|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 14(2); 2017 > Article |

Abstract

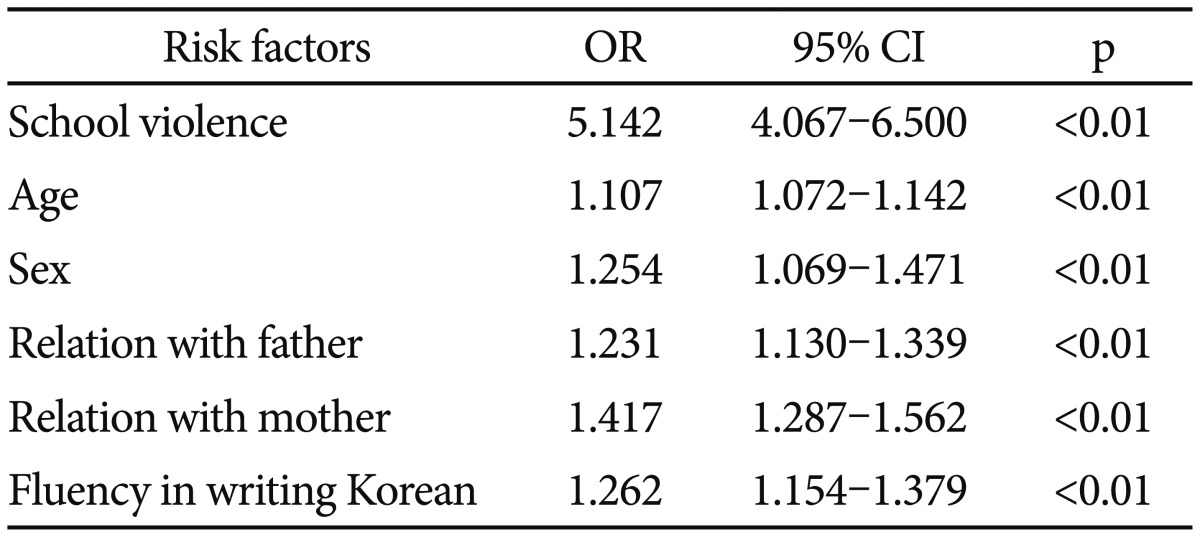

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of school violence on depressive symptoms among the offspring of multicultural families in South Korea. Data from the National Survey of Multicultural Families 2012, conducted by the Korean Women's Development Institute and Statistics Korea, were used in this study. Complex samples logistic regression was performed to determine the effect of school violence on depressive mood. The survey participants were 3999 students between the ages of 9 and 24. Of the participants, 22.1% reported experiencing depressive symptoms and 9.1% reported experiencing school violence within the last year. School violence was a strong risk factor (OR=5.142, 95% CI=4.067-6.500) for depressive symptoms after adjusting for personal, familial and school factors. School violence is a serious contributor to depressive mood among the offspring of multicultural families. There is a significant need to monitor school violence among this vulnerable group.

School violence is a serious social problem. Ensuring a safe school environment free from violence has been a major policy agenda for educational reforms, and many countries have struggled to address school violence.1 In school violence, victimization can take various forms, including physical, verbal, relational and cyber-bullying.2 It is evident that the consequences of school violence are serious and life-long: victims often suffer from lower self-esteem, chronic absenteeism, school avoidance, feeling unsafe and insecure in the school setting, decreased educational progress and success, and, in rare cases, even suicide.3 Although the factors determining the profile of victims of violence are complex, they tend to be associated with inequalities linked to socio-economic status, race, ethnicity, gender and sexual orientation.4 Therefore, children who are immigrants or the offspring of immigrants can be vulnerable to school violence.

The number of immigrants has been rapidly increasing in South Korea as the number of international marriages has increased.5 However, the social systems and cultural environment of Korea are not yet mature enough to respond constructively to this cultural diversity because Korea has been an ethnically homogenous country for thousands of years.6 The mental health of immigrants has become a major issue in South Korea because a report was published stating that immigrant women have higher levels of anxiety and their children also have more internalizing and externalizing symptoms than children of native parents.7 Although school violence can seriously affect adjustment and mental health in children and adolescents, there are few studies about school violence among the offspring of immigrants in South Korea. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of school violence on depressive symptoms among the offspring of multicultural families in South Korea.

