|

|

- Search

| Psychiatry Investig > Volume 14(3); 2017 > Article |

Abstract

Objective

People often evaluate others using fragmentary but meaningful personal information in recent days through social media. It is not clear that whether this process is implicit or explicit and what kind of information is more important in such process.We examined the effects of several meaningful fragmentary information onattitude.

Methods

Thirty three KAIST students were provided four fragmentary information about four virtual people that are meaningful in evaluating people and frequently seen in real life situations, and were asked to imagine that person during four follow-up sessions. Explicit and Implicit attitudes were measured using Likert scale and Implicit Association Test respectively. Also, eye tracking was done to find out the most important information.

Results

Strong explicit attitudes, were formed toward both men and women, and weak but significant implicit attitudes, were generated toward men only. Eyetracking results showed that people spent more time reading morality information.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that explicit attitudes are made by propositional learning, which is the main component for evaluating others with several meaningful fragmentary information, and implicit attitudes are formed by top down process. And as well as those of previous studies, morality information was suggested as the most important factor in developing attitudes.

In recent days, thanks to the internet, people easily exposed to the information of numerous unknown others. These informationare usually fragmentary and small amount but can bemeaningful enough to evaluate others. Thereforeone develops positive or negative attitude toward them. However, evaluation can easily be biased, because of insufficient information. For example, in social dating application, people evaluate others by several brief information like appearance, personality, intellectual ability and decide to meet or not. To explain the phenomenon that people evaluate and develops attitude towards people usingseveral meaningfulpersonal informationwith small number of exposure, we performed experiments based on attitude formation theory. Also we tried to figure out what kind of personal information influences people to develop attitude using eye tracking technique.

Implicit attitudes are unconscious evaluations towards an object or the self. On the other hand,explicit attitudes are evaluations made at the conscious level.1 Both types of attitudes are predictive of behavior.2 Using a direct question like ŌĆśDo you favor~?ŌĆÖ, a person's explicit attitudes can be evaluated, but implicit ones are not easy to access because they are not conscious attitudes.

The Associative-Propositional Evaluation (APE) model3 is a theory that demonstrates the relationship between implicit and explicit attitudes. According to APE model, evaluation includes both associative and propositional processes. An associative process involves the activation of evaluative associations in reaction to a stimulus, which induces an individual's automatic affective response (implicit attitude). In a propositional process, person validates the evaluation through propositional reasoning (explicit attitude).4 In this APE framework, implicit and explicit attitudes are learned and change in different ways.4 Implicit attitude is affected by repeated pairings of positive or negative stimuli with an object, and is similar to classical conditioning.5 These pairings make object to be felt as negative or positive. Implicit attitudes are formed and change slowly.6 Explicit attitudes are related to a fast-learning system. They are affected by recent information, especially newly presented propositional information, and are related to high level cognition like inference of the relationships among given information.7 Therefore, the same learning experience can have different effects on implicit and explicit attitudes.8 Furthermore, they can affect each other during their formation.3

Many previous studies have used repetitive pairing of stimuli to induce implicit and explicit attitudes.5 They used a large number of pairs, several hundred, and succeeded in making both implicit and explicit changes in attitudes. However, we insist that small number of repetitive pairings are also able to make attitudes if information are meaningful to evaluate person. And this phenomenon frequently occurs in our daily life, especially in recent days. This type of attitude formation was not sufficiently examined in previous studies using the APE model framework. It is not clear whether both explicit and implicit attitudes are formed, and how the two types of attitudes interact during the formation. What attitudes are dominant as a result of that interaction? What information was important in forming the attitudes about a person is an interesting question.

In this study, we aimed to verify the answers to these questions by giving four meaningful and fragmentary personal information and then measuring explicit and implicit attitudes. We hypothesized that participants would form explicit attitudes with inference from some personal information about a newly introduced person, which would be strengthened by imagination and reminding, and implicit attitudes would be formed by imagination based on explicit attitudes. For behavioral measurement, eye tracker was used to verify what information was the most meaningful to participants in forming attitudes.

