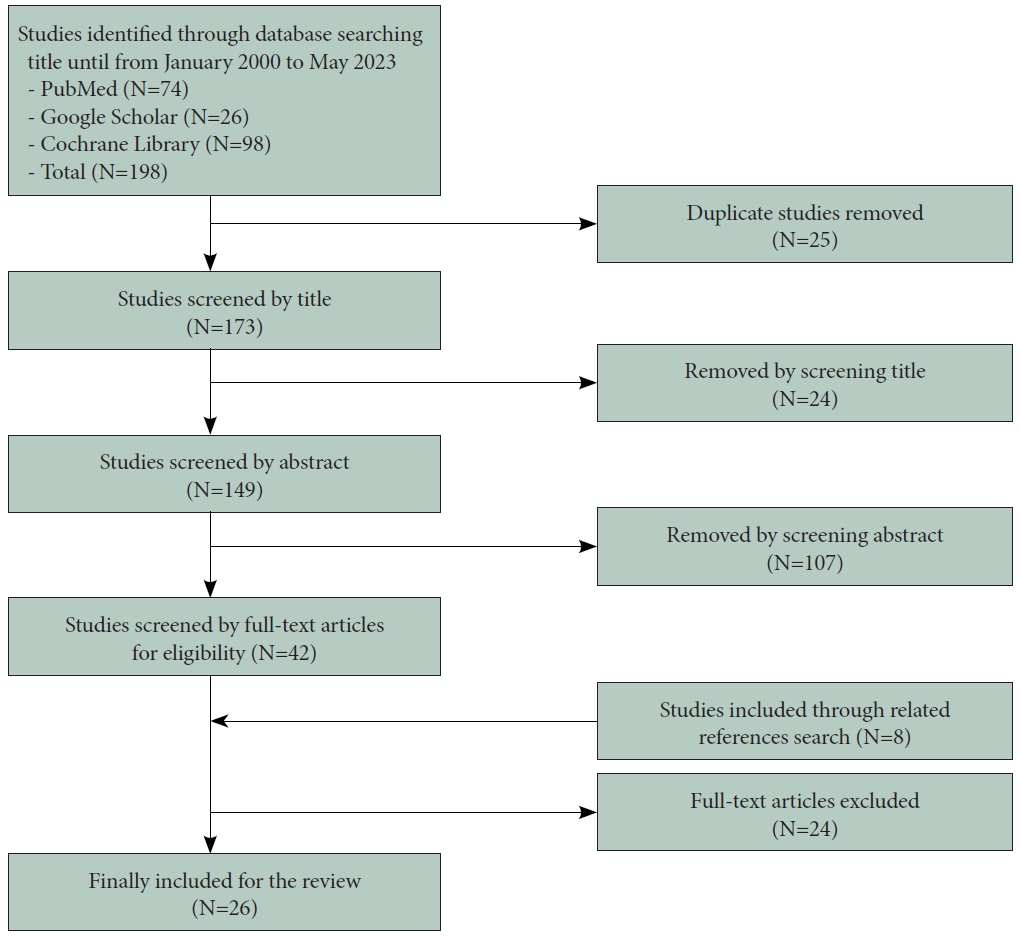

A total of 198 articles were identified through the title search. After screening of the titles and abstracts, the full texts of 42 articles were extensively reviewed by two reviewers. In addition, 8 studies were included through the related reference search by reviewers. Finally, 26 studies were included in the review. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the review process.

