|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 13(1); 2016 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

A community survey was performed to investigate the factors and perspectives associated with happiness among the elderly in Korea (≥60 years).

Methods

Eight hundred volunteers selected from participants in the Ansan Geriatric study (AGE study) were enrolled, and 706 completed the survey. The Happiness Questionnaire (HQ), which asks four questions about happiness, was administered. To explore the relationship between happiness and depression, the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) also were administered.

Results

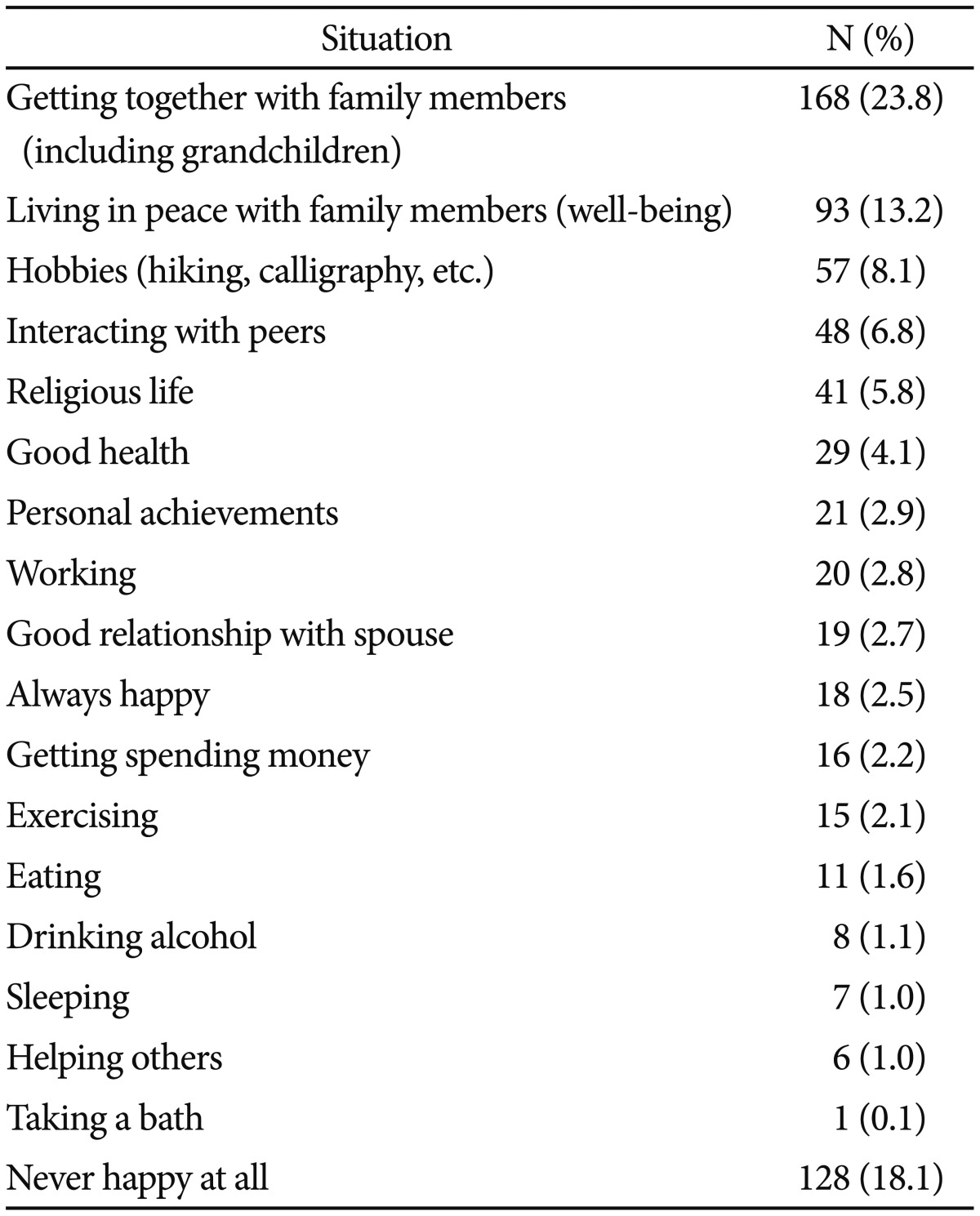

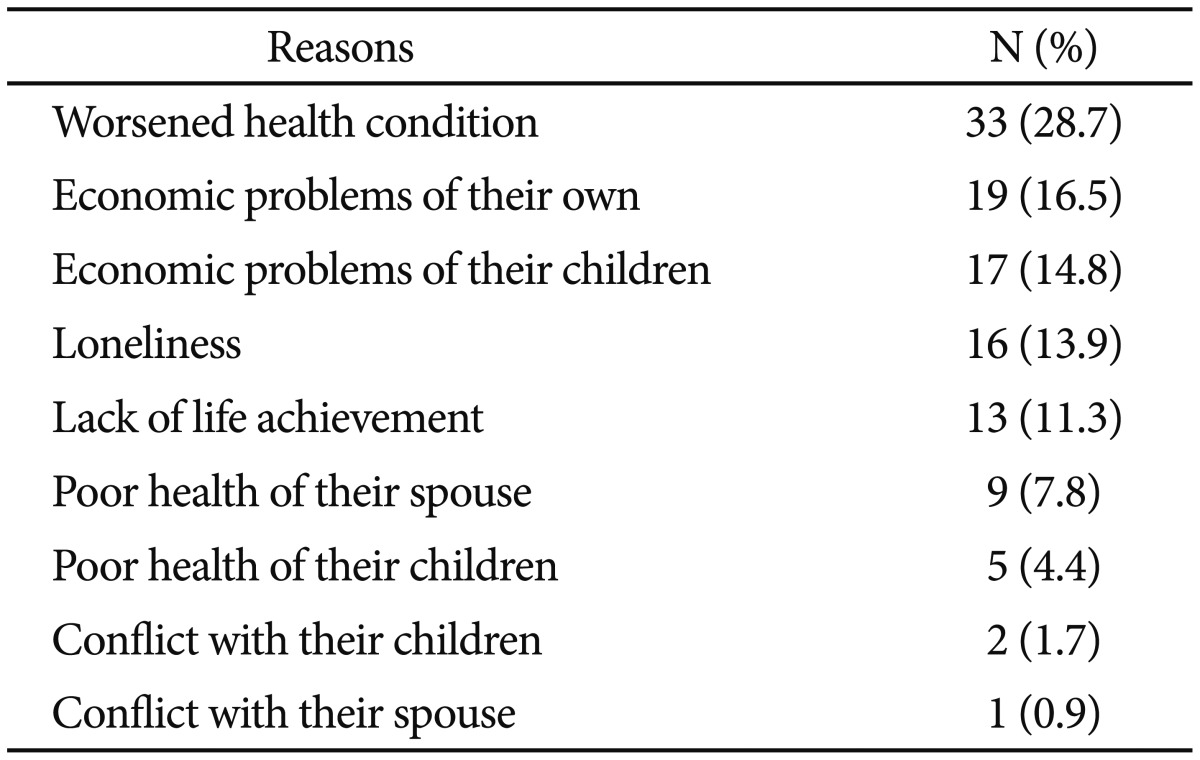

The participants' average level of happiness, determined using a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) of the HQ, was 64.7±26.0. The happiest situations for most people were "getting together with family" (23.8%) and "living in peace with family members (well-being)" (13.2%). Frequent reasons for not being happy were "worsened health condition" (28.7% of the not-happy group), "economic problems of their own" (16.5%), and "economic problems of their children" (14.8%). The participants' choices regarding the essential conditions for happiness were "good health" (65.3%) and "being with family" (20.5%). The BDI and GDS scores were negatively related to the happiness score. A preliminary scale [Happy (Haeng-Bok, 幸福) aging scale] based on the HQ for measuring the happiness level of the Korean elderly was suggested for follow-up studies.

Conclusion

The most important factors determining the happiness of the community-dwelling elderly in Korea were good family relationships, economic stability, and good health. A higher depression score negatively impacted happiness among Korean elders. Further studies on the factors in their happiness are required.

The aging of society is a global trend. South Korea is no exception: 11.4% of its population was elderly in 2011, but this figure is anticipated to approximately double to 24.3% by 2030.1 An aging society is accompanied by increased social and economic burdens. For example, the cost to support the elderly was 15.0% of Korea's Gross Domestic Product in 2010, meaning that every 6.6 economically active people (aged 15-64 years) maintained one elderly person, and it is predicted that every two working people will support each elderly person in 2040 if low birth rates in Korea continue. Due to the extension of life spans, geriatric diseases have become more prevalent than before, and these further contribute to the increasing social burden related to aging. In Korea, medical expenses from national health insurance for patients over 64 years of age in 2009 accounted for 30.5% of total medical costs.

