|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 14(2); 2017 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

We assessed the cumulative conversion rates (CCR) from minor cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia among individuals who failed to participate in annual screening for dementia. Additionally, we analyzed the reasons for failing to receive follow-up screening in order to develop better strategies for improving follow-up screening rates.

Methods

We contacted MCI patients who had not visited the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia for annual screening during the year following their registration. We compared the CCR from MCI to dementia in the following two groups: subjects registered as having MCI in the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia database and subjects who failed to revisit the center, but who participated in a screening test for dementia after being contacted. The latter participants completed a questionnaire asking reasons for not previously visiting for follow-up screening.

Results

The final diagnoses of the 188 subjects who revisited the center only after contact were 19.1% normal, 64.9% MCI and 16.0% dementia. The final diagnoses of the 449 subjects in the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia database were 25.6% normal, 46.1% MCI and 28.3% dementia. The CCR of the revisit-after-contact group was much lower than anticipated. The leading cause for noncompliance was ŌĆ£no need for testsŌĆØ at 28.2%, followed by ŌĆ£other reasonsŌĆØ at 23.9%, and ŌĆ£I forgot the appointment dateŌĆØ at 19.7%.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) features evidence of subjective or objective cognitive impairment along with preservation of activities of daily living (ADLs).1 The preservation of ADLs is the core difference between MCI and dementia,2 and MCI is seen as a transition period or the middle state between normal cognition and dementia.3 Although most MCI patients' cognitive function remains stable over time, some patients exhibit functional decline due to cognitive deterioration, and 5-10% progress to dementia,4 which is a 4-10-fold higher rate of dementia progression than among the normal elderly.5 Most dementia patients are diagnosed in the moderate to severe stages rather than in the early stage of the disease.6 Therefore, in the aging population, detecting cognitive decline in the early stage via regular screening tests may provide an opportunity for patients to receive early treatment resulting in better outcomes and lower morbidity rates.6

Seoul is successfully dealing with dementia by establishing a community-integrated management system for dementia comprising a metropolitan center and 25 centers in the boroughs. Since they began providing social services in 2007, they have continued to do screening and publicity to broaden awareness of dementia. The tools used for early detection of dementia in Korea are the mini mental state examination in the Korean version of the CERAD assessment packet (MMSE-KC), Korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) and mini-mental state examination for dementia screening (MMSE-DS) for screening and the Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease neuropsychological test battery (CERAD-NP-K) or Seoul Neuropsychological Screening Battery (SNSB) for a thorough workup. Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia, where the authors currently work, uses the MMSE-KC as a screening tool and CERAD-NP-K for close examination. The center screens individuals aged 65 years and older, a total of approximately 7,000 subjects every year. Those whose MMSE-KC results indicate cognitive impairment go through an additional close examination. Once diagnosed with MCI, individuals are categorized into the high-risk group and registered in the database to receive an annual follow-up examination. Any individual suspected of having dementia is referred to a nearby general hospital for diagnosis and to confirm the cause. Over the past 3 years at the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia, the number of individuals undergoing screening was 20,833, and based on the results, 12% were suspected of having cognitive impairment underwent additional examination, and 13% were finally diagnosed with dementia. In other words, based on the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia database cross-sectional assessment at April 2015, approximately 5% of the screened subjects were considered to have MCI, and 6% were diagnosed with dementia.

However, some subjects failed to visit the Center for Dementia regularly for annual screening tests. The question arose as to whether subjects who did not visit the center for annual screening were different from those who came on their appointed dates. We noticed that some subjects who were screened behindhand were diagnosed with dementia. If the conversion rate of these subjects was lower than that of those who were regularly screened, this would mean they had lower early dementia detection rates, and thus, more attention is needed for these individuals. To our knowledge, there have been no previous domestic or foreign reports on factors related to follow-up attrition for dementia screening. Therefore, with the aim of heightening the quality of the dementia management and thereby slowing and ameliorating progression toward dementia, we investigated the reasons for follow-up loss in the MCI group and analyzed their demographic factors. Through this work, we intend to provide evidence to be used to reduce follow-up loss in those at risk for dementia.