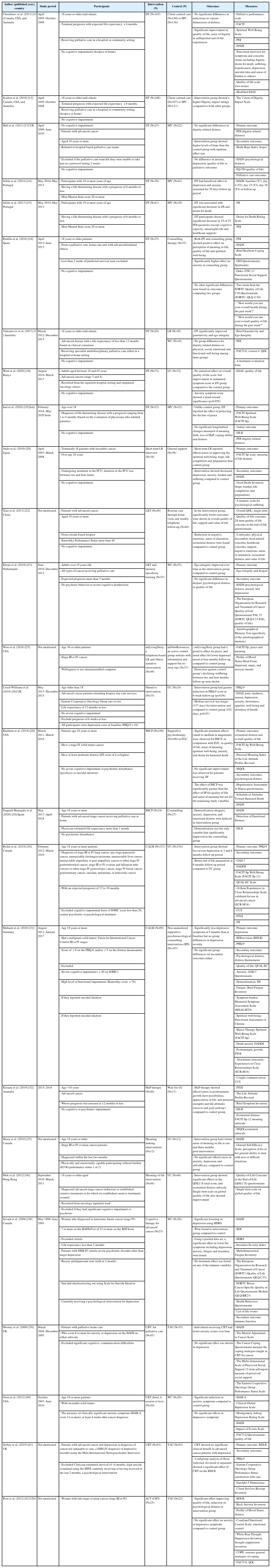

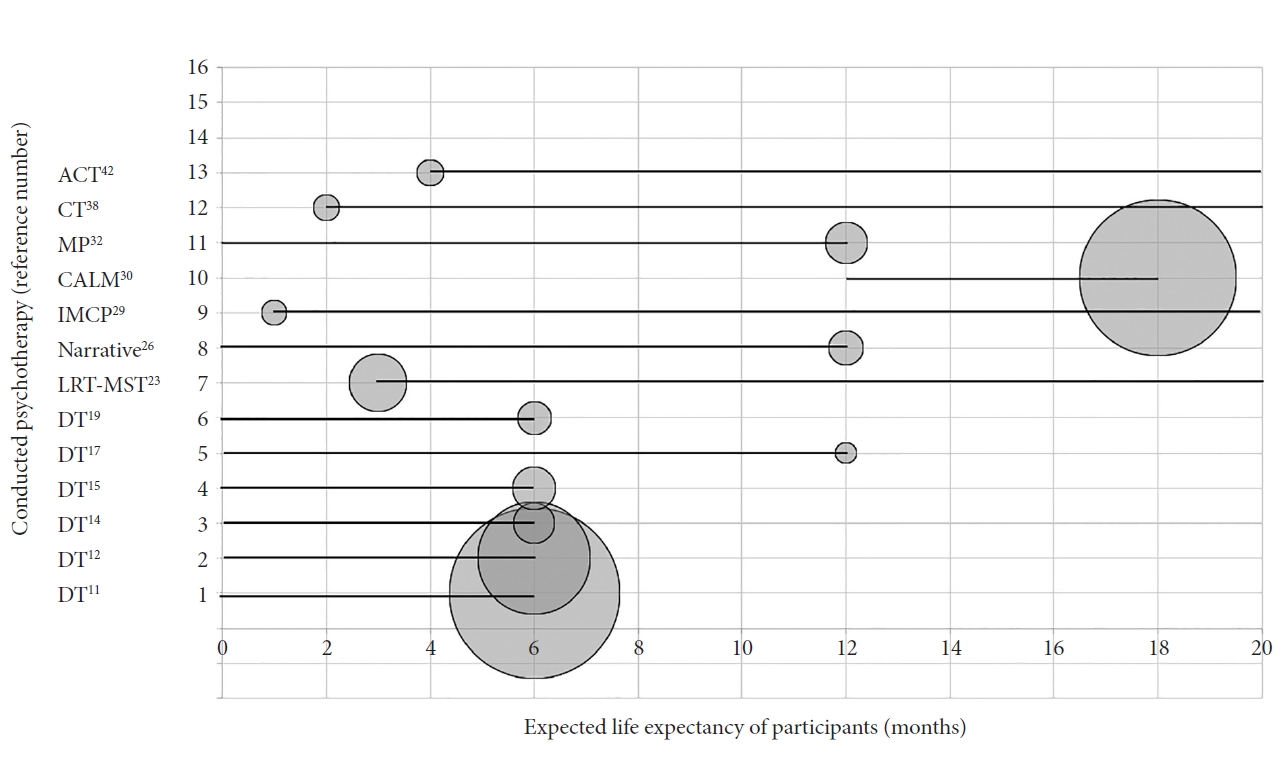

These studies were classified into a total of nine types of psychotherapies, namely, dignity therapy (DT), life review (LR) therapy, narrative therapy, managing cancer and living meaningfully (CALM), individual meaning-centered psychotherapy (IMCP), meaning and purpose (MaP) therapy, meaning-making therapy, meaning-of-life therapy, and cognitive therapy. In cognitive therapy, the treatment used in the studies was heterogeneous; however, they were classified and reviewed in the same category as cognitive or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). The overview of the reviewed studies is shown in Table 1.

Characteristics of each psychotherapy and their treatment outcomes

DT

DT is a brief, individualized psychotherapy developed to alleviate distress in patients with terminal illnesses and improve their end-of-life experiences. This treatment provides patients the opportunity to reflect on things that are important to them or other things they want to remember or convey to others. The treatment protocol shows the nine basic questions to begin this psychotherapy, reflecting the empirical model of dignity in patients.

Chochinov et al. [11] developed the DT, and their research team published their findings of the RCT study in 2011. They did not find significant differences in the distress levels estimated by standardized scales including the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy (FACIT), hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS), and modified Edmonton symptom assessment scale (ESAS) between the groups receiving DT, client-centered care, and standard palliative care. However, in the self-report of end-of-life experiences, DT was significantly more likely than other therapies to improve the quality of life and sense of dignity and help patients and families. In addition, it was better than client-centered care in improving spiritual wellbeing and standard palliative care in reducing sadness or depression.

Scarton et al. [12] conducted another RCT analysis using previous research data. Their reanalysis included 326 participants with ≤6 months of life expectancy who completed the original study [11]. This study showed a higher rating on the Dignity Impact Scale (DIS) in the DT group than in the usual care or client-centered intervention group. The DIS was used to measure the dignity effect, which can assess spiritual issues associated with the end of life.