Recently, as the elderly population has grown rapidly and their social costs have increased, the lives of elderly people have come to receive more attention than before. In particular, the health problems of old age have become important public issues.234 However, current public health policies for the elderly have been focused on physical disorders such as hypertension, cerebrovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus. In addition to the fact that mental health has not been given enough public attention, current mental health services and research merely focus on mental diseases and their associated morbidity. Many aspects of the lives of the elderly deserve attention. There have been few previous studies on the happiness of elderly people, and we aimed to investigate the factors and perspectives associated with happiness among the community-dwelling elderly in Korea.

This research contributes to the literature in several ways. First, we provide an analysis of the determinants of happiness in the Korean elderly, particularly in relation to depression. Second, we provide insights for policy makers and professionals to improve their perception and understanding of the lives of the Korean elderly. Third, our results could be used as information for creating programs to promote and provide suitable services to enhance the happiness of the elderly.

Eight hundred volunteers were recruited from among participants of the Ansan Geriatric study (AGE study). The AGE study, which started in May 2002 and is still in progress, has investigated depression, cognitive decline, and metabolic disease among the geriatric population in Ansan City, a suburban area near Seoul, Korea. The nature and the basic procedures of the AGE study have been described in previous reports.567 Subjects who were aged below 60 years or whose Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores for cognitive impairment were below 24 were excluded. Sociodemographic variables including age, gender, marital status, level of education, and household income were collected.

All participants were fully informed about the purpose and methods of this study, and all of them gave their written informed consent. The study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Korea University Ansan Hospital Institutional Review Board.

This study was conducted by a well-trained survey team composed of three psychiatrists, one psychologist, and two research nurses. The survey team developed the Happiness Questionnaire (HQ), a semi-structured, open-ended survey form that asks 4 questions about happiness: 1) "What is your current happiness score on a 100-mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)? (Rate the score)"; 2) "When are you happiest? (Describe the situation)"; 3) "If you are not happy, why is this?"; and 4) "Which of the following is an essential condition for happiness? (Choose one): good health, economic stability or wealth, religious life, social honor, being with family, achievement, other." Each item of the HQ was designed through discussions among the survey team and an assistant statistician.

In addition, the HQ was designed as a preliminary screening questionnaire to measure the happiness levels of the elderly. That is, it was our intention to develop a preliminary scale [Happy (Haeng-Bok, 幸福) aging scale], the validity and reliability of which could be assessed in follow-up studies.

To explore the relationships between the level of happiness and symptoms of depression, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) also were administered.

The BDI is a questionnaire consisting of items answered on a 4-point Likert scale (0-3). It was developed to assess subjective symptoms and the respondent's degree of depression.8 It contains 21 questions concerning emotional, cognitive, motivational, physiological, and other symptoms of depression. It was verified to be reliable and valid for depression screening among elderly Korean individuals.5 Higher scores on the BDI reflect more severe depressive symptoms.9 In the present study, a score of 16 was used as the cutoff value for depression, following the validation study conducted in Korea.

The GDS was specifically designed to minimize the effects of the various physical symptoms of the elderly.10 It is composed of 30 dichotomous items about depression, and the total score ranges from 0 to 30, where higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms. In the present study, a score of 18 was used as the cutoff value for depression, following the validation study conducted in Korea.11

Data were summarized as means and standard deviations (SD) or frequencies. Intergroup comparisons were performed using Student's t-tests, analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and Chi-squared tests. Bonferroni post hoc analyses were applied when significant group differences were observed by ANOVA. Pearson's correlation tests were used to examine the relationships between continuous variables. The relationships between the level of happiness and symptoms of depression were evaluated by linear regression analysis. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A value of p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

