|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 12(3); 2015 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

Patients visiting the emergency department (ED) after a suicide attempt are generally assessed for suicide risk by psychiatric residents. Psychiatric residents' competence in evaluating the risk posed by the patients who attempted suicide is critical to preventing suicide.

Methods

We investigated factors considered important by psychiatric residents when evaluating suicide risk. This study included 140 patients admitted to the ED after attempting suicide. Psychiatric residents rated patients' severity of current and future suicide risk as low/moderate/high using the Brief Emergency Room Suicide Risk Assessment (BESRA). The association between each BESRA variable and level of suicide risk was analyzed.

Results

Many factors were commonly considered important in evaluating the severity of current and future suicide risk. However, the following factors were only associated with future suicide risk: female gender, having no religion, family psychiatric history, history of axis I disorders, having a will, harboring no regrets, and social isolation.

South Korea, with 31.7 persons committing suicide per 100,000 people each year, has the highest suicide rate among the members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).1 The Korean government initiated its second national suicide prevention 5-year plan in 2009 to address the problem. The Korean National Emergency Department Information System has estimated that more than 40,000 patients are admitted to the emergency department (ED) due to suicide attempts.2 Therefore, the ED is an important site for the prevention of further suicide attempts.

Patients admitted to the ED after a suicide attempt are generally assessed for suicide risk by psychiatric residents. The practice guidelines of the American Psychiatry Association recommends evaluating various domains such as current presentation of suicide, history of psychiatric illness, psychosocial situation, and individual strengths and vulnerabilities when assessing these patients who have attempted suicide.3 Accordingly, psychiatric residents not only evaluate the severity of the current suicide attempt but also assess the risk of future reattempts by considering various factors. Psychiatric residents also evaluate patients referred from primary physicians or physicians of other departments. Therefore, these residents are expected to evaluate patients in greater detail and to assess suicide risk more comprehensively. Moreover, the ability of psychiatric residents to evaluate the risk posed by suicidal patients is critical for suicide prevention because their decisions affect the patients' immediate safety and plans for future treatment. Consequently, all psychiatrists are expected to acquire suicide risk assessment skills as a core competency during their residency training.4

Competence in this domain is developed and enhanced through appropriate training; appropriate training should rest on an understanding of the process by which psychiatric residents evaluate and make decisions about patients' suicide risk. Several studies have investigated knowledge about how primary physicians and non-psychiatric residents evaluate suicide risk and provide treatment for the patients who have attempted suicide. A previous study reported that residents in emergency medicine do not consider a history of suicide attempts to be a critical factor in deciding whether or not to refer patients to the psychiatric department.5 Other studies have suggested that primary physicians and non-psychiatric residents consider patients' depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation, and history of suicidal behavior as important risk factors predicting future reattempts.67 However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined the process by which psychiatric residents evaluate the suicide risk of patients who have attempted suicide.

The present study investigated which of the currently recognized suicide risk factors are considered to be important by psychiatric residents when they evaluate the severity of the current suicide attempt and the risk of future attempts in patients admitted to the ED.

This study included a total of 140 patients who attempted suicide and were admitted to the ED of Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital between December 2009 and March 2011. Each patient was interviewed and assessed by 1 of 16 psychiatric residents who participated in the assessment process. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital, College of Medicine at The Catholic University of Korea.

All patients admitted to the ED after attempting suicide were referred to psychiatric residents and a comprehensive interview was conducted in the ED. During the interview, a complete mental examination was performed. Information about demographic and clinical characteristics, the presenting suicidal behavior, and the patients' resources were also collected using the Brief Emergency Room Suicide Risk Assessment (BESRA). The BESRA is an instrument developed by our research team to help clinicians make rapid and accurate decisions in the ED when assessing patients who have attempted suicide (Supplementary Figure 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). The suicide risk factors and criteria in the BESRA were chosen based on guidelines presented in a widely used psychiatric textbook.8

The BESRA also solicits detailed information about the presenting suicide attempt in terms of established risk factors and reliable and valid risk/rescue-rating scales.9 A higher risk-rating score indicates that the patient's suicide attempt was more life threatening, whereas a higher rescue-rating score suggests that the attempt was less serious and the patient had a higher chance of being rescued.