Thirty-three participants were recruited aging from 19 to 31 years (20 males and 13 females). All participants were recruited via a notice on an online community of KAIST and took part voluntarily providing written informed consent. Among the 33 participants, two males and two females were excluded in the analysis because of incomplete data acquisition. Among the twenty-nine subjects, eighteen were male (62.1%), and the mean age (SD) was 23.7 (3.2). This study was approved by Institute of Review Board in KAIST.

To select words which have information with similar affinity and meaningful in evaluating person, we conducted a pre-experimental survey including 180 sentences about appearance, intellectual ability, personality and morality. We chose sentences that are used frequently to explain someone in daily life. Forty-six subjects who did not participate in main experiment were included. Participants put an affinity score between ŌłÆ5 and 5 for each sentence. The mean and standard deviation of the score was 0.47 and 2.12, respectively, which was slightly positive biased. Because people showed different distributions of the affinity score, we took a z-transform of each person's score distribution and averaged them. A positive z-score indicates a positive affinity and vice versa. The standard deviation was 0.81. Then, we chose four positive sentences describing a good man and woman each and four negative sentences for a bad man and woman each. The chosen sentences had moderately deviated z-scores and the sum of the z-scores for each virtual person was chosen to be similar to each other. Mean z-scores and the original score of the information was 0.91 and 2.99 for a good man, ŌłÆ1.04 and ŌłÆ2.21 for a bad man, 0.89 and 2.81 for a good woman, and ŌłÆ1.03 and ŌłÆ2.08 for a bad woman. The chosen sentences were considered to be ŌĆśmoderatelyŌĆÖpositive or negative toward the subjects.

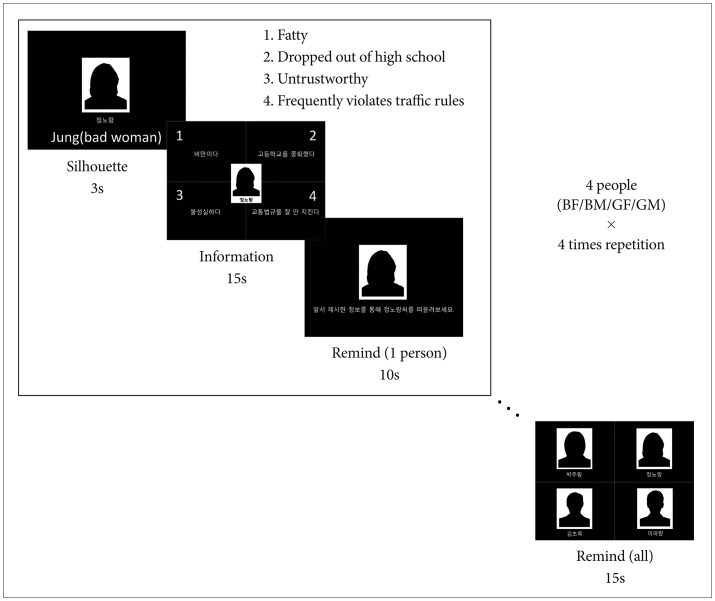

Experiment was done in two phases - attitude making and testing. In attitude making phase, silhouette of person with name was presented for 3 seconds. Then in next screen, 4 information of that person was presented in one screen for 15 seconds and eye movement was tracked to find out pattern of using each information to make attitude. After information providing screen, silhouette of person with name was re-presented and subjects were asked to imagine about that person as detailed as possible to make attitude effectively. This whole process was done for four virtual people each and repeated for four times. Finally, name and silhouette of all virtual people was presented in one screen and participants were asked to imagine about all virtual people (Figure 1). In test phase, explicit attitude was measured by explicit affinity test and behavior prediction test. Also implicit attitude towards virtual people were measured by Implicit Attitude Test (IAT).

Participants answered two post-experiment surveys for final evaluation. The first one asked them to score their preference for each virtual people, using a Likert score with a seven point scale. In the second survey, behaviors in certain situations-for example, he or she kindly got a lost boy to his destination-were given and participants checked how much the virtual person was likely to do such things. A total of six cases were given, three of them were of good actions, while the others were bad ones. A Likert score with an eleven point scale was used.