Hall et al. [13] performed an RCT with 45 participants who received DT plus standard care or standard care alone. They showed no significant differences in dignity-related distress between the groups. However, the intervention group reported more hope than the standard care group at the 4-week follow-up.

Julião et al. [14] conducted a phase 2 RCT with 80 participants receiving end-of-life care and reported that the DT group had a beneficial effect on depression and anxiety symptoms. Another study published in 2017 by the same research team [15] measured the effect of DT on demoralization, desire for death, and sense of dignity. Results showed that all of the three domains mentioned above were associated with the therapeutic effects of DT.

Rudilla et al. [16] conducted an RCT, which enrolled 70 participants from a home care unit, who had more than 2 weeks of predicted survival. The study found that the DT or counseling group showed improvements in the perception of the meaning of life, quality of life, and spiritual well-being among the patients. However, the results for anxiety were better in the counseling group than in the DT group. This study showed that among RCTs for various conditions, DT does not show a comparative superior treatment effect to counseling.

Vuksanovic et al. [17] compared the DT group with LR therapy and waitlist control groups. DT was suggested to improve generativity and ego integrity in individuals with advanced diseases and a life expectancy of <12 months. No significant differences were found for dignity-related distress or physical, social, emotional, and functional well-being among the three study groups.

Weru et al. [18] used ESAS to measure the quality of life of 144 participants with advanced cancers. No statistically significant improvements were found in the overall quality of life of the DT group when compared with the usual care group. In the DT group, the symptom scale showed a trend toward statistical significance in anxiety.

Iani et al. [19] conducted an RCT to determine whether DT is efficacious on spiritual well-being, demoralization, and dignity-related distress. Results showed that the DT group exhibited similar levels of peace in 15–20 days of follow-up, whereas the standard palliative care group showed decreased peace during the same period. The study did not show significant differences in meaning, faith, loss of meaning, purpose, or distress among the participants.