Based on Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia's database, we examined MCI subjects who were categorized and registered as being in the high risk group from January 2008 to December 2012. The subjects of this study included the group who did and the group who did not visit the center at the intended one-year follow-up date.

The total number of subjects who were personally contacted was 834. Only 48 subjects revisited within 1 year, and the other 786 subjects did not visit the center for annual screening. Among the 786 subjects, 188 revisited the center after being personally contacted. Forty-eight of those who visited within 1 year without further contact were grouped with the 188 revisiting subjects to form the follow-up group, and 598 subjects who did not visit the center despite personal contact were grouped to form the follow-up loss group (Figure 1).

Within the same period, the total number of registered MCI subjects was 868. Since this number includes subjects who died or moved to other areas, it differs from the number of subjects who were personally contacted. Among these subjects, 449 had revisited the center more than once for screening. In order to roughly weigh the effect of strict screening, we indirectly compared the final diagnosis of the following two groups; 188 subjects who revisited the center after personal contact, and 449 subjects who were previously registered in the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia's database as revisited the center.

Mental health nurses and social workers at the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia screened people aged 65 years and over using the MMSE-KC. Each individual whose screening results indicated suspicion of cognitive impairment visited the Center for Dementia and underwent a thorough workup by a psychiatrist employing the CERAD-NP-K and psychiatric assessment, leading to a diagnosis of normal, MCI or dementia based on the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria. The MCI subjects were categorized as being in the high-risk group and were instructed to return for annual screening.

In the high-risk group of subjects registered from January 2008 to December 2012, those who did not visit the center within 1 year were personally contacted by phone or visit. The subjects were asked to revisit the center and so that assessment with the CERAD-NP-K could be done. During the same period of time, we identified the high-risk subjects registered in the database who had had more than one annual screening test and confirmed their final diagnoses. We then calculated the cumulative conversion rate of those who revisited the center after contact and the cumulative conversion rate of all registered subjects who revisited the center more than once. Since direct comparison of the two groups is statistically impossible, we intended to compare the rough tendency of the final diagnosis of each group.

We used a questionnaire to ask the subjects who revisited the center after being contacted about their reasons for not having visited at the intended time. We also analyzed their general characteristics from the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia database, such as gender, age, occupation, and underlying diseases.

The CERAD is a standardized clinical neuropsychological tool developed by Morris et al. in 1989 to assess for Alzheimer's disease. The CERAD was developed to establish uniformity in registration standards and assessment methods for Alzheimer's disease patients. The CERARD's high accuracy in clinical assessment for Alzheimer's disease diagnosis has been confirmed by neuropathological findings.7 The CERAD assessment tool is used in various clinical and research settings, and along with neuropathological and neuroimaging assessments, it can be used to assess behavioral symptoms of dementia patients. Lee et al.8 translated and revised the CERAD in 2002 to develop the Korean version (CERAD-NP-K) and verified its reliability and validity.

Lee et al.8 also translated and adapted the MMSE included in the English version of the CERAD and verified its reliability and validity. In addition to adapting the questions, methods and scoring system of the CERAD-MMSE for the MMSE-KC, some additional items were included in the MMSE-K that had been used for a long time in Korea. In the study by Lee et al.8 of normal standards for Korean elderly, they developed a normal standards table in accordance with education and age, which they verified to have excellent validity.

Health professionals from Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia, composed of psychiatrists, mental health nurses and social workers, held meetings and created potential items for the questionnaire about difficulties for screening, based on their experience. We incorporated the opinions and selectively configured the questionnaire. In the questionnaire, subjects were asked to choose the one item closest to the reason why they could not return for screening.