The Implicit Association Test (IAT)9 was used to detect implicit attitudes. We used freeIAT software (http://www4.ncsu.edu/~awmeade/FreeIAT/FreeIAT.htm) modifying some settings. Two sets of IAT tests, one for a virtual male, and another one for a virtual female were designed to measure the difference of implicit attitudes formation between good and bad virtual person. Test were consisted of five blocks with twenty-stimuli each. Stimuli were consisted of 16 positive or negative words (eight each), silhouette, first name and last name and of each virtual people. Stimulus were presented on center of screen and participants were asked to making judgment of stimulus category which appeared on right and left side of screen by pressing ŌĆśdŌĆÖ for left or ŌĆśkŌĆÖ for right. Only data of block 3 and 5 were analyzed, which made judgment the stimulus of combined category. For example, in block 3 (congruent block), participants decided whether freedom belongs to category 1 (good man or positive word) or category 2 (bad man or negative word). However, in block 5 (incongruent block), same stimulus was categorized to category 1 (good man or negative word) and category 2 (bad man or positive word). If a participant have positive or negative attitudes toward a virtual people, they would feel it hard to categorize the stimuli of block 5 than block 3. Therefore that difficulty of categorization would have made reaction time or error rate greater in trial 5 than trial 3. For these reasons IAT test results were scored using an improved scoring algorithm which considered the response time difference between trial 3 and 5 and the error rate difference as an index of implicit attitudes. These scores are called ŌĆśD scoreŌĆÖ and it has possible range from ŌłÆ2 to +2. Break points for ŌĆśslightŌĆÖ (0.15), ŌĆśmoderateŌĆÖ (0.35) and ŌĆśstrongŌĆÖ (0.65) were selected by previous study.10 Also we applied Student's t test to D score to determine the existence of significant implicit attitude formation.

To investigate the degree of participants' interest in each piece of information, eye movements were recorded during the information giving stage of the experiment using a SensoMotoric Instruments (SMI) REDmx Scientific eye tracker. The eye tracker recordings were taken from both the eyes of the participants' with 60 Hz frequency. The spatial accuracy of the eye tracker was better than 0.05 degrees. Participants were initially calibrated for recording eye position with the SMI eye tracker, and their eye movements were recorded until the end of the information giving session. Because the 4 information were presented in each quadrant of the screen, the total eye gaze time on each quadrant of the screen was calculated using the eye tracker, and this time was used as the information reading time (IRT). We analyzed the sums IRT of all sessions, which we called the total information reading time (TIRT), and then the IRT of each information giving session to discover varying tendencies of the IRT distribution over repetition.

To measure the effects of our paradigm on explicit affinity scores of four virtual people, we used a 2 (virtual person's positive/negative impression) by 2 (gender of virtual person) analysis of variance (ANOVA). The differences in possibility of action among four people were also evaluated using a 2 by 2 ANOVA. In addition, the relationship between the affinity score and the possibility of action was measured using a partial correlation analysis. To analyze eye tracker data, 2 (virtual person's positive/negative impression) by 2 (gender of virtual person) by 4 (information) ANOVA was used to determine the difference of TIRT and IRT of each session. Post-hoc analysis was performed with an independent two sample t test for all ANOVA results. The sex of the subjects was used as a covariate of all the analyses. All statistical tests were performed with ŌĆśR version 3.1ŌĆÖ (http://www.r-project.org/) and a significant threshold of p<0.05 was used.

Explicit attitudes were measured with changes in affinity score between before and after exposure to information about the virtual person. In the affinity score, 2-factor, 2-level ANOVA (Figure 2) showed significant main effects of both the virtual person's polarity (positive/negative) of the applied information [F (1, 111)=343.340, p<0.001] and the virtual person's sex [F (1, 111)=17.170, p<0.001]. But there was no interaction [F (1, 111)=0.424, p=0.516] between them. Positive, compared with negative, information significantly increased affinity scores in both virtual men [t (56)=13.437, p<0.001] and women [t (56)=12.780, p<0.001] in an independent two sample t test. Interestingly, the increment of affinity score elicited with positive information was significantly higher in virtual women than men [t (56)=2.833, p=0.006]. In contrast, the decrement of the affinity score by negative information was more remarkable in virtual men than women [t (56)=3.048, p=0.004].