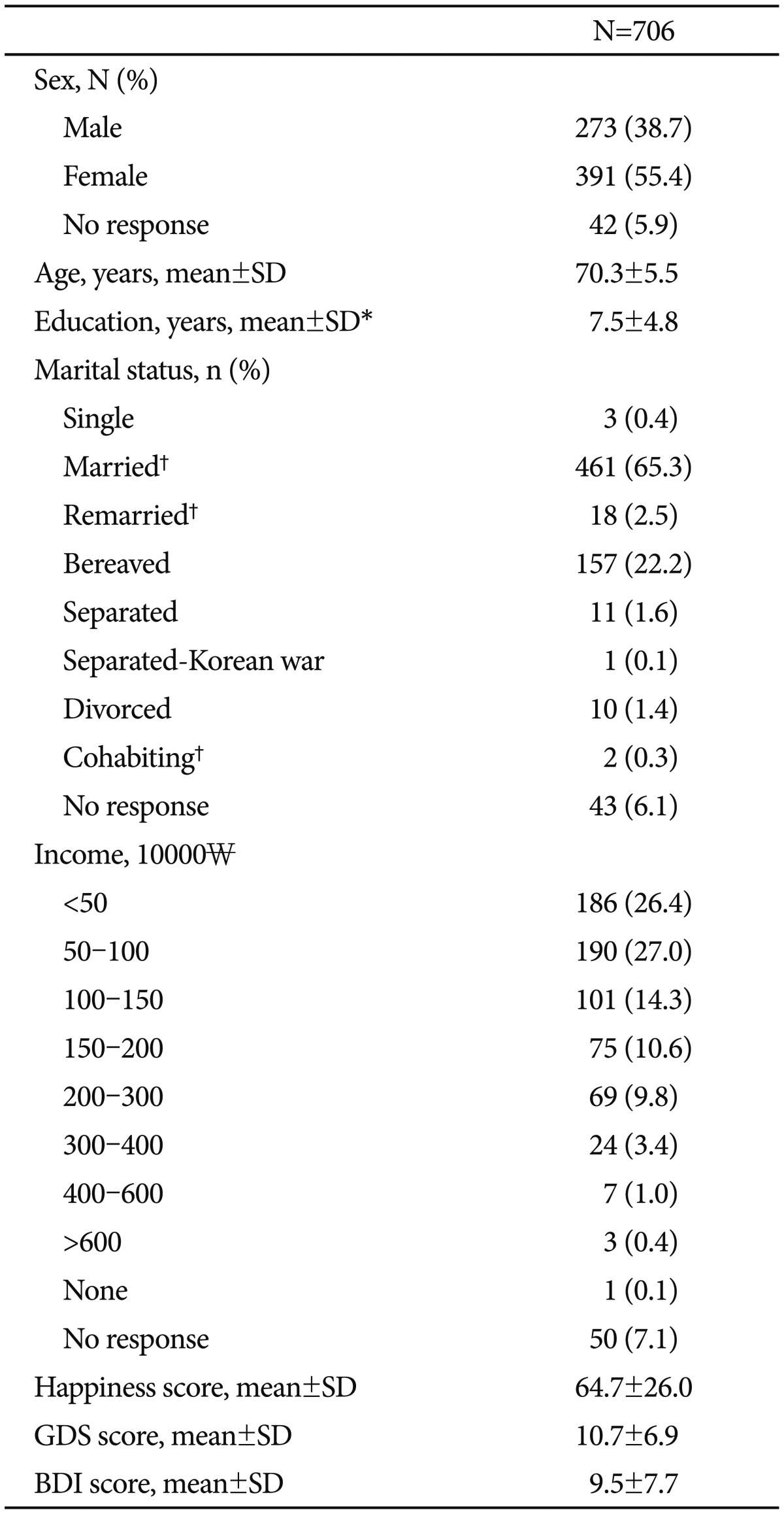

A total of 706 volunteers completed the survey. The mean age of this group was 70.3 (±5.5) years, with a range of 62 to 88 years. The mean scores of the VAS for happiness, GDS, and BDI were 64.7 (±26.0), 10.7 (±6.9), and 9.5 (±7.7), respectively. Sociodemographic data and scores on the scales are summarized in Table 1. The mean number of years of education completed by the respondents was 7.5 (±5.0). The overall educational backgrounds of the subjects were weakly cor-related with their happiness scores (Pearson's correlation coe-fficient r=0.2, p<0.01). A subsequent ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc analysis showed that subjects without any school education felt significantly less happiness (n=98, mean happiness score=55.2, SD=32.4) than high school graduates or dropouts (n=133, mean=69.7, SD=21.1), college or university graduates or dropouts (n=73, mean=71.7, SD=19.7), and those who had completed postgraduate education (n=11, mean=88.1, SD=8.3), as individual groups (all p<0.01). Both elementary school dropouts (n=242, mean=64.1, SD=26.8) and elementary school graduates (n=107, mean=63.6, SD=24.6) reported lower levels of happiness than the postgraduate and higher-education groups (all p<0.05). When the subjects were divided into two groups on the basis of whether they had partners, the mean happiness score of the group with partners (married, remarried, or cohabiting, n=481) was 66.6 (±24.5), significantly higher than that of the group without partners (single, bereaved, separated, or divorced, n=182, mean: 60.7±29.2) (t=2.413, df=283.075, p<0.05). Besides educational level and relationship status, no sociodemographic variables were significantly related to the happiness score.