Taken together, eight of nine studies reviewed reported that DT was more effective than usual care or other therapies, including counseling or LR. The therapeutic effects of DT have been reviewed in various aspects such as lowering depression, anxiety, demoralization, desire for death, and dignity-related distress. Moreover, enhanced sense of dignity, sense of hope and meaning of life, generativity, and ego integrity were also reported as effects of DT. Only one study did not confirm the effectiveness of DT compared with counseling [16].

LR therapy

Ando et al. [20] developed short-term LR therapy consisting of two sessions over 1 week. Before this study, the research team explored the 4-week therapy for patients with terminal cancer [21]; however, approximately 30% of the participants could not complete the study because of the rapid deterioration of their physical condition. In the first session of short-term LR, patients reviewed their lives with an interviewer to recollect and integrate their lives. In this process, the therapist records the patient’s words, draws keywords from the verbatim, and makes an album with related photos and pictures. In the second session, patients review this album with the therapist to feel the continuity of self and accept life completion. The result of the RCT of this intervention showed that the meaning-of-life subscale from FACIT-Spiritual (FACIT-Sp) scale and the hope, life completion, and preparation scores were significantly improved in the intervention group compared with those in the general support group. Moreover, depression, anxiety, burden, and suffering were alleviated to a higher degree in the intervention group than in the control group.

Xiao et al. [22] conducted a study with 80 patients receiving home-based hospice care and three sessions of LR intervention. This study suggested that the LR intervention offered improvements in psychospiritual well-being including the feeling of support, value of life, and decreased negative emotions, sense of alienation, and existential distress.

Kleijn et al. [23] showed the effectiveness of an intervention combining LR and memory specificity training in patients with cancer receiving palliative care with an expected prognosis of >3 months. This RCT suggested that the course of ego integrity improved over time in the intervention group compared with the waitlist group but had no effect on despair, psychological distress, or quality of life.

Narrative intervention

Narratives can change beliefs and motivate action and are useful for cancer communication. It can also provide opportunities to express emotions in a safe place for individuals to explore the meaning of their experience and promote coping strategies [24].

Wise et al. [25] conducted an RCT of patients with advanced cancer who received a narrative intervention, named “miLivingStory.” The three components of this intervention were storytelling, telephone interviews, and recording of the participant’s life, sharing the story on a website with support groups, and inviting guests and uploading the story in social media. Comparing the effectiveness with the control group, the intervention group showed a positive effect on peace, reduced depression in the 4-month follow-up, and protected against reduced wellbeing at the 2- and 4-month follow-ups.

Lloyd-Williams et al. [26] conducted an RCT involving patients with depression who scored ≥10 points in the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and showed that after receiving a focused narrative intervention to usual care, the score of the group with moderate-to-severe depression reduced compared with that of the usual care group. They also suggested that the group receiving this intervention appeared to have longer survival than the control group.

IMCP

Breitbart et al. [27] developed the IMCP, which was originally designed as an eight-session group-based intervention. The intervention focuses on encouraging patients with advanced cancer to share concerns related to their illness, express their emotions, and increase a sense of meaning in their lives. In their RCT for IMCP [28] compared with enhanced usual care, IMCP showed significant treatment effects on the quality of life, sense of meaning, spiritual well-being, anxiety, and desire for hastened death. In addition, compared with the supportive psychotherapy group, the IMCP intervention group showed enhanced effects on the quality of life and sense of meaning.

Fraguell-Hernando et al. [29] conducted IMCP in patients receiving home palliative care. IMCP demonstrated effectiveness in decreased levels of demoralization, depression, anxiety, and emotional distress, whereas the counseling group showed only decreased demoralization.