The medical lethality of the presenting suicide attempt was also assessed using the item addressing "method and lethality of method" from the Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII) developed by Linehan.10 The lethality scores ranged from 1 to 6 (1=very low, 2=low, 3=moderate, 4=high, 5=very high, 6=severe). The psychiatric residents were instructed to evaluate the likelihood of the presenting suicide attempt to be fatal (severity of current suicide) and the risk for future reattempts (future suicide risk) as mild, moderate, or high based on these comprehensive psychiatric assessment factors.

To ensure that all psychiatric residents understood the BESRA, they received regular instruction from the two psychiatry specialists (a professor and a clinical instructor of psychiatry). The two psychiatry specialists conceived the BESRA themselves, so they were completely familiar with the evaluation tool. Moreover, consensus meetings between the two psychiatry specialists and all the residents were held biweekly to verify or correct dubious criteria (i.e., social economic status, level of achievement, and others).

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis System software package (Version 9.2) (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The authors examined associations between independent (each BESRA variable) and dependent (level of suicide risk: low/moderate/high) variables. Analyses were performed for both the severity of the current suicide attempt and the risk of a future suicide. Data on categorical variables were analyzed using a chi-square test. Continuous variables were analyzed with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a post hoc test.

Of the 140 participants, 54 (38.6%) were males and 86 (61.4%) were females. The mean age of the males was 48.1± 18.9 and that of the females was 40.0±17.3 (p<0.05). In terms of the severity of the current suicide attempt, the psychiatric residents assessed 24 patients (17.1%) as low risk, 75 (53.6%) as moderate risk, and 41 (29.3%) as high risk. Regarding the future suicide risk of the same patients, 22 (15.7%), 73 (52.1%), and 45 (32.1%) were assessed as low, moderate, and high risk, respectively.