The mean VAS score for happiness among the 706 volunteers was 64.7±26.0. One hundred sixty-eight subjects (23.8%) reported that they felt the greatest happiness when they got together with their family members, including grandchildren. Ninety-three subjects (13.2%) named times when they lived in peace with family members (well-being) as their happiest situations (Table 2).

A total of 128 subjects (18.1%) said that they never felt happy before. Among them, 115 subjects disclosed their reasons for not being happy at all; these included poor health conditions (n=33, 28.7%), economic problems of their own (n=19, 16.5%), and economic problems of their children (n=17, 14.8%), in order of frequency (Table 3).

The most frequent answer to the question of which condition is essential for happiness was good health (n=461, 65.3%). Others said that being with family (n=145, 20.5%) was an essential condition for happiness, followed in order of frequency by religious life (n=51, 7.2%) and financial security 5.8% (n=41) (Table 4).

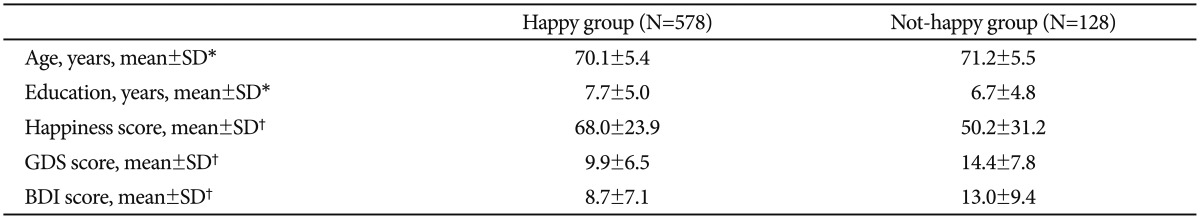

We classified the subjects into two groups: the happy group and the not-happy group. We used the term "not happy" because there are subtle differences in nuance between "unhappy" and "not happy". Subjects who responded regarding their happiest moments were classified as the happy group (n=578), and those who responded that they never felt happy at all were assigned to the not-happy group (n=128). The mean happiness score of the happy group was 68.0 (±23.9); this value was significantly higher than that of the not-happy group (50.2±31.2, p<0.01). The mean age was significantly younger and the level of education significantly higher in the happy group than in the not-happy group (Table 5).

The BDI and GDS scores were significantly lower in the happy group than in the not-happy group. In the happy group, 77 subjects (14.8%) were identified as having depression using the BDI (BDI score ≥16), and 83 subjects (15.6%) were identified as having depression by the GDS (GDS score ≥18). In the not-happy group, 36 subjects (32.1%) and 48 subjects (41.0%) were identified as having depression by the BDI and the GDS, respectively. The proportion of subjects who were considered to have depression was significantly higher in the not-happy group than in the happy group (chi-squared tests, p<0.01 for both BDI and GDS).

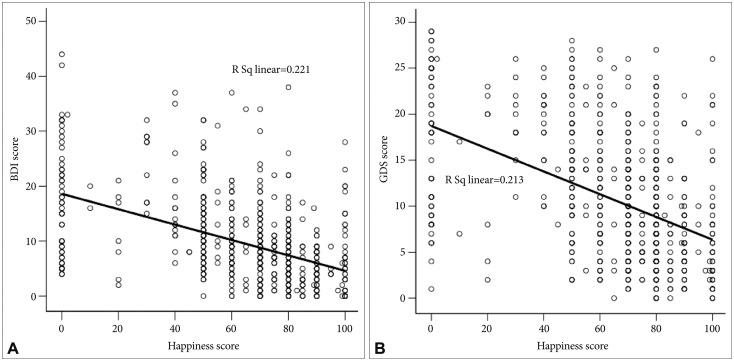

Subjects were then categorized according to their depression status on the basis of the BDI (score ≥16). The mean happiness scores of the depressive group (n=113) and the non-depressive group (n=519) were 43.3 (±30.2) and 70.1 (±22.3), respectively; this difference between the two groups was significant (t=-8.899, df=139.90, p<0.01). The results were similar when depression status was determined on the basis of the GDS (score≥18); the depressive group (n=131) had significantly lower happiness scores (44.8±29.9) than the non-depressive group (n=501, 70.3±22.0). Scores on the BDI and the GDS were negatively correlated with happiness scores; these findings reached statistical significance in linear regression analysis (both p<0.01) (Figure 1).