CALM

Rodin et al. [30] developed the brief, semi-structured psychotherapy called CALM for patients with advanced cancer to prevent depression and end-of-life distress. This therapy is compromised with 3–6 individual sessions of 45–60 min, which provide therapeutic relationship and reflective space, with attention to the four domains, namely, symptom management and communication with healthcare providers, changes in self and relations with others, spiritual well-being and sense of MaP, and mortality and future concerns. An RCT with 305 patients with advanced cancer showed that the CALM group reported less severe depression at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups and better end-of-life preparation at the 6-month follow-up than the usual care group.

Mehnert et al. [31] conducted an RCT with 206 patients with cancer to compare the effectiveness of CALM with supportive psycho-oncological counseling. The study showed that both interventions reduced depressive symptoms; however, no significant difference was found between the two groups.

MaP therapy

Kissane et al. [32] developed a therapy to enhance meaning-based coping through LR for patients with advanced cancer whose prognosis was ≤12 months and who received six manual sessions. To conduct each session, meaning-centered questions are used, which are illustrated in the MaP manual. Each session focused on cancer history and personal life, personalized therapy goals, enhancing MaP, connection with others, defining priorities with strengths and values, and consolidating the direction for the totality of life. The results of the RCT revealed that MaP therapy showed effectiveness in posttraumatic growth and positive life attitude compared with the waitlist control.

Meaning-making intervention (MMi)

MMi is a brief intervention conducted within four sessions of 30–90 min each and focuses on existential meaning. Each session is structured to deal with three tasks, namely, 1) reviewing the effect and meaning of the cancer diagnosis, 2) exploring important life events and ways of coping, related to the present cancer experience, and 3) prioritizing life and goal changes that give meaning to one’s life [33,34].

Henry et al. [35] conducted a pilot RCT with participants newly diagnosed with advanced ovarian cancer. Compared with the waitlist usual care group, the intervention group was suggested to influence the sense of meaning. The study used FACITSp-12 meaning subscale and captured the effect of MMi at 1 and 3 months post intervention. No significant effects on other measures including anxiety, depression, and self-efficacy were found following the intervention.

Meaning-of-life therapy

Mok et al. [36] developed the meaning-of-life intervention, a brief intervention to help patients receiving palliative care to reflect on their lives based on the sources of the meaning of life suggested in logotherapy. Intervention is composed of two sessions. The first session lasts for 30–60 min, which focuses on facilitating individuals about their lives with five core questions. The facilitator summarized the tape-recorded session and formulated a generalized meaning in the interview. In the second session, which continues after 2–3 days, participants verify the written summary, and this summary can be modified as needed. The results of this study revealed that the intervention demonstrated statistically significant effects on the overall quality of life score and existential distress subscale compared with the control intervention.

CBT

CBT helps individuals not only overcome fear and avoidance by being gradually exposed to situations that cause anxiety but also reconstruct irrational thoughts and beliefs that exacerbate anxiety [37]. Several research teams have developed CBT suitable for application to patients receiving palliative care and researched on its effectiveness.

Individual cognitive therapy (CT), which is composed of 8 weekly sessions and three booster sessions for women with depression and metastatic breast cancer, was conducted by Savard et al. [38] In their study, the intervention group showed significantly fewer symptoms including depression using the Hamilton depression rating scale measures than the control group. Moreover, they found that by using a pooled dataset, the effects were observed as a reduction in symptoms including depression, anxiety, fatigue, and insomnia and were sustained well at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups.

Moorey et al. [39] conducted an RCT involving patients receiving palliative home care. Home care nurses received training in CBT or continued the usual care. The trial enrolled patients who had anxiety and depression symptoms based on HADS and showed that the CBT group had significantly decreased anxiety levels but not depression.

Greer et al. [40] developed a brief CBT for patients with terminal cancer who had anxiety scores of ≥14 based on the Hamilton anxiety rating scale. After six CBT sessions, the anxiety level of the intervention group reduced compared with that of the waitlist control group. Similar to the results of Moorey et al. [39], this study showed that CBT had no significant effect on depressive symptoms.