In the survey for expectation of doing positive or negative behaviors after exposure to the four kinds of information about the virtual person (Figure 2), there were significant main effects of the polarity of the applied information on the scores of negative behavior expectation [F (1, 111)=134.465, p<0.001] and positive behavior expectation [F (1, 111)=189.699, p<0.001]. No interaction between valence and sex of the virtual person was shown in the negative behavior expectation, but marginal interaction was shown in the positive behavior expectation [F (1, 111)=3.801, p=0.054]. Similar to the affinity score, virtual people with positive information were anticipated to perform positive behavior in virtual women [t (56)=8.067, p<0.001] and men [t (56)=11.665, p<0.001] and virtual people with negative information were anticipated to perform negative behavior in virtual women [t (56)=7.355, p<0.001] and men [t (56)=8.912, p<0.001].

D score of virtual men, 0.237, was higher than the break point for slight implicit attitude formation of 0.15, but the score of women, 0.042, was not. Statistical analyses with t-test also showed significant implicit attitude formation in D score of virtual men [t (28)=3.913, p<0.001], but not in women [t (28)=0.740, p=0.465]. To verify the difference of IAT results between men and women, we compared the reaction time and error rate each. In paired t-test for evaluating the reaction time difference between block 3 and 5, the reaction time was significantly delayed in block 5 than 3 in men [t (28)=2.102, p=0.045]. However, this delay was not found in women [t (28)=0.767, p=0.449]. Error rate did not show significant difference in both virtual men [t (28)=ŌłÆ1.434, p=0.163] and women [t (28)=ŌłÆ0.166, p=0.869], which indicates that reaction time difference mainly affected the difference of D score. Although participant's sex was added as a covariate, the significant gender effect of virtual people on D score was survived [F (1, 55)=0.229, p=0.024]. But there were neither significant effect of participant's sex [F (1, 55)=5.424, p=0.634], nor interaction between gender effect of virtual people and participants [F (1, 55)=0.262, p=0.61].

Partial correlation analysis was performed to measure dependency between implicit and explicit attitudes. Because our IAT scores measure the implicit attitude difference between good and bad virtual people, the difference of affinity score between good and bad virtual people was used as an explicit attitude score. There was no significant correlation between the two scores in virtual men [r (26)=0.178, p=0.366] and women [r (26)=0.061, p=0.758].

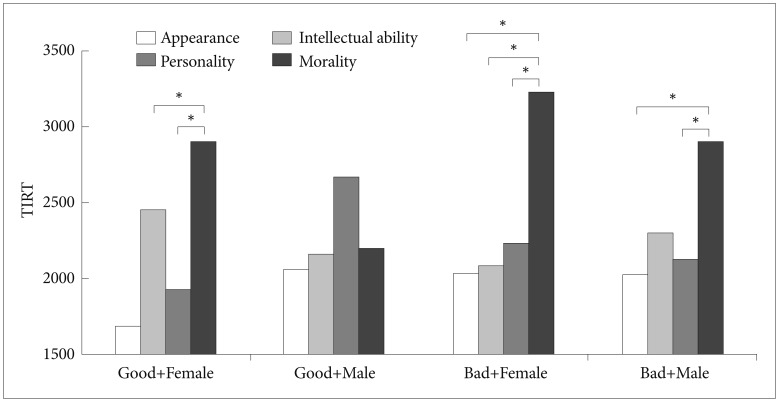

In our eye tracking data, the 2 by 2 by 4 (sex, the polarity of the applied information and aspect) ANOVA of TIRT (Figure 3) showed significant main effect of aspects [F (3, 447)=9.778, p<0.001]. And the sex of virtual people and the kind of information showed a marginal level of interaction [F (3, 447)=2.549, p=0.055]. In post-hoc analysis (Figure 3), gazing time on morality information was significantly longer than all other information in almost all virtual persons except the good man (all p<0.05) in an independent two sample t-test, except the morality of the good man and other information (p>0.05), and difference between intellectual ability and morality of the bad man [t (56)=1.290, p=0.202] and the good woman [t (56)=0.151, p=0.880]. Also, in the post-hoc analysis of interaction, significant interaction between the sex of the virtual people and the kind of information appeared in the bad man and the bad woman pair [F (3, 223)=5.188, p<0.05] and the good man and the bad woman pair [F (3, 223)=3.434, p<0.05].