A preliminary scale [Happy (Haeng-Bok, 幸福) aging scale] (Supplement in the online-only Data Supplement) for measuring the happiness level of the elderly was developed based on the HQ, the preliminary screening questionnaire. The preliminary scale was designed by the same survey team and assistant statisticians who designed the HQ. The responses of 706 subjects to the two open-ended questions and the single closed-ended question in the HQ were categorized according to the characteristics and types of expressions, and arranged in order of frequency. Thirty-two responses had a frequency of 3 or more, and accordingly, 32 items were prepared. Of the 32 items, seven items that overlapped or were infrequently answered were excluded, and the remaining 25 items were included in the preliminary scale. The preliminary scale was composed of items with a score of 0-3: 0 for "Absolutely not," 1 for "No," 2 for "Yes," and 3 for "Absolutely yes." The scores of the two negative items were added inversely.

We investigated the perceived levels of happiness and the factors influencing happiness among the community-dwelling elderly in Korea. The mean VAS score, representing subjects' levels of happiness, was 64.74 (±26.25). In the present study, the mean age of the happy group was significantly lower than that of the not-happy group, but overall, age was not correlated with the happiness score. This may be a result of the fact that our study was limited to elderly individuals aged 62-88 years. Previous studies that covered all age groups reported a consistent degree of happiness across age groups.12 One study concluded that older people may have greater resilience derived from various past experiences or a stronger likelihood of engaging in religious activities than younger people.13 Further studies that include all age groups or use unified measures are needed.

Two sociodemographic variables, having a partner and a high level of education, were significantly associated with greater happiness scores in the present study. The subjects who had partners (married, remarried, or cohabiting) reported greater happiness than those who did not. A previous study also emphasized the importance of living with a partner, especially in old age, because it more strongly predicted happiness among older people than among younger people.12

Subjects without any school education or with fewer years of education (≤9 years) felt lower levels of happiness than subjects who completed more than 16 years of education, and there seemed to be an overall trend of more educated subjects being happier. When divided into happy and not-happy groups, the subjects belonging to the happy group had significantly higher levels of education than those who belonged to the not-happy group. Similar results have been reported in other studies,1415 and the educational level or qualifications may be associated with economic or mental resources useful for coping.

One remarkable finding of the present study was the association between family and the level of perceived happiness. The happiest personal situations for most individuals, in order of frequency, were "getting together with family members" and "living in peace with family members (well-being)." Moreover, 20.5% of subjects (n=145) chose "being with family" as the most essential condition for happiness, making it the second-most-frequent answer to the fourth question of the HQ. Additionally, the third-most-frequent reason for subjects not being happy was economic problems of their children (n=17, 14.8%).

Many Korean people, particularly the elderly, place a high value on family, a tendency that supposedly originated in Confucian culture. Until several decades ago, an extended family system was very common, and taking good care of one's parents and children and having good relationships with family members were thought to be virtues. In a large-family system with a Confucian culture, people are bothered when the close bond between family members is interrupted or filial duty is neglected. Therefore, in this culture, family may be an important factor associated with the perception of happiness. Moreover, considering that loneliness was the reason that 14.0% (n=16) of not-happy subjects were not happy, the importance of family is still more apparent.

Another important happiness-associated factor was economic status. Unlike family factors, economic aspects were mentioned less often as personal happiest conditions or essential conditions for happiness. However, subjects answered that their own economic problems or those of their children were leading causes of their not being happy, accounting for 31.3% (n=36) of such responses. This discrepancy could be explained by two factors: attitudes toward materialistic values and the concept of happiness. In Korea, the idea that money is all-important, or the expression of excessive interest in money, has been regarded as worldly or shameful according to the traditional system of values. Therefore, it is possible that subjects were reluctant to refer to money (economy) directly when they were asked about their personal happiest conditions or their opinions on essential conditions for happiness. However, when the question about subjects' reasons for not being happy was asked, many subjects revealed that they were troubled by economic matters. Therefore, we guessed that money played as important a role in happiness as family, although this was not overtly expressed by the subjects. In that sense, the HQ has strength, as it questions subjects about happiness from several angles with slightly different wordings, and because of this, the subjects cannot help disclosing their real-life situations or honest values. On the other hand, the concept of happiness varies depending on the cultural and social background of each country.41617 The word "happy" is not so familiar to Korean people, and some people regard it as too abstract and vague, as if it is connected only with goodness and beauty; further, the word is not spoken frequently in everyday life. Therefore, another possibility is that subjects were prone to focus on other factors than money when asked about happiness. Actually, the poverty rate among elderly Korean people is estimated to be at least 37.1%, based on the minimum cost of living from the Poverty Statistics Yearbook (2009); this is a very high rate compared with those of the other countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (20% overall in 2009). Such a social condition may ensure the contribution of economic matters to perceived levels of happiness.