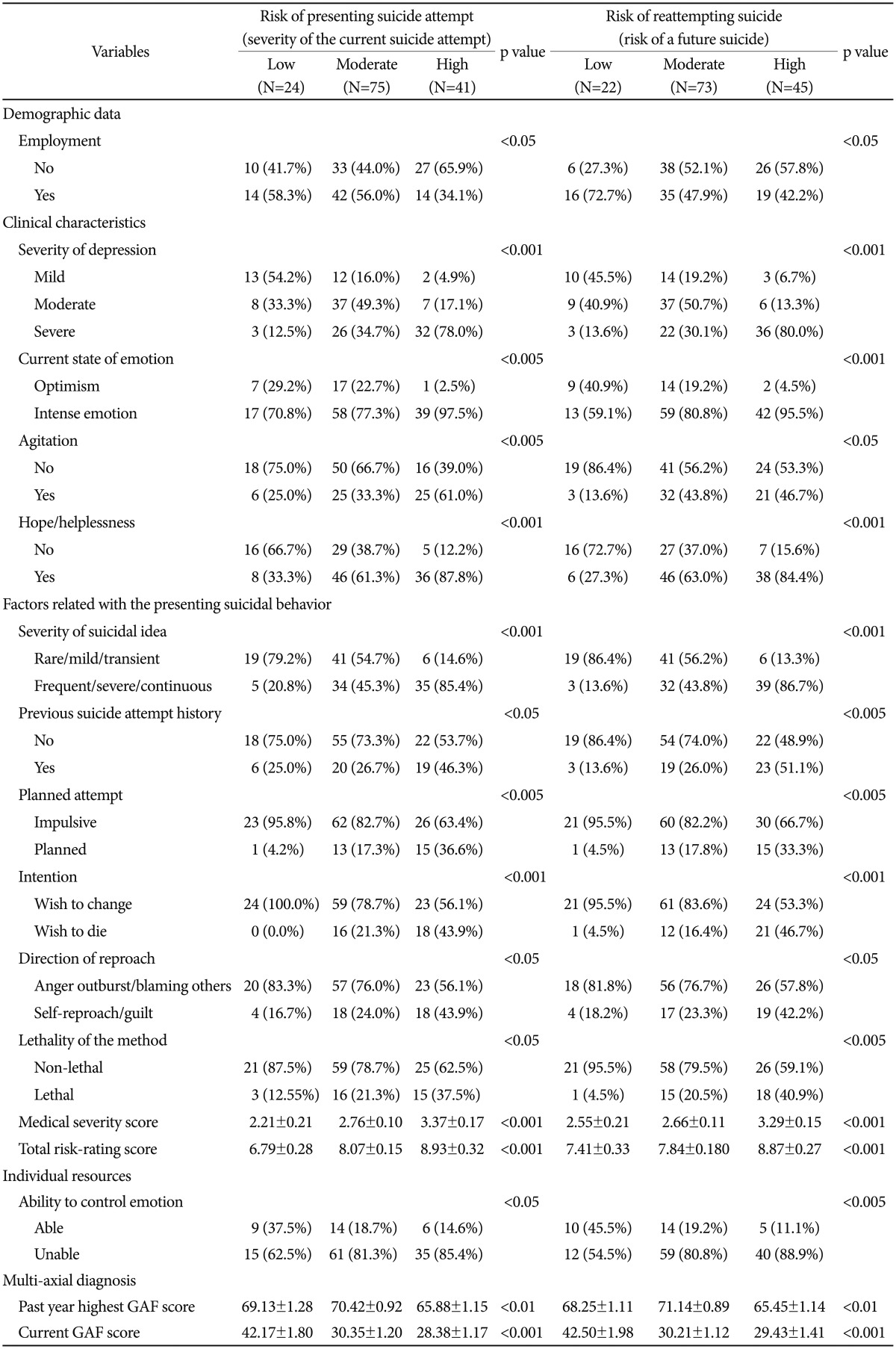

Psychiatric residents considered the following factors as commonly important for the severity of the current suicide attempt and the risk of a future suicide attempt. Among demographic characteristics, they considered employment status to be highly important. Among clinical characteristics, they regarded severity of depression, current emotional state, degree of agitation, and level of hopelessness/helplessness to be significant. In terms of presenting suicidal behavior, severity of suicidal ideation, history of previous suicide attempts, whether the attempt was planned, intentions related to the attempt, direction of any feeling of reproach, lethality of the method, the medical severity score, and the total risk-rating score were significant. Of individual's psychiatric resources, the ability to control emotion, the highest global assessment of functioning (GAF) score over the past year, and the current GAF score were important (Table 1).

