|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 21(5); 2024 > Article |

|

Abstract

Objective

Methods

Results

Notes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Seockhoon Chung, a contributing editor of the Psychiatry Investigation, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or decision to publish this article. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Asma In├©s Sana Jrad, Youngseok Yi, Seockhoon Chung, Jeong Hye Kim. Data curation: Youngseok Yi, Eulah Cho, Inn-Kyu Cho, Dongin Lee, Jiyoung Kim. Formal analysis: Asma In├©s Sana Jrad, Byeongha Yoon, Seockhoon Chung. Methodology: Asma In├©s Sana Jrad, Seockhoon Chung, Jeong Hye Kim. WritingŌĆöoriginal draft: all authors. WritingŌĆöreview & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

None

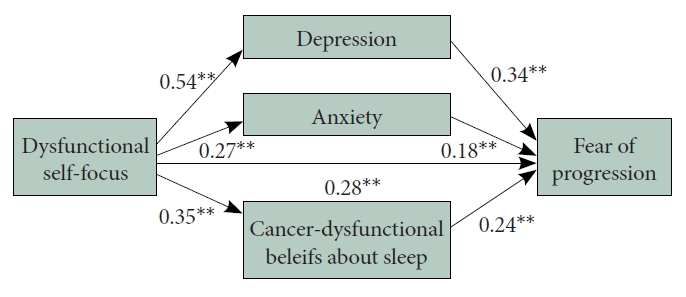

Figure┬Ā1.

Table┬Ā1.

Values are presented as number (%) or mean┬▒standard deviation.

FoP-Q-SF, Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Items; STAI-S, State subcategory of the State and Trait of Anxiety Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index, C-DBS, Cancer-related Dysfunctional Beliefs about Sleep scale; NRS, numeric rating scale; DSAS, Dysfunctional Self-focus Attribution Scale

Table┬Ā2.

| Variables | Age | FoP-Q-SF | PHQ-9 | STAI-S | ISI | C-DBS | Pain-NRS | Fatigue-NRS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoP-Q-SF | -0.17* | |||||||

| PHQ-9 | 0.07 | 0.60** | ||||||

| STAI-S | -0.03 | 0.38** | 0.24** | |||||

| ISI | 0.10 | 0.34** | 0.49** | 0.14* | ||||

| C-DBS | -0.13 | 0.47** | 0.30** | 0.19* | 0.40** | |||

| Pain-NRS | 0.04 | 0.24** | 0.36** | 0.05 | 0.26** | 0.24** | ||

| Fatigue-NRS | -0.02 | 0.37** | 0.48** | 0.11 | 0.43** | 0.33** | 0.39** | |

| DSAS | -0.12 | 0.58** | 0.54** | 0.27** | 0.31** | 0.35** | 0.11 | 0.29** |

FoP-Q-SF, Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items; STAI-S, State subcategory of the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; C-DBS, Cancer-related Dysfunctional Beliefs about Sleep scale; NRS, numeric rating scale; DSAS, Dysfunctional Self-focus Attribution Scale

Table┬Ā3.

FoP-Q-SF, Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items; STAI-S, State subcategory of the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory; ISI, Insomnia Severity Index; C-DBS, Cancer-related Dysfunctional Beliefs about Sleep scale; NRS, numeric rating scale; DSAS, Dysfunctional Self-focus Attribution Scale

Table┬Ā4.

SE, standard error; CI, confidence interval; DSAS, Dysfunctional Self-focus Attribution Scale; FoP-Q-SF, Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items; STAI-S, State subcategory of the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory; C-DBS, Cancer-related Dysfunctional Beliefs about Sleep scale

REFERENCES