The following are the choices given in the questionnaire:

1) deceased, 2) moved, 3) no need for checkup, 4) negative awareness of dementia, 5) the test is unreliable, 6) too difficult to come, 7) due to medical conditions, 8) difficulty walking, 9) currently hospitalized, 10) too busy, 11) forgot the date, and 12) other.

The 188 subjects who revisited the center after contact were diagnosed as follows: 19.1% (36) as normal, 64.9% (122) with MCI, and 16.0% (30) with dementia. During the same period, MCI subjects registered in the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia's database were diagnosed as follows: 25.6% as normal, 46.1% with MCI, and 28.3% with dementia (Table 1, Figure 2).

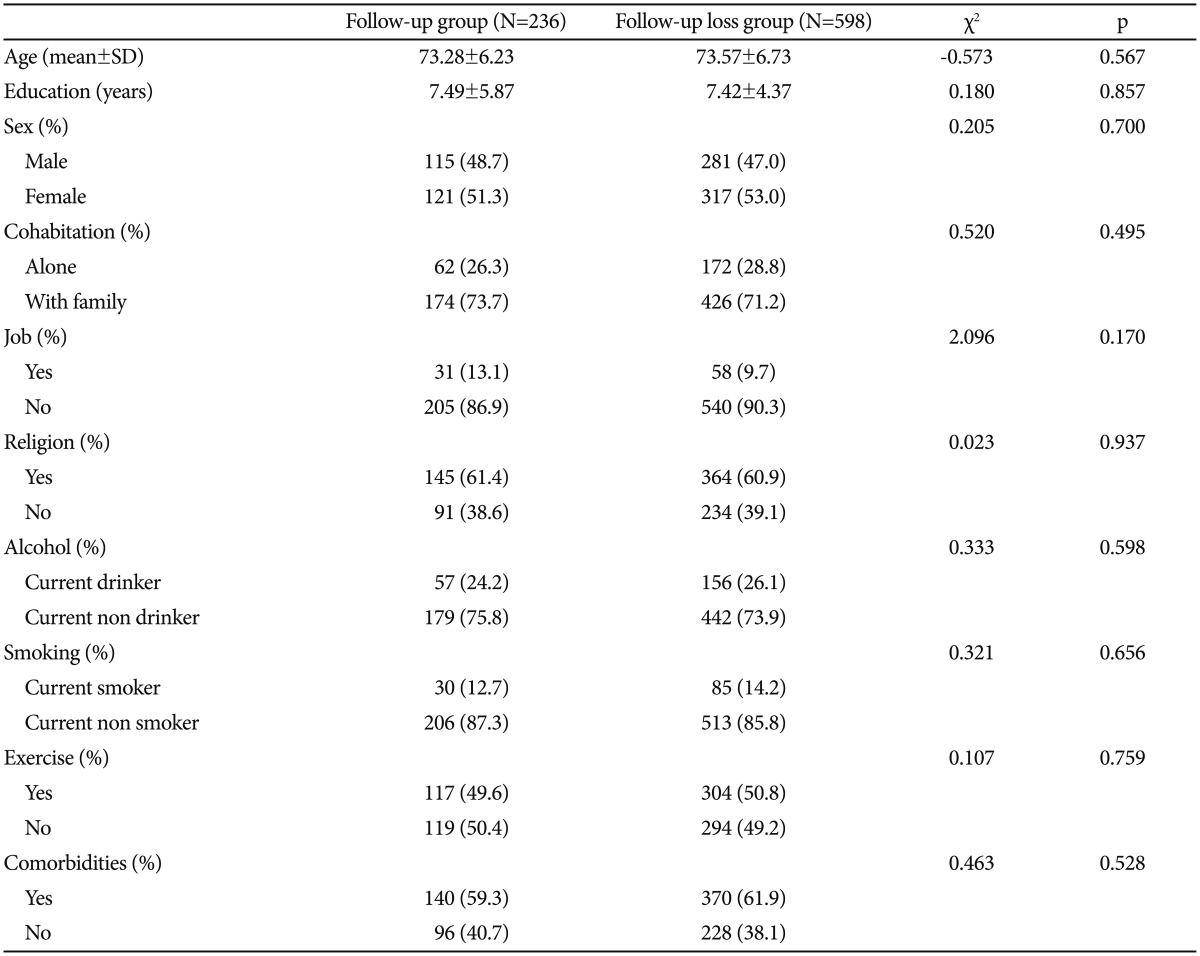

Among the 786 individuals who did not revisit the center within 1 year, 188 revisited the center and completed the questionnaire after being contacted, and 598 refused to visit or could not be reached. Among the reasons for not revisiting the center, item 3 ŌĆ£no need for checkupŌĆØ was most frequently given at 28.2%, followed by item 12 ŌĆ£otherŌĆØ at 23.9% and item 11 ŌĆ£forgot the dateŌĆØ at 19.7%. The 45 subjects who answered ŌĆ£otherŌĆØ further reported the following reasons: 9 responded ŌĆ£there was no call from the center,ŌĆØ 3 responded ŌĆ£I was too busy,ŌĆØ 2 responded ŌĆ£I didn't know I had to take a test,ŌĆØ 1 responded ŌĆ£personal reasons,ŌĆØ and 29 left the reason blank (Figure 3).

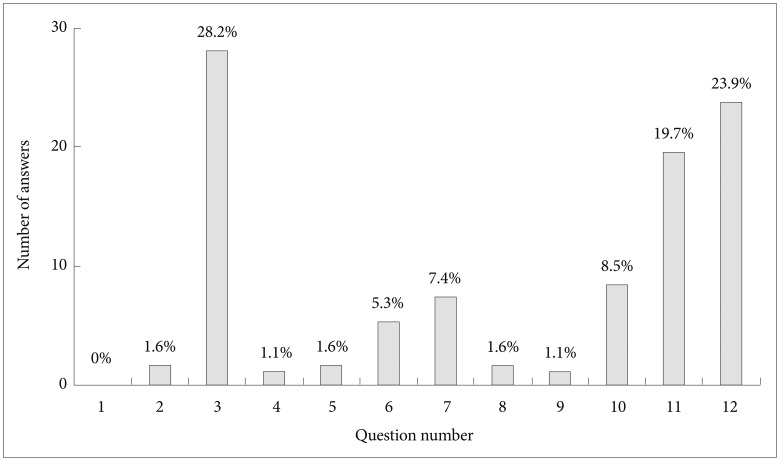