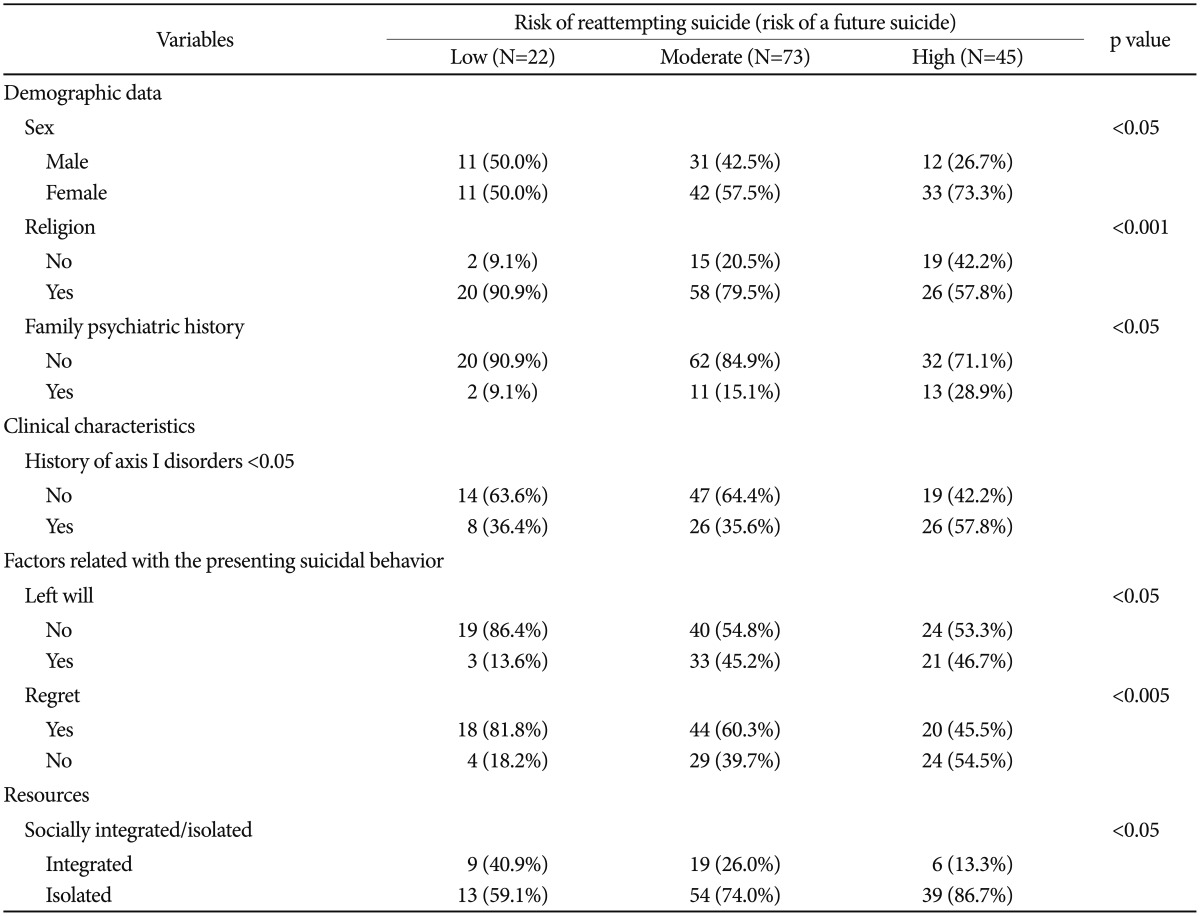

Sex, religion, family psychiatric history, history of axis I disorders, existence of a will, having regrets, and social isolation were important only for future suicide risk (Table 2). Patients' age, marital or socioeconomic status, medical illness, personality disorder, psychotic state, and precipitating events were not statistically related to either the severity of the current suicide attempt or to the risk of future suicide.

This study investigated the factors considered important by psychiatric residents when assessing the severity of the current suicide attempt and the risk of a future suicide in patients presenting to the ED for a suicide attempt. In accordance with previous studies, numerous recognized suicide risk factors were identified as commonly important for the severity of the current suicide attempt and the risk of a future suicide.1112 Evaluations of future suicide risk included several additional factors: female sex, having no religion, family psychiatric history, history of axis I disorders, the existence of a will, having no regrets, and social isolation.

It is generally known that acute suicide risk factors are usually treatable or modifiable.13 Our results, in close agreement with previous studies, showed that demographic and clinical characteristics commonly considered important in evaluating the severity of the current suicide attempt and the risk of a future suicide attempt were all modifiable factors (i.e., demographic data: employment status; clinical characteristics: severity of depression, current emotional state, agitation, hope/helplessness). In contrast, with the exception of religious status, demographic and clinical characteristics perceived to be important only for the risk of a future suicide attempt were all non-modifiable factors (i.e., demographic data: sex and family psychiatric history; clinical characteristics: history of axis I disorders). The psychiatric residents also considered tangible evidence showing the patient's determination to commit suicide, including leaving a will or not regretting their suicidal behavior, as important indicators of the risk for future suicide attempts. Additionally, social isolation was the only significant factor within the social support category in assessing suicide risk and this factor was significant only for the risk of a future suicide attempt. Consistent with our results, previous studies have indicated that a lack of a social network and social isolation are important predictors of suicide reattempts.1415 Evidently, social isolation renders rescue after a suicide attempt less likely. Accordingly, psychiatric residents may have emphasized social isolation when they assessed the risk of future suicide attempts.

Patients' age, marital or socioeconomic status, medical illness, personality disorder, psychotic state, and precipitating events were not important factors related to either the severity of the current suicide attempt or the risk of future suicide attempts, but these factors are generally acknowledged as important in the assessment of suicide risk.31415 The reason is unclear, but a small sample size or the psychiatric residents' greater emphasis on other factors could have been the cause. Given that these factors are generally considered important, further training may be required for residents to ensure that they are not overlooked in the future.

This study has several limitations. First, we did not include patients who attempted suicide but were not able to participate in the psychiatric interview due to a serious medical condition resulting from the attempt. This exclusion of patients with a higher suicide risk may have caused a selection bias, especially in evaluations of the severity of the current suicide attempt. Second, all psychiatric residents who participated in this study were working at the same institution. The particular training at our institution may have influenced the assessment process, limiting the generalization of our results to other institutions. The small number (n=16) of psychiatric residents who participated in our study is also a limitation. Finally, the study also reminds us of the limitation in rating static risk factors when assessing suicide risk. Studies have emphasized such limitations in the simple categorization of risk factors and have highlighted the importance of comprehensive evaluations of patients' mental health when practicing suicide risk evaluations.161718 Similarly, individuals with multiple high-risk factors were not always regarded as having a high suicide risk, whereas only one or two risk factors led psychiatric residents to rate certain patients as having a high suicide risk.