In the study of 12 sessions of manualized CBT for patients with advanced cancer who have depression and estimated survival of >4 months, Serfaty et al. [41] tried to find the therapeutic effects on mood symptoms. However, the intervention group did not show any clinical benefit with depression compared with the treatment-as-usual (TAU) group. Subgroup analysis including widowed, divorced, or separated participants showed that CBT exerted a significant effect on depressive symptoms.

In the study of patients with late-stage ovarian cancer, Rost et al. [42] used acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for the intervention group. ACT is a recent variant of CBTs, which explicitly targets avoidance by enhancing experiential acceptance [43]. After 12 face-to-face meetings and interventions following the ACT or TAU, the ACT group showed much more improvement in the quality of life and reduction in psychological distress than the TAU group. It had no significant direct effects on anxiety or depressive symptoms.

Although evaluating and synthesizing the effectiveness of CBT using different protocols, most studies have confirmed that CBT is effective in reducing anxiety among patients receiving end-of-life care. However, no results were consistent on whether depressive symptoms were reduced.

Application of psychotherapy by life expectancy

In 13 of the 26 studies, the life expectancy of the participants was considered in the inclusion or exclusion criteria when recruiting participants. These studies are presented in Figure 2, along with the number of participants receiving psychotherapy. Studies dealing with the therapeutic effect of DT limit the expected life expectancy of the participants to <6 months or <12 months [11,12,14,15,17,19]. Among studies dealing with other psychotherapies, studies specifying the expected life expectancy of the participants target patients with a life expectancy of <6 months for narrative intervention [26] and <12 months for MaP therapy [32]. Moreover, certain studies have specified the minimum life expectancy instead of the maximum life expectancy. Among the reviewed studies, only patients with a life expectancy of >1 month in the IMCP study [29], >2 months in the CT study [38], >3 months in the LRT-MST study [23], and >4 months in the ACT study were recruited [41]. In the CALM study, both minimum and maximum life expectancies were specified, and patients with a life expectancy of 12–18 months were included [30].

Life expectancy and conducted psychotherapy. Circle diameter: number of participants with intervention.

In Figure 2, for each study, the diameter of the circle corresponds to the number of participants who received each psychotherapy. If the sample size is too small, obtaining adequate results can be difficult even in strictly executed studies [44]. The studies reviewed have produced specific results; however, some are preliminary studies considering the number of participants [45]. Therefore, we tried to compare the sample size of the study according to each psychotherapeutic method by indicating the number of participants. In this figure, the number of participants was compared only for studies with a specified expected survival period, and the number of participants for all studies can be confirmed in Table 1.

The remaining 13 studies did not mention the patient’s life expectancy, and classifying participants according to life expectancy was difficult because of the mixed use of terms such as “terminal diseases,” “terminal cancer,” or “advanced cancer.”

DISCUSSION

Most of the reviewed studies have targeted the reduction of negative emotions as outcomes of treatment including depression, anxiety, emotional distress, burden and suffering, desire for death, and demoralization. DT [11,14-16,18,19], LRT [20,22], narrative intervention [25,26], IMCP [28,29], CALM [30,31], meaning-of-life therapy [36], and most of the CBT [38-40,42] were found to reduce negative emotions among patients receiving palliative care. Studies have also noted that psychotherapies not only reduced negative emotional factors but also increased positive factors. These include the sense of dignity, sense of hope and peace, meaning and value of life, ego integrity, generativity, psychological or spiritual wellbeing, posttraumatic growth, positive life attitude, and life completion and preparation. Psychotherapies that enhance positive life factors include DT [11-13,15-19], LRT [20,22,23], narrative intervention [25], IMCP [28], CALM [30], MaP therapy [32], MMi [35], meaning-of-life therapy [36], and ACT in CBT, which improved the quality of life [42]. In other words, the results show an increase in positive factors for life in all types of psychotherapies reviewed but not in most of the CBT. In this review, treatments addressed other than CBT, commonly emphasize the meaning of life that individuals can feel at the end of their lives and focus on dealing with this meaning in a comfortable environment. The effect of these therapies can also be linked to finding the meaning of life, promoting positive views on life.