The demographic characteristics are listed as Table 2. The follow-up group was composed of 236 subjects, and the follow-up loss group was composed of 598 subjects. There were no statistical differences in demographic characteristics, such as gender, co-residents, occupation, religion, alcohol, smoking and exercise. The average years of education for the follow-up group was 7.49┬▒5.87, and for the follow-up loss group it was 7.42┬▒4.37; these values were not significantly different (t=0.180, p=0.857) (Table 2).

The final diagnoses of those who revisited the center after personal contact were as follows: 19.1%, normal; 64.9%, MCI; and 16.0%, dementia. In contrast, of the 24,899 subjects in the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia's database who were screened from January 2008 to December 2012, 28.3% transitioned from MCI to dementia. This indicates that the follow-up loss group had a lower dementia diagnosis rate than the community-based population. Although there are limitations that the results were not statistically compared, lower dementia diagnosis dementia diagnosis rates than the community may suggest the importance of regular annual screening. In other words, compared with the follow-up group, there is a possibility that the follow-up loss group had a lower chance of detecting dementia due to lack of education of dementia, lack of regular check-up by family and friends. These findings may suggest that we need to extend outreach and education efforts regarding dementia for this population. In a study of the progression of cognitive impairment conducted in the United States, 56% of the MCI patients were stable without any further cognitive decline, 8% improved to become normal, and 35% progressed to dementia.9 These results suggest higher detection rates compared to our study, which seems to be related to our study's retrospective design for examining the diagnoses as well as the poor understanding and awareness of dementia in the studied population.