Despite these limitations, our study has several important implications. To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the process by which psychiatric residents evaluate the suicide risk of patients who have presented to the ED after a suicide attempt. The study also addressed the importance of analyzing and understanding the process by which psychiatric residents evaluate individuals who have attempted suicide. Additionally, our results may provide a guide for future studies examining similar relevant issues.

In conclusion, psychiatric residents' ability to correctly evaluate suicide risk is critical for preventing patients who have already attempted suicide from reattempting. Thus, it is of utmost importance to appropriately train psychiatric residents regarding suicide risk assessment. Gaining insight into the process by which psychiatric residents assess patients' suicide risk can lay the cornerstone for proper training. This study suggests that psychiatric residents use diverse factors when assessing suicide risk. It also shows that psychiatric residents might put additional emphasis on non-modifiable demographic and clinical factors, concrete evidence showing suicide determination, and social isolation to assess the risk for a future suicide attempt. Additional studies with a greater number of psychiatric residents from diverse institutions and countries are needed to further shed light on this issue.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://dx.doi.org/10.4306/pi.2015.12.3.324.

Supplementary Figure 1

Brief Emergency Room Suicide Risk Assessment (BESRA). SES: social economic status, MI: myocardial Infarction, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CKD: chronic kidney disease, CVA: cerebrovascular accident.

References

1. Statistics Korea. 2011 Cause of death. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2011.

2. Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In-Depth Analysis of 2005 Hospital Discharge Injury Surveillance Data and Feasibility for Coordinated Injury Data System. Seoul: Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention; 2007.

3. Practice guideline for the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors. Am J Psychiatr 2003;160(11 Suppl):1-60.

4. Scheiber SC, Kramer TSM, Adamowski SE. Core Competence for Psychiatric Practice: What Clinicians Need to Know. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2003.

5. Jo SJ, Lee MS, Yim HW, Kim HJ, Lee K, Chung HS, et al. Factors associated with referral to mental health services among suicide attempters visiting emergency centers of general hospitals in Korea: does history of suicide attempts predict referral? Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2011;33:294-299. PMID: 21601727.

6. Schulberg HC, Bruce ML, Lee PW, Williams JW Jr, Dietrich AJ. Preventing suicide in primary care patients: the primary care physician's role. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:337-345. PMID: 15474633.

7. Vannoy SD, Fancher T, Meltvedt C, Unutzer J, Duberstein P, Kravitz RL. Suicide inquiry in primary care: creating context, inquiring, and following up. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:33-39. PMID: 20065276.

8. Misson H, Mathieu F, Jollant F, Yon L, Guillaume S, Parmentier C, et al. Factor analyses of the Suicidal Intent Scale (SIS) and the Risk-Rescue Rating Scale (RRRS): toward the identification of homogeneous subgroups of suicidal behaviors. J Affect Disord 2010;121:80-87. PMID: 19524302.

9. Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Brown MZ, Heard HL, Wagner A. Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII): development, reliability, and validity of a scale to assess suicide attempts and intentional self-injury. Psychol Assess 2006;18:303-312. PMID: 16953733.

10. Hawton K, Casañas I, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2013;147:17-28. PMID: 23411024.

11. Haw C, Hawton K, Niedzwiedz C, Platt S. Suicide clusters: a review of risk factors and mechanisms. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2013;43:97-108. PMID: 23356785.

12. Fawcett J. Treating impulsivity and anxiety in the suicidal patient. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001;932:94-102. discussion 102-105PMID: 11411193.

13. Johnsson Fridell E, Ojehagen A, Träskman-Bendz L. A 5-year follow-up study of suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:151-157. PMID: 8739657.

14. May AM, Klonsky ED, Klein DN. Predicting future suicide attempts among depressed suicide ideators: a 10-year longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46:946-952. PMID: 22575331.

15. Petrie K, Chamberlain K, Clarke D. Psychological predictors of future suicidal behaviour in hospitalized suicide attempters. Br J Clin Psychol 1988;27(Pt 3):247-257. PMID: 3191304.

16. McPherson A. An overview of the assessment tools available to mental health professionals to help determine patients at risk of suicide. Int J Psychiatr Nurs Res 2005;10:1129-1142. PMID: 15715322.

17. Large M, Ryan C Nielssen O. The validity and utility of risk assessment for inpatient suicide. Australas Psychiatry 2011;19:507-512. PMID: 22077302.

18. Large M, Smith G, Sharma S, Nielssen O, Singh SP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical factors associated with the suicide of psychiatric in-patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;124:18-29. PMID: 21261599.