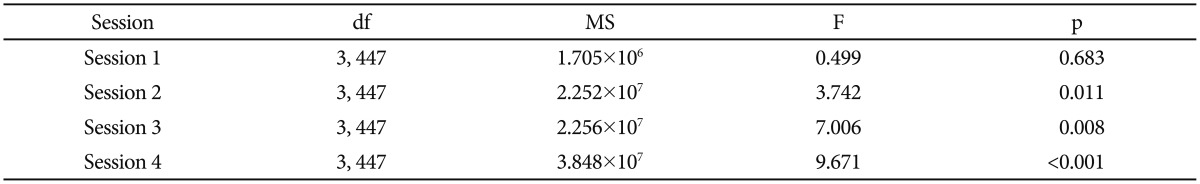

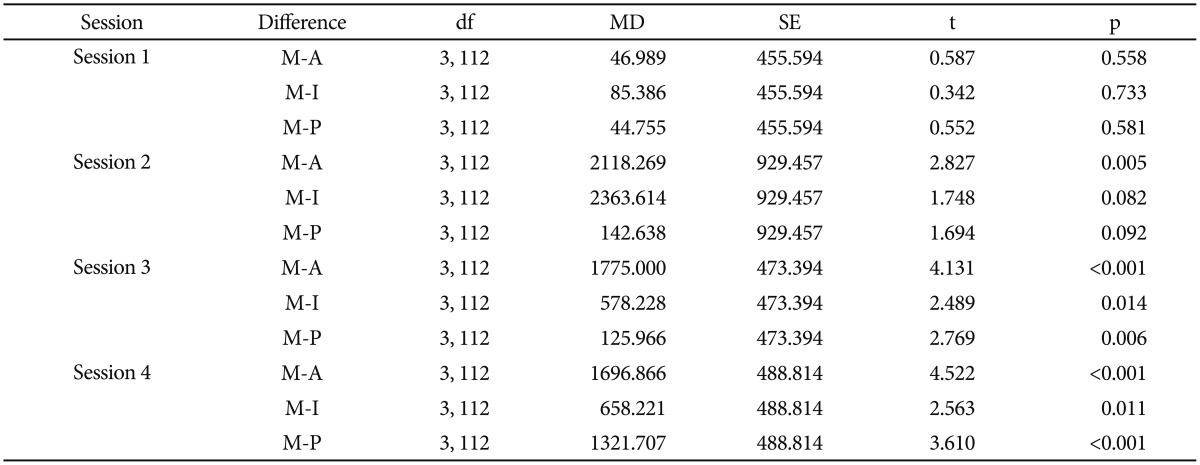

In addition, in the same design ANOVA of IRT (Figure 4) of each piece of information showed no effect of aspects in session 1 [F (3, 447)=0.499, p=0.683], but significant effect of aspects were seen in the following sessions (all p<0.05) (Table 1). Post hoc analysis using an independent t-test showed that the IRT of morality information was longer than almost all other information in sessions 2, 3, and 4 (all p<0.05, except two t-test that showed marginal level of significance) (Table 2).

In the partial correlation analysis of the eye tracker result with the explicit preference score and the Implicit Association Test (IAT), none of them showedsignificant correlation.

Our results showing a significant difference in the explicit affinity test score between good and bad and reporting the expectation of positive behavior on positive virtual people indicate that explicit attitudes about virtual people can be formed with four fragmentary pieces of information. Our eye tracker data suggested that morality is the most important type of information in forming explicit affinity about a virtual person. However, IAT results showing a weak meaningful change only in men and not in woman suggested a gender effect of the fast changes in implicit attitudes.