In the personal contacting of the 786 subjects who had not revisited the center within one year, 598 (76.1%) reported a negative response to the center's screening test. In many cases, even after numerous calls, subjects hung up the phone, and many of the subjects expected the center to prescribe medication for dementia or perform neuroimaging tests. Through the negative response of the receivers, we could indirectly suppose a lack of understanding of the disease's course and the purpose of dementia screening.

The most commonly selected questionnaire reasons for follow-up loss was ŌĆ£no need for checkup,ŌĆØ accounting for 28.2% of the answers. The core features of MCI diagnosis are 1) subjective cognitive impairment, 2) objective cognitive impairment, and 3) function preservation of activities of daily living (ADLs).10 Since subjective and objective cognitive impairment can be seen in both MCI and dementia patients, function preservation of ADLs is the main standard for differential diagnosis.211 We may assume that MCI patients with preserved function may have had no difficulties during their everyday lives and thus had no need for reexamination. It has been reported that the public interest in dementia is high, although understanding of dementia is relatively low.12 This suggests that a poor understanding of the course of MCI may result in failure to appreciate the importance of regular screening.

The next-most common answer, ŌĆ£no need for checkup,ŌĆØ may be related to poor insight. Decreased awareness of memory impairment is often seen in Alzheimer's dementia and in MCI.13 Along with memory impairment, which is the main symptom of MCI patients, lacking self-awareness or ŌĆ£loss of selfŌĆØ is reported to be similar in MCI and dementia patients.14 Therefore, there is a possibility that subjects with cognitive impairment may have felt no need for checkup due to poor insight.

For the third-most frequent answer, ŌĆ£forgot the date,ŌĆØ we can consider the possibility of amnestic MCI. In a study of 296 MCI subjects, the incidence rate of the amnestic type of MCI (37.7 per 1,000 person-years) was higher than that of non-amnestic MCI (14.7 per 1,000 person-years).15 Although the current study did not distinguish MCI according to subtypes, reports that the amnestic type has a higher proportion suggest that some MCI subjects forgot to visit the center due to memory impairment.

Given prior studies suggesting that it is not subjective memory impairment, but rather the informant's report that influences progression to dementia,16 educating care-providers along with MCI patients is important. A longitudinal study of 534 subjects who were older than 70 years in age reported that, during the follow-up period, among the 38% of MCI patients whose diagnosis changed to normal, 65% were later diagnosed with MCI or dementia. It has been reported that the diagnosis of MCI is an important factor for prognosis assessment regardless of when it is diagnosed, which further supports the importance of regular screening.17

There was no statistical difference in demographic characteristics between the follow-up group who revisited the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia and the follow-up loss group. This indicates that the follow-up response difference is not caused by demographic characteristics, but rather by awareness of dementia and characteristics of the disease itself.

Those who fail to attend regular follow-up visits have a lower likelihood of early diagnosis of dementia, meaning more intensive management is needed. We believe that reasons for follow-up loss may be crucial for intensive management for MCI patients, and the biggest reason reported in this study is lack of knowledge. To increase our understanding of dementia, the National Central Dementia Center has been established, and active publicity via various media is continuous. For the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia, various education and publicity materials and programs have been created, and distributed and carried out by volunteers. Education materials for dementia need to be developed and continuously provided for elder people, caregivers and the general public. Considering the characteristics of MCI and dementia, the role of the caregiver is crucial. Therefore, along with active publicity, detailed education about the disease is important. Also, to publicize the importance of early screening, contact possible MCI subjects, and recruit them to participate in cognitive rehabilitation programs, the biggest challenges are securing the needed personnel and budget. These are required for the development of dementia support services.