As for the participant group, most studies have targeted patients with metastatic or advanced cancer. However, in the case of DT, more than half of the reviewed studies did not limit the target group to patients with cancer [11,12,14-17,19]. The fact that DT does not limit the target group to these patients compared with other psychotherapies may mean that this treatment can be comprehensively applied regardless of the characteristic disease progression of patients with cancer. According to Chochinov et al. [11], the developer of this treatment method, DT targets patients who reach the end of their lives with an expected life expectancy of <6 months. The nine questions given during the psychotherapeutic process take the form of a will that they want to remember personally or to be remembered by their loved ones. This helps all patients who face imminent death regardless of the disease course to face death with dignity.

When psychotherapy was classified according to the expected life expectancy, psychotherapy was conducted on patients with a life expectancy of ≤6 months or ≤12 months in narrative intervention [26], MaP [32], and DT [11,12,14,15,17,19]. In studies that mentioned the minimum life expectancy of patients, the minimum life expectancy was at least 1–4 months for other psytchotherapies [23,29,38,41]. This shows that most therapies simply target patients who are about to die. However, CALM therapy targets patients with advanced cancer who cannot be treated but have an expected prognosis of at least 1 year [30]. In other words, it targets patients who are expected to die from diseases, but death is not imminent. Early palliative care performs well in many ways [46,47]; however, early palliative care for psychological problems has not been well-organized. CALM therapy aims to provide early psychological palliative care to patients who expect death but have to live with the disease; it is different from other psychotherapies dealing with impending death.

The studies reviewed included various sample sizes of patients who participated in the psychotherapeutic intervention of the control group; however, in most cases, recruiting more than 100 participants in each arm was challenging. There can be two main reasons for this difficulty in participant recruitment. First, patients may not be the priority participants of psychotherapy or associated research if they are in a confusing situation. Patients must adapt to complex medical systems and make important treatment decisions while enduring their pain in situations such as cancer progression, exacerbation, and recurrence. Owing to the unique characteristics of these patients, study participation may not be a priority for most patients [10]. Second, even if they agreed to participate in the study, there may be many situations in which continued participation in psychotherapy and related research is difficult because of their physical condition, and deaths before completing the study protocol may also be frequent. Thus, compared with other studies that have investigated treatment outcomes, patient enrollment was difficult. Despite these implications, a total of five studies that have reviewed therapies such as DT [11,12], IMCP [28], and CALM [30,31] were completed with more than 100 participants per arm, which can be seen as fairly large-scale studies. Considering the characteristics of these patient groups, research must be conducted with large patient groups, and appropriate training of therapists to perform psychotherapy is also essential.

CONCLUSION

Most psychotherapies provided to patients receiving palliative and end-of-life care showed effectiveness in reducing negative emotions including depression, anxiety, emotional distress, burden and suffering, desire for death, and demoralization. Moreover, psychotherapies improve positive factors at the end of life including dignity, sense of hope and peace, meaning and value of life, ego integrity, generativity, psychological or spiritual wellbeing, posttraumatic growth, positive life attitude, and life completion and preparation, although the effects on each variable varied or absent depending on the study. Most studies have targeted patients with advanced cancer. However, studies on DT did not limit the target group to patients with cancer. Considering the expected life expectancy, CALM was found to be suitable for patients receiving early palliative care compared with other psychotherapies.

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Kyungmin Kim, Jungmin Woo. Data curation: Kyungmin Kim. Methodology: Kyungmin Kim, Jungmin Woo. Formal analysis: Kyungmin Kim, Jungmin Woo. Investigation: Kyungmin Kim, Jungmin Woo. Writing—original draft: Kyungmin Kim. Writing—review & editing: Kyungmin Kim, Jungmin Woo.

Funding Statement

None

Acknowledgements

None