According to the APE model, the formation of our explicit and implicit attitudes can be explained in two ways-top down or bottom up. The first possibility is that dominant explicit attitudes influence implicit attitudes by top-down process.11 A previous study reported this kind of attitude formation, which means that a proposition regarded as valid activates associated similar mental representations and induces implicit attitudes change.12 In our experiment, information like ŌĆśFrequently violates traffic rules' which is meaningful enough to infer about person, would be evaluated using a pre-existing proposition and resulted negative explicit attitudes. In the imagination screen, mental representations associated with these negative propositions would arise in participants' minds that affect implicit and explicit attitudes formation. And repetition strengthens these processes. The second possibility is that implicit attitudes were formed by conditioning with 4 negative or positive sets of information and 4 times of repetition. It is known that a sufficient number of pairing with a strong stimulus can induce implicit attitudes13 and explicit attitudes can be derived from implicit attitudes.514 For example, 4 negative information would create a negative implicit attitude toward virtual man and this attitude would make propositions like ŌĆśI don't like him,ŌĆÖ which can appear in an explicit affinity test.

In our experimental paradigm, evidences supports top down process. In most of previous studies that showed bottom up process used large number of pairing about several hundreds. And these studies showed both strong implicit and explicit attitude514 and significant relationship between explicit and implicit tests.15 But in our implicit attitudes results, which were formed weakly only in virtual men and not in virtual woman, are not likely to make significant explicit attitudes. Also, there was no significant relationship between explicit and implicit tests. Finally, the imagination process can make or strengthen a weak implicit attitude about virtual men. Previous studies used imagination to change implicit and explicit attitudes.1617 And, in the studies of impression formation which is similar to attitude formation, showed just seeing information and active impression making with given information induces different brain responses.18 From these studies, we could infer that imagination using explicit information could make or strengthen implicit attitude differently with just perceiving information. These three pieces of evidenceattenuates the possibility of bottom up process and support the top-down hypothesis and which means propositional validation of information formed explicit attitudes and even seems to have influenced implicit attitudes.

During propositional learning, people selectively search for information that supports the validity of their proposition.19 Therefore, if some information is regarded as more important in forming explicit attitudes, people would selectively search for this information after explicit attitudes are made. Our eye tracking data of each session showed that subjects spent an equal amount of time gazing at each piece of information during the first session. However, after the first session, people spent more time on moral information than other information. We hypothesized that in first session people made explicit attitudes mostly based on moral information.Therefore, in the subsequent sessions, people spent more time looking at moral information which supports explicit attitudes toward person than other. Several studies reported that moral information is the most important one in impression formation20 and making evaluation.21 Taken together, we can infer that moral information is most meaningful one in making attitudes.

There are some limitations to our study. First, although our results showed gender effect of IAT and we verified the factors that can cause this effect, this it is hard to confirm the differential implicit attitude formation toward men and women because of small number of participants. Second, although we supported the top down process of making implicit attitude, it was hard to quantifying the effect of top down process in our experiment, because we didn't controlled the duration or number of imagination and information. Therefore, considering first and second limitation, future experiment should clarify the different implicit attitude formation by top down process toward men and women while controlling the effect of top down process by differentiating imagination condition. And this experiment should include sufficient number of subject to get enough statistical power and to see various group effect. Also, culture and ethnicity could affect the formation of attitudes. Further studies in subjects with multicultural backgrounds are needed to generalize our results.

In the past, people usually were exposed to information of limited number of people for long time. In these condition, which is similar to large number of pairing with various kind of information about a person, one could developproper implicit and explicit attitude toward person. However, people in these days are frequently exposed to short pieces of information about someone which is meaningful but superficial. Our results suggested that these short and fragmentary amounts of information with imagination can make people to form explicit attitudes and even implicit attitudes, toward the person. This means that we might like or dislike a person deep in our mind even though we know only little of him/her. This would create biased judgment about him, even in situations that are not related to the given information. We believe our study provides beneficial evidence about how attitudes are formed in current social circumstances.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant for KAIST Future Systems Healthcare Project from the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (N10150017, N01150030 to B Jeong).