A limitation of this study is that the response rate regarding ŌĆ£reasons for not visitingŌĆØ was only 23.9% (188). Because 76.1% (598) refused to revisit the center when contacted, we note that the investigation of their reasons for not visiting is difficult, because the results may not represent the follow-up loss group as a whole. Similarly, because 23.9% of the subjects answered ŌĆ£other,ŌĆØ the results may not fully reflect the reasons for not visiting the center. Also, because this is a single center study, the results may not be a good representation of the target population. However, as the first study to investigate various reasons for not visiting the center for regular screening, this study makes useful contributions to the field of dementia diagnosis and management.

References

1. Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, et al. Mild cognitive impairment-beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med 2004;256:240-246. PMID: 15324367.

2. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CR Jr, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:263-269. PMID: 21514250.

3. Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 1999;56:303-308. PMID: 10190820.

4. Mitchell AJ, Shiri-Feshki M. Rate of progression of mild cognitive impairment to dementia--meta-analysis of 41 robust inception cohort studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;119:252-265. PMID: 19236314.

5. Petersen RC, Stevens J, Ganguli M, Tangalos E, Cummings J, DeKosky S. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001;56:1133-1142. PMID: 11342677.

6. Lin JS, O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Perdue LA, Burda BU, Thompson M, et al. Screening for Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults: An Evidence Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2013,11;Report No.: 14-05198-EF-1.

7. Gearing M, Mirra S, Hedreen J, Sumi S, Hansen L, Heyman A. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part X. Neuropathology confirmation of the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1995;45:461-466. PMID: 7898697.

8. Lee JH, Lee KU, Lee DY, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim JH, et al. Development of the Korean Version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Packet (CERAD-K): clinical and neuropsychological assessment batteries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57:P47-P53. PMID: 11773223.

9. Aretouli E, Tsilidis KK, Brandt J. Four-year outcome of mild cognitive impairment: the contribution of executive dysfunction. Neuropsychology 2013;27:95-106. PMID: 23106114.

10. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256:183-194. PMID: 15324362.

11. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:270-279. PMID: 21514249.

12. Kim H, Park K, Kim S. Survey of dementia awareness and needs in Seongdong-gu regional center for dementia. Dement Neurocogn Disord 2008;7:52-63.

13. Vogel A, Stokholm J, Gade A, Andersen BB, Hejl AM, Waldemar G. Awareness of deficits in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease: do MCI patients have impaired insight? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2004;17:181-187. PMID: 14739542.

14. Vogel A, Hasselbalch SG, Gade A, Ziebell M, Waldemar G. Cognitive and functional neuroimaging correlate for anosognosia in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2005;20:238-246. PMID: 15717342.

15. Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, et al. The incidence of MCI differs by subtype and is higher in men The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology 2012;78:342-351. PMID: 22282647.

16. Tierney MC, Szalai JP, Snow WG, Fisher RH. The prediction of Alzheimer disease: the role of patient and informant perceptions of cognitive deficits. Arch Neurol 1996;53:423-427. PMID: 8624217.

17. Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Christianson TJ, et al. Higher risk of progression to dementia in mild cognitive impairment cases who revert to normal. Neurology 2014;82:317-325. PMID: 24353333.

Figure┬Ā1

Study design and participant flow. MCI: mild cognitive impairment, MMSE-KC: Mini Mental State Examination in the Korean version of CERAD, CERAD-NP-K: Korean version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease neuropsychological test battery.

Figure┬Ā2

Final diagnosis comparison between the Dongdaemun-gu Center for Dementia database and the revisit-after-contact group. MCI: mild cognitive impairment.

Figure┬Ā3

Reported reasons for follow up loss (%). Question number: 1 deceased, 2 moved, 3 no need for checkup, 4 negative awareness of dementia, 5 the test is unreliable, 6 too difficult to come, 7 due to medical conditions, 8 difficulty walking, 9 currently hospitalized, 10 too busy, 11 forgot the date, 12 other.