We used data from the 2012 National Survey of Multicultural Families (NSMF), which was conducted by the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family to fulfill the requirements of the Multicultural Family Support Act of 2008. The target households of the NSMF were identified by obtaining addresses and basic demographic information from the records of the Ministry of Public Administration and Security. A total of 4775 offspring were eligible to participate in this survey. Trained interviewers visited each of the target households and collected survey data from immigrants and their offspring using a self-administered questionnaire. After excluding surveys with missing data, 3999 offspring were included in the secondary data analysis. Ethical approval was not required for this secondary data analysis because the 2012 NSMF data does not include any personal information and can be accessed easily for public purposes.

Basic demographic data were collected, including age, sex, level of relationship with father and mother and Korean language fluency. Participants were asked about their past experiences of school violence, which included all types of violence that can occur in school: verbal assault, bullying, being forced to run errands, robbery, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and cyber-bullying. Depressive mood was assessed based on responses to the question, ŌĆ£In the past 12 months, have you experienced sadness or despair that significantly influenced your everyday life for two weeks?ŌĆØ An answer of yes or no to these two questions was coded.

In the 2012 NSMF, adjusted weights were applied to the data to obtain a representative sample of the Korean population. A logistic regression was used to determine the relationship between school violence and depressive mood by adjusting for confounding factors such as personal, school, and family factors. The collected data were analyzed using PASW Statistics version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

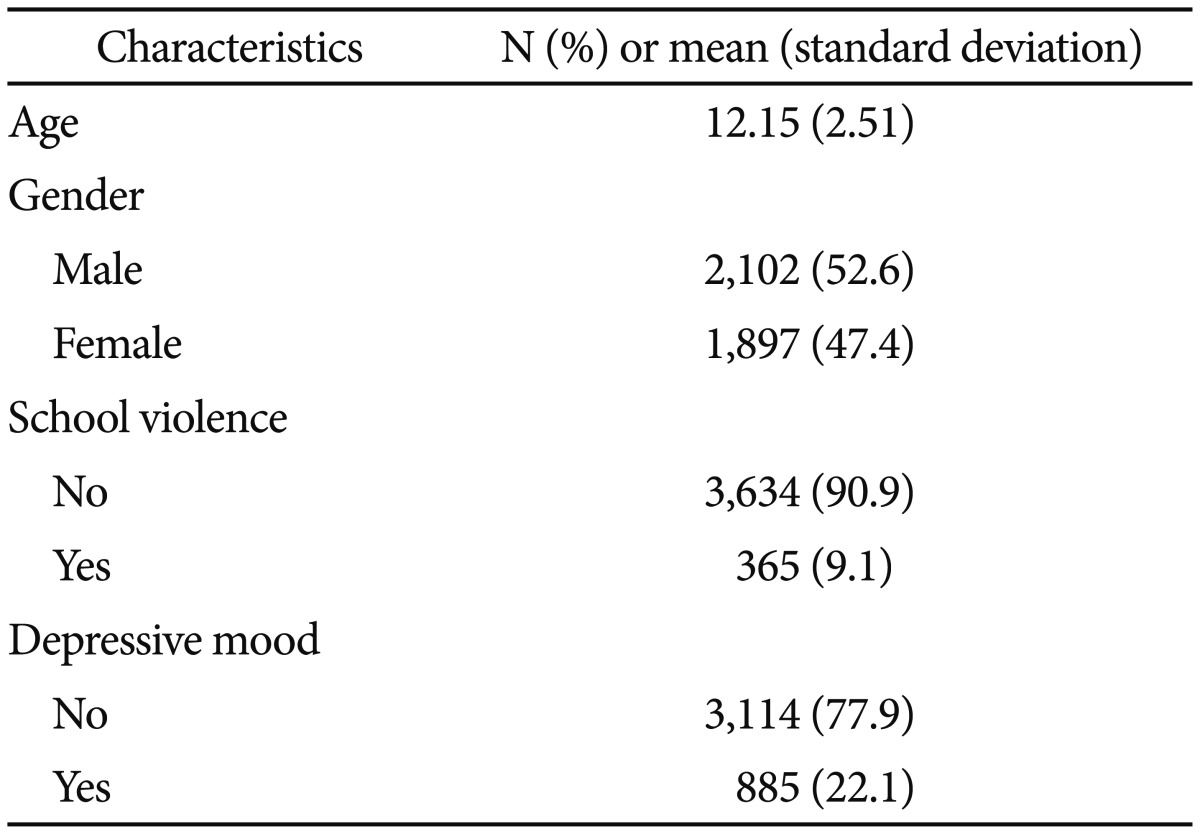

A total of 3999 offspring participated in this secondary data analysis. The basic demographic data is shown in Table 1. The likelihood that a student would report having experienced school violence increased (OR=5.142, 95% CI 4.067-6.500, p<0.01) after adjusting for age, sex, relation with parents and fluency in Korean language (Table 2).