References

1. Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychol Rev 1995;102:4-27. PMID: 7878162.

2. Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. J Pers Soc Psychol 2009;97:17-41. PMID: 19586237.

3. Gawronski B, Bodenhausen GV. Associative and propositional processes in evaluation: an integrative review of implicit and explicit attitude change. Psychol Bull 2006;132:692-731. PMID: 16910748.

5. Olson MA, Fazio RH. Implicit attitude formation through classical conditioning. Psychol Sci 2001;12:413-417. PMID: 11554676.

6. Rydell RJ, McConnell AR. Understanding implicit and explicit attitude change: a systems of reasoning analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 2006;91:995-1008. PMID: 17144760.

7. Fazio RH, Jackson JR, Dunton BC, Williams CJ. Variability in automatic activation as an unobtrusive measure of racial attitudes: a bona fide pipeline? J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;69:1013-1027. PMID: 8531054.

8. Moran T, Bar-Anan Y. The effect of object-valence relations on automatic evaluation. Cogn Emot 2013;27:743-752. PMID: 23072334.

9. Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1998;74:1464-1480. PMID: 9654756.

10. Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the implicit association test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. J Pers Soc Psychol 2003;85:197-216. PMID: 12916565.

11. Gawronski B, Bodenhausen GV. The Associative-Propositional Evaluation Model: Operating Principles and Operating Conditions of Evaluation. In: Sherman JW, Gawronski B, Trope Y, editor. Dual-Process Theories of the Social Mind. New York: The Guilford Press, 2014, p. 188-203.

12. Peters KR, Gawronski B. Mutual influences between the implicit and explicit self-concepts: the role of memory activation and motivated reasoning. J Exp Soc Psychol 2011;47:436-442.

13. Amodio DM. The neuroscience of prejudice and stereotyping. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014;15:670-682. PMID: 25186236.

14. De Houwer J, Thomas S, Baeyens F. Association learning of likes and dislikes: a review of 25 years of research on human evaluative conditioning. Psychol Bull 2001;127:853-869. PMID: 11726074.

15. LeBel E, Gawronski B. Reasons versus feelings: Introspection and the relation between explicit and implicit attitudes In: the 7th Annual Meeting of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology; Palm Springs, CA. 2006.

16. Turner RN, Crisp RJ. Imagining intergroup contact reduces implicit prejudice. Br J Soc Psychol 2010;49:129-142. PMID: 19302731.

17. Vezzali L, Capozza D, Giovannini D, Stathi S. Improving implicit and explicit intergroup attitudes using imagined contact: an experimental intervention with elementary school children. Group Process Intergr Relat 2011;15:203-212.

18. Mitchell JP, Macrae CN, Banaji MR. Encoding-specific effects of social cognition on the neural correlates of subsequent memory. J Neurosci 2004;24:4912-4917. PMID: 15163682.

20. Brambilla M, Sacchi S, Rusconi P, Cherubini P, Yzerbyt VY. You want to give a good impression? Be honest! Moral traits dominate group impression formation. Br J Soc Psychol 2012;51:149-166. PMID: 22435848.

Figure┬Ā1

Experimental design of making attitudes. Participants were given four kinds of information about each four virtual people and reminded about them. This process was repeated for four times. Finally, participants were asked to remind about all virtual people simultaneously in the last screen. BF: bad female, BM: bad male, GF: good female, GM: good male.

Figure┬Ā2

Changes in explicit attitudes to a virtual person. Affinity score result (left) shows a significant main effect in valence and gender of virtual people (both p<0.001). In behavior prediction results (middle and right), prediction toward virtual people varied by their valence (p<0.001) but not by gender. *p<0.05.

Figure┬Ā3

Total information reading time (TIRT) on four kinds of aspects about virtual persons, people spent most time looking at morality information except the good male. *p<0.05.

Figure┬Ā4

Information reading time (IRT) of each session, people showed a tendency to gaze at all the information evenly when they were provided information for the first time (session 1), but after the first session, the IRT of the morality information was dominant in all sessions (p<0.05 in session 2, 3, and 4).