A third important factor for happiness was health, which was the most frequent answer to 2 questions on the HQ, namely, reasons for not being happy and essential conditions for happiness. The strong role of health was not surprising: the more aged a person becomes, the more medical diseases he/she develops, so health problems may have an inseparable relationship with happiness among the elderly. Moreover, health issues could cause conflicts with caregivers or family members and increase economic burdens, so good health may be an absolutely indispensable component of the sense of happiness.

On the other hand, symptoms of depression were associated with happiness levels. The differences in happiness scores between the depressive group and the non-depressive group were significant. Moreover, in the not-happy group, the prevalence of probable depression according to the BDI or GDS was also significantly higher than that in the happy group. Moreover, the scores of the BDI or GDS were associated with happiness scores. It is known that happiness is closely connected to mental health; conversely, depressive disorder is known to affect quality of life (QOL) and negative emotion, which are linked to the perception of happiness.1819 Considering that in traditional Korean culture, suppression or internalization of one's emotions (like depression or not being happy) is considered a virtue, an exact assessment of the relationship between the happiness level and depression might not have been achi-eved. Further studies that take cultural background into consideration are needed in order to investigate the relationship between happiness and mental disorders like depression.

Of course, the condition of being happy does not merely mean the absence of depression, anxiety, and other mental health problems; rather it is associated with satisfaction with life as a whole and the frequency and intensity of the experience of joy.20 There are some differences in terms of which factors are associated with happiness according to endemic moral culture and social strata.21 According to a study from India, economic status has no relationship with happiness.22 In China, the elderly feel happy when they stay with their children.23 A report from Hong Kong suggested that economic problems and primary support groups are important factors involved with the promotion of happiness among the elderly, findings that are similar to our results.24

Our study has some limitations. First, subject sampling was not conducted by a nationwide, stratified method; instead, the study was limited to a small suburban area. In addition, elderly individuals who were institutionalized or could not move by themselves were excluded. Therefore, the findings of the present study may have been affected by the properties of the suburban area and might not represent all elderly people, and we need to be cautious not to make generalizations based on the findings of this study. In addition, certain aspects of Korean culture, like the vague concept of happiness among Koreans, negative views of materialist values, and Confucian backgrounds could have affected the results, as mentioned previously. Finally, recall bias cannot be excluded.

Despite these limitations, the present study has strengths in assessing the happiness status of the Korean elderly and the factors and perspectives associated with their happiness. We used the HQ, which contained 4 questions about happiness, each of which took a delicately different angle to avoid the influence of cultural backgrounds and personal attitudes. Good relationships with family, economic stability, and good health were the most important factors associated with perceived levels of happiness. Among objective variables, having a partner and having completed a higher level of education were related to greater feelings of happiness.

Most previous studies that measured happiness levels targeted the general adult population, especially middle-aged adults. However, elderly people have unique features of their own, and the factors in their happiness differ from those of the general adult population. Few tools for measuring the happiness level of the elderly population have been suggested, but further studies on the factors of their happiness are required, and a concrete scale for measuring such factors must be developed. The preliminary scale [Happy (Haeng-Bok, 幸福) aging scale] in this study may help establish such a measuring tool. Further studies on the validity and reliability of this scale may be needed in the future. Measurements of the happiness level of the elderly population may be used for assessment and treatment in the geriatric psychiatry field.

Mental health service providers and policy makers need to take more interest in non-illness conditions such as happiness. Promoting such conditions could be a step that prevents the development of diseases, and that could be one way to reduce the enormous social burden of the elderly population in this aging society. Further studies using nationwide samples are required.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120004).

Supplement Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at http://dx.doi.org/10.4306/pi.2016.13.1.50.

References

2. Kim JH, Ann JH, Kim MJ. Relationship between improvements of subjective well-being and depressive symptoms during acute treatment of schizophrenia with atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Pharm Ther 2011;36:172-178. PMID: 21366646.

3. Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Knapen J, Maurissen K, Raepsaet J, Deckx S, et al. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation on state anxiety and subjective well-being in people with schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2011;25:567-575. PMID: 21402653.