The aims of the study were to examine the association between school violence and depressive mood among the offspring of immigrants living in South Korea. Though complex causes and moderating factors could contribute to the findings, acculturation stress might be a unique pathway to bullying victimization for immigrant youths. Acculturation is the process of adjusting to a different culture through changes in attitudes, behaviors, and identifications as immigrants encounter the culture of the host country.8 Youths who experience acculturation stress might exhibit characteristics that are associated with heightened risk of victimization, such as social isolation, anxiety, insecurity, and cautiousness.9 There is a high possibility that immigrants and their offspring might suffer more serious acculturation stress in South Korea, which has long had a relatively homogenous population and because the economic crisis, has had a competitive atmosphere.

Though this study did not compare immigrant youth and Korean native youth, the few existing studies on bullying among immigrant youths yield conflicting evidence about their risk of victimization relative to native youths. Some studies have found that relative to the native born, the foreign born are just as likely10 or less likely11 to be victims. Other research suggests that the negative mental and physical health effects of victimization are stronger among the foreign born than the native born.12 Regardless of whether immigrant youths are more at risk than natives, immigrant youths experience school violence and its negative consequences, including depressive mood. Our results are similar to those of previous papers, suggesting that immigrant youths need more multilevel supportŌĆöfrom the individual level to the community levelŌĆöto address problems from the biologic level of depression to cultural issues associated with the acculturation process.

This study has several limitations. First, we used a self-report scale with simple questions to measure depressive mood and school violence; therefore, the interpretation of the results may be limited. Second, the cross-sectional nature of the survey limits the testing of causal paths. Despite these limitations, the results of this study can be generalized to the offspring of multicultural families due to the use of nationally representative data. When the next wave of data is released for this dataset, it will be possible to perform a longitudinal analysis or trend analysis of the relationship between school violence and depressive mood.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the Korea Mental Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (HM15C1058).

References

1. Akiba M. Predictors of students fear of school violence: a comparative study of eight graders in 33 countries. Sch Eff Sch Improv 2008;19:51-72.

2. Espelage DL, Swearer SM. Bullying in North American Schools: A Social-Ecological Perspective on Prevention and Intervention. 2nd. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010.

3. Esbensen FA, Carson DC. Consequences of being bullied: results from a longitudinal assessment of bullying victimization in a multisite sample of American students. Youth Soc 2009;41:209-233.

4. Peguero AA. School, bullying, and inequality intersecting factors and complexities with the stratification of youth victimization at school. Sociol Compass 2012;6:402-412.

5. Kim HS. Social integration and heath policy Issues for international marriage migrant women in South Korea. Public Health Nurs 2010;27:561-570. PMID: 21087310.

6. Sung M, Chin M, Lee J, Lee S. Ethnic variations in factors contributing to the life satisfaction of migrant wives in South Korea. Fam Relat 2013;62:226-240.

7. Lee SH, Park YC, Hwang J, Im JJ, Ahn D. Mental health of intermarried immigrant women and their children in South Korea. J Immigr Minor Health 2014;16:77-85. PMID: 23184349.

8. Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am Psychol 2010;65:237-251. PMID: 20455618.

9. Aluede O, Adeleke F, Omoike D, Afen-Akpaida J. A review of the extent, nature, characteristics and effects of bullying behaviour in schools. J Instr Psychol 2008;35:151-158.

10. Del Barrio C, Mart├Łn E, Montero I, Guti├®rrez H, Barrios A, De Dios MJ. Bullying and social exclusion in Spanish secondary schools: national trends from 1999 to 2006. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2008;8:657-677.

11. Strohmeier D, Spiel C. Immigrant children in Austria: aggressive behavior and friendship patterns in multicultural school classes. J Appl Sch Psychol 2003;19:99-116.

12. Abada T, Hou F, Ram B. The effects of harassment and victimization on self-rated health and mental health among Canadian adolescents. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:557-567. PMID: 18538456.