4. Sarvimaki A, Stenbock-Hult B. Quality of life in old age described as a sense of well-being, meaning and value. J Adv Nurs 2000;32:1025-1033. PMID: 11095244.

5. Jo SA, Park MH, Jo I, Ryu SH, Han C. Usefulness of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) in the Korean elderly population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007;22:218-223. PMID: 17044132.

6. Woo EK, Han C, Jo SA, Park MK, Kim S, Kim E, et al. Morbidity and related factors among elderly people in South Korea: results from the Ansan Geriatric (AGE) cohort study. BMC Public Health 2007;7:10PMID: 17241463.

7. Park MH, Jo SA, Jo I, Kim E, Eun SY, Han C, et al. No difference in stroke knowledge between Korean adherents to traditional and western medicine-the AGE study: an epidemiological study. BMC Public Health 2006;6:153PMID: 16772038.

8. Beck A. Depression: Clinical Experimental and Theoritical Aspects. New York: Harper & Row;; 1967.

9. Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1993.

10. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Huang V, Adey M, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982-1983;17:37-49. PMID: 7183759.

11. Jung IK, Kwak DI, Shin DK, Lee MS, Lee HS, Kim JY. A reliability and validity study of Geriatric Depression Scale. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc 1997;36:103-112.

12. Cooper C, Bebbington P, King M, Jenkins R, Farrell M, Brugha T, et al. Happiness across age groups: results from the 2007 National Psychiatric Morbidity Survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2011;26:608-614. PMID: 21480378.

13. Yohannes AM, Koenig HG, Baldwin RC, Connolly MJ. Health behaviour, depression and religiosity in older patients admitted to intermediate care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2008;23:735-740. PMID: 18188870.

14. Kubzansky LD, Berkman LF, Glass TA, Seeman TE. Is educational attainment associated with shared determinants of health in the elderly? Findings from the MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Psychosom Med 1998;60:578-585. PMID: 9773761.

15. Murrell SA, Salsman NL, Meeks S. Educational attainment, positive psychological mediators, and resources for health and vitality in older adults. J Aging Health 2003;15:591-615. PMID: 14587528.

16. Prieto-Flores ME, Fernandez-Mayoralas G, Rosenberg MW, Rojo-Perez F. Identifying connections between the subjective experience of health and quality of life in old age. Qual Health Res 2010;20:1491-1499. PMID: 20562252.

17. Breeze E, Jones DA, Wilkinson P, Latif AM, Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher AE. Association of quality of life in old age in Britain with socioeconomic position: baseline data from a randomised controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:667-673. PMID: 15252069.

18. Abbas Asghar-Ali A, Braun UK. Depression in geriatric patients. Minerva Med 2009;100:105-113. PMID: 19277008.

19. Cohn MA, Fredrickson BL, Brown SL, Mikels JA, Conway AM. Happiness unpacked: positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion 2009;9:361-368. PMID: 19485613.

20. Argyle M. The Social Psychology of Everyday Life. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillian; 2010.

21. Barua A, Ghosh MK, Kar N, Basilio MA. Socio-demographic factors of geriatric depression. Indian J Psychol Med 2010;32:87-92. PMID: 21716860.

22. Linssen R, van Kempen L, Kraaykamp G. Subjective well-being in rural India: the curse of conspicuous consumption. Soc Indic Res 2011;101:57-72. PMID: 21423323.

23. Deng J, Hu J, Wu W, Dong B, Wu H. Subjective well-being, social support, and age-related functioning among the very old in China. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:697-703. PMID: 20033902.

24. Lam CW, Boey KW. The psychological well-being of the Chinese elderly living in old urban areas of Hong Kong: a social perspective. Aging Ment Health 2005;9:162-166. PMID: 15804634.

Figure 1

Scores on the BDI and the GDS were negatively correlated with happiness scores; these findings reached statistical significance in linear regression analysis (both p<0.01). A: Linear regression between happiness scores on the HQ and BDI scores. B: Linear regression between happiness scores on the HQ and GDS scores. HQ: Happiness Questionnaire, BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale.

Table 1

Sociodemographic data and BDI and GDS scores

1 U.S. dollar=1,055 Korean won at the time of the interviews. *significant correlation with the happiness score, Pearson correlation coefficient r=0.2, p<0.01, †subjects who had a partner (married, remarried, or cohabiting) showed significantly higher happiness scores than subjects who did not by a Student's t-test (t=2.413, df=283.075, p<0.05). BDI: Beck Depression Inventory, GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale, SD